March 14, 2016

Download as PDF

View on Artforum

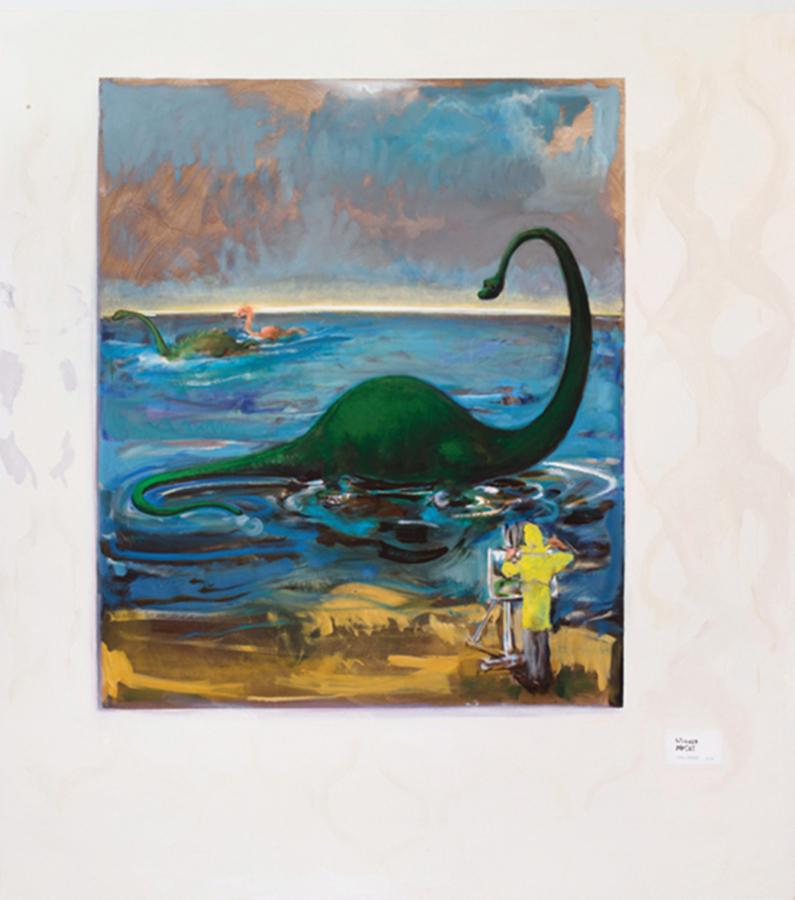

Verne Dawson, Winsor McKay, 2015, oil on canvas, 85 × 75 3⁄4 inches

Depicting such fantastical subjects as dinosaurs and even stranger hybrid creatures, as well as spaceship-like objects, the rather naive-looking paintings in Verne Dawson’s exhibition “Mermaid Money” at first seemed merely trite and self-indulgent. The exhibition’s title, however, hinted at what many of these works really are: searing commentaries on American consumer culture and its effects. One of the largest paintings in the show, Winsor McCay (all works cited, 2015) set the ball rolling. McCay, in case you’ve forgotten, was a cartoonist and animator whose images appealed to millions. His 1914 Gertie the Dinosaur is sometimes thought to be the United State’s first animated film. Enclosing Gertie’s image in its own painted-white passe-partout, Dawson “frames” this cherished emblem and then draws attention to the artificiality of the icon’s making by showing an artist in the process of capturing Gertie in paint. Though seemingly self-referential, the motif quotes one of the first frames in the movie, which commences with McCay betting a group of artists that he can bring the extinct animal back into existence quickly. The deftness with which he did so led the American Tobacco Company to offer him a fortune to develop an advertising campaign. Meanwhile, eager to exploit Gertie’s marketing appeal, the moguls at Sinclair Oil Corporation found another artist to draft a similar-looking dinosaur. By the early 1930s they had transformed it into a wildly successful corporate logo that stood for the power and resilience of their products. Ever since then, as W. J. T. Mitchell has pointed out, the dinosaur has been “an emblem of corporate gigantism” that is “linked with big money.”

Mermaids, a smaller work, directs attention to a related theme: the power of illustrators to create fish-women that generate big money. Although the mermaid mother and child don’t look exactly like Mattel’s Magical Mermaids Barbie and Krissy Dolls, they recall these toys’ inexplicable power to attract consumer dollars. They also conjure up the alluring fish-women displayed on Chicken of the Sea products since the early 1950s and more recently on the Starbucks coffee cup, who have likewise brought a catch of millions. Almost all of Dawson’s paintings critique, too, the gullibility of Americans, who eagerly snap up such commercial bait.

Unbridled consumer hunger is summed up in another work that features a gigantic inflated form inscribed with the word AVARICE. The term’s slow rise above a group of agitated naked figures, some of which seem to flee a seemingly empty towering structure in the background, conveys a deeply unsettling feeling. Titled Balloon (Avarice), the painting recalls the financial catastrophe caused by the massively inflated mortgage market wrought by America’s big banks less than a decade ago. Intimations of a doomsday nearly upon us also lend gravity to paintings showing small meteorites blazing to earth, unidentified flying objects gliding into sight, and bulbous clouds emitting radioactive fallout. Those concerns direct attention not just to present worries but to those of America in the 1960s, when Dawson came of age. Funny how the rumors of conspiracy and cover-up that back then characterized governmental and military disclosures on the subject of UFOs and aliens—not to mention the assassinations of JFK, RFK, and MLK—have come back to haunt us. Only now the anxieties revolve around terrorism and the secret efforts being pursued to stop it. Following such chains of association, Dawson’s work attains a potent political dimension that is lacking in the art of many of his contemporaries.