December 17, 2019

Download as PDF

View on Hyperallergic

A rising art-world star, Wong planned his exhibition Blue before his suicide in October. The show reveals a marked tension between beauty and melancholy, making it difficult at times to keep his biography and work separate.

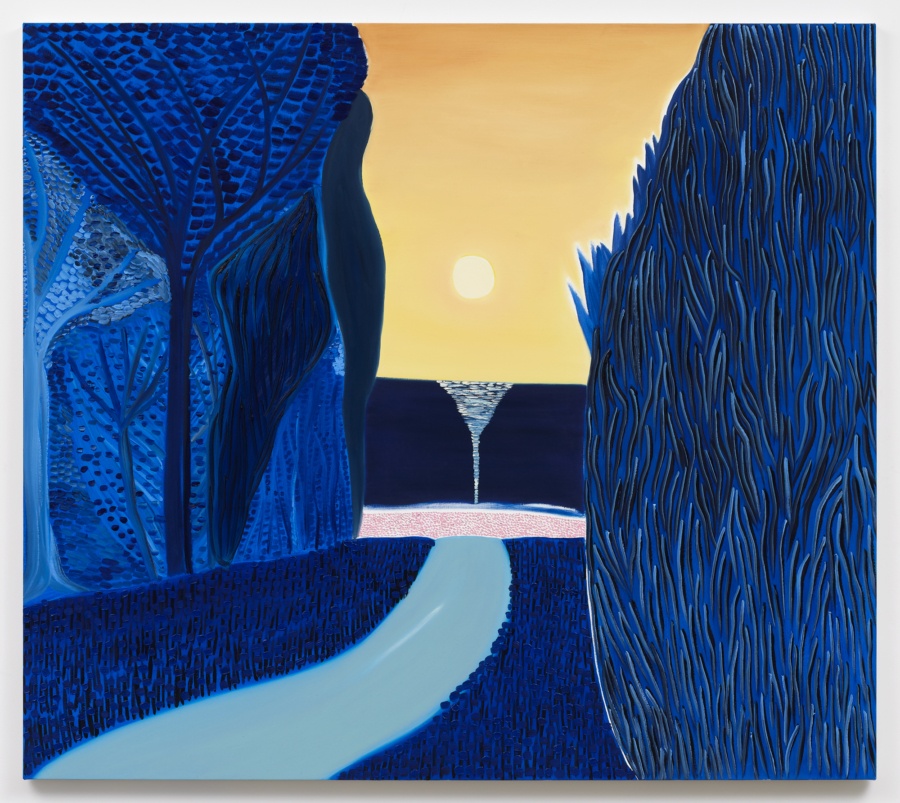

A Dream, 2019, oil on canvas, 70 × 80 inches

Artist Matthew Wong planned his exhibition at Karma Gallery, Blue, before his suicide in October of this year. The show is therefore not structured to memorialize Wong’s career posthumously; rather it simply fulfills the artist’s intention to exhibit this body of work. Wong was a rising art-world star, a rare example of a self-taught artist who was on the path to mainstream, gallery-backed success. His style has been compared to the Post-Impressionists, the Nabis, and the Fauvists, his sincerity of engagement with these eras of painting a rarity among his contemporaries.

Blue contains two distinct bodies of work: oil on canvas and gouache on paper. The gouache works are small, not much larger than a standard letter size. The oil on canvas paintings are generally around five times as large. While both explore the exhibition’s titular color, their size and materials render them quite differently. In the small works blue appears intimate, the color of dreams and private spaces. In the larger canvases blue is a color for dramatic landscapes, illusions of depth, mystery, and melancholy.

Unknown Pleasures, 2019, oil on canvas, 65 × 65 inches

The color blue has a particular hold on the human imagination. The ocean and the sky, two essential, anchoring forces in our natural world, are blue. In sociological surveys, it’s the most common favorite color. Unsurprisingly, blue has been explored in various artistic media: Yves Klein’s “International Klein Blue”; Abdellatif Kechiche’s film Blue Is the Warmest Colour; “The Blue Danube” waltz by Johann Strauss II. This list could continue; Wong was merely the latest artist to be entranced by the color’s potential.

In Blue, Wong’s work is strongest when exploring depth. “Blue View” (2019, oil on canvas) uses extremely subtle shading of a baby blue hue to give an almost monochromatic canvas the suggestion of the view out of a window onto the sky above, very delicately punctuated with four tiny dots that suggest stars. In “A Dream” (2019, oil on canvas), forests on both sides part to reveal a river that abruptly ends at the edge of daylight—a surreal scene in which Wong’s use of depth enables him to suggest the passage of time and the surreal logic of the dream world.

Blue View, 2019, oil on canvas, 40 × 30 inches

There is a marked tension in Wong’s style between beauty and melancholy. In a New York Times review of the artist’s 2018 show at Karma, Will Heinreich noted that the inclusion of small human figures often adds a psychological dimension to the work:

It’s only the little gray man at a wishing well who turns ‘The Realm of Appearances’ from an exotic but contained garden into the endless expanse of the unconscious. And it’s only the sketchy gray man paddling a canoe across ‘The Beginning’ who, by keeping the painting anchored however tenuously in figuration, gives its psychedelic pointillism the power to shock.

Melancholy is the most pronounced psychology in Blue, perhaps because of the colloquial meaning of the title, Wong’s recent suicide, and the subsequent press coverage which described his lifelong struggle with depression. Yet Karma is careful not to inject additional pathos into this exhibition’s presentation; the press release mentions Wong’s death only at the end. However, as a viewer it’s hard to keep the artist’s biography and work separate. This is particularly true of the small gouache works, which lack the drama of the larger canvases and feel more sadly intimate: moonlight shining onto an empty bed seems to suggest absence after death; a curtain blowing to the side evokes a spirit passing; even icebergs, floating in a serene sea, project an icy loneliness.

Because of this unavoidable cloud of melancholy, it will be important for Wong’s legacy that a more complete survey of his work is mounted, as soon as possible. The “blue” works should be shown in the broader context of Wong’s more vibrant, optimistic oeuvre to avoid his legacy being inextricably, limitingly linked with themes of depression and loneliness.