October 21, 2019

Download as PDF

View on The New York Times

Matthew Wong, a promising self-taught painter whose vibrant landscapes, forest scenes and still lifes were just beginning to command attention and critical acclaim, died on Oct. 2 in Edmonton, Alberta. He was 35.

The New York gallery Karma, which represented him, said the cause was suicide. His mother, Monita (Cheng) Wong, said Mr. Wong was on the autism spectrum, had Tourette’s syndrome and had grappled with depression since childhood.

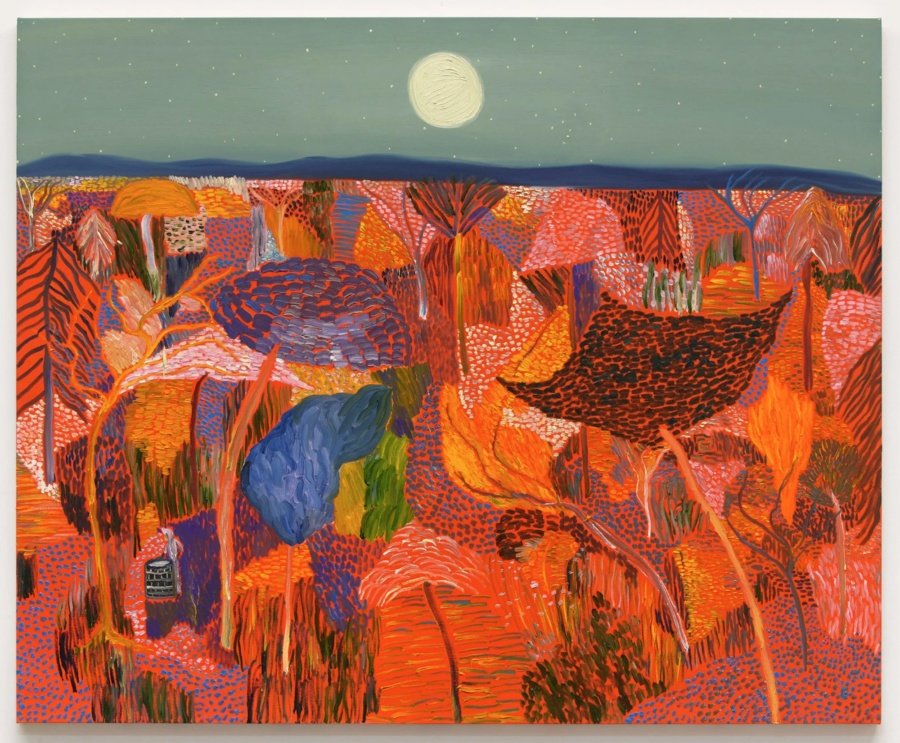

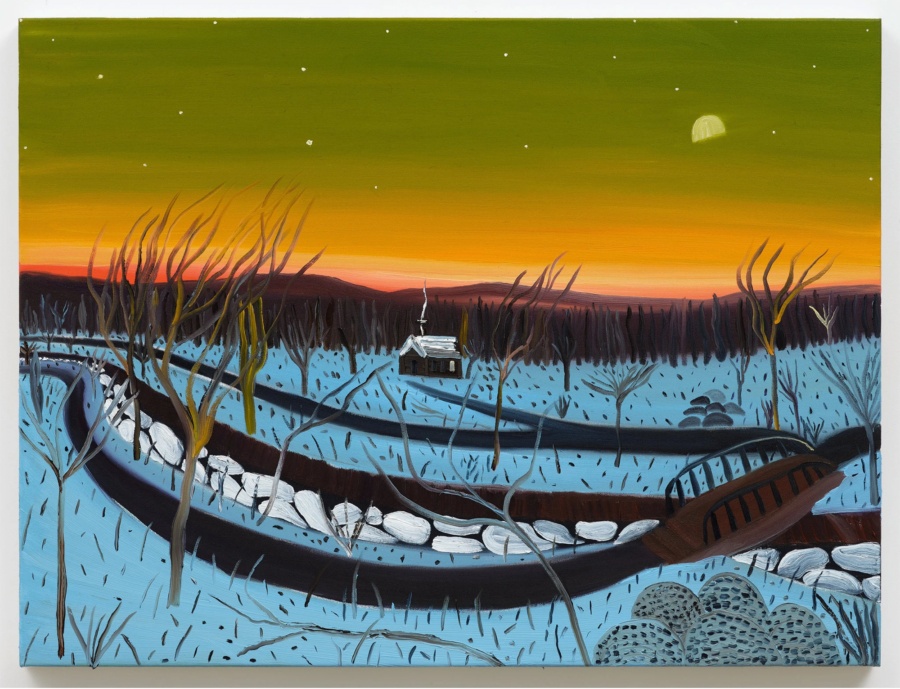

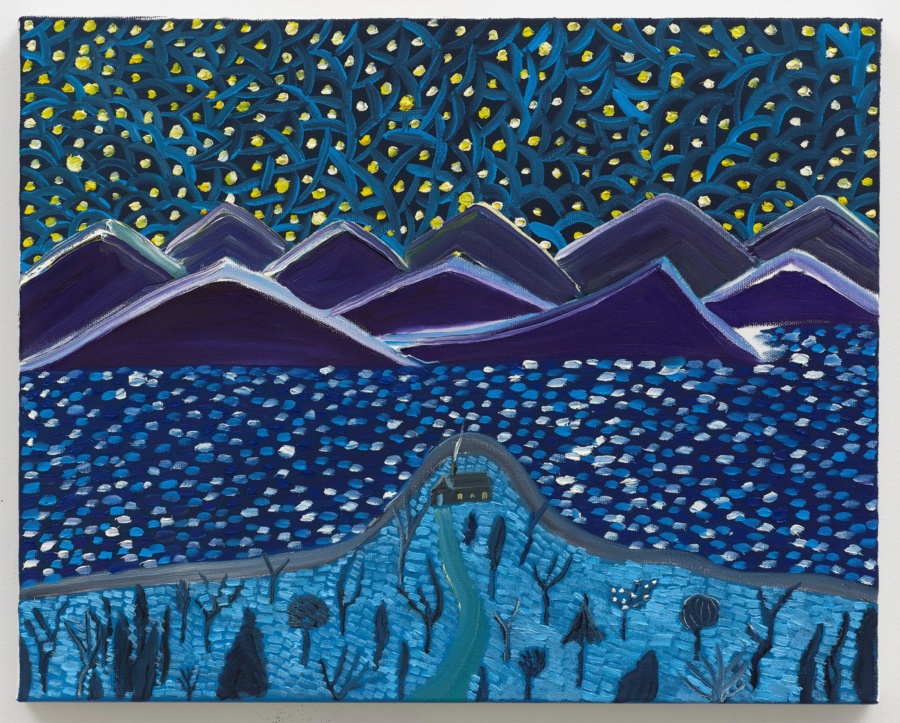

Mr. Wong’s story was unconventional, even remarkable, in the art world. He had been painting and drawing seriously only since 2013, but his striking canvases led critics to invoke Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, Milton Avery, Vincent van Gogh and other familiar painters as they assessed his work and tried to describe its visual impact. A solo show at Karma on East Second Street in Manhattan in 2018 drew raves.

“Wong can be considered a kind of nouveau Nabi,” Eric Sutphin wrote of the Karma show for the website and magazine Art in America, referring to a group of late-19th-century French artists, “a descendant of Post-Impressionist painters like Édouard Vuillard and Paul Sérusier. Like his forebears, he synthesizes stylized representations, bright colors and mystical themes to create rich, evocative scenes. His works, despite their ebullient palette, are frequently tinged with a melancholic yearning.”

His mother, in a telephone interview, spoke of his sense of isolation, and of his struggles with depression. “He would just tell me, ‘You know, Mom, my mind, I’m fighting with the Devil every single day, every waking moment of my life,’” she said.

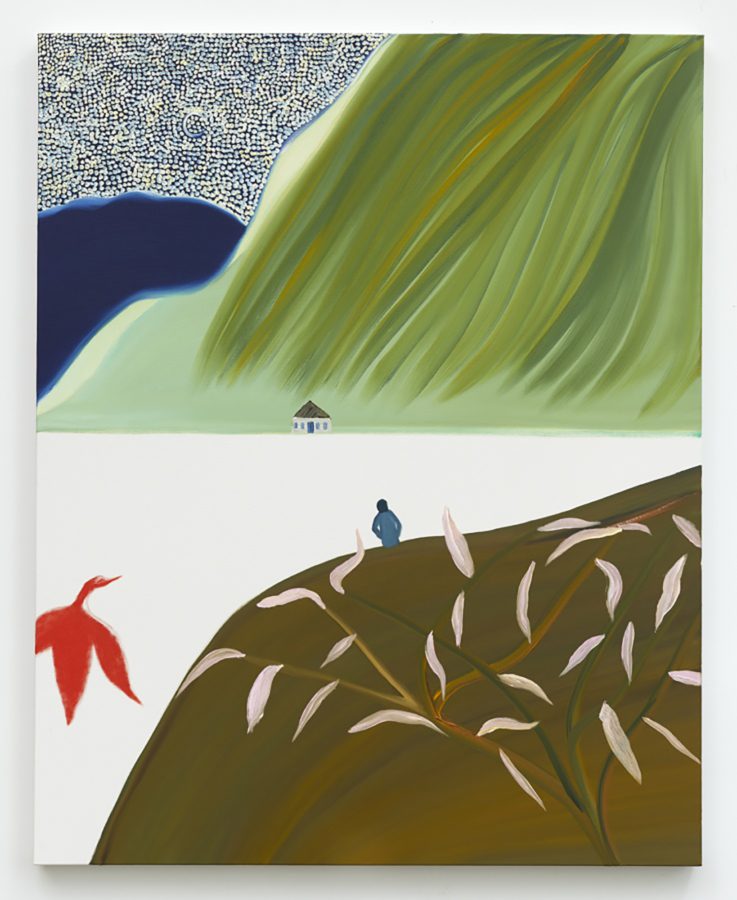

Will Heinrich, reviewing the Karma exhibition in The New York Times, commented on a singular feature of several of the landscapes in the show: a lone figure, sometimes hard to spot in a vast, vivid scene.

“At first I thought these complicated constructs of color and pattern were spoiled by the single tiny person Mr. Wong drops into most of them,” he wrote. “The figures’ rough, rudimentary drawing upsets the intoxicating ambiguity of the larger shapes like a false note, and their drastic difference in scale makes them hard to focus on.

“But in fact they’re both psychologically and formally crucial. It’s only the little gray man at a wishing well who turns ‘The Realm of Appearances’ from an exotic but contained garden into the endless expanse of the unconscious. And it’s only the sketchy gray man paddling a canoe across ‘The Beginning’ who, by keeping the painting anchored however tenuously in figuration, gives its psychedelic pointillism the power to shock.”

Mr. Wong was born on March 8, 1984, in Toronto. Ms. Wong and her husband, Raymond, both had business careers, and the family relocated to Hong Kong when Matthew was 7. When he was 15 they moved back to Toronto, in part because of his medical needs, and Mr. Wong graduated from high school there.

In 2007 he earned a bachelor’s degree in cultural anthropology at the University of Michigan, then he held several desk jobs.

“Somewhere around 2009 I took a photograph of a still life in my grandfather’s bedroom with my Nokia E87,” he told the online magazine Neoteric Art in 2014. “It was the first thing I remember doing out of my own creative volition.”

In 2010 he enrolled in the School of Creative Media at the City University of Hong Kong, receiving a master’s degree in photography there in 2013. But by then he had grown disenchanted with photography and had begun to draw.

“At first I just bought a cheap sketch pad along with a bottle of ink,” he said, “and made a mess every day in my bathroom randomly pouring ink onto pages — smashing them together — hoping something interesting was going to come out of it.”

Painting proved more fruitful, and he plunged into Facebook discussions among artists, absorbing techniques and influences, and finding other ways to educate himself.

“He would go to libraries and study all the masters — Picasso, van Gogh, Matisse,” his mother said.

He had his first breakthrough in 2015, a small solo exhibition at the Hong Kong Visual Arts Center, and images of his work online were starting to get attention. In 2016 the curator Matthew Higgs included Mr. Wong’s works in “Outside,” an exhibition for Karma in Amagansett, N.Y. It opened on Labor Day weekend, just as his mother turned 60.

“I said, ‘Matthew, this is the best birthday gift,’” Ms. Wong said.

He sold one painting there immediately, she said, and other customers began finding him.

“He was so proud of himself,” Ms. Wong said, “because he’d always been dependent on his parents.”

Though he still lived with his parents, who had moved to Edmonton in 2016, he was finding some financial stability, handling most of his growing business himself.

“I’d just help Matthew with the logistics,” Ms. Wong said, “like when he needed to ship something.”

The 2018 show at Karma was his first solo exhibition in New York.

“The reaction to his work and exhibition is something that we hadn’t experienced before with a young artist or a first show,” Brendan Dugan, the gallery owner, said by email. “It was quite astounding. And the reaction was the same from critics, colleagues and collectors.”

Mr. Wong didn’t start out selling his paintings for small amounts like some artists; Mr. Dugan said he was commanding prices in the thousands and above right off. “The highest levels of collectors were immediately interested,” he said.

Before his death, Mr. Wong had prepared a second solo show with Karma, to be titled “Blue.” It opens next month.

In addition to his mother, Mr. Wong, an only child, is survived by his father.

Ms. Wong recalled being constantly surprised at the art her son was producing in the studio he had set up in Edmonton.

“Every time I’d go to the studio with my husband to tidy up,” she said, “we’d always see something.”