October 2021

Download as PDF

View on Harper's Magazine

Untitled, by Henni Alftan

Sheila and I were best friends from age ten to thirteen. I lived four blocks from our grade school and she two. She’d wait for me to pass her house in the morning and then we’d fall in step as we entered the building. From then until five-thirty in the afternoon—when our mothers demanded our presence at home—we were inseparable. After the summer we turned thirteen, something unimaginable happened: Sheila was no longer in front of her house in the morning when I passed, she no longer saved a seat for me in class, and after school she simply disappeared. At last it registered that whenever I spotted her, in the hall or the schoolyard, she was in the company of a girl new to the school. One day, I approached the two of them in the yard.

“Sheila,” I said, my voice quivering, “aren’t we best friends anymore?”

“No,” Sheila said, her voice strong and flat. “I’m best friends now with Edna.”

I stood there, mute and immobilized. A terrible coldness came over me, as though the blood were draining from my body; then, just as swiftly, a rush of heat, and I was feeling bleak, shabby, forlorn, born to be told I wouldn’t do, not now, not ever.

It was my first taste of humiliation.

Fifty years later, I was walking up Broadway on a hot summer afternoon when a woman I did not recognize blocked my path. She spoke my name, and when I stared at her, puzzled, she laughed. “It’s Sheila,” she said. The scene in the schoolyard flashed before me, and I felt cold all over: cold, shabby, bleak. I wouldn’t do then, I wouldn’t do now. I would never do.

“Oh,” I said, and could hear the dullness in my voice. “Hello,” I said.

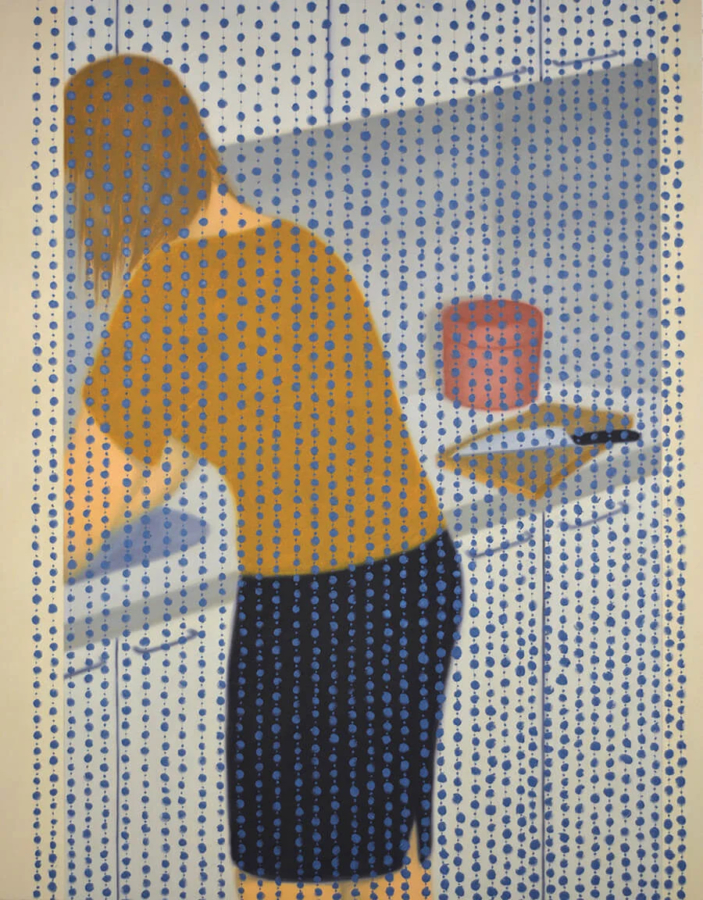

Reminder, by Henni Alftan. All artwork © The artist. Courtesy Karma, New York City

Anton Chekhov once observed that the worst thing life can do to human beings is to inflict humiliation. Nothing, nothing, nothing in the world can destroy the soul as much as outright humiliation. Every other infliction can eventually be withstood or overcome, but not humiliation. Humiliation lingers in the mind, the heart, the veins, the arteries forever. It allows people to brood for decades on end, often deforming their inner lives.

In Jeanne Dielman, the Belgian director Chantal Akerman demonstrates that exact proposition. The film is deliberately static, seeming to unfold in real time (it runs for three and a half hours). We are present during three days in the life of a thrifty widow with a teenage son. She cooks, cleans, shops for food, polishes her son’s shoes, turns the lights on when she walks into a room and off when she leaves. And, oh yes, every afternoon she turns a trick. The trick is always some respectable-looking burgher whose coat she removes, brushes, and hangs up as though it were her husband’s. Then one day we follow our protagonist and her client into the bedroom for the first time, where we see her lying submissively on the bed while the man on top of her humps away. The camera plays on her face: we see her eyes wandering aimlessly about, as we’ve seen the eyes of many women in the movies enduring unwanted sex. Then, suddenly, without a hint of what’s coming, she picks up a pair of scissors and stabs the trick to death. The End.

I remember sitting glued to the seat when the screen went black, shocked but somehow not surprised. In an instant I realized: this is for all of them, including the dead husband. In or out of marriage she’s been turning this trick all her life, lying beneath some man who pays the bills and for whom she has no reality. Why be surprised that such a deal, sooner or later, might produce the twist in the brain that only a stab in the chest can accommodate?

There are many things we can live without. Self-respect is not one of them. One would think the absence of self-respect would resemble much of a sameness, but the circumstances that can make people feel bereft of it are as variable as persons themselves. A psychiatrist who interviewed a group of men imprisoned for murder and other violent crimes asked each of them why he had done it. In almost all cases the answer was “He dissed me.” On the other hand, I have a cousin, a doctor, who feels humiliated if he’s shortchanged in a grocery store. His wife, too: if another woman is wearing the same dress at a party, she feels humiliated. I once had a mother-in-law whose critical observations amused me; my husband’s next wife felt humiliated to the bone by them. She used to call me up and hiss into the phone, “Do you know what that bitch said to me this morning?” repeating sentences I had experienced as harmless. Then there is the testimony of Primo Levi in his concentration-camp memoir, Survival in Auschwitz. Levi tells us that given the massive amount of death and destruction going on all around him, it was somewhat remarkable that the humiliation of humiliations, the one that remained ever fresh in his mind for the rest of his life, was the moment when a Kapo, finding nothing to wipe his greasy hand on, turned to Levi and wiped it on his shoulder. That was the moment when Levi understood viscerally what it meant to be seen as a thing.

I believe the exaggerated response to humiliation is unique to our species. In feeling disrespected, each of these persons—Levi, the men in prison, my cousin, my ex-husband’s wife—felt they had their right to exist not only challenged but very nearly obliterated. Their inclination then—each and every one—was to crawl out from under the rock that held their prodigious capacity for shame in place, and stand up shooting. When we speak of ourselves as an animal among animals we misspeak. That is exactly what we are not. A four-footed animal may go berserk if attacked by another four-footed animal and not rest until it kills its attacker, but it will not experience the vengefulness that the walking wounded do when humiliated.

In a review by the critic David Runciman of a book written by the cricketer Shane Warne, I learned that Warne had wanted to be an Australian rules footballer but hadn’t been good enough. When it turned out that he was brilliant at cricket—one of the great bowlers (pitchers) of all time—he took that path to fame and fortune. But he played the game “with a sliver of ice in his heart.” He didn’t necessarily hope to inflict injury on the batsman, but he definitely hoped to make him look a fool. “Deep down,” Runciman writes, Warne wanted the batsman “to feel like shit, as bad as he once felt when he got the letter that told him he wasn’t good enough.”

What is remarkable here is how tenaciously Warne held on to the memory of having failed as a footballer. Every time he acted viciously on the cricket field he was reliving the moment when he imagined himself being discounted, holding the memory close to his heart, feeling warmed by its live fire, convinced that it energized his talent. Runciman does not say what Warne does with his outsized attachment to the wrong done him now that he’s retired from cricket, but we have plentiful other examples of what happens to those who allow a sense of humiliation to hold them hostage all their lives.

When Harvey Weinstein was identified publicly as a sexual criminal, some wondered why he needed to force himself on nonconsenting women when surely there were many in Hollywood who would have slept with him without any struggle. The New York Times columnist Frank Bruni was right when he wrote that Weinstein’s “hotel-room horror shows had as much to do with humiliation as with lust.” The question then was: Whose humiliation did Bruni have in mind, Weinstein’s or the women’s? The answer is both. Think of all the taunting rejections Weinstein must have endured before he found himself in a position of power. How those memories must have traveled daily through his nervous system. How his skin must have crawled every time he looked in the mirror. What recourse did he have, primitive as he was, but to displace all that inner coruscation onto the women he felt free—legally (he thought) and culturally (he knew)—to strong-arm into servicing him? For such a creature no amount of reparations can ever be enough. The only thing that will do is to enact the crime of humiliation again and again in an emotional melodrama wherein it matters not who is the principal and who the supporting actors.

Beads, by Henni Alftan

The first time I understood humiliation as world-destroying was the morning I watched the World Trade Center evaporate from a street corner in Greenwich Village and found myself thinking, This is payback for a century of humiliation. I have subsequently discovered that a wealth of scholarly literature argues that a national sense of humiliation is, more often than not, a key motive in a country’s decision to go to war. Evelin Gerda Lindner, a German-Norwegian psychologist affiliated with the University of Oslo, has spent her professional life hypothesizing humiliation’s central role in starting, maintaining, or stopping armed conflicts. A country understands itself (for whatever reason) to be discounted in the eyes of the world at large and passes down that sense of national insult, generation after generation, until a day arrives, however far in the future that day may be, when it requires retribution. Historians have observed that after its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, an emotional sense of having been humiliated dominated the politics of France right up to the outbreak of war in 1914; a similar humiliation, doled out to Germany after it lost World War I, led to the rise of Adolf Hitler and a level of vengefulness that nearly destroyed the Western world.

On the ground, that devotion to national insult is translated into what passes between the individual persons on either side. It is vital that the soldier refuse to see the man in enemy uniform as a fellow creature, otherwise he might not be able to pull the trigger; the best way to assure this refusal is to destroy the irreducible humanity all persons believe themselves to possess.

Primo Levi speaks often of the Nazi practice of “useless violence,” by which he means that even though everyone in Auschwitz—guards, gatekeepers, commanders—knew that all the prisoners were headed either for the gas chamber or a bullet in the head, they were nonetheless beaten, screamed at, made to stand naked and to endure a roll call that kept them at attention for an hour or two several times a week, outside, in every kind of weather.

Before the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, I thought Americans incapable of inflicting such horrors. After Abu Ghraib, I realized that Americans were as willing as the nationals of any other country to inflict the kind of humiliation that would make it a matter of indifference to the prisoner whether he lived or died.

In April 2011, The New York Review of Books published a letter written by two law professors, protesting the conditions under which the U.S. Army whistleblower Chelsea Manning was being held: in solitary confinement, asked every five minutes the question “Are you okay?,” and the very week that the letter was written, forced to sleep naked and stand naked for inspection in front of her cell.

The law professors pronounced this treatment tantamount to a violation of the U.S. criminal statute against torture, and defined the Army’s methods as, among other things, “procedures calculated to disrupt profoundly the senses or the personality.” Indeed. I think if I were forced to stand naked in public it would definitely disrupt my personality—profoundly. The piece was headed private manning’s humiliation.

Humiliation commands the shape and texture of the works in which the following characters appear: George Eliot’s Gwendolen Harleth, Emily Brontë’s Heathcliff, Alexandre Dumas’s count of Monte Cristo, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Hester Prynne, Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, Herman Melville’s Bartleby, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Gatsby, Edith Wharton’s Lily Bart, Richard Wright’s Bigger Thomas. Many of these characters are made to suffer materially, but their material pain is as nothing next to the immaterial pain they suffer simply by being in a position that inflames the disgust and anxiety of those who seem to hold all the cards but need the tormented inferior close by—just to make sure.

Of these characters, the one whose destiny always stops me in my tracks is Gwendolen Harleth, from Eliot’s 1876 novel, Daniel Deronda. She could pose for a public statue dressed in Grecian robes on whose pedestal is written the single word humiliation. Gwendolen is young, beautiful, marvelously selfish, and at the age of eighteen, already knows that marriage for a woman is slavery. But her widowed mother and sisters are on the brink of destitution, so marry she must—the richest man who will have her. Enter Henleigh Grandcourt, a character so broadly drawn he’s a caricature of the evil Victorian aristocrat: remote, possessed of a scorn for humanity strong enough to cut through steel. While courting, Grandcourt is calculatedly patient, considerate, even generous, and Gwendolen is lulled into forsaking her fear of losing her independence, imagining that she will easily manipulate him to her own satisfaction. Once married, however, Grandcourt quickly displays the special contempt reserved for a prize that, now secured, is no longer valued. He never lays a hand on Gwendolen, hardly ever inflicts himself sexually, or even cares much about how she occupies herself. But she is constantly made to be aware (very much like Isabel Archer in The Portrait of a Lady) of the prison her husband’s iron will (sanctioned by law and social custom) has constructed around her. Before a year has passed, Gwendolen realizes her marriage is a life sentence.

There is a moment in the book that I have always found to exemplify the derangement of the senses that everyday domestic humiliation can lead to. Grandcourt possesses a set of family diamonds meant to be worn in a woman’s hair. Gwendolen hates the diamonds, as she now hates and fears her husband. One evening as the two are preparing to go out to a party, Gwendolen parades before Grandcourt in all her silk-and-satin beauty, hoping to put him in a good mood. She asks if her appearance pleases him. He looks appraisingly at her:

“Put on the diamonds,” said Grandcourt, looking straight at her with his narrow glance.

Gwendolen paused in her turn, afraid of showing any emotion, and feeling that nevertheless there was some change in her eyes as they met his. But she was obliged to answer, and said as indifferently as she could, “Oh, please not. I don’t think diamonds suit me.”

“What you think has nothing to do with it,” said Grandcourt, his sotto voce imperiousness seeming to have an evening quietude and finish, like his toilet. “I wish you to wear the diamonds.”

“Pray excuse me; I like these emeralds,” said Gwendolen, frightened in spite of her preparation. That white hand of his which was touching his whisker was capable, she fancied, of clinging round her neck and threatening to throttle her; for her fear of him, mingling with the vague foreboding of some retributive calamity which hung about her life, had reached a superstitious point.

“Oblige me by telling me your reason for not wearing the diamonds when I desire it,” said Grandcourt. His eyes were still fixed upon her, and she felt her own eyes narrowing under them as if to shut out an entering pain.

Gwendolen wears the diamonds, and from then on dreams daily of an escape from her life that can be achieved only through death, either hers or his; soon enough she cares not which. The problem is solved when Eliot has Grandcourt fall off a boat while on holiday, and allows Gwendolen to watch, mesmerized, as he drowns, begging her to throw him a rope. She is twenty-two years old; her life is over.

Put on the diamonds. For years, I could hear the menace in Grandcourt’s voice whenever I saw or felt a woman struggling to break free of a despotic husband or lover. The piteousness of her position—that of one born to sanctioned subordination—always seemed emblematic to me of all the sadism allowed to flourish in intimate relations, doomed to end one fine day with a twist in the brain that can no longer bow beneath the yoke.

The tales of harassment in the workplace that surfaced when the #MeToo movement erupted in 2017 made my head swim, so wide-ranging were the accusations. From an arm rub and comment about a sexy dress to physical assault, they revealed behaviors that were simultaneously condoned as acceptable and experienced as denigrating. Among these tales I found particularly haunting precisely the homeliest examples of the sort of sexual offenses that have been shrugged off for generations, those that typified the instrumental use men and women commonly make of one another.

I imagine a woman walking into her office every workday for years, her throat tight, her stomach in knots, ready to swallow the dose of medicine she has to down if she is to hold this job. She speaks of this vile ritual to no one because she knows the men would laugh and the women roll their eyes, so commonplace is her complaint; but day by day, month by year, it feels as though something vital in her is eroding: some sense of personhood she was becoming aware of at exactly the moment she felt she might be losing it. It is the helplessness of her position that gnaws at her—the shock of realizing she has no agency in a culture that accepts as normal that which she experiences as degrading.

In 2017, when such women were coming out of the woodwork, their faces contorted with rage, their voices hissing and spitting, sending out a tsunami of resentment that threatened to drown all of us—women and men alike—they were demonstrating that if the insults go too long unaddressed, they might one day bring down a civilization.

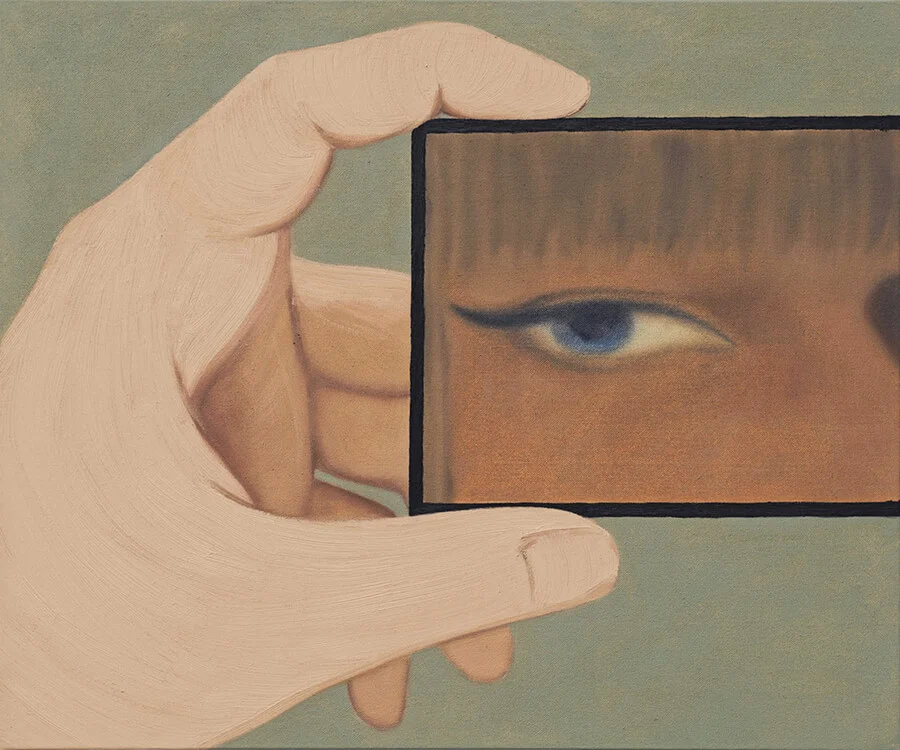

Self-Portrait, by Henni Alftan

Why does it hurt so much, do so much damage, twist us so horribly out of shape? Why does life seem unbearable—yes, unbearable—if we feel discounted in our own eyes? Or perhaps a better way to pose the question is to turn it around and ask, as a wise woman I know once did, Why do we need to think well of ourselves? Ah yes, I thought, when she put it that way, why is it not enough to be fed, clothed, and sheltered, given freedom of speech and movement? Why do we also have to think well of ourselves?

The question haunts every culture: no matter who, no matter where, we crave an explanation for why we are as we are; we manufacture bodies of thought and faith, century after century, that hold out the promise of an explanation that will assuage, if not our suffering, at least our brooding. Sigmund Freud, whose analytic thought concentrated on curing us of the inner divisions that make us vulnerable to self-hatred, hit upon an explanation that for the longest time offered the greatest hope; out of his empathic imagination arose the therapeutic culture, armed with its encyclopedia of theories designed to address the dilemma.

Psychoanalysis explains that from the moment we are born we crave recognition. We open our eyes and we want a response. We need to be warm and dry, yes, soothed and caressed, but even more we need to be looked upon with interest and affection, as though we are a thing of value. Routinely, we get only some small amount of what we need, and sometimes we don’t get it at all. The emotional conviction that we are not worthy sets in. From this condition none of us ever wholly recovers. Mainly, our feelings go underground and we struggle on, in general doing to others no more harm than was done to us. Some of us, however—starting with those born into the wrong class or sex or race, or perhaps those whose physical appearance leads to mockery or rejection—are so damaged we obsess over being made to not think well of ourselves, and we become dangerously antisocial. The effort to overcome this primitive state of affairs is what preoccupies analysis, but all too often the endeavor drags on and on (and on!) while our demons refuse to relent; then therapy begins to feel like a romantic hope of salvation destined to fail.

In the 1940s, the social psychologist Erich Fromm asked the same question—in essence, why we succumb so readily to humiliation—and arrived at a place some distance, but not a great one, from that of Freud. Fromm’s thesis in his great work, Escape from Freedom, was a simple one; like Freud before him, Fromm did not hesitate to use the convention of mythic storytelling to make his insight vivid for the common reader.

In Freud’s case the story derived from the classics, in Fromm’s from Genesis. Human beings, he argued, were at one with nature until they ate from the Tree of Knowledge, whereupon they evolved into animals endowed with the ability to reason and to know that they felt. From then on, they were creatures apart, no longer at one with the universe they had long inhabited on an equal basis with other dumb animals. For the human race, the gift of thought and emotion created both the glory of independence and the punishment of isolation; on one hand the dichotomy made us proud, on the other lonely. It was the loneliness that proved our undoing. It became our punishment of punishments. It so perverted our instincts that we became strangers to ourselves—the true meaning of alienation—and thus unable to feel kinship with others. Which, of course, made us even lonelier. The inability to connect brought on guilt and shame: terrible guilt, outsized shame; shame that gradually developed into humiliation. If there was any stigma that survived the exile from paradise—that is, the womb—any proof that we were unfitted to make a success of life, it was this. How else to explain all the centuries in which human beings have been mortally ashamed of admitting they were lonely?

Where Fromm joins Freud is in asserting that the very development—consciousness—that brought about our rise and then our fall is the only one that can release us from this pervasive sense of aloneness. The problem is that the consciousness bestowed on us is just barely sufficient; if we are to achieve inner freedom, it is necessary that we become more (much more) conscious than we generally are. If men and women learn to occupy their own inspirited beings fully and freely, Fromm posited, they will gain self-knowledge and thus no longer be alone: they will have themselves for company. Once one has company one can feel benign toward oneself as well as others. Then, like a virus that had been stamped out, humiliating loneliness would surely begin to wane. This is a proposition we’re required to take on faith.

The great Borges thought it best to look upon our broken inner state as one of life’s great opportunities—to prove ourselves deserving of the blood pulsing through our veins. “Everything that happens,” he wrote, “including humiliations, misfortunes, embarrassments, all is given like clay,” so that we may “make from the miserable circumstances of our lives” something worthy of the gift of consciousness.

I’ll leave it at that.