December 7, 2019

Download as PDF

View on Hyperallergic

It seems that Wong was in touch with his deepest feelings and they came through in all of his art; this is what makes him special. Matthew Wong’s career was all too brief, leaving those of us who were enthralled — as I was — by his debut show at Karma (March 22-April 29, 2018) wondering what he might have accomplished had he lived longer. After all, this was the work of a self-taught painter who began painting in 2012, shortly after graduating in Hong Kong with an MFA in photography. However, not long after he completed the work that comprises his current exhibition, Matthew Wong: Blue at Karma (November 8, 2019–January 5, 2020), he committed suicide at the age of 35. Although it is hard to separate the paintings and works on paper from this overshadowing fact, I think it is important to try.

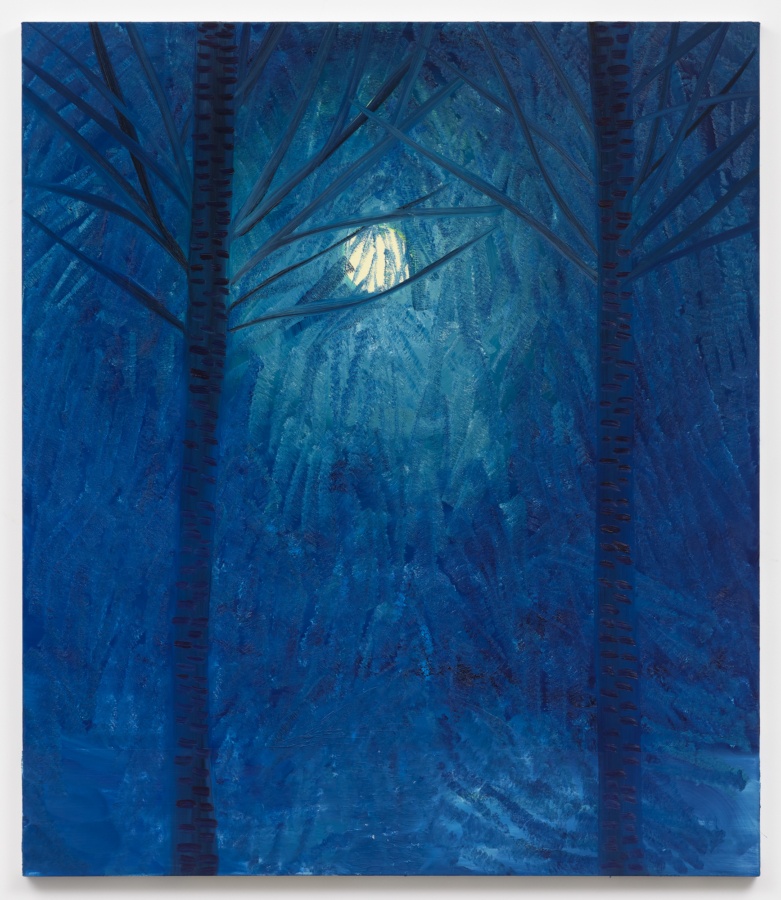

Look, the moon, 2019, oil on canvas, 70 × 60 inches

Fifteen paintings are spread throughout the two galleries, office, and front window of the large exhibition space, while eleven small works on paper, done in gouache and watercolor, are in the smaller storefront gallery a few doors away. As the exhibition title suggests, the color blue dominates almost all of the paintings and works on paper. Wong’s subjects are traditional: landscape and still life. This is how I described the paintings in his first exhibition at Karma:

Wong makes myriad lines, dots, daubs, and short, lush brushstrokes, eventually arriving at an imaginary landscape that tilts away from the picture plane at an odd angle. A painterly cartographer, Wong literally feels his way across the landscape, dot by dot, paint stroke by paint stroke.

While this method of working is true of a number of paintings, especially in the front gallery space, the paintings in the smaller back gallery show that Wong had broadened his approach to applying paint to the surface — perhaps as a result of using gouache and watercolor.

Blue Night, 2018, oil on canvas, 60 × 48 inches

In “Blue Night” (2018), which measures 60 by 48 inches, an oversized pink tulip sits in a large glass half-filled with water dotted with air bubbles. The flower and glass are in a dark blue room, sitting on a light blue surface. Behind them we see a closed door on the left and a window on the right, in the corner. Outside the window, beneath a curving band of deep blue sky, there is a tree with orange leaves, rendered with fat dots of paint. By the table on which the glass sits are the horizontal blue slats of wooden chair nearly submerged in the painting’s dark blue light.

The water glass and lone flower are too big in relation to the rest of the things in the room (the door, chair, and window). They dominate the space, demanding the viewer’s attention. At the same time, there is something tender and vulnerable about the long, thin-stemmed flower standing erect in a big glass. Is the rim of the glass holding up the flower or is it magically standing on its own? The longer we look at what might at first appear to be a simple composition the more we see.

This is what makes Wong special: it seems that he was in touch with his deepest feelings and they came through in all of his art. And feelings, as they say, can be messy. For this reason it is reductive to see his work through the single lens of his suicide. We owe Wong and his work more than that. This is why I decided not to go to any other exhibitions on the day I saw this show.

Untitled, 2019, gouache on paper, 12 × 9 inches

In “Path to the Sea” (2019), a charcoal gray path emerges from the middle of the painting’s bottom edge, rising and diminishing until it ends about three-quarters of the way up the painting’s surface. Above it is an oval — a clearing — made of three horizontal bands in various hues of blue, denoting the sky, ocean, and land. On both sides of the sinuous path Wong painted trees, leaves, foliage and fauna, using a vocabulary of full dots, dashes, and brushstroke lines. White and black paint accent the thick forest and indicate moonlight and shadows.

Wong’s works hint that he wanted a direct rapport with the viewer; often, simple gestures, as in his placement of the path, pull us into the painting and raise our attention up the painting’s surface. In fact, we might not initially notice the figure — whose head and back are seen from behind — entering into the painting from the bottom left edge. I felt a shiver of displacement pass through me as I took in the whole scene. Wong has located his viewer behind this solitary figure, who is walking through a forest at night to reach the sea. The forest is crowded with marks while the sea and sky are relatively empty, with five stars in the uppermost band. Who is this person that we seem to be walking behind and accompanying?

Path to the Sea, 2019, oil on canvas, 80 × 70 inches

In his earlier paintings Wong tended to cover the surface with myriad marks, from daubs and dashes to lines of varying lengths and widths; grouped together, they articulate a landscape made up of simple and direct paint application. There was something honest and innocent in this. The result was optical and dreamlike.

I was struck by the different techniques that distinguish these paintings from the ones Wong had shown in the same space a little more than a year ago. In “Blue Rain” (2018), he depicts a blue path leading through a field of white flowers to a house abutting a forest of tall, straight trees. Part of a vast full moon dips down into the painting’s top edge. What differentiates this from his earlier paintings is the additional layer of diagonal brushstrokes indicating rain. As in “Blue Night” and “Path to the Sea,” there is something meaningful about the incongruity. In “Blue Rain,” it seems to be raining torrentially on the night of a full moon. The moon, directly above the house, is like a beacon guiding us to shelter. The rain, however, becomes a curtain of marks separating the viewer from the house.

Blue Rain, 2018, oil on canvas, 72 × 48 inches

In “Look, the Moon” (2019), Wong waited until the oil paint was dry and sticky, rather than smooth and creamy, before applying it to the surface — instead of distinct brushstrokes and marks, the surface is textured and seems gummy. This deliberate move evokes a forest full of pine trees partly obscuring the moon, which is framed by two leafless birch trees.

In these largely unpopulated paintings, Wong invited the viewer to be a solitary observer or sojourner. He never indicated what awaits us at the end of our journey. He seamlessly integrated contradictions into his works so that they reveal themselves slowly. Wong did so much in a short period — around seven years — I don’t think a sense of loss will ever leave me when I think about him or look at his work.