September 2, 2020

Download as PDF

View on Culture Type

Installation view, Illusory Progression, True to Myth, and Rhizogenic Rhythms, Frieze Sculpture 2020, Rockefeller Center, New York.

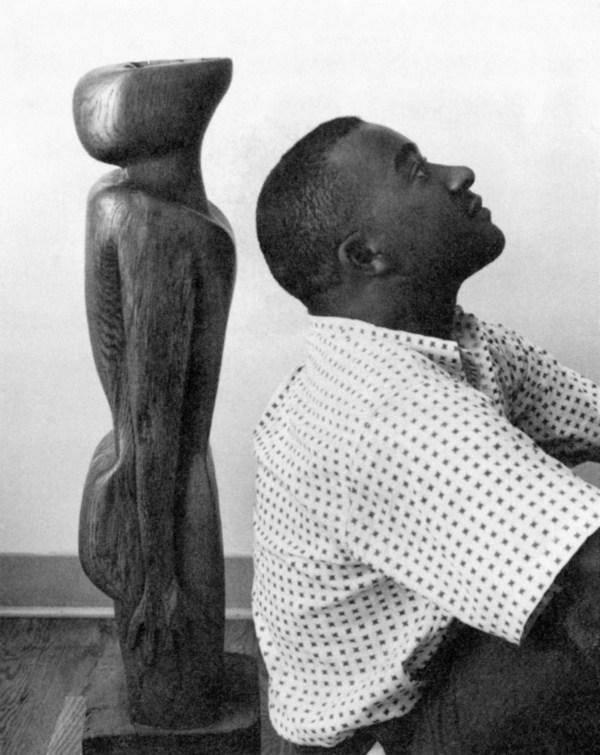

USING HAND TOOLS, Thaddeus Mosley carves abstract, modern forms out of felled logs from Western Pennsylvania. A trio of sculptures by Mosley is installed at Rockefeller Center near Fifth Avenue in front of the Channel Gardens. These latest works were created specifically for Frieze Sculpture 2020 at Rockefeller Center. The free outdoor public art exhibition officially opened Sept. 1 in New York and features six international artists, including Mosley.

For 60 years, Mosley’s chief material has been wood. For Frieze Sculpture, he produced bronze works based on existing wood sculptures, employing a multiple cast method for the first time. The sculptures represent what the artist describes as a “weight and space” concept.

“It’s a spatial concept where the thing may look like it’s floating. The heaviest part is up and not down,” Mosley said in an oral history interview with The History Makers, adding that it’s a common concept he mastered in the late 1960s.

Composed of multiple parts, his sculptures defy logic. The structures work because he begins with a broad enough base to provide foundational support and then he ensures balance and stability by establishing a center of gravity and engaging traditional pinning and joinery techniques.

The approach sounds rigorous, but when it comes to the creative process, Mosley is improvisational, expressing himself in the moment. He rarely develops models or maps anything out in advance.

“Some people make models for everything,” Mosley said in a recent conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist published in a new book. “I knew a guy who would make models in clay that he would then carve into stone. I always thought that his models had more interest, more spirit, and more spontaneity than his stone pieces. The only way you can really achieve something is if you’re not working so much from a pattern. That’s also the essence of good jazz.”

Mosley has lived in Pennsylvania nearly his entire life. He was born and raised in New Castle, a small industrial town about one hour north of Pittsburgh, where his father worked in the coal mines and his mother was a seamstress.

After high school, Mosley served a short stint in the U.S. Navy and then enrolled in the University of Pittsburgh studying English and journalism. He worked part-time for the Black-owned Pittsburgh Courier for a bit, then landed a job with the U.S. Postal Service. He stayed at the post office for 40 years, earning a reliable income enabling him to take care of his family, while working in his studio nights and weekends.

He’s 94 now and still goes to his studio where he lifts and carves heavy hardwood logs, usually walnut or cherry.

“Sometimes there’s something in the log, something is already a beautiful shape in the log and I more or less exploit that…,” Mosley said in a recent Carnegie Museum of Art (CMOA) video.

“That’s the joy of it for me, is navigating these ideas and see if they come to fruition and when something turns out well or at least stands up, I’m pretty happy. The sculpture once its projected into space, you want to say, ‘Well, does it move? Does it dance? Does it do anything? Does it stop you or can you walk by like you saw a paper bag on the street?”

Mosley began visiting the Carnegie Museum of Art during college. The institution was right across the street from the university. He was drawn to the displays of modernist sculpture. It was at a local retailer in the 1950s, however, that inspired him to test his own creativity.

The entire 11th floor at Kaufmann’s department was devoted to Scandinavian design, including furniture. “It was a way of living with art. They wanted a fortune for those pieces, so instead I thought, ‘I can make that,’” Mosley told Obrist.

He did. Self-taught, he developed his own practice. Utilizing a mallet and chisel, he realizes biomorphic shapes and modern silhouettes with textured and patterned surfaces. In addition to wood, he has worked with stone and metal.

Among his influences, he calls Isamu Noguchi “one of the greatest American sculptors” and favors Constantin Brâncuși’s seldom-shown wood sculptures. Mosley also appreciates African sculpture.

“What I like about African art is that every object is unique, nothing is repetitive. The tribal arts in Western and Central Africa have probably the most diverse sculpture in the world,” the artist said to Obrist.

Over the decades, Mosley participated regularly in the Carnegie Museum’s programming, including public talks and solo exhibitions in 1968 and 1997. In 2018, Mosley was featured in the 57th Carnegie International.

In February, his first solo exhibition at Karma gallery opened in New York. About two-dozen works made between 2003 and 2018 were on view, but the show was cut short by the COVID-19 shutdown. (The show can be experienced in an online viewing room.)

A publication was produced to accompany the exhibition. Contributors to the monograph include Jessica Bell Brown, Connie H. Choi, and Ingrid Schaffner, the curator of the Carnegie International who wrote the introduction. Artist Sam Gilliam dedicated a short poem to Mosley and Obrist conducted an interview with the artist.

Gilliam’s verse begins, “Thad Mosley / A friend since forever.” He continues calling his friend and fellow artist “a jazz critic, post-man, father, keeper of trees anywhere- / old trees, round trees, big trees, heavy trees.” Gilliam concludes: “…We talk often to summarize and to keep it going. / Thad is always there, fresh, new, FOREVER. Congratulations.”

In his conversation with Obrist, Mosley spoke at length about his life and practice. He mentioned adventures about hanging out with jazz musicians in Pittsburgh, including Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and a good friend, trumpet player Tommy Turrentine. The artist also noted the significance of his birth year: 1926. “Ray Brown, Miles, Coltrane, Joe Harris the drummer—we were all born the same year,” Mosley said.

Then he lamented the current state of the musical art form and connected it to his practice. “What’s happening now with jazz is that everyone has become so academic, everything is so schooled out. The old jazz was a lot more spontaneous,” Mosley told Obrist.

“I’ve heard artists say that they weren’t going to do something until they knew exactly what they were doing. I never know exactly what I’m doing. I think you’re always learning, always trying. To me, that is the interesting part of being an artist.” CT