August 3, 2021

Download as PDF

View on Artforum

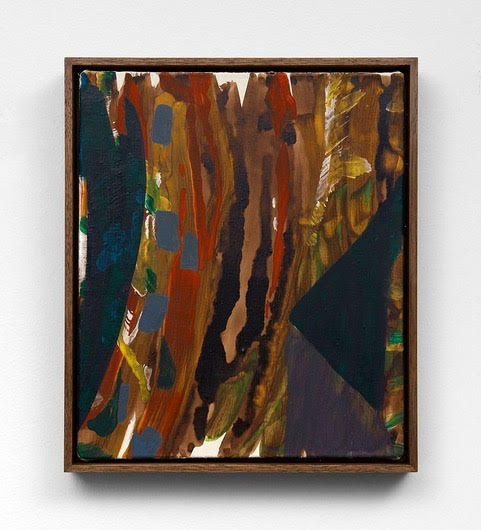

Tabboo!, Self-Portrait in Drag, 1982, acrylic on found advertising paper board, 27 × 20 1⁄4″.

Tabboo!, Tabboo! 1982–1988. New York: Gordon Robichaux/Karma Books, 2021. 140 pages.

ONCE UPON A TIME in the early 1980s, New York City’s East Village was cheap and scary, a petrified forest of desiccated industry. Among the ruins, fantastic creatures built worlds of fantasy and devised strategies to survive. They made themselves at home. One of these creatures was Stephen Tashjian, who had come to New York with a gaggle of friends, each full of promise, after graduating from the Massachusetts College of Art in Boston. Some were photographers: Mark Morrisroe, the prolific punk, and Jack Pierson, the moody glamorpuss. Others, like Pat Hearn, Tashjian’s bandmate in Wild and Wonderful (by all accounts as advertised), with whom he lived in one of those fabled ’80s SoHo lofts before Hearn started her famed gallery, did a little of everything.

One day in the mid-’80s, after Tashjian had settled into the East Village apartment still he lives in, he was out scavenging. Prior hauls had yielded rolls of paper meant to wrap fish and packaging for Pepsodent—both adequate, if hardly archival, substitutes for canvas. As he roamed Fourteenth Street, a building caught his eye: an abandoned glitter factory. The iridescent stuff dusted the pavement by the doors, beckoning him closer. In this case, what glittered was gold. “As soon as I opened one of the boxes and the sun hit the glitter, my head exploded,” Tashjian later told the gallerist Jacob Robichaux. “I grabbed as many as I could—maybe forty-five boxes—and ran home and back to get more.”

Tabboo! 1982–88, a new book jointly published by Gordon Robichaux gallery and Karma Books, tells this tale and what happened after. He mixed the first part of his last name with the name of his beloved, artistic aunt Boo. Tabboo!—the fine artist, the drag artist, the East Village legend—was born. He mixed the glitter with acrylics, and, voilà, his accomplished Neo-Expressionist portraits became fully realized, brilliant in all senses. No shade to the earliest work: The creamy crust of acrylic in 1982’s Self-Portrait in Drag perfectly captures the moment pancake makeup becomes sheet cake frosting. But he knew how to put that glitter to work. That year’s Connie Francis at San Janero Festival documents a teen idol in decline, her fresh face sinking like a pop song down the charts. A yellowing collar shimmers with cheap sparkles. She waves hands clenched into claws while wearing, as John Waters would imagine her in his memoir Carsick, “more makeup than Divine ever did, but without the joy.”

Like Divine, Tabboo! used drag as a palette, a kind of fabulous tool kit. Post–Drag Race, performers have often argued that they dress up to find themselves, that a beat face is like Oscar Wilde’s mask that tells the truth. Tabboo!’s riotous performances and extravagant canvases revel in the masquerade. Which isn’t to say he can’t capture an essence: Portrait of Clark Render from the Green Dimension, 1986, places the famed Dueling Bankhead in a glistening space he fully inhabits. Render’s gaze radiates off the canvas, off the page of its twenty-first-century reproduction, and undimmed into the ether; in the right corner, his knee and elbow meet as if to form a prism. The subjects of Tabboo!’s still lifes appear paused in animation: In The Beautiful Ones, 1986, a small statuette of a bow-tied poodle looks up in loving concern at an Asian doll as blossoms sprout from the ceramic head of a flip-haired female figurine, all before a luxurious expanse of red dabbed with glitter to suggest sequin curtains or the grain of an old Hollywood film. His early work is explicitly queer, if not particularly explicit, perhaps finding, as Jerome Caja did, a dignity in the gimcrack and the fey. The young Tabboo! is exceptionally adept at botanicals; on his stagy canvases, a flower’s blooming is the role of a lifetime. You Can Only Get It in New York, 1986, victoriously plants a bodega bouquet inside a coffee can before an expanse of glitter-strewn blues and yellows so vibrant and inviting that the current vogue for immersive van Gogh installations should turn his way next.

Tabboo! went on to find underground fame as a star of the Pyramid and Mudd clubs, clucking like a chicken in a ripped pink shift in the documentary Wigstock. “It’s natural,” he crowed in tones both spoofing and sincere. Who cares what might cause something this much fun? He developed the groovy typography for Deee-Lite, helping them zoom the East Village sensibility into the global mainstream, then showed up in a few of Nan Goldin’s most tender photographs. He installed himself in the collections of MoMA and the Whitney. Today, one detects glints of Tabboo!’s insouciance in the moody extravagance of Salman Toor’s queer love letters and the bold backgrounds of Angela Dufresne’s empathetic portraiture. In him, younger artists can see a way of staying afloat in a New York scene—not to mention a global economy—in many respects even less hospitable now than when he took the city by storm all those years ago. But on these pages, and in the recent Manhattan exhibitions at Gordon Robichaux and Karma from which the book pulls, he’s discovering his own visual vocabulary. His work communicates in Greek key motifs, in whooshes of acrylic stains: royal purples, goldenrods, electric blues. Statement eyelashes curlicue in vast spirals, gleefully psychedelic and seriously silly. In Alphabet, 1985, he invents a sui generis grapheme and signs his birth name below as if in lights. Today, we’re all speaking his language.