January 26, 2016

Download as PDF

View on Interview Magazine

When Mark Flood visits New York from his hometown of Houston, Texas, it is for a reason, and usually one that causes enough of a stir to preoccupy the art world for the length and aftermath of his stay. This month, Flood introduced five Houston-based artists the New York scene in a group show titled “The Future Is Ow” at Marlborough Chelsea. Including himself, Susie Rosmarin, El Franco Lee II, Paul Kremer, and Chris Bexar, the exhibition presents digitally altered paintings and videos alongside pieces that play with light and spatial order. The juxtaposed works are meant to spur conversations about imagined futures, but, as is Flood’s M.O., it’s a jarring, ugly, and at times hilarious prediction of our fate.

A few years ago, Flood came to New York during Frieze Art Week to stage a cynical homage to the art fair by presenting The Insider Art Fair, which included only his artworks. Last year, the documentary Art Fair Fever became his directorial debut. Regardless of his skepticism of the art market, Flood is also an avid collector of young artists (including the ones featured in the show), all which he at one point consolidated for a short-lived gallery, Mark Flood Resents. He writes the press releases for all of his exhibitions, which he also curates, frequently supplemented with home video quality exhibition trailers—a practice tied to his music videos, produced at a similar caliber.

Recently, Flood spoke with his longtime friend, the artist Will Boone, who Flood collects, is also originally from Houston, and has a two person show opening this week at Andrea Rosen Gallery. The two spoke about everything from a derelict, flea-infested studio to their shared hobby of reading biographies.

MARK FLOOD: I have Will Boone as the persecuting attorney.

WILL BOONE: This is crazy. Mark, how’s it going? You’re in Houston? I’m in L.A. at my studio…

FLOOD: I’m sitting in my studio. The assistants are at lunch. I was really tripping on your studio when I was there before. All the little bronzes really haunted my imagination. I can’t wait to see that work.

BOONE: Thanks. Let’s talk about Houston: I’m from Houston, you’re from Houston, we met in Houston. Do you remember how we met?

FLOOD: We met at that show at a church. I went to see it because I had been stalking James Burns ever since I saw his art on the walls of Annie’s Ice Cream. I bought your piece that had little boner pills in little plastic bags…

BOONE: I had been prescribed anti-anxiety medication and they were giving me so much anti-anxiety medication that I also had anti-narcolepsy medication. Then I sold it all as this art piece to you. James told me you were going to come to our show, but we didn’t know that you were an artist. You had given James a roll of canvas for free and then he gave me some; we thought you were this rich guy. So I came to your studio to install the piece and we ended up hanging out. The studio reminded me of Texas Chainsaw Massacre, but everything was paint instead of blood. [both laugh] It also reminded me of Lee Perry’s recording studio The Black Ark. How did you find that studio?

FLOOD: I’d been living on that corner for 10 years or more. There were two derelict houses across the street. I’ve lived in both of those houses over the years, but the house that we’re talking about had been nice, maybe 10 years earlier. Then there was this drug dealer who lived there. So I was driving around, looking for a new place and one of my roommates goes, “That place is available.” I found the landlord on the tax rolls and he didn’t even have a key to it. We put a ladder to an upstairs window and broke in. This guy had a dog and let the dog live there. It was infested with fleas. There were fleas all over me and I said, “Yeah, I’ll rent this place.” I had to wage an epic battle to get the fleas out. We threw away all of the stuff that was there. Then the guy who left the dog there rides up on his bicycle and still thinks it is his place. I’m like, “Dude, you’re out. You haven’t paid rent in a year. Your stuff is gone.” He didn’t believe me. He walked in and it was painted. He was shocked.

BOONE: I remember you said, “This is how you find a studio: You find the biggest place that looks the most fucked up. You write the address down, go to an office, and look up who owns it. You call them on the phone, they probably won’t even understand what you’re talking about, and you offer them a couple hundred bucks for the place.”

FLOOD: Yeah. That place was quite large, but a lot of it wasn’t useable. When we first moved in, I had two roommates downstairs, but their plumbing was worse than mine. Their entire bathroom dumped out the bathtub water into the backyard. It was real fucked up, but when you’re poor you’re just like, “Whatever.”

BOONE: What were you doing? Had you left school?

FLOOD: I was at The Menil Collection…I’d been banned from Texaco and I was about to be banned from Sound Warehouse, where I rented videos. I knew the framer at The Menil—actually at the Rice Museum, before they opened The Menil. He said he could get me a job to be the guard. They told me they would only hire me for half a day because they didn’t think I could handle the boredom. Once I got there, it became obvious that I knew about art and then I was on the inside. They needed a lot of people for the museum they were about to open and they rolled in this crate that had Dissecting Machines by Jean Tinguely. They said, “This is all in pieces and we want you to assemble it and write a manual of how to assemble it. We do not know how to assemble it. That’s your job.” I was like, “Wow, what a great gig.” It was just like that.

BOONE: When you started spending time there, were there certain artworks you had moments with or that really spoke to you?

FLOOD: Lots of things, their whole collection, but particularly the ancient things—the ancient Cypriots, antiquities. They have a lot of Cro-Magnon stuff and I got to play with that stuff, because I had to move it around and change light bulbs. Also, the 50 Max Ernst paintings, the Magrittes, the whole surrealism thing has seeped into my mind. My work, a lot of times, can look uncomfortably close to Max Ernst. I have to reel away from that. And I spent a lot of time with Yves Klein.

They had one Cezanne and it looked like it had been through the washing machine because it was so faded. There was no tonal range. One day, when I looked at it, it looked like the tonal range had been expanded because there were darker shadows around the trees. I was so used to that painting—I always went to it because I really like Cezanne—that I made a mental note to check it against the book. Another thing I noticed was there was a little X in it. I didn’t remember ever seeing that mark. So right before I left, I pulled out the catalog and sure enough, that X wasn’t there. So I went to conservation and somebody had outlined the trees with a black magic marker. We found five paintings they had altered.

FLOOD: It’s not where I started it, but I got a lot of posters to use from that place. It’s hard to imagine now, because everybody can print whatever they want, but back then you had to find these posters and I had to have multiple copies of them. I started those maybe two years earlier. There was this other record store, Real Records—they were more punk rock, whereas Sound Warehouse was more mainstream. I remember, in particular, getting Julio Iglesias 1100 Bel Air Place posters. There were two of them and people were really scandalized because I said, “I have take both of them. I can’t split them. I need both of them.”

BOONE: Then that’s the same as Julio Iglesias, which became a light box that was lit in New York City [at Max Fish], right?

FLOOD: Yeah, and the back cover of Tacky Souvenirs is Sound Warehouse. I know the guys at Marlborough Chelsea all used to drink at Max Fish.

BOONE: I think a lot of people did. For a long time, it was a very easy way to reference your work, to say, “Hey, you know the light box at Max Fish?”

FLOOD: People would introduce me that way. They would go, “This guy made the Julio.”

BOONE: So now you have a show at Marlborough Chelsea with four other artists from Houston: Susie Rosmarin, El Franco Lee II, Paul Kremer, and Chris Bexar. I was in school with El Franco at the University of Houston and introduced you guys. Then Chris and Paul were part of I Love You Baby.

FLOOD: I forgot you were part of I Love You Baby.

BOONE: I think I went three or four times. I was initiated at one point, where they made me dump a bucket of paint on my head. But what was I Love You Baby? How would you describe that?

FLOOD: I went to a birthday party Bexar and Kremer were there. They said, “We get together and paint. Why don’t you come?” I guess I was in a downward spiral with my life and wanted to make it worse, so I started going. They would all paint on the same painting at the same time. They had been doing it for years. It was all about getting really fucked up and acting crazy. I think they thought they would crush my spirit or something, but I liked it. To their amazement, I started coming every week. I started getting more fucked up than I had in a long time. Both Bexar and Kremer were involved with that. Bexar had his art on the side, which I always liked and thought could go places. Kremer had a super successful business designing websites. He knew all about the internet long before I did. But as far as their ambitions, they were all self-destructive, self-saboteurs. One day I asked them what they thought about the word “success” and it was things like, “Lawyers fighting. Everybody hating each other.”

BOONE: So let’s talk about Susie. I know she’s been your friend for a long time…

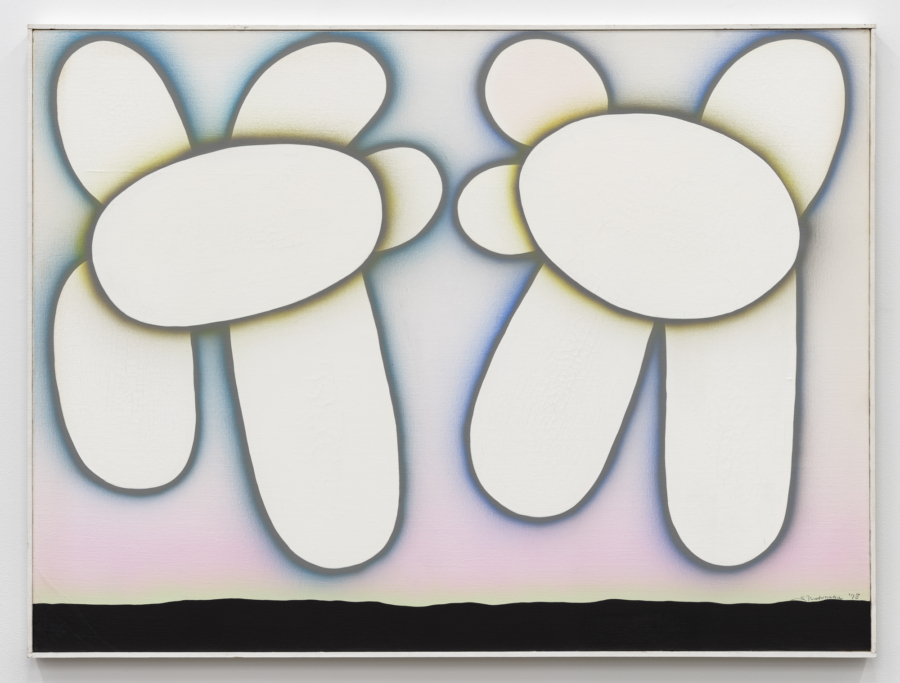

FLOOD: I met her in the ’90s. We weren’t that friendly at first, but we got used to each other. She lived in Brooklyn for a long time and I visited her a few times. When she started building the Flash paintings I always really liked them and eventually I started buying them. We’d hang out in Houston because I like hanging out with other artists. I can’t stand hanging out with normal people.

BOONE: It’s funny you say that because to some people it feels like you’ve isolated yourself by remaining in Houston. It’s interesting that you say, “I hang out in Houston with other artists” because a lot of people probably imagine you being down there by yourself, sort of like a fish out of water.

FLOOD: In New York it’s different. Artists are normal people; there are a million of them. It’s a normal gig. Whereas in Houston, I don’t know… I don’t really like hanging out with people at all, I guess, but if I’m going to do it, I’m going to hang out with artists because we have something to talk about.

BOONE: There’s another thing we can talk about: I know you read a lot and that you enjoy reading biographies. You’ve recommended a lot of books to me over the years and some have become my favorite books. [Les Chants de] Maldoror was one, and Manson in His Own Words. I remember you telling me that you really enjoy reading biographies of artists, that you find relationships you hadn’t thought of before, after you read the book. Once you said you really related to Renoir as an artist…

FLOOD: There’s an incredible Renoir biography written by his son. I did find a warped reflection of myself in this curmudgeonly painter who started off painting little landscapes. The main reason for artists to read artists’ biographies is to see these situations that happened to artists; they will all happen to you, too—the poverty, the criticism, the misunderstanding, all the different kinds of suffering that inevitably happen. It’s a lot better if you know that Matisse was sitting there after World War II with half his stomach removed and everybody treated him like shit until the day he died. For every big winner, there’s a bunch of big losers. It helps to know what it is really like to be an artist. If I had to educate a kid, I’d just say read a bunch of biographies and find out what life is really like.

BOONE: I remember one time I was in Jeff Elrod’s studio and he was reading one of the Allman brothers’ biographies. He was like, “I think everybody should have to write their autobiography as part of life. There will be a lot that no one wants to read, but everybody should have one.”

FLOOD: That’s a great idea. It makes you think of all the people who would’ve had biographies. F. Scott Fitzgerald didn’t want one. Duchamp didn’t want one. People didn’t want something to sum it all up. They’re right, too. A biography is always a flawed instrument. But something is better than nothing.

BOONE: I know that you write a lot—lyrics for songs, screenplays. You made a movie last year. Do you want to talk about it, Art Fair Fever?

FLOOD: It was great to become a movie director. It changed all of my ideas about entertainment. I liked it and I’m proud of my movie. I’m stuck in this place, where my basic indifference to the audience has made what I’m going to do with the movie a question. It doesn’t matter me that much, but it bothers a lot of other people who worked on it, like, “What are you going to with that movie?” Leave it sitting around molding for six years, that’s my plan.

I decided not to make it commercial. Instead, I went back to the three or four hour version and chopped it in half and made two movies. I decided to start showing one of those in the back rooms of my exhibits. I remember seeing movies that way when I was a kid; it becomes this experience. Whereas, if I put it online or tried to make a big deal out of it, I think it’d be more of a flop. As a real movie, it might be substandard, but as a crummy movie in the back room it’s so over the top because I spent so much money on it. My niece is involved in the Austin film industry, so she and her buddy produced it. All I had to do was pour shit loads of money into it and write a script. Those are both things I found out I can do. It’s a great way to waste money. I highly recommend it.

I thought someone else would direct it; I thought I would hand somebody money, like when you buy popcorn, and they would give me back my movie. But then I got involved in it. It was physically very grueling to make it. I felt like I was at death’s door the whole time. It was long days and screaming at people. I couldn’t keep up the thought of normalcy and politeness at all. But then it turned out surprisingly good. I watch it all the time.

BOONE: I really like the music videos that you make, too. I re-watched a couple of them maybe a week ago. I think my favorite is Bitch Move.

FLOOD: That was the first one. I didn’t really know how to use an iPhone camera and I said to my manager, “Will you help me edit this movie?” He said, “If there’s more than 10 minutes of footage, no.” That was my first lesson in filmmaking: don’t make a lot of extra footage. I kept that; it has no place in the art world. So as long as I sell some paintings to pay the bills, I don’t really care if people look at it or not. I like having those movies sitting there on Vimeo and YouTube. One of the weird things about the art world is how small the audience can be but it can still be important. If the right six people see it, I’m satisfied.

BOONE: What about the wrong six?

FLOOD: That’s when you get stalkers and hate mail. I have a lot of really gnarly stuff up in the show at Marlborough Chelsea, like fake Facebook profiles that I published—a corpse’s Facebook page and this turd’s Facebook page. I don’t know how to explain it, but they’re really gnarly. I had one person looking at them, they were tripping and asking me all these questions and writing down everything I said. I was like, “This person might be a police officer, maybe they’re going to do something to because I put pictures of naked people up on the wall.” But so far nothing.