Winter 2021

“Many of the painters I admire … are able to really paint out of themselves without the need to impress in particular. I hope I can develop the courage to get to that stage someday, as I realize the habit of simply making well-qualified work that does not really challenge some existing standards of form and aesthetics is also a symptom of the marketplace. I must always keep in mind to prioritize constant movement and experimentation over the acquisition of virtuosity.” – Matthew Wong, Studio Critical, 2013

As 2020 — surely one of the most collectively surreal and traumatic of recent years, thanks to the Covid-19 pandemic — plodded to a close, the artist Matthew Wong (1984-2019) delivered to the world a metaphoric postcard from the other side. His posthumous delivery took the form of an exhibition titled Postcards, which was organized by the New York gallery Karma — which represented the artist when he was alive, and now his estate — and on view at the nonprofit art space ARCH in Athens, Greece. The show consisted of twenty intimately scaled landscape paintings, ranging from 9×12 to 20×14 inches. In a year of unrelentingly bleak news reports and a seemingly unending stasis brought on by the virus, these impactful, spontaneous — perhaps searching — small works rendered in gouache acted both as a beacon cutting through our endless night as well as a poignant and melancholy reminder of the scintillating talent the world lost the year before.

Matthew Wong was a Canadian-born, self-taught artist who, after studying photography in Hong Kong, turned his attention to painting. From the start he was an omnivorous devourer of art history and techniques with the primary source of his painterly education being “Facebook, Tumbler, Instagram, and the reference section of the Hong Kong Public Library’s Central Branch.” Facebook in particular, as he told the blog Studio Critical in 2013, helped bring him “out of isolation and put images on public circulation for anyone to access and have a dialogue with.”

Wong’s paintings from his last three years reveal the lessons learned from established and historically important art- ists, such as Lois Dodd, Marsden Hartley, Edvard Munch, Alex Katz, and Vincent Van Gogh, and as you look closely at his landscapes you may see other reference points — the birch trees of Gustav Klimt, the Mediterranean landscapes of Henri Matisse and the repetitive impasto strokes of Yayoi Kusama, for example. Despite only beginning to paint around 2012, he generated an estimated 1,000 works before tragically taking his own life in October 2019 at the age of 35.

Matthew Wong’s paintings first entered my sightline in 2017 while I was researching the book Landscape Painting Now (D.A.P., 2019), within which his work was included. After having come across his work, I remember being frustrated that there wasn’t much to be found in print on him, nor were there significant traces of a digital footprint. There was a New York Times article reproducing the Last Summer in Santa Monica (2017) — a medium-size, nearly abstract seascape composed of nine of his trademark color bands, starting from umber browns at top, progressing to warm oranges, cool greens, and then ochres, with just a ghostlike rendering of the moon and a bird — but little else that gave a clear picture of what he was about, though at the same time I was intrigued as it was apparent that he deserved a much closer look.

This was especially evident when considering his unique sense of color, his approach to composition and mark-making, and perhaps most of all, the emotional tenor of the work. Like many great artists, his work was both borrowing from and nodding toward the past while clearly being of today, with a “post-Pop” quality that linked him to artists such as Katz and David Hockney. His paintings exhibit a lightness of touch and a confidence in their unusual, emotionally charged form sense, and are fearless in their use of vibrant, hallucinatory color, which link him to the aforementioned artists, but at the same time his work has an unavoidable emotional weight and a heavy melancholy. As research for the book continued, more information began to emerge as his career rocketed of, culminating in his first solo exhibition at Karma in 2018, which received overwhelmingly rave reviews, including by the critic Jerry Saltz, who referred to it as “one of the most impressive solo New York debuts I’ve seen in a while.”

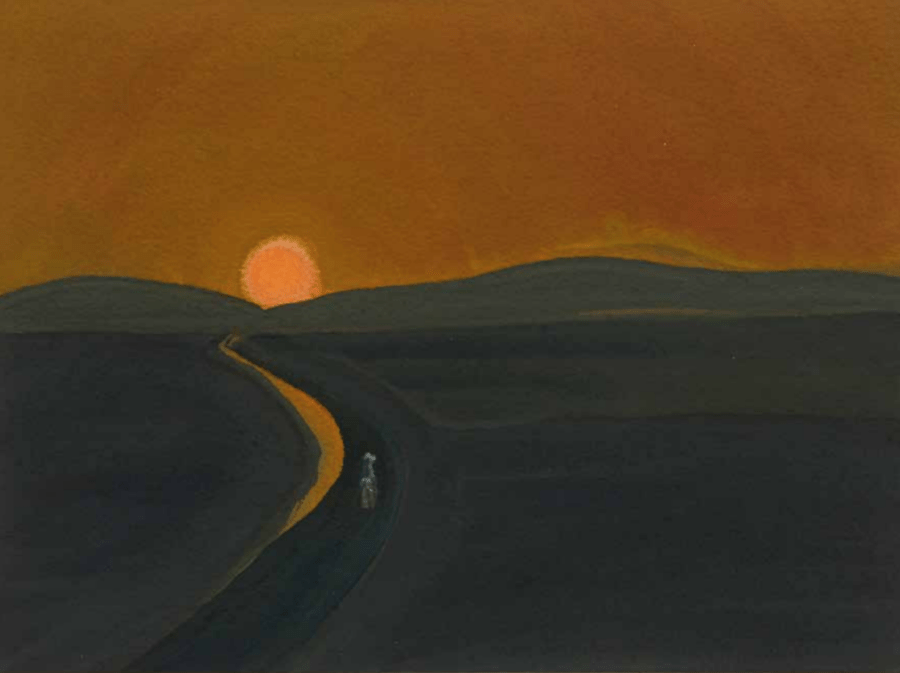

The Postcard paintings had all been made by Matthew Wong in 2019 in preparation for what would eventually become the 2020 exhibition at ARCH. Each work was created using gouache, the opaque watercolor which was clearly well suited to his way of working; the medium can be used with more spontaneity than oil paint but with an increased painterly substance and body than watercolor. As is consistent with much of Wong’s output, each of the dreamlike landscapes depicts a place drawn from the artist’s memories or completely imagined. Viewing these works within the context of the oeuvre Wong left behind, one can see that they are filled with his favored motifs — drifting icebergs, crescent moons, windswept trees, and solitary figures traveling empty paths— and showcase his full toolkit of formal devices, including distorted perspectives, pointillist dabs and dots, radiant washes, and dancing hatch marks.

Although the Postcard paintings related to Wong’s earlier works, witnessing the works in the year of the pandemic lent them extra potency, making them particularly timely as their haunting spirit, their depictions of loneliness and separation, acted as something of a balm for our condition, as well as a corrective to the dominant narratives swirling around Wong’s work in the media’s arts coverage for most of the year. If, like me, you follow the global happenings in the art world closely — or even if you don’t — there is a good chance you encountered at least one headline like these:

“Canadian artist Matthew Wong died too soon last October. His works are now fetching stratospheric sums at auction”

“A Matthew Wong Painting Just Sold at Christie’s for a Record $4.5 Million, Marking a Frenzied Turning Point in the Late Artist’s Market”

“Who is Auction Juggernaut Matthew Wong?”

Normally, I would read such articles with a passing curiosity; they wouldn’t typically elicit a strong feeling either way, perhaps because, for me, they are something more akin to perusing reports on the stock market or scanning the gossip pages of US Weekly. However, this time, these articles brought on a combination of frustration and sad- ness. The earliest of these articles emerged in the spring of 2020, their frequency increasing through the summer as several of Wong’s canvases, including his masterful Realm of Appearances (2018), sold at auction for an astounding seven figures, and then finally culminating in a fervor at the close of the year when River at Dusk (2018) sold for a mind-numbing $4.9 million. When the dust settled, no few- er than twenty-four Wong works (16 paintings, seven works on paper, and a painted book) had sold through the three largest auction houses (Christies, Phillips and Sotheby’s). As the records toppled, the coverage in the media intensified, making it harder to ignore.

Forgotten in all the reporting seemed to be the essence of the artist himself. Each article contained the same recycled biography and the new numbers; reading them left me with a nagging feeling that something was being lost. Perhaps it was because readers were learning about him through this type of financial reporting. More likely it was the grotesque aspect of the speculation happening so quickly after his passing. Looking at social media, it appeared that I was not alone in my reaction. For many who knew Matthew personally or had a deep appreciation of his paintings, these articles resonated with a sensationalism that was unsettling. The problem seemed not to be so much the astronomical prices themselves but the fact that the works were being flipped by collectors so quickly after they were made and acquired. Flipping — the selling of art for a quick profit within five to ten years of a work being made or acquired — has been a hot-button issue in the art world, and according to industry insiders this phenomenon is not considered healthy for the market, especially for emerging artists, as it often corrupts their trajectory.

Of all the commentary on the Wong auction sales, the collector, curator, and writer Kenny Schachter came the closest to describing what I felt when he wrote for The Art Newspaper that what was happening was “morose speculation” within markets that have “no motivations other than opportunism and greed.” The consternation was amplified by the fact that almost none of the reporting discussed the pertinent issues surrounding the flipping of the work, which was leading to the heights that were reached. What was lost were the essential aspects of the artist—his sensitive nature, his innate curiosity, his highly personal yet ambitious approach to making paintings, and his obvious, and deep respect for other artists and art history. Simply put, Wong was at the polar opposite of the machinations and manipulations taking place in the global marketplace.

The landscape paintings of Matthew Wong often depict winding paths, many times with solitary, face-less figures that are usually visible to the viewer, though at times woven into — or entrapped within — his marks. These figures could be read as stand-ins for the artist himself, as the critic John Yau astutely pointed out in Hyper- allergic: “the figures, which disturb the landscape, can be read as surrogates for the artist working his way through the landscape of art.”

Even when there is an absence of figures, the path itself becomes a narrative device; an expression of an inner psychological state that weaves along it. Wong’s 2018 Karma exhibition included a number of path-driven works including The Bright Winding Path (2017), where the picture plane is tilted up, one lone figure making his way up the path flanked on either side by a patterned terrain that brings to mind the graphic language of Yayoi Kusama’s Infnity Net paintings. At other times, as in the haunting Figure in a Night Landscape (2017), figures wander off the path, trapped in a forest of no visible escape.

The winding paths weave their way through many of the Postcard works. In The Gloaming (2019) an empty, pale mauve path meanders through the center, viewed through what appears to be a window framing the landscape on two sides. The heated orange sky radiates behind both the hills and a single tree, with branches that radiate out like veins towards the sky, poignantly capturing the dramatic moment when the sun recedes from sight and night creeps in. In the darkly titled and more naturalistically rendered Going, Going, Gone (2019), a hatted figure, possibly on horseback, lumbers towards a setting sun. The dusty sienna brown landscape recalls that of a Western film, with the lonesome cowboy riding off into the credits.

The path in A Walk by the Sea (2019) is hidden by a shadowy beach in the foreground as two figures in the far distance descend toward a hypnotic orange and yellow-banded sky and a foreboding ocean. With its sense of stillness and warm light, Wong’s work brings to mind the Norwegian Romantic painter Thomas Fernley’s Old Birch Tree at Sognefjord (1839), with its depiction of two figures in the distance viewing a dramatic sunset. However, here the simplicity of the compositional structure and dark void filling the foreground add emotional weight to the journey the travelers are embarking on — unlike the peaceful contemplation in Fernley’s work, one is left with a sense of dread that returning may not be an option.

Diver (2019) contains many of the characteristics of the best of Wong’s works — a dramatic arrangement composed of dynamic dabs and strokes. Although not depicting a path of soil and rock, here a waterfall stands in, dividing the image while lending narrative and compositional force. As in Wayne Thiebaud’s paintings from the 1960s of rocky cliffs, Wong disregards traditional perspective, fattening the visual field leaving the viewer without a clear foothold. The surrounding landscape follows the verticality of the waterfall as if existing on the same plane. A lone figure plunges but is held in stasis three-quarters of the way down, on the verge of falling from our view forever. Like Thiebaud — as well as Jasper Johns and his large-scale drawing Diver (1962-3)—Wong makes gravity a subject of the work; the viewer can’t help but have a somatic response to this depiction of unbreakable free fall. Life and death are held in the balance, the figure not only a proxy for the artist himself but also a simulacrum for all of us who witnessed 2020, frozen in place, temporarily, while, like the diver, suspended on our journeys.