May 11, 2020

Download as PDF

View on T Magazine, The New York Times

The sumptuous craft was introduced along the country’s trade routes centuries ago. Even now, links to this delicate tradition still remain.

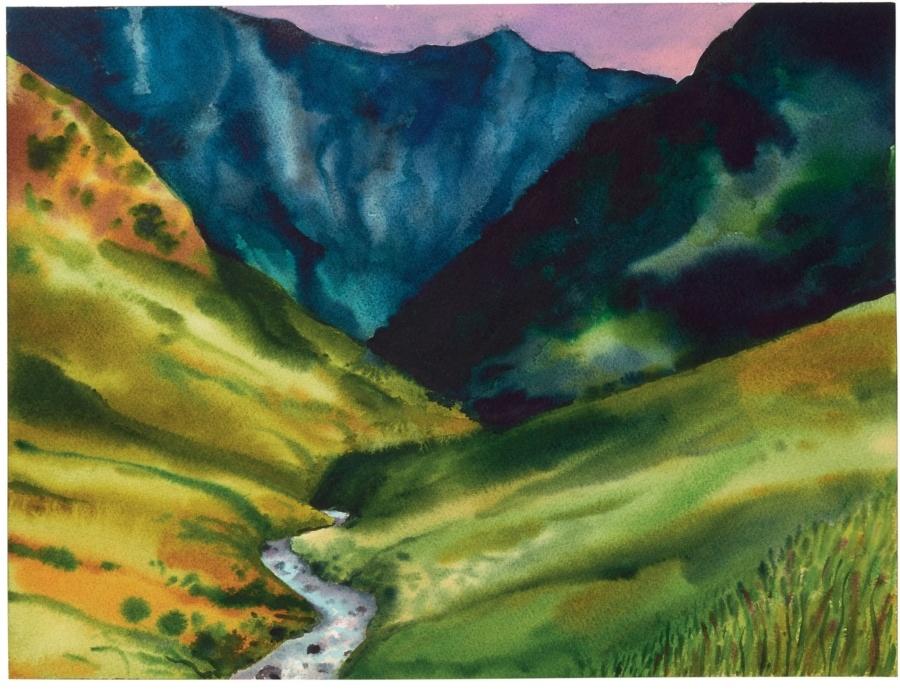

The New York-and Brussels-based Swiss artist Nicolas Party created these paintings inspired by the Georgian landscape and art of silk-making exclusively for T. Here, a river runs through the verdant Greater Caucasus Mountains. Artwork by Nicolas Party. Photo by Weichia Huang

1. TBILISI RISES OUT of the steep banks of the Mtkvari, in Georgia, spread wide on either side of the river like hands cupping a bowl — a city of cobblestones, winding lanes and wrought-iron gates bleeding rust. It is filled with the particular decay of the old Soviet republics, and the air smells of fresh bread, hot herb soup and scorched motor oil.

I arrived on a winter’s night in January. Dusk was just coming on, and the buildings were startlingly bright in the wet streets, darkness eating their edges. I’d come to Georgia to explore not just what the country has become but also its various pasts. I’d come to see its grand Orthodox churches, erected from the fourth century, when Christianity was officially adopted by these lands; I’d come to visit the silk museum in the heart of Tbilisi, a place that since the 19th century has fought for the survival of silkworms and sericulture. I’d come, ultimately, to speak to the Georgians who worked fiercely to preserve their nation’s ancient silk-making traditions, those for whom its loss meant the death not just of an art but of an entire way of life.

The collective stories we tell about who we are as nations are rarely straightforward. Even the origins of a country’s name can be a matter of dispute. Georgia has been called Georgia since as far back as the eighth century B.C. — but I discovered three different myths as to how that name came to pass: One says that it was named in honor of St. George, the country’s patron saint who was killed under the Roman emperor Diocletian’s persecution of Christians in A.D. 303; another that it came from georgós, the ancient Greek word for “farmer”; and the third, most memorably, that it derived from the Persian word gurg, which means “the land of the wolves.”

This ambiguity is in large part because of Georgia’s particular geography. The country was variably ruled by the Roman Empire for 200 years, the Arabs for close to 400 and, finally, for nearly 200 more, the Russian Empire, which included Soviet occupation. In the intervening periods, it was conquered by the Byzantines, the Sassanids, the Mongols, the Ottomans and the Safavids. “Tbilisi has been destroyed 26 times,” said Tamara Natenadze, the guide with Silk Road Adventures whom I spent my days with here. “Each time, a new city was built over the old one.” To the west of Tbilisi is the Black Sea, and to the east the Greater Caucasus Mountains. The range spans about 750 miles, running northwest to southeast, and is widely accepted to have the highest peak in all of Europe, the 18,510-foot Mount Elbrus. The country shares its northern and northeastern borders with Russia, its eastern and southeastern ones with Azerbaijan and its southern one with Armenia and Turkey. Its west is hot and humid, its east generally dry, the lowlands black with swamps and forests. These contrasting heights and depths — towering mountains, deep valleys — create an astounding array of microclimates. In the summertime, snow-covered peaks are a short drive from coastal beaches shimmering with heat.

2. THE COUNTRY HAS long been an important logistical trading hub between East and West. During the time of the ancient silk trade, which, in Georgia, spanned the sixth to the 15th centuries, the country offered a crucial alternative to the better-trod routes of Persia (a kingdom that comprised what today is Iran, Iraq and Syria). Endless conflict between the Byzantium Empire and the Sassanian dynasty made the delivery of silk and other goods to the Mediterranean using Persian routes dangerous. And so in A.D. 568, the Byzantine emperor Justin II directed Central Asian merchants to a new northern route over and around the Caspian Sea, one that crossed the Caucasus and led to the Black Sea, from which traders could sail safely to Byzantium. Its distance and terrain made for a far more grueling trip than the Persian route, but it was safer and more profitable.

Archaeological excavations in the North Caucasus revealed that in the late sixth century and the first half of the seventh, most Chinese silk and other goods were brought to Byzantium using the Georgian route. The passage remained in use, though less frequently, until 1461, when the Ottoman Empire seized Trebizond (a northeastern successor state of the Byzantine Empire) after the fall of Constantinople. This brought an end to all trade along the northern routes of the Silk Road.

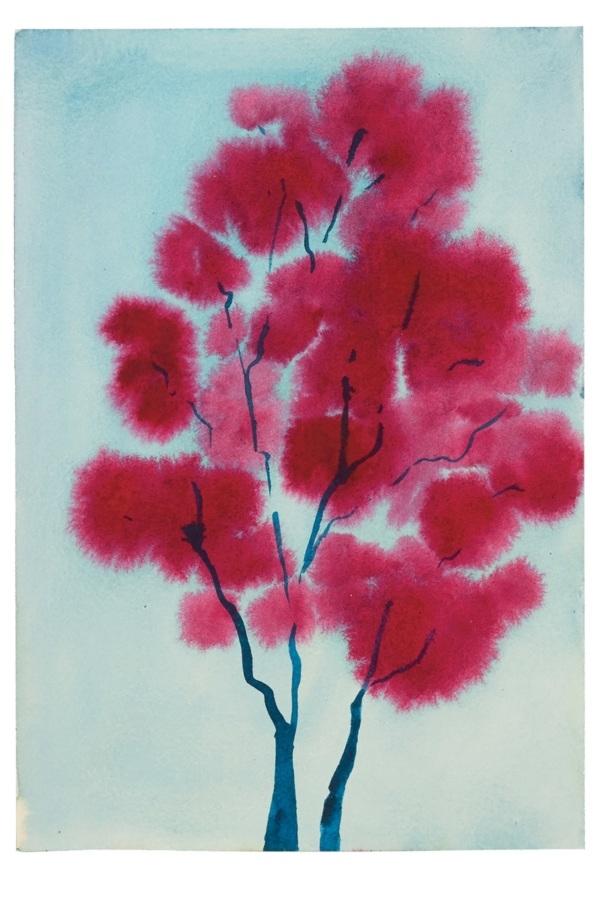

Bursts of crimson on dark branches are reminiscent of the fruit produced by the silkworm’s haven, the mulberry tree. Artwork by Nicolas Party. Photo by Weichia Huang

3. IN “THE TRAVELS of Marco Polo,” published around 1300, Polo, whose authorship is debated, describes Georgia as a nation of handsome warriors skilled in archery and courageous on the battlefield. He describes the country’s east-west passage as narrow and dangerous, with the sea on one side and impenetrable forests on the other.

“They have a great deal of silk and weave the most gorgeous cloths of silk and gold that have ever been seen,” Polo writes of Georgia’s sericulture, as translated by the British historian Nigel Cliff. “The sea that comes up to the mountain towards the east — is called the Sea of Ghel or Ghelan, or the Sea of Baku, and is 2,800 miles in circumference. … In recent years Genoese merchants have begun launching ships here and sailing on this sea. And this is the source of the silk known as ghilan.”

The sea he references is the modern-day Caspian Sea, and the presence of Genoese merchants there speaks to how far the silk trade had evolved by Polo’s time. In the fifth century, some believe, the Georgian king Vakhtang Gorgasali introduced silk and silkworms to his country, at around the same time that he rebuilt Tbilisi as the capital of eastern Georgia. Before silk was brought to Georgia, it was virtually unknown in the region, even though it had crossed from east to west along other trade routes, having found its way to the Roman Empire centuries earlier. Small pieces of silk dating back to the first century A.D., for example, have been discovered in Aradetis Orgora, an archaeological site along the banks of the Mtkvari. But over the following centuries, silk production would expand across Central Asia and into the Caucasus, and by the 12th century A.D., Georgian silk was, by some accounts, in such demand that it was being exported in large quantities to Italy.

Many scholars believe that Polo relied on eyewitness accounts of Georgia to dictate “The Travels,” and only a few are convinced that he later managed to visit the country himself. This conclusion is drawn from a sharp parsing of his chronology, but likely also because some of his details feel too fantastical to have been observed firsthand. He tells, for example, the story of a monastery on a glittering lake in which fish miraculously appear at Lent and then vanish just as quickly. Embellishments aside, though, his more grounded observations allow us to imagine a past that many people here have managed to keep alive today.

Party illustrated a selection of patterns from garments worn by secular figures depicted in frescoes in Georgian churches. Here, a fragment of a head scarf worn by the female King Tamar of Georgia (1184-1213) from the Bertubani Monastery near the eastern reaches of the country. Artwork by Nicolas Party. Photo by Weichia Huang. Source textiles pattern courtesy of the Art Palace of Georgia

4. IN 1887, THE Caucasian Sericulture Station was founded in Tbilisi by Nikolay Shavrov, a scholar of the natural sciences. The organization’s mandate was to preserve and advance sericulture throughout the Caucasus, and in 1891, it erected an edifice that accommodated a museum.

Housed in a soaring red brick building in central Tbilisi, the State Silk Museum — with its mansard roof, colonnaded porch and windows crowned with Persian-style arches — perfectly fuses Classical, Gothic and Islamic elements. As I entered through a pair of towering wooden doors, I was hit by a wall of cold air. The foyer was dark, its high ceilings lit with low-burning lights and pale sun. The walls were gray and dull green, the paint flaking away in huge leaves so that the brick showed through. I could smell nothing, as if even the dust wasn’t stirring.

As we took the wide expanse of stairs up to the permanent-exhibition hall, I noticed small plaster ornaments on the pillars and arches depicting silkworms in their various life stages. We reached a narrow doorway that opened onto a long room of glass-fronted cabinets filled with specimens and artifacts: sprays of nut-brown pupae; cocoons white as cotton balls from India and China; boxes for transporting eggs, inscribed in Georgian, Russian, Armenian, Ottoman, French, Italian and Greek; dyes made of plants, minerals or aniline; kimonos of bright silk; raw threads collected from around the globe. There was even the entire 13-foot-long root system of a white mulberry tree — its leaves are the main food source for silkworms — hung on the wall and enshrined behind a pane of glass.

I felt both the beauty and the bizarreness of it, standing among those marvels of a faded world. There are several approaches to silk-making, but to produce silk of the highest quality, one must kill the pupae. Cocoons are thrown into vats of boiling water rather than allowed to open naturally so that they will lose their sericin, a natural glue. If a pupa is not killed, the moth releases proteolytic enzymes in order to make a hole in the cocoon, which can shorten or damage the silk fibers. In India, Hinduism deterred silk makers from killing the pupae, and their silk was therefore considered inferior. But Georgian silk involved killing the pupa in the cocoon: A single silk tie takes about 110 cocoons; a blouse, some 630.

The silk trade in Georgia died a slow death. In the 1850s, an infectious disease called pébrine threatened to decimate the silkworm population worldwide. In 1969, an outbreak of disease-causing mycoplasma killed many of Georgia’s mulberry trees, and silk production was drastically compromised. The final death knell came, surprisingly, with the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, which brought with it the destruction of markets rooted in traditional arts and crafts, the looting of collectively owned machinery and the end of cooperative farming.

Miraculously, however, the actual worms were preserved — it was the techniques to transform them into silk that were largely lost. A local university fed and housed the worms when production was halted, and continues to do so, single-handedly saving the Georgian breed. But preservation is costly, and the department relies on volunteers, some of whom still handpick mulberry leaves for the worms to eat.

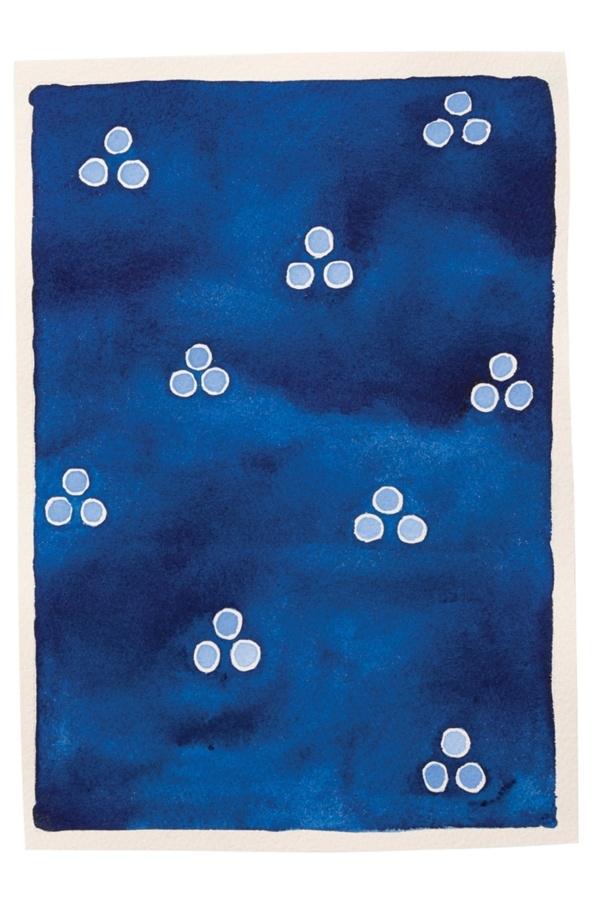

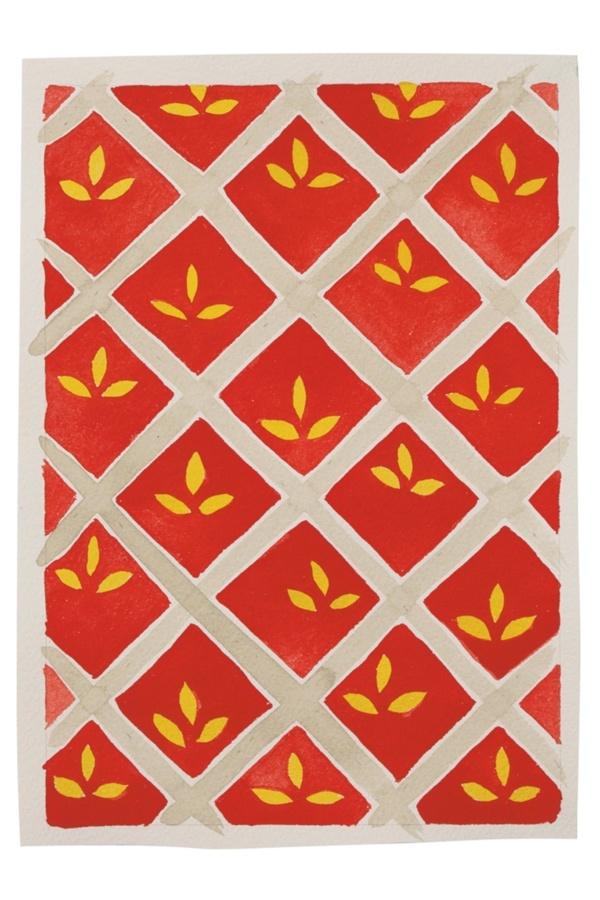

A pattern from “Stavrai” a 14th-century fabric from the Sapara Monastery in southern Georgia. Artwork by Nicolas Party. Photo by Weichia Huang. Source textiles pattern courtesy of the Art Palace of Georgia

Later, I went to visit Nino Kipshidze, an art historian and textile artist who lives in what is known colloquially as “the blue house” or “the house with laces.” Originally built in 1897, the house is a classic example of late 19th-century Tbilisian residential architecture, its neo-Baroque facade merging beautifully with the fine wooden lacework of its extensive balconies. It is also one of the last of the original grand houses in Tbilisi to have been continuously inhabited by the same family, though this fact feels a little fudged: During the Soviet era, the central government carved up the home’s ground floor into apartments. In a decades-long act of faith, the original family bought the apartments back one by one.To make her art, Kipshidze arranges, in a collagelike manner, new textiles with bits of discarded cloth — silk, linen, satin, velvet, whatever is at hand — and sews them onto a larger cloth canvas, creating compositions of people or still lifes of flowers and fruit. As we walked the worn wood floors of her small studio, she explained that some pieces took hours to finish, others years. She seems to be creating an art in which nothing is wasted. Castoffs are treasured, the rags of the past torqued into surprising reflections of the present. Studying a woven landscape, you thought instinctively of silk being transported through the north centuries ago, and felt you were staring at a history made whole again.

5. THE DAY WAS bright when Tamara and I set out for the Kakheti region, east of Tbilisi, to visit the Monastery of St. Nino at Bodbe. We passed a man selling juice out of a pickup truck, pressing the fresh fruit with a metal clamp right there on the road’s shoulder. His face was deeply lined and expressionless. When he handed me a cup of fragrant pomegranate juice, I noticed his thumbprint on the inside, black with oil, near the rim.

A light snow had blanketed the ground by the time we arrived. Up the hill, mottled ruins rose from the bright snow with a startling suddenness. The monastery was erected in the ninth century, but its ruins were plastered over centuries ago and adorned with frescoes. The central one of the Virgin Mary was pocked with age but also by violence. Bullet holes had blinded her eyes and those of the angels who flanked her. This had been done by the Soviets. You could be sent to Siberia, in those years, for practicing a faith. But the inner walls of the ruins were ringed in black: The Georgians would sneak in, under cover of darkness, to pray. There was no nave to hold their candles, so they stuck them directly onto the stone walls, scorching the rock.

From the hilltop, we stared out over the Alazani Valley. In the distance, looking almost artificial against the blazing blue sky, loomed the grand Caucasus Mountains, dark and towering. No different, perhaps, from when the first silk-carrying caravans passed through them in A.D. 568, so long ago.

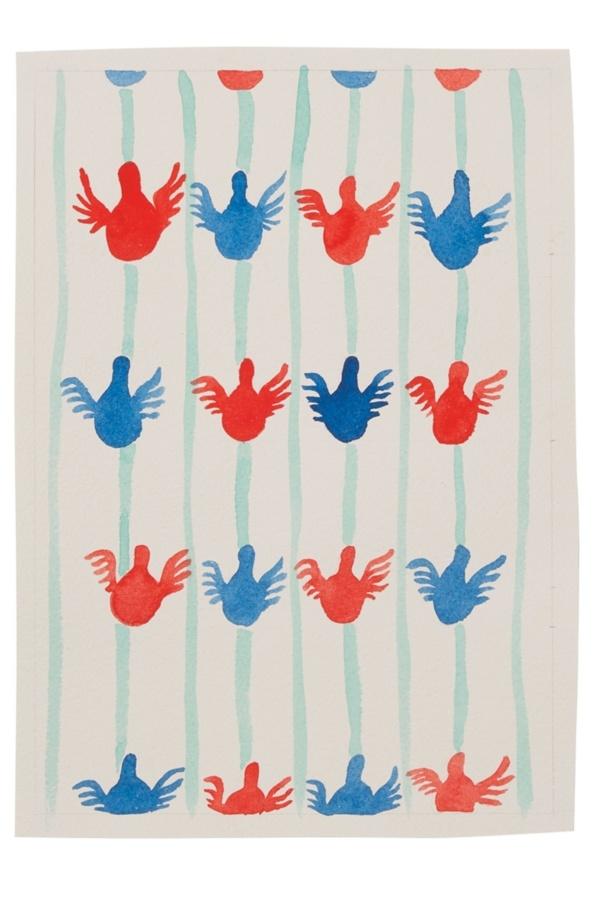

A pattern from “Oqronemsuli,” a 16th-century gold-embroidered fabric from the Gelati Monastery in western Georgia. Artwork by Nicolas Party. Photo by Weichia Huang. Source textiles pattern courtesy of the Art Palace of Georgia

6. MY FINAL STOP was to visit Lamara Bejashvili, who lives on a nameless street in the village of Kvemo Magharo in Kiziki, one of the smaller districts of the Kakheti region. She was well-known beyond the region for the silkworm farm she keeps in her backyard.

In her small dining room cluttered with a silk loom and jars of pupae suspended in liquid, Bejashvili had laid out bread and homemade quince jam, pears soaked in honey, local kiwis and tiny winter grapes purposely left to hang on the vine past the warm season so the sweetness gathered in their half-shriveled skins. A petite, elfin-faced woman, she told me she was descended from a long line of silkworm harvesters. She was 5, perhaps even younger, when she first began helping her grandmother, learning how to extract silkworm oil from pupae. The oil, she claimed, is miraculous: It cures migraines, hair loss, skin issues, inner-ear pain and ear infections. Injected, it purifies the blood. It also aids in improving circulation. When I pressed her for details — Was this scientifically proven? How was it extracted? — she demurred. The art of silk is an art of secrets.

Still, Bejashvili spoke of silk as if it were a living thing. She told me of its history — of how, in the days of the silk trade, silk gut was coveted for its use in stitching up wounds in surgeries because its threads possess a natural antiseptic. She told the story of a brain-cancer patient she knew who’d wrapped her head in silk cocooning every day, removing the wrapping only to bathe. After three months, she claimed, the woman’s tumors disappeared.

Bejashvili stood and, reaching her hand into a jar, extracted several silkworm skins. They were light gray, shriveled things with brown flecks attached, stray pieces of pupae. She encouraged me to eat one, and at first I shrank away. Then I placed one in my mouth: It was almost entirely tasteless, more a texture than a flavor, all at once spongy and crunchy. The longer I chewed, the spongier it became.

“It helps with fertility,” she said.

Outside, we picked our way through the snow alongside whining gray kittens toward a wooden shed. Bejashvili dragged open the doors and a soft barnyard smell wafted out: This was where the silkworms were housed. On a series of slatted wooden beds that almost resembled children’s bunk beds lay hundreds of white cocoons on dried leaves. The silence was punctuated by the creaking of the wood as it warmed in the draft from the open door. It was winter, all the mulberry was dead, and the silkworms had just finished their cycle, their eggs preserved to restart the farm in the springtime. The utter calm, and the clear reverence Bejashvili had for her worms, made me feel I was in a church.

“The silkworms need to be babied,” she said. “When I am late to feed them, they raise their heads when I enter. Their wings make a light crackling, buzzing sound. When they eat the mulberry, they make a noise like hard rain.”

7. LATER THAT EVENING, as Tamara and I made our way to Sighnaghi — a beautiful town east of Tbilisi surrounded by a sprawling 18th-century fortress built to ward off northern invaders — we stopped to walk along the fortification. High up on the icy corridor, overlooking the mist-bound streets, I thought of Bejashvili and her silkworms. I recalled her love, unembarrassed and direct. “Silkworms are very democratic,” she had said. “A silkworm would never impede another silkworm from eating — they are not a society like ants. They are very peaceful. Each silkworm is concerned only with its own journey.”

They were all women, those who had dedicated their lives to preserving silk culture. I thought of how passionately each felt connected to silk, how fiercely each defended it. For them, exploring sericulture was less a resurrection than a continuance. They were not dredging up a dead art but instead insisting that the art had never died, and that with steady nurturing, it never would. Their work was part of a fight to preserve the greater culture, to clarify and honor Georgia’s heritage as they understood it, even as globalization and human neglect threatened its loss. I thought of Bejashvili’s swift gestures as she held a white strand of newly spun silk in her small fist, the thread so strong neither of us could break it; I recalled Kipshidze pacing her studio, her voice quiet and almost somber as she showed me a piece from which faces were cut from bright fabric. It struck me then, as I was leaving, just how much of this place — not only its sericulture but its people, the monastery with its candle-blackened walls, all of it — was a long conversation with its ghosts, with a past that can never be past.

Esi Edugyan’s most recent novel is “Washington Black” (2018). She lives in Victoria, British Columbia. Nicolas Party is at work on a mural for the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, which is slated to be completed this summer; his exhibition “Sottobosco” recently showed at Hauser & Wirth gallery in Los Angeles.