Spring/Summer 2020

The sculpture of Thaddeus Mosley started with an appreciation of the wooden figures that appeared in Scandinavian design, a binding element that brought together the interiors he saw in books and department store displays. These images sparked in Thaddeus the idea that he too could try his hand as a sculptor. Looking also at the work of Isamu Noguchi and Constantin Brancusi, and the African tribal art of the Dogon, Senufo, and Bamum people, among others, Thaddeus well and truly followed through. This was in the ‘50s, and, with no formal training, while covering sports for the Pittsburgh Courier and working shifts for the US Postal Service, Thaddeus started fashioning works of art from wood that he’d picked up at the local hardware store. Looking at his work today, nearly seven decades later, his sculptures have an almost figurative aspect, relating perhaps to the human body, recalling the jazz cut-outs of Henri Matisse, but monumental in scale, and made from organic material yet appearing strangely futuristic at the same time. All that aside, Thaddeus insists that ‘the main thing is dealing with the log’—that the material itself is where the real reckoning takes place. His sculptures often involve a number of pieces growing one on top of the other, each limb weighing a hundred pounds or more, but the final effect being one of apparent levitation. The sculptures are meant to float.

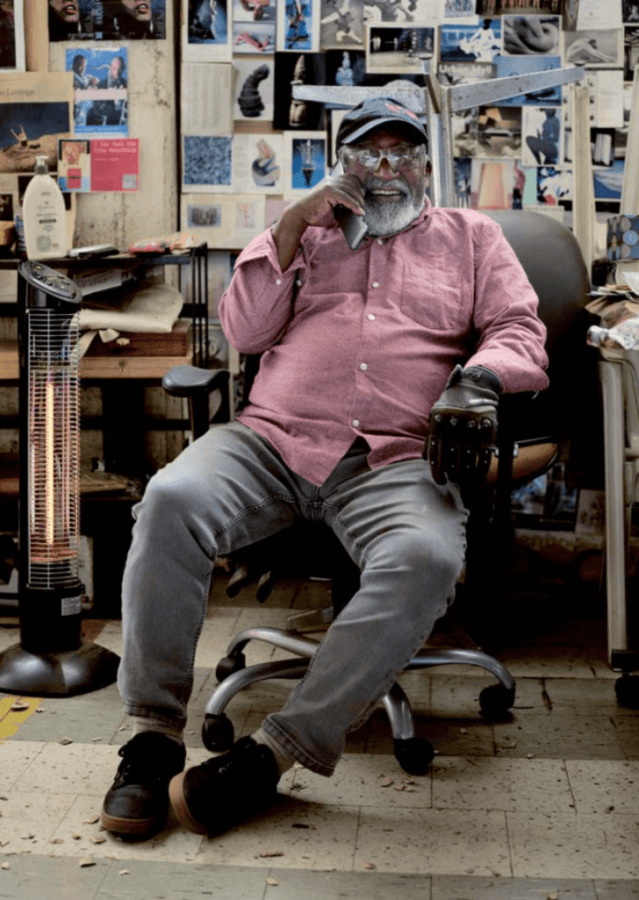

Thaddeus was born in 1926, close to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in the kind of small town that fed the area’s steel and mining industries but also grew on the back of institutions bequeathed by the Carnegies and the Mellons, industrialists and philanthropists who channelled money towards libraries, museums, and schools. The Carnegie Museum and Syria Mosque performance hall were both close by, the first being free and open to the public and home to the International, a contemporary arts fair that gathered works from around the world and deposited them on Thaddeus’s doorstep, an occasion he’s never missed once. Through the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts, a community-minded hub for different artist groups, including one of the oldest in the US, and long-standing friendships with artists like Sam Gilliam, Thaddeus was able to extend his own education in the arts through a disarmingly simple method of learning by looking. In 1968 he held his first show at the Carnegie, where he returned again in 2018 to exhibit at the International. These places—Pittsburgh, the Carnegie—are names that constantly return to the story. They’re the site of much of Mosley’s activity over the past decades; his work has been largely, and wrongly, neglected outside his hometown, a fact that’s started to change with a recent exhibition at Karma gallery in New York and an upcoming show at the Rockefeller Center, now that Thaddeus is in his 94th year. The following interview looks back at this history, but Thaddeus himself is by no means stuck in that past. Meeting him, one is immediately struck by his energy; he’s sharp and intensely engaged, more alive than many people half his age. At a dinner in New York for the opening of his show, someone asked if he’d had a good day. His reply: ‘I always have a good day’.

Photo: Tim Schutsky.

Photo: Tim Schutsky.

How long have you been in the house that you live in now?

Since 1985. I used to live on the South Side, and I had a little house in the back that was a whisky still during prohibition. It had two floors, and I would use that as a studio at the time. Where I live now, I work in the basement a lot, but most of the time I work at my studio in Casey Industrial Park.

That’s the same studio you’re in now?

Yes. Well, it wasn’t the same studio when I first went there, but I was in the first building on the same property. Casey has around 55 acres of industrial buildings in the park.

When you first started making art, where were you making it?

I lived in a housing project up in St Clair Village and I just worked in the basement. But I wasn’t really thinking in terms of showing stuff or anything like that till the first Three Rivers Arts Festival in Pittsburgh. When I showed up it was in 1959, but I was just making stuff for myself. And I guess I’m still making stuff for myself.

Right, you just make it.

One thing I learnt years ago—in 1966, I was offered my first show at the Carnegie Museum. I had a year and a half to do the show because I had a full-time job. It sounds like a long time, but after a year, I only had six sculptures. I realised that you can’t work for a show; you have to be working so that when the show comes, you have plenty of sculptures to pick from.

Before you started making art, you were doing other creative things. You were doing photography, and that’s also when you published the magazine, Compositions in Black and White.

We had a writers’ club way back then. I was actually a journalism and English major in college. I didn’t study art. I always thought I would like to be a magazine writer, but I ended up working for the Courier newspaper, mostly covering sports. I always liked sports because I was an athlete myself; it was something I already knew. I didn’t know golf and tennis, but I knew boxing and basketball and football, the things I played myself.

So you started writing and then you had this group of writers who were doing poetry and fiction and short stories.

Yes, everything.

Then you were combining photography. You were actually making art with the photography and maybe you didn’t realise it at the time?

I thought of the photography as a photographic art because we were trying to do poetry and other stuff that the photography reflected or combined. So in that sense, yeah. I started making my first objects later on. I was very much interested in Scandinavian design, the Danish and Swedish furniture of the day. I bought some of the furniture. The displays always had these decorative fish and birds and stuff like that. I never even saw a book on Scandinavian design without sculpture somewhere in the room. I got the idea that this was the integral part of the whole setup. When I saw the fish and bird I said, ‘Well, I can do that’. That’s how I started.

So you went and got some materials?

Materials are easy to find; you can go to a hardware store. I used two-by-fours. They used thin teak wood, but I just used two-by- fours. One thing about that type of wood is it’s easy to carve, but it still gives you good definition. Then I had a friend who was a painter, and we used to go to all the Internationals, particularly across the street at the Carnegie Museum. That was pretty much my training.

Going and looking.

Yes, I was always looking. Then there was a collector in Pittsburgh by the name of G David Thompson. He had owned this small steel mill. It was a sort of middle-class, working neighbourhood, and he bought this house. This was a multimillionaire; you wonder why he bought a house there. But in his yard he had a Fritz Wotruba, a Giacometti by the door. He had an Aristide Maillol. On his roof he had a Calder, and we used to drive past his house just to look at the sculpture. One day he came out and there were three Afro-Americans on the edge of his lawn, and of course one thing Americans always have been apprehensive about is a black male, so he said, ‘Do you guys—what are you doing?’ We said, ‘Well, we’re looking at the sculpture’. He says, ‘Do you know who you’re looking at?’ We said, ‘Yes, that’s Giacometti. That’s a Maillol, and that’s Calder’. We didn’t know who Wotruba was. So he said, ‘How do you guys know? None of my neighbours know what this stuff is. They think I’m crazy’. I said, ‘Well, yes, because they don’t know anything about art. Well, we try. We’re all sculptors and we’re trying to learn’. He said, ‘Gee, that’s really great’. I guess he felt so happy that someone recognised it.

Photo: Tim Schutsky.

Art is like a secret language in a way.

The art circle is very compressed, and any place has very few people that live art, like artists and people who appreciate it and feel it’s important to have art around them.

When you started becoming interested in art, did it become the most important thing? The thing that you thought about the most?

No, I thought about a lot of things. You have a family. You have to think about that responsibility. You have a job. It probably became the most interesting part of my life. Listening to music and looking at art was very important, and still is. I surround myself with art. Someone was at my house saying, ‘Gee, it must be really nice just to sit and look at your stuff’. I said, ‘Oh, yes, that’s why I have it’. If you decide you’re going to collect, you’ll find that your surroundings, your environment, take on a lot more vitality and meaning and interest. Most people think that art is for rich people and you can’t do this and that. I said, ‘Well, students sell, they almost give art away’. I always remember this one woman; she had a silver necklace. It was really great, and when someone asked her, she said, ‘Oh, I bought it from a student over at Carnegie Mellon University who needed money to buy more silver’. If you bought it in the store it would’ve been maybe $2,000 or so, but she got it for a couple of hundred dollars.

Just so they could make more work.

I think in most places there are student galleries and stuff like that. You don’t have to start off with a Picasso. There’s a lot of people doing very interesting work that are totally unknown. The more you look into artbooks and stuff, the more you’ll get a feeling for what strikes you. But you also get a feeling for a certain type of quality.

It’s interesting because I didn’t go to art school and I started learning about art in the same way. I had a graphic design background. I started working with artists on these books, and I didn’t know anything about art when I started. But once I started working with artists, I got hooked on it, and maybe that’s why books have become so important for me: because it turned into my way of learning. When you were growing up, were there people around you in your family that had artistic interests?

Music-wise, but not in visual arts. I come from a mining town about 50 miles north of Pittsburgh. Everything around Pittsburgh was just mills and mining, all feeding the steel industry. So there was good basic education, like ABCs and stuff like that. Of course we had a choir. I sang in the acapella choir, but there is very little emphasis on visual art, and that didn’t start till much later on, at the University of Pittsburgh. At the time, I lived across the street from the Carnegie.

How did you start having this dialogue with different artists? You mentioned that Sam Gilliam came to Pittsburgh to teach and that’s how you ended up getting to know each other.

No, there used to be a little gallery called the Gallery of Fine Arts, near the Carnegie. They brought Sam Gilliam in to do a show of small paintings there. I know the people very well. The art community is very small and also, particularly, since there aren’t a lot of Afro- American artists in Pittsburgh per capita, well, they knew me. I’d heard of Sam because he’d been in Art in America in the early ‘60s. So there was a party, and he and I had the same sort of interests in music and stuff like that. We both liked sports. In fact, when I talked to him not long ago, his wife was complaining about him watching so much sports. Anyhow, we hit it off very well. And later on, I used to go down to DC and spend time with him. Then he got a job; he had three daughters in college at the same time, so he decided to take a job at Carnegie Mellon teaching graduate painting. Every Thursday night we’d go out and listen to music and have dinner. Sometimes he’d come to my house and I would cook dinner. We just got to be really, really good friends. We had a lot of attitudes that were similar. If we go back to the ‘60s and early ‘70s, there was an idea that a black artist must express blackness—these restrictions that to me don’t make any sense. Or they didn’t want white people painting images of African America. There were even people complaining about photographers photographing black people. I said that a good photographer can photograph anything.

Whatever they want.

Yes. And of course there were people who said that you must reflect the Afro-American community, especially if you’re an artist. I don’t think anyone should do anything unless they want to. You can paint nothing but black mountains if that’s what you want to do, and I don’t have to like it, but I think that’s the idea of art, particularly if you really believe in freedom. I don’t mean selective freedom for me or my group. It’s not really freedom unless everyone has the same privilege or the same right. But they had all these restrictions. I mean, there were people criticising Sam for doing abstraction. ‘Black people shouldn’t be doing that’, which is pure nonsense. That’s like saying white people should only be painting Protestant pictures or Catholic pictures or pictures from Ireland or Greece or wherever they’re from. That’s nonsense.

Someone was talking about certain artists recently, and I said, ‘Well, for me, some of these artists that go around with signs on their back, they get attention more for their persona than they get for the art’. Sam told me, ‘I got in a lot of trouble saying stuff like that recently’. I’m not jealous of anybody, and I don’t care what anyone does. At the same time, I don’t like that art and I don’t have to agree with it. But my combatant days are long over. So, Sam and I got to be on the same wavelength about a lot of things. We have pretty much the same sense of humour.

It was that attitude that art had to be completely open to be powerful, with no

restrictions at all.

Yes, it had to be individual. It’s what you want to do, not what someone else or any type of society wants you to do. You’re not being an artist for propaganda reasons or to prove that you’re equal or unequal. It’s not about proving anything. It’s about your idea of self-expression and what’s important to you as an artist.

Photo: Tim Schutsky.

It sounds so simple, but actually a lot of people don’t really think about it.

Well, they think about it, but what happens in any society is that in many situations you tempt ostracism, you tempt rejection if you don’t go along with the prevailing winds, or whatever is in vogue now. If you’re going to prove you’re black or Afro-American, we have a formula you got to follow. Of course, I know who I am, I know I’ve suffered it for many, many decades, but no one’s going to tell me what to do. And I can go back to situations in the early ‘60s where lot of black people said, ‘I’m not going to associate with any white people’. And I said, ‘Well, how are you go ing to do that?’ I knew people that had white friends, who rejected them. That’s nonsense. You are doing the same thing that you accuse other people of doing. If you don’t believe in discrimination, then don’t practise it.

It’s amazing you ended up meeting all these incredible people in Pittsburgh, like when Noguchi came through.

Yes, the main thing people have to remember is that there are a lot of people in the art world—and other types of worlds—that are from Pittsburgh.

Why do you think that is?

I think it goes back to the educational system. For example, my daughter decided she wanted to take violin. If you join the orchestra, you can bring an instrument home from school and play and practise. Joe Harris, a drummer from Pittsburgh, said that when he went to Allegheny High School, they had a symphony, they had a marching band, and they had a jazz band. The main thing was, the people that really had money, like the Carnegies and Mellons, built all those libraries and buildings. They paid enough so that the school system gave even poor kids an opportunity. Another thing, when I went to college, you could walk across the street to the Syria Mosque where the Pittsburgh Symphony played, and they would advise students to come over for the dress rehearsals when they wanted people in the audience. So it was all for free; you’d go over and listen to the Symphony.

Even Warhol, do you think that was part of his upbringing?

Yes, because he grew up in Oakland, where there’s the Carnegie Museum and the University of Pittsburgh, Carnegie Mellon University. He could walk to these places from South Oakland where he lived. None of it was that far away.

It’s inspiring, as you were saying, to live around things that you’re interested in. It’s like your house ends up becoming the history of all your relationships, interests, and connections.

Yes, there are a lot of people. This fellow came from Rochester as a woodworker, and now he’s made my living room coffee table and I have a desk upstairs in my bedroom that he made. But then there are a lot of artists that were in different groups and shared with different groups; some people are famous, some are semi-famous, and there are people that never really got noticed as an artist that are pretty phenomenal. There are all these people, and when you look you remember your conversations with them, how you interacted with them, and so forth. They aren’t just distant objects, whereas someone might have a de Kooning, but it’s just a history. In fact, we were talking about how in the old days there used to be so many artists’ parties. I don’t know if the young people do as many parties as we used to. We partied every weekend somewhere.

All groups of artists?

Yes, there’s a place called Pittsburgh Center for the Arts, they had 14 art groups based there.

All different groups?

They had a weavers’ guild, a printmakers’ guild, the society of sculptors. The Associated Artists was the main group, and they had their own floor, their own gallery, and they kept an office there. Everyone had an annual show, and that’s how I met Jack Larsen, the weaver, because the weavers’ guild had him come in.

Right, and they had a show of his work.

He brought his collection there, stuff he’d actually collected from African weavers. Not what he did, it was just his collection.

Which was also his inspiration?

Yes. There was that closeness. Back then there were always parties and meetings, and all that sort of stuff, because there were very few galleries in Pittsburgh at that time.

And you were in the sculptors’ group?

I was in two or three groups. In fact, they’re going to do a show of the abstract group sometime in May, and I’m going to have a couple pieces I did in the ‘70s put in the show. This is the 75th anniversary for the abstract group. We used to call it Group A. Of course, the Associated Artists is one of the oldest art groups in the country; they’re 110 years old.

Wow. And from that group, would you end up collecting or trading work with people?

It all depended if people bought stuff out of the shows. Some people traded, some people bought directly from artists. All sorts of things.

You also have the collection of African objects in the house.

Yes, it’s African tribal art. Jay Leff had a collection; he was a banker and he had a big collection of stuff. Then I met a couple African traders, guys that got it from the Ivory Coast. And there was a woman who had a store called Studio Shop and she sold mostly Scandinavian furniture and design things, but she also sold some African tribal stuff. That was a weird contrast, from Scandinavia to Africa.

Primarily wood?

She sold a lot of wood, everything from glassware to tableware, but she also sold lamps and furniture. It was one of the most popular stores among the art world. I bought stuff from her which I still have. Then I started buying when different African traders came, and this guy moved to Pittsburgh who’d had a gallery in LA.

Through that exposure, you started learning about all the different tribes?

I got tons—well, not tons, but maybe 20 books about African tribal art.

Right, and you really studied.

Yeah, same that I did with art. I was just interested in reading. And I was living not too far from the museum. Back in those days it was free, and so it meant you could go in anytime and see the shows and develop a taste of your own.

Photo: Tim Schutsky

Were you thinking about those interests and the research when you were making work?

You do think about it. When someone says ‘Ivory Coast’ and you think of Senufo, you think of Ghana and Sanwi, you think of Mali and Dogon, with Cameroon, you think of the people that did the beaded sculptures. You learn which tribe did what and from which country, because when people think of Africa, a lot of people think of it as one entity, but there are a lot of different countries there. They’re similar to the Native Americans here, like the boundaries we have between Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania—

They’re not the original boundaries.

They didn’t have those types of boundaries because they had the concept that you moved in a territory, you lived in a territory, but you didn’t own the territory. I think all these influences are very conscious ideas of what I do that relate to Brancusi or Noguchi or African tribal art. But sometimes it’s very unconscious, like, ‘Gee, I wasn’t even thinking of what this is related to’. The last sculpture I did, this woman came up and said, ‘This looks like a cross at the top’. I said, ‘No, it’s offset. It’s not a cross. It has to do with all the channels in the wood. It reflects the deep channel—this board channel on the top is connecting an idea’. She said, ‘Oh yes, I see what you’re talking about’.

I was looking at some of your sculptures and they felt very figurative to me. But you said that when you begin working on a sculpture, you’re really just starting with the material and how the wood is speaking to you.

I get an idea of what I think I would like to do, what I’d like to see happen, but I don’t have a real idea of how it’s going to work. So I’ll get to working and see how it formu- lates and comes into the form that I think is a really interesting sculpture. Most of it has the title ‘animated abstraction’. That’s what most of my stuff is about. Of course, people are always looking for objects and things: ‘It looks like a turtle’.

Animated abstraction; that’s how you describe what you do? Because there is this implied motion in the work.

Yes, I often point out that I think what tribal African art did has never really been explored enough. Because if you just take the way they saw space and the way they saw the shape in the wood and the way the tool marks were left in the wood, that gives it even more definition. Those are things that I try to use in what I do. It creates a rhythm, directs your eye, and stops your eye.

And you have also made some functional objects.

I’ve made furniture: my dining room table and three or four long benches. But I have amassed so many objects that they cover up the furniture.

And also the stools.

Yeah, I have made a lot of stools. I have fun making them. A lot of the time when I finish two or three big sculptures, then I think about what I would like to do next. I’ll cut logs for stools and start making three or four or five stools. I do that in−between, and it gives you something different to work on. And something to think about a little differently.