September 22, 2020

Download as PDF

View on Brooklyn Rail

Installation: (Nothing but) Flowers. Courtesy Karma, New York.

The title of this spectacular show of 59 artists should be: These Are Not Flowers. Only Magritte’s admonition keeps us from confusing nature and art, though of course such confusion is the inevitable result of this floral avalanche. When do flowers cease to be nature and become art? When cultivated in massive numbers, like tulips in Holland? When they are cut? The Greeks created poignant “gardens of Adonis” to honor the seasonal god loved by Aphrodite: gardens of cut flowers that would, like the god himself, quickly wither. 17th-century Dutch still-lives and portraits used cut flowers as moral warnings about mortality and the wages of sin.

Our allegories tend to be Freudian, so we view flower paintings through a Georgia O’Keeffe optic as sexual metaphors. And then there is the ultimate artistic issue: beauty. Undefinable, beauty is a factor in flower painting simply because flowers are linked to sentiment. We react emotionally when the subject is flowers. Pansies, with that irresistible puppy face on their petals, are the obvious case in point.

So, what does an artist as unsentimental as Amy Sillman produce when she decides to paint flowers? 12 stunning examples where sentiment is displaced into formal structure. Untitled (2020), a 15 1⁄4 by 11 1⁄2-inch acrylic on paper, depicts pansies—but the flowers, arranged so there is a progression of color from darker to lighter—are pushed off to the right side. The left is a cloudy, somber void, so the subject ceases to be flowers and becomes instead the blank abyss versus the creation of visual images as justification of artistic being. Marley Freeman, who combines dazzling color with a quasi-Cubist take on still life in Noise of Birds (2020) also pushes her image forward to dominate the painterly field. This close focus is an alternative to traditional still life, which organizes the canvas in Renaissance-style perspective.

Reggie Burrows Hodges, Last to Leave, 2020, acrylic and pastel on linen, 45 × 45 inches ; 114.3 × 114.3 cm

Jane Freilicher carries this verisimilitude to its logical conclusion in Cat on Velvet (1976), where the titular cat is framed by potted flowers and the background is a cityscape viewed from a high window. Freilicher’s traditionalism is echoed and modified by Nicole Eisenman, whose Still Life with Takis (2020), creates a perspective space on the canvas, effectively rendering Freilicher’s “slice of life” abstract. This removal of still life from all context has its source in Albert York, whose undated Pink Daisies in Glass Jar does for flower painting what Giorgio Morandi does for depictions of bottles: those daisies are no longer things of any world but York’s imagination. This is not to imply a progression or a loss of sentiment in form: in 2020, all uses of flowers and landscape are valid. Verne Dawson’s triptych Primary Flowers in Yellow, Blue, Red (2020) plays with a dream landscape populated by human figures wandering in an environmentalist nightmare, while Reggie Burrows Hodges’s Last to Leave (2020) depicts a black figure carrying a fresh bouquet as an offering, but to whom and for what occasion remains ambiguous.

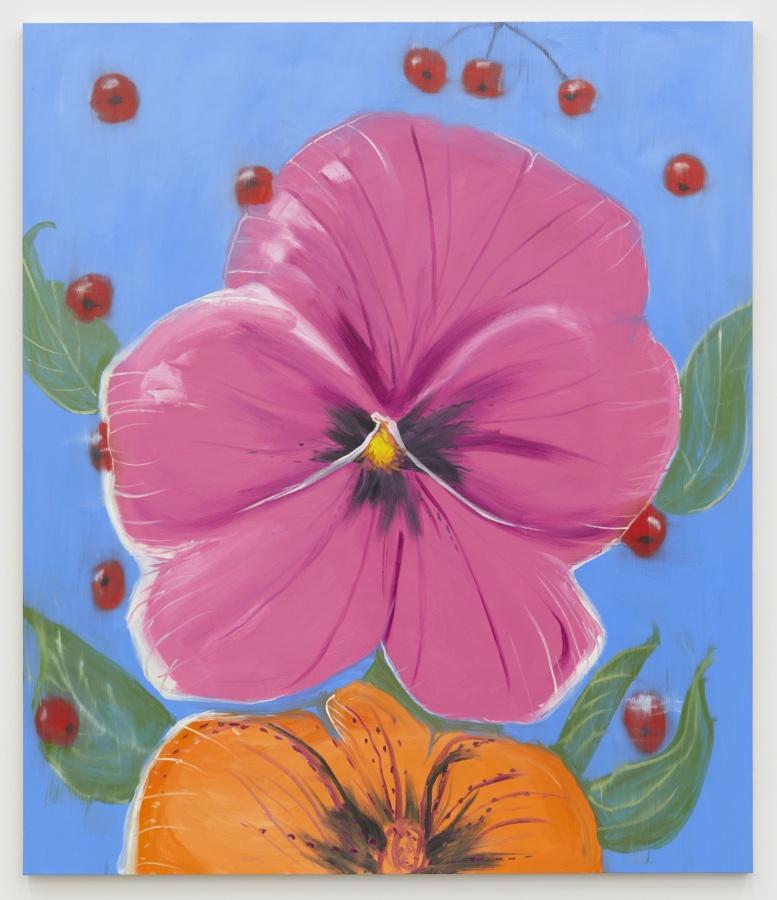

But what truly fascinates in this vast show are works that explode off the canvas. Alex Katz, in Untitled, orange-pink (2019), a large, 66 by 48-inch oil on linen, simply dazzles with a tour de force experiment in color. Much of Katz’s early work is landscape painting, and here it is as if he frees himself of all restraint. It is not the flower but the clashes of color that matter. The same is true of Ann Craven’s Pensée (Big Pink, Orange, on Blue with Cherries), 2020 (2020), an 84 by 72-inch oil on canvas. Craven, unlike Katz, stays close to nature—the pansy again—but here she immerses us in the flower itself as she recreates it. Color, patterns, even trompe-l’oeil: all of Craven’s signature tools, but deployed now in such a way that her powers are fully released.

Ann Craven, Pensée (Big Pink, Orange, on Blue with Cherries), 2020, 2020, oil on canvas, 84 × 72 inches; 213.36 × 182.88 cm

What about a flower painting without flowers? James Harrison includes six excellent watercolors of various flowers, but the last work in the show, following the check list through Karma’s two venues, is WALK IN THE WILD FLOWERS (2020), a modest 26 by 30-inch acrylic on stretched paper. The title is repeated from top to bottom in a subtle interplay of greens and yellows. A Concrete poem or conceptual piece, this work points the way to entirely new visions of flowers.

(Nothing but) Flowers is wildly diverse; it defies summary or generalization. Its utter vitality demands direct experience.