January 2008

Download as PDF

View on Artforum

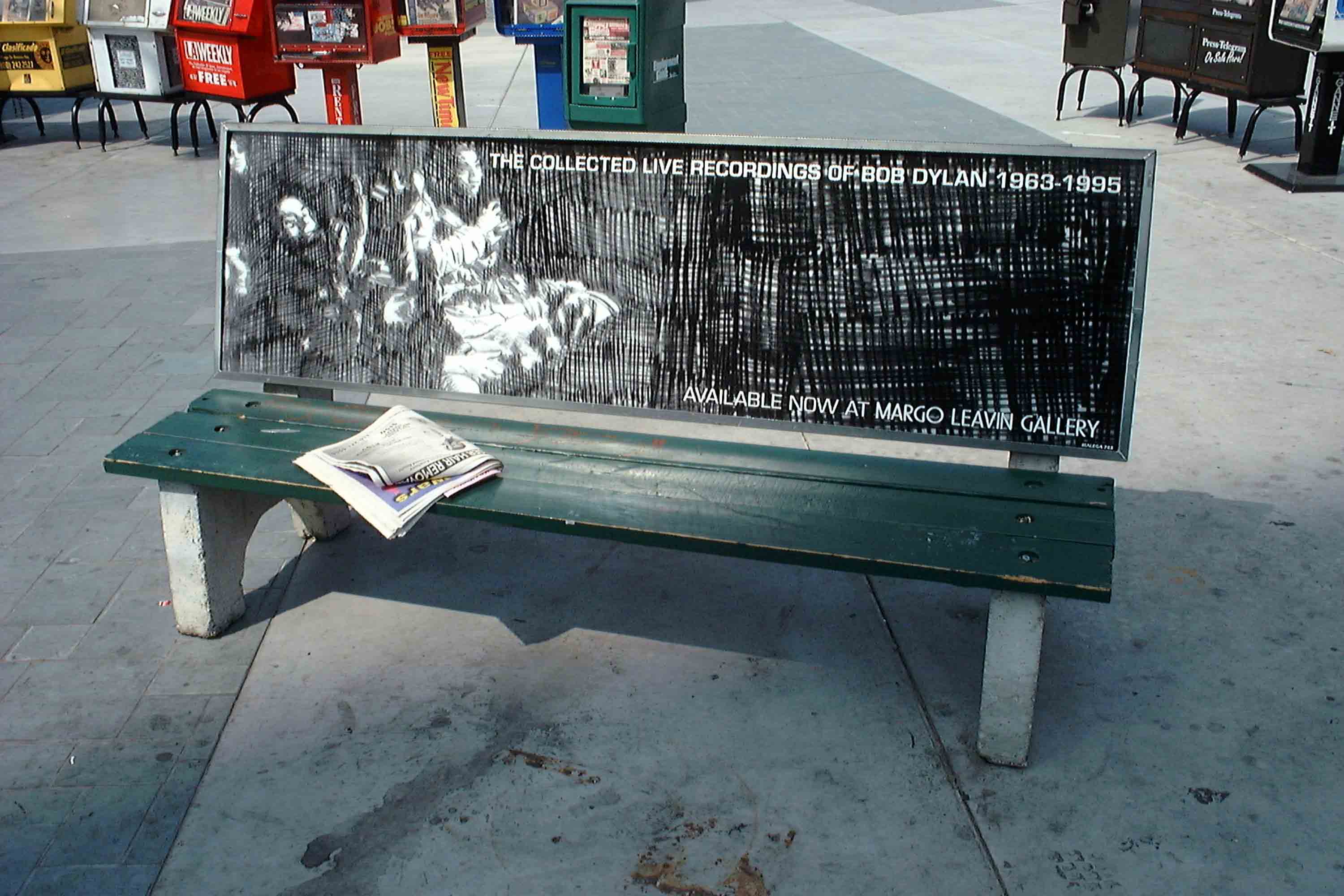

Mungo Thomson, The Collected Live Recordings of Bob Dylan, 1963-1995 (Promotional Bus Bench), 2000.

In that spirit, here is a provisional thesis on the disc from this critic: Thirty-two years of Dylan concerts without Dylan make for a contextual chronicle of ill-fated counterculture. In ’63 the singer was a threat, banned from singing “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues” on The Ed Sullivan Show. In ’66 he notoriously alienated a Manchester, UK, audience by swerving from civil rights folk to amped-up surrealistic rock. In the ’70s he became a stadium act, surrounded by foot-stomping concertgoers bellowing for “Lay, Lady, Lay.” And by ’95 he was croaking affably to Boomers on MTV. Meanwhile, the counterculture exploded, imploded, and turned into spectacle.

But if what I hear is such a downward historical drift, others have responded entirely differently to these massed noisemakers. In fact, according to the Los Angeles– and Berlin-based Thomson, some people have found the Dylan record entirely uplifting: The singer’s fans, they decide, are applauding them. Other issues nestle in there for contemplation as well—from technical ones (improved recording techniques) to ethical ones (the artist’s responsibility to his audience)—all filtering into, and spiking, the dreamy mood Thomson engineers by emphasizing the negative space around the cultural icon.

When The Collected Live Recordings was playing in an exhibition at Margo Leavin Gallery in Los Angeles in 2000, Thomson also displayed a number of wind chimes in the space. Such a juxtaposition might well make the record’s pseudo-oceanic crowd sounds whisper of how dammed-up hippie hopes were diverted into New Age’s solipsistic tributaries, but even by itself, the installation Wind Chimes, 1999, suggests countercultural entropy, offering, in the context of Thomson’s practice, a visual shorthand for the sedate mysticism that bloomed in the early ’70s. Again, though, the work is multivalent: Thomson additionally describes it as “a slightly hostile gesture towards art collectors and the acquisition of objects for the bourgeois home, [and] also engaged in a kind of endgame dialogue with modernist mobile sculpture.” Perhaps the most telling feature of these chimes is, however, that they require the shifting air currents occasioned by gallery visitors in order to “perform” and thus engage the surrounding space. (A related, forthcoming piece extends the conceit: Coat Check Chimes, 2008, will be installed in the cloakroom during this year’s Whitney Biennial in New York and will consist of specially fabricated coat hangers—essentially, tuned art, in other words, actually needs people in order to be completed.

This is a central attribute of Thomson’s broader interest in privileging access, in disseminating an open-ended, chancy art about an expanding sense of context, in expanding contexts—specifically, through artworks that both move into public arenas and put democratic spins on high-art reference points. Formats have included radio broadcasts and advertisements (the Dylan CD went on heavy rotation on Los Angeles’s alternative stations and was advertised on bus benches around the city), not to mention bumper stickers (The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths [12-Step], 1999, recasts Bruce Nauman’s ambivalent axiom as a recovery mantra). In a comically literal take on the theme of expansion, he has also turned to inflatable bounce houses: John Connelly Presents 2002–2005, 2005, for instance, replicates the former exhibition space of Thomson’s New York gallery. And, not least, he has produced a number of publications: Everything Has Been Recorded, 2000, a free comic book that the artist left in airports, phone booths, etc., sets his gradschool journal entries to an apocalyptic visual narrative, aping the format of Jack Chick’s proselytizing religious tracts; the Easy Field Guide to Mungo Thomson, 2004, authored in deadpan, Information Man–style by curator Matthew Higgs, mimics a spotter’s guide; and, most recently, Negative Space, 2006, presents color-reversed outer-space photographs culled from NASA’s public-domain online archive and wrapped in a loosely National Geographic–style cover, which has given Thomson more legal headaches than any other of his cultural borrowings.

This last work—images from which have also been made into a series of large-scale photographs—is a good example of Thomson’s generative approach to content.

Reversing colors with one quick keystroke, he transforms outer space into delicately veined marble; stars become inky pinpricks in a milky void. These photographs make me claustrophobic. It is as if “ice-nine”—the fictional substance in Kurt Vonnegut’s 1959 novel Cat’s Cradle, which catastrophically freezes anything that it touches containing water—had snap-frozen the cosmos. For his part, however, Thomson finds the photographs airy. Again, here are vagaries of reception, the lifeblood of his art, at work. But Negative Space also reveals another fundamental aspect of Thomson’s practice: his holistic dialogue with the recent history of West Coast art and culture. The book and its imagery evince the crossbreeding of northern California’s psychedelia with the dreamy haze nurtured by Southern California’s Light and Space artists. Indeed, Thomson’s entire oeuvre is inextricable from a Golden State context. With its consistent sly humor and dual interest in tranced-out states and worldly criticality, his practice is in the tradition of, and a commentary on, a number of specifically Californian rejoinders to the prevailing aesthetic dialogue in New York, from the refashioning of Minimalist art into the metaphysical airiness of Light and Space to the phasing of Conceptual art into wry, warm-blooded practices like those of Ed Ruscha, Allen Ruppersberg, and John Baldessari. (Thomson, who studied under the last at UCLA, paid tribute with Antenna Baldessari, 2002, in which the artist’s visage is transformed into a moonfaced, Santa-ish cartoon printed on those foam balls that blunt the tips of car antennae.)

Not that Thomson is nostalgic. He evidently takes California’s relaxed artistic tradition as his birthright, but, as befits someone who has also spent plenty of time in New York and lives part-time in Europe, he also has some critical distance from it. There is surely some good-natured gibing in the way he takes artistic approaches that have always been, for better or worse, peripheral, and uses them as the basis for a consideration not only of the peripheral social contexts that border them but also of the benefits of operating at a remove, the better to gain a realistic vantage point on how art might function. Thomson’s relationship to the Light and Space artists in particular is affectionate but also antagonistic: Skyspace Bouncehouse, 2007, for example, gives the inflatable treatment to a James Turrell Skyspace. For Thomson, the Achilles’ heel of Light and Space—and, casting the net wider, of metaphysical notions of withdrawal from the world—is the desire to suspend audiences at the moment of raw perception, foreclosing messy reality. Thomson doesn’t believe this to be possible, nor does he wish for it. He is, after all, a pragmatist, so, while contriving semihypnotic states, he ensures that contiguous material aplenty comes pouring in. The traditions that filtered into California mysticism from the Far East call this the “interconnectedness of all things”; Thomson’s take on it is that when you look at something long and slow, everything turns out to be in something else’s pocket, and even the most innocent subjects have sociopolitical ramifications. Everything is connected in his work, just not necessarily in some benign, oneness-like way: Again, it’s you, the freewheeling—or at least free-associating—viewer, who draws the map of precisely how.

A case in point is The American Desert (for Chuck Jones), 2002. Probably Thomson’s best-known work, this thirty-four-minute video takes an archival but destabilizing approach to every Road Runner cartoon that Warner Bros. director Chuck Jones ever made. Digitally erasing the barreling bird and the relentless Wile E. Coyote to leave only the desert backdrops, Thomson once more excludes the charismatic logotypes at the center of the action, leaving the screen an ostensibly narrative-free wall of dancing color, silent but for the occasional roar of a train or the tinkle of pebbles after, presumably, an invisible Wile E. has slammed into the base of a gorge. On some primal level, this scene—with its absent narrative that cannot be entirely effaced—calms, delights, and calls up memories of sunlit romper rooms of yore.

But flickering at this bright and nostalgic fantasia’s edges are unquiet reminders of the real. You see the depopulated desert, a column of smoke billowing upward, train tracks and endless roads, and you think, perhaps, of Los Alamos, of the conquered West, of manifest destiny. When the dunes appear, you may recall—as Rachel Kushner did when writing about Thomson’s work for the catalogue to his show at the 2004 Cuenca Biennial—that the Warner Bros. desert isn’t modeled on a real place. It is, rather, a falsifying and romantic composite of deserts in California, Arizona, and Utah (you won’t find saguaros near Monument Valley’s rock formations) that mirrors the equally fictional milieu of John Ford’s iconic westerns. Now, noting that The American Desert feels something like a moving landscape painting, think of American art during the time in which the animations were made: 1949–64. Not only was this a period bookended by Abstract Expressionism and Pop, but these years were formative for a younger generation of artists, including Michael Heizer and Robert Smithson, who felt that in order to be a groundbreaking American artist one should strike out for parched peripheries. To what extent, Thomson speculated in conversation with Kushner, were these artists shaped by Jones and his seductive Saturday-morning falsehoods? One could go on. (And Thomson has indeed gone on, with Sentences on Conceptual Art, 2003. For this gentle skit on Sol LeWitt, which piles up layers of reflexivity by also alluding to Baldessari’s 1972 video Baldessari Sings LeWitt, he copied, by hand, a list of Jones’s rules for the Road Runner cartoons, including rule four: NO DIALOGUE EVER, EXCEPT “BEEP-BEEP!”) Near the heart of the matter, though, would seem to be this: As an adult, privy to contextual facts that undercut innocent pleasures, you can’t really go home again.

This faintly melancholy tenor likewise inflects the 35-mm-film-to-video-transfer The Swordsman, 2004. In this minute-long loop, Hollywood stuntman Bob Anderson repeatedly throws a prop sword out of shot, as if to a swash-buckling hero. The work is certainly meditative, but fringing this strange, ambiguous shift in attention toward cinema’s own periphery is a lot of background material, partly predicated on the fact that Anderson, a master of his craft, threatens to be made extinct by the predations of CGI. And, if you want to scale up rapidly, the work can claim the whole of cinema—which is, after all, founded upon deceiving the audience—for its orbit. But what is also notable about The Swordsman is that if you pitched it to someone, he or she would never believe it could do everything it seems to. Given its simplicity, it shouldn’t be able to broach those obscurely saddened territories. It thus once more points to that keynote of Thomson’s art: You have to be there.

A fascinating elaboration on this idea is at the center of Thomson’s Silent Film of a Tree Falling in the Forest, 2005–2006. For this work, the artist made six one-minute studies of spruce trees falling in a forest in Alberta, Canada, which he separated with lengths of blank leader film that complicate any implicit figure/ground structure—especially given that Thomson credits Nam June Paik’s emptiness-as-potential-form riff Zen for Film, 1964, a half hour of leader, as an inspiration. The falling-tree footage is lulling, but the tranquil space the piece creates is nevertheless unstable. It calms, then creates bristling anxieties, calms again, and then makes you anxious again. Not only does the technologically muted film fail to “solve” the famous koan its title references (plus people are around, although hidden from view, cutting down the trees and operating deforesting machinery), but the last tree is blatantly felled, with a feller buncher—after which the film starts afresh. Part of the edginess here is in how the tree shifts between being a living, breathing, dying thing and a quasi-Platonic Everytree—an oscillation between specificity and symbol that Thomson repeatedly pulls off in his work, and one that is fundamental to its effect.

But the question, What does it mean? doesn’t arise—or, if it does, it is going to bounce. The potency of Thomson’s art, as Silent Film in particular makes clear, comes from its modeling of a predominantly Conceptual practice that admits the heretical possibility of loss of control, and even makes it inevitable. The apodictic approach, Thomson suggests, has run its course; indeed, it was perhaps always unrealistic, given our associative and willful minds. Thomson argues instead for an art more attuned to human psychology, one focused on the strategic construction of opportunities for encounters, ripe with inference but allergic to didacticism—and, consequently, one that opens up spacious unexplored territories for cognition. On The Collected Live Recordings, there’s a line Dylan doesn’t get to sing from a stage in Manchester in 1966: “You’re right from your side / I’m right from mine.” But he doesn’t need to, because Mungo Thomson keeps on singing it for him.