December 1, 2020

Download as PDF

View on Artforum

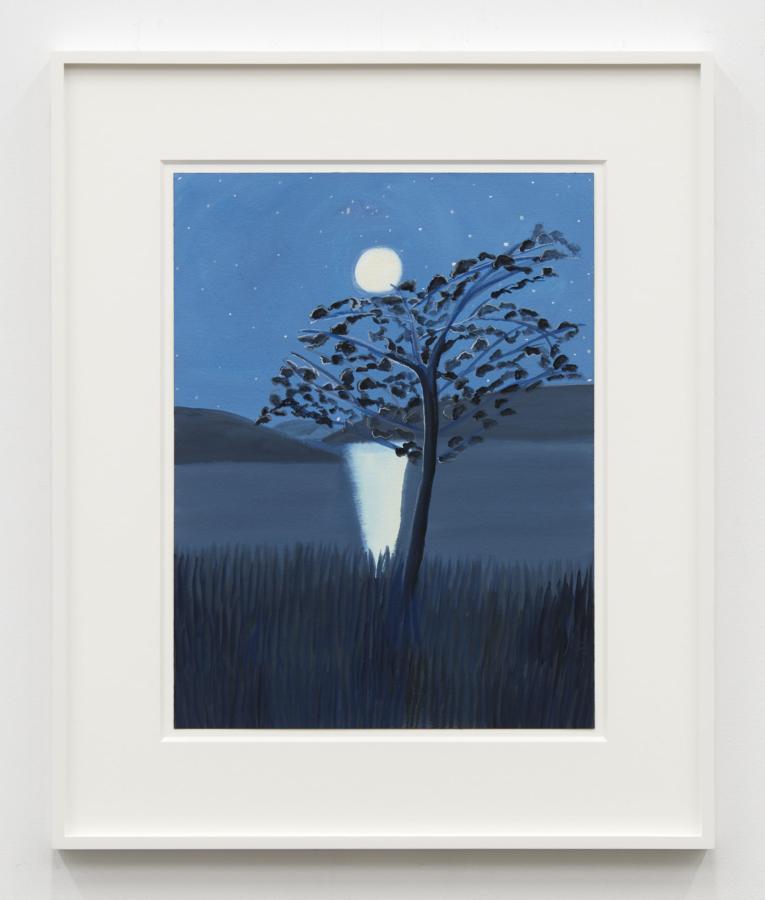

Matthew Wong, Stargazer, 2019, gouache on paper, 16 × 12 1⁄8 inches

A postcard is an ephemeral missive bearing a single image signifying a locale and a brief message, if only the classic “Wish you were here.” Very often arriving in the recipient’s mailbox after the traveler has returned, these epistles pass through space and time to become anachronistic apparitions—delayed shadows of momentary presences. For Matthew Wong’s show “Postcards,” twenty smallish watercolors were dispatched in lieu of the artist, who had been expected in Athens for a spring residency at Arch before his sudden death at the age of thirty-five. All produced last year with what now seems fervent urgency, at the rate of more than two per day, they resonate with melancholic tenderness and humor. Employing bold strokes of color as swaths of emotion anchored by the sparest of details, Wong created visual poems that are salves for the solitary soul.

Plotting a radiant trajectory across the white walls of the space, these pictures read like pages of a diary. To see them properly required getting up so close that you were engulfed in the vast scenes unfolding within their compact frames. Wong deftly evokes the subjectivity of color, speaks to seeing as feeling, employs universal archetypes, and appropriates art-historical styles and compositional devices as visual shorthand. A Voyage on the North Sea (all works 2019) shows a sailboat drifting among livid streaks of sunset red, twilight blue, and earthy umber with no horizon, the distinction between land and sky obscured. Capturing the majesty of a Romantic painting in the lurid palette of Edvard Munch, it conveys the ecstatic terror of being buffeted at the brink of corporeal and metaphysical realms.

Wong depicts ineffable states of being as much as hypothetical loci. In Reflection, a lone umbrella and empty chair face the sea beyond a fence whose stakes divide the beach and resemble the stitches of a flesh wound, recalling the stigmata of Christ. The gloaming is rendered in an ominously opaque yellow sky, reflected in the glow of an oculus beckoning in the sand like an existential escape portal. Genius, too, is a mark of difference, an illumination that teeters at the knife’s edge between stigma and singularity, alone and lonely. When you rise too high, uncomfortably close to the sky, you may long to fall back down to the familiar place where you were before you ascended. Isolation intensifies in a savage cycle of healing and fear, wholeness and dismemberment.

A Tree’s Rhythm puts the viewer amid a dazzling dance of quivering silvery branches and flickering leaves in harmony with the tempo of the cosmos. Time collapses and expands, marked in repetitive scores on the trunk very like sound notations, connecting everything in a process of continual renewal. Nature is the chief protagonist in Wong’s narratives, and elements of the landscape are uncommonly animated. Trees often bowing and nearly bereft of leaves, appearing as if from a van Gogh dream, seem to express emotions. Human figures, most often solitary and spectral, are dwarfed by the environment, merely afterthoughts—or simply fleeting.

The world looks different each and every day to the same pair of eyes; we are affected to such a degree by the sensate stimuli from our surroundings, along with the associations of past traumas and joys. In Autumn Wind, a woman gazes toward a village scintillating idyllically from a verdant hill in the distance, her gossamer scarf held aloft by the breeze. The darkly incandescent palette and lush succulent snuggling a sinuous pair of trees, intertwined like lovers, suggest Gauguin’s oneiric tropics. Yet the enigmatic blonde is straight out of Hopper. We share her perspective but can only speculate on her thoughts. The lines of a poem by Wong come to mind: “I am the wind’s last legs at dusk. I am six feet short of the moon.” Oh, that we might all leave behind traces that shine so brightly.