August 24, 2021

Download as PDF

View on The Free Press

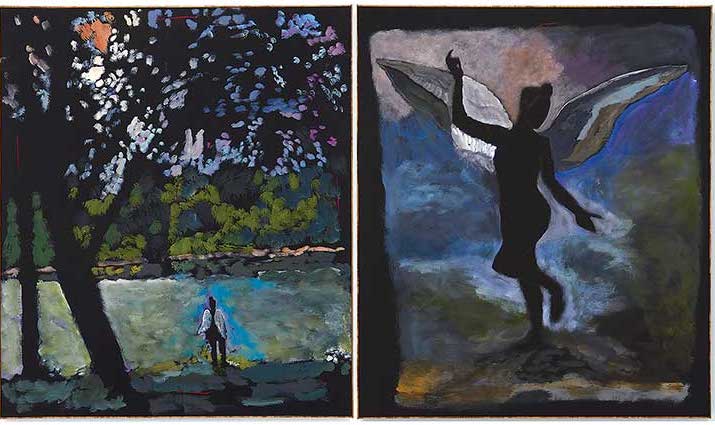

At left, “Luty,” and at right, “Ash,” both 2021, by Reggie Burrows Hodges

In Craven’s new “church” gallery, her glowing, hopeful, life-affirming paintings are joined by paintings of angels by fellow Maine-based (Lewiston) artist Reggie Burrows Hodges. The figures, anonymous in their black bodies and silhouetted profiles, emerge from different backgrounds. They exist in varying or simply open-ended regions of location and size, abstraction and representation, race and gender. One angel, Luty, is small, set along a riverbank with a large tree screening a dusky pink moon. The figure, discrete wings notwithstanding, could be anyone, incidental to a setting where any of us might find an angel on a warm summer evening, surveying a gently flowing river. Hodges’ contemplative “Luty” seems a tip of the artist’s hat to Craven’s adjacent river-washed moon paintings.

Others, though, present over life-size figures carved from indeterminate depths. The artist is reluctant to talk about where these angels come from; their familiar first-name titles suggest family or friends. But Hodges’ angels’ identities are private, hidden, disguised — and universal. They silently emerge from places we will never know. Black Angels with white wings are metaphorically charged — the power of a cliché is that it is often deeply meaningful and revelatory. Here, just when they are most needed, angels rise up from fraught times in America. There is a heaviness and sense of exhaustion among several but also absolute bravery. It takes guts and passion to paint angels in a world where too many already exist — 600,000 and counting during the current pandemic — more than were lost on both sides of the Civil War.

Other angels by Hodges are buoyant, joyful, dancing in the dark with a lightness to lift heavy hearts. For these reasons alone, the presence of Hodges’ Angels strike us as miraculous. If there are Black Angels among us, we can only hope and imagine that they beckon, guard and reside within us, that they are our own better angels, too. Darkness can be a form of light in artworks so exquisitely expressive, where the touch of a talented artist’s hand seen in soft, rhythmic brushstrokes reminds us of his and our continuing presence in the world after an immensely dark, enervating and dangerous past few years.

Hodges does allow that his angels are, in part, meant to be guardians. They bear witness to a fraught culture defined by what the artist calls our social determinants — health care, the environment, gender and racial equity, and safety, among so much else. In an uncanny alignment of the stars, Hodges’ paintings echo and expand upon many of the themes found in the work of an earlier African-American master, Bob Thompson, whose paintings are currently featured in a major retrospective exhibition at the Colby College Museum of Art in Waterville. Like Thompson, Hodges repurposes Modernism’s emphasis on abstraction — outline, shape, color and painterly gesture — into narratives of deeply personal expressiveness. His softly laid down figures and subtly blurred edges speak volumes about the technical processes and age-old traditions of painting from Rembrandt to de Kooning. But these paintings are also undeniably rooted in personal experience — from his youth growing up in Compton, California, to personal touchstones found in a heritage of African and African-American art; to the canon of Western art history (including angels); to a rising awareness that Black lives include Black artists who matter very much and who are responsible for much of the most inventive, provocative and important work being produced today. Hodges’ process begins with laying down a ground of black paint that underlies his deep, rich colors and ambiguous, weighty forms. His black ground, the very under-painting with which he shapes each angel, is the literal and metaphoric ground for images that are hearts-on-sleeves sincere, authentic and profoundly moving.

“Moons and Angels” is on view and open to the public at Craven’s gallery, 70 Main Street (next the Thomaston Academy building on Route 1), Thomaston, Saturdays and Sundays, 1 to 6 p.m., through September 19. All images are copyrighted by the artists, courtesy of Karma Gallery, in New York City, karmakarma.org. Email info@karmakarma.org, or call (212) 390-8290.