Robert Grosvenor, published by Karma, New York, 2020.

Download as PDF

Robert Grosvenor is available here.

He made it, he said, in his usual plainspoken way, to look at it. For no other reason, simple as that. Not to show it necessarily, although it’s being exhibited now, nor by necessity, because someone had asked him for a work, for a sculpture, an object having that status. “I made it to look at it.” That’s what he said, not too much more. And knowing Bob Grosvenor, you believe him. Unlike some artists, or writers for that matter, he never says anything for effect. He certainly doesn’t need to. His art, outside of a gallery, might not look like art at all, even to the trained eye, so-called. At its most peculiar, in every sense of the word—unusual, eccentric, standing apart, particular, distinct—his art, the things he makes because he wants to see them, may seem to have always been in the world, at times appearing otherworldly. Visionary and vernacular. His work can be both at the same time. Seeing it becomes our vision. He sees things in the everyday that do and don’t seem at all commonplace despite simply being there. Like anyone who walks around with a camera as a matter of course, although Grosvenor is not a photographer in that sense, his eye is attracted to, and his sculpture has been informed by, things he sees in passing—objects, structures, signs, chromatics and their unexpected interaction—that others pass without notice. This accounts for the photos he takes, visual notes, reminders of what’s special in terms of form, proportion and, yes, strangeness. When Grosvenor takes a picture of a hulking black 1940s Ford that has what he describes as “a chopped top” and a visor over its windshield, he’s seeing a vehicle from the past in the present, a past that was looking to the future, at least as car design used to. The artist himself, as anyone in his eighth decade, inhabits a space between then and now, and for Grosvenor (at least as I’d imagine), what about tomorrow? Recollection, presence, anticipation … aren’t these materials for an art. That car holds as much wonder and desire for him now as it would have when he was a young boy. It’s a car he could have encountered at the age of five. Time is a material in itself, matter-of-factly the time required, having put something in the world, to see what it is that you’ve done ands think on it for a while.

What is it that Grosvenor made to reflect upon? This new work of his. He said, “It’s a block of water.” He built it and looked at outside, since he has for a long time had an outdoor studio, a yard really, much different of course from a room with walls and lights and the artificiality of a gallery. It’s there in the yard behind his house that he constructed a rectangular pool with concrete blocks, stacked three high, six wide, twelve in length, having slender concrete blocks along its top edge, holding a liner in place. A black rubber liner inside seals and darkens the pool, the water filled right to the top, creating a glass sheet of sorts, set upon a solid base. Weight and weightlessness. This could be a homemade swimming pool, one you might find improvised for a hot summer day, or pictured in an update of Bernard Rudofsky’s influential Architecture Without Architects, subtitled “An Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture,” published to accompany a MoMA exhibition in 1964, a book which Grosvenor still has. There is a lineage for his work, to be sure, a line he himself has crossed in his own way, from Minimal art in the mid-to-late ’60s—his large hovering “space invaders” from this period are not so minimal at all!—to dense blocks in the ’80s, on to the structures, vehicles, and stage sets, or set pieces, suggesting a theatricality Minimalism never actually had, buoyed by a healthy sense of humor, that followed in the ’90s/2000s and up to now. If there is a forebear for the “block of water” it may well be the artist’s Sphinx-like Untitled 1989/90, not merely for its simple block construction, but as it holds the ground while accounting for and being open to the space beyond. Proportions are important to Grosvenor, and these two works are reciprocal in “footprint,” while the earlier work’s skylit, corrugated roof recalls the corrugated fence that can be seen, thirty years later, behind his “block of water,” as it was originally situated and photographed in his studio/yard.

Architecture without Architects by Bernard Rudofsky

When we think of a block of water we may imagine an oversized cube of ice, water only being solid when it’s frozen, and not guaranteed for long. A tray of ice cubes in the freezer will eventually evaporate. And in art? Allan Kaprow’s Fluids, realized in California in the fall 1967, comes readily to mind. For this happening, Kaprow and a group of volunteers built large ice houses, as he stated: “During three days about twenty rectangular enclosures of ice blocks (measuring about 30 feet long, 10 wide and 8 high) are built throughout the city, their walls are unbroken. They are left to melt.” Blocks of ice, solid and ephemeral, will only last so long, especially under the California sun. Concrete blocks last longer. Made of concrete and coal cinders, produced in standardized rectangular units, with a double hollow center, they are easily stackable. A single block already suggests its potential. This “primary structure,” to borrow the term from Minimalism, offers inexpensive construction which doesn’t require, as Kaprow’s volunteers proved, any particular training. One on top of another, with one turned sideways to make a corner—architecture without architects—and four corners make an enclosure. There was nothing inside Kaprow’s ice house, and no roof. Inside Grosvenor’s: water. A low enclosure of water, a pool, something the artist wanted to look at: a reflecting pool. In some sense all Grosvenor’s works, involving work and play, even before they become art—if they ever do—function in this way for him, something to contemplate, the product of his eye, his mind and his hands, before they are seen by us, in a gallery, as artwork. In the space between the art yard and the white cube we have before us something to contemplate, not an object in itself (it is that, certainly), but the key question raised over a century ago, and more relevant now than ever: “Can one make a work that is not a work of art?”

Robert Grosvenor, Untitled, 1989–90.

Fluids, a Happening by Allan Kaprow, 1967. Photo: Dennis Hopper

In this respect, even unanswered, maybe it doesn’t matter if Grosvenor’s block of water is or isn’t a work of art (though now designated as such). He made it to look at, and now he shares it with us. It is in and of the world. In a gallery it is a container contained. And still, as still as the water full to the top, something may happen. We the viewers circulate around it, look in and see ourselves reflected, will see one another. Even before encountering it in the gallery—anticipation may be part of art’s subject, for the artist as well as the audience—I’m reminded of Robert Barry’s Marcuse Piece, 1970-present: A place to which we can come and for a while “be free to think about what we are going to do.” Grosvenor’s art yard is just such a place. He saw his block of water outside once it was built. Looking at this work which was not yet a work, he would have seen the sky reflected in the water, seen the wind ripple its surface. In the fall there could have been leaves afloat on the water. Birds likely flew by and visited now and then. Outside it merged with its environment. Inside, there is no such overlay, the contrast too high, no softness to the light, no wind to gently bend the mirror reflection, no birds or sky above, only water. The structure, very simply put together, a pedestal of sorts, a liquid sheet, a stage of glass. And then there’s us. The gallery a place to which we come, and for what? The great conceptual piece of Barry’s, though having a fixed point of appearance, extends to a distant horizon, into the future, engaging temporality and pure potentiality. Whatever happens is up to us. As the artist steps aside, rather than a work for observers to “complete,” something has been proposed. This is key to its openness, to its offering an emancipatory space.

The quote from Herbert Marcuse comes from his landmark 1969 text, An Essay on Liberation. The late ’60s, which Grosvenor’s generation passed through, at times uneasily, at times excitedly, was a period of restless curiosity, a time when one sought room to breathe, to move, and raised fundamental questions. What else can art be? And what else, as human beings, can we be? Although the question “Can one make a work that is not a work of art?” was posed by Duchamp in 1913, it’s as much from the past as it’s relevant to where we are now, a world where anything, for better and for worse, can be considered art, as if it was impolite to say it wasn’t! This, in part, is his fault, though he couldn’t have anticipated what would follow, and may have claimed indifference to his followers. (Well, nobody’s perfect.) Today we see pictures on the wall, one after another, retinal in every sense of the word, framed—for a crime committed?—at the service of the eye more so than the mind. Of course it’s art. Of this there can be no disagreement. But who wants to live in a world where art doesn’t exist, at least now and then, past and present, for argument’s sake? To make a work that is not a work of art: having gotten that much easier has made it, conversely, that much harder. Art has arrived at a destination of, when it may have become a point of departure from, normality. Where, we might ask, is the strangeness? In all this we may have gone, as it’s said, “off the deep end,” even though Grosvenor’s block of water has none. Therein lies its depth. Its potential for reflection. A place to which we can come … for a while. Grosvenor presents an object-situation, situates an object in a supposedly neutral space, allowing for a concentration on what’s right in front of us, but what is it exactly? As we allow ourselves to be pleasurably lost (if we do), the mind is bound to wander.

Art Is a Vehicle For Ideas

Strangeness in the work of Grosvenor is often, in a sense, afoot, buoyed by humor. Consider the photo of his “clown shoes.” Made of construction paper, sprayed brown, loosely laced, two to three times usual size, topped by a pair of cuffed canvas pants seen from the knees down. A figure stands before a car, of which a single tire appears, a Goodyear Wrangler. In a second photo taken on the same spot, the shoes alone. Disembodied, they are no less comical. The artist disappears. (Remember that movie, The Invisible Man?) Faced with the figure/ground problem we vote with our feet. This pair of shoes, we’ve been told, no longer exist. Unreliable vehicles for escape, they would have fallen apart in any case. Ephemeral props for his own amusement, laughter a form of liftoff, to hover upon the everyday and glide, flying with your feet on the ground, head in the air. “I’ve got this hobby,” Grosvenor has said, “making things: boats and cars. Until recently I’ve always kept them at a recreational level, just having fun.”1 Some of these boats and cars, not forgetting a scooter on occasion, and things unclassifiable, have appeared in galleries, sailed in as it were, reminding us that art—even that of a hobbyist with a highly attuned feel for proportion, volume, color, finish, dynamics, and aerodynamics—is a vehicle for ideas. The vehicles themselves may not have been particularly loved or estheticized in their original state. We can think of them, once Grosvenor has made his subtle alterations, as assisted readymades. The claiming of them for art (old habits die hard, and art, as we know, is habit-forming) also has to acknowledge that cars have always been modified, “souped-up,” made faster and in the process made strange. The cars Grosvenor photographed long ago on the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, equally familiar and alien, before us and simultaneously not of this world, seen in an otherworldly landscape, suggest velocity even at a rest. One long black tapered vehicle is a stealth torpedo of sorts, an object of fascination and danger, an object-vector propelled through time and space. In its presence, this vehicle inhabits the past and the future, futuristic and Medieval, its plating a suit of armor, a toy model life-size.

Grosvenor’s Three car unit, 2012-2017, has very much this feel of expansive toys, models scaled up to human size without losing their Lilliputian character. As Grosvenor describes his attraction to them and their forming a triptych:

“I’ve always loved the Daf, the Solyto, and the Renault, which is to the right. Nobody particularly likes that car, but I like it, and I thought maybe I can make it a little better by doing this and that. Maybe I could make it interesting. I always wanted to put a fin on the back of that car, which I did. And then the car in the middle, which is just such an eccentric thing, you know, it just had to go in the middle. Then the car on the left, the Daf, is a Dutch car that nobody ever liked. But I always sort of thought it was cool in a way. So I smoothed it out a little bit and I felt that they looked good together, the three.”2

Robert Grosvenor, Untitled, 2014–17.

Robert Grosvenor, Untitled, 2014–17.

His initial presentation of them, side-by-side in a space barely wide enough, created a situation in which front and back views were distinct, calling attention to their individual double-nature, in terms of what was original and what had been done to them, and their triple identity, a camaraderie, one for all and all for one. With only a narrow space in between, the viewer is in close proximity when going between, encouraged to look closely, peering inside. The bug-like New Map Solyto, a French three-wheeled utility truck from the ’50s (max speed: 30 miles per hour), with its visor windshield and skeletal peeled back dome, could be a surveillance car, meant to fly below the radar. This microcar makes for a funny fulcrum in Grosvenor’s triptych, though sensibly functioning for symmetry of scale and chromatics. While the squat Daf is painted uniformly from the hood to the trunk, the curved Renault is two-tone, as if an outer shell was pulled up from the back bumper to the roof’s midpoint, covering the rear window, and emphasizing the trunk’s vents, which appear as gills for an amphibious-seeming cvehicle. The headlights and taillights of the Daf and the Renault were modeled over and painted, along with their front grilles. Whether parked inside or out—and in the gallery they recall a ship in a bottle—these cars don’t fail to startle and delight, and if we ask What’s wrong with this picture?, the answer would be, straight-faced, minds smiling inwardly, Nothing at all.

Robert Grosvenor, Untitled, 2014.

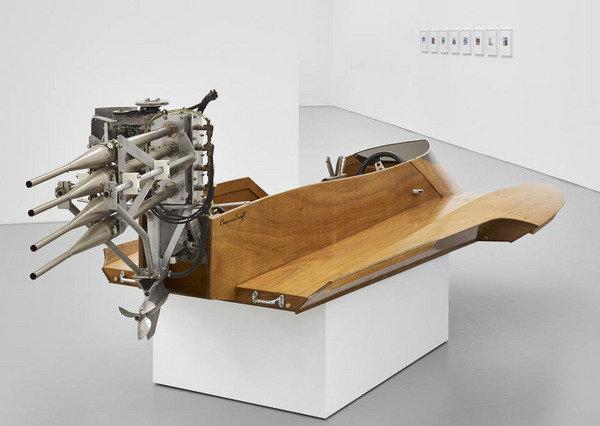

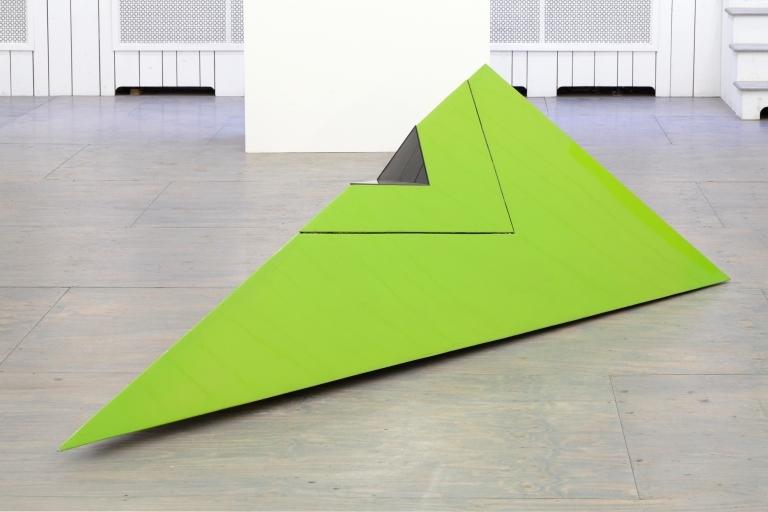

In the midst of Grosvenor’s three cars occupying his imagination, a period of no less than six years, his hobbyist tendencies turned to a monster engine and a sleek speedboat which, brought together, would become Untitled, 2014. A boat that might have roared across the Salt Flats when it was submerged as ancient Lake Bonneville some 20,000 years ago, this is an utterly fantastic object, like nothing we’ve seen before. Its raised motor resembles a gnarly, deadly weapon, in distinct contrast to the soft tones of its wood body and surfboard-like wings. That same year, Grosvenor built Aerocar, an asymmetrical triangular chassis of painted aluminum set on three wheels, one at its front tip, with a high-mounted engine, a wood propeller, and a basic, some might say precarious, seat frame. The 2014 Aerocar has a predecessor in a vehicle with a similar chassis, though symmetrical, cloaked by an acid green pyramidal hood, dating from 1965. With his speedboat, the car trio, and these two Aerocars as our points of reference, we have a reciprocal lens through which to view an array of 30-plus model/prototypes Grosvenor collected over a period of fifteen years, being shown for the first time, and as a single work. These include boats, cars, airplanes, a helicopter, what appears to be a small propeller-driven bomb, dolphin-like “missiles,” and hybrids—one plane has a tower structure more commonly seen on the dorsal deck of a submarine—and an elegantly elongated form in wood that can be seen as a horizontal Brancusi Bird In Space. Ranging in size from miniature to more than two feet long, most can be held in the hand. They are primarily lightweight. A child could play with them. The temptation would be hard to resist. None belonged to Grosvenor as a child, and he didn’t build models in his youth. (Two tin metal racers, produced by Penco in 1947, when he was ten, are possibly the earliest objects in the collection.) With the artist’s vehicle sculpture from the mid-’60s to now, it’s understandable to suspect he may have made modifications to these objects, sly and imperceptible, close to his sense of humor and sensibility, but he did not. They are all exactly as he found them over the years, “mostly in flea markets, occasionally at a yard sale.”3 If in them there is for us a connection to his art, their partocular characteristics and personalties must be what attracted him to them in the first place.

Robert Grosvenor, 3 Wheeled Car, 1969

When asked if he had added the two round clear rotors on the helicopter, he insists this is exactly how it originally was. When asked if he hadn’t in fact painted black the dome, patterned with beautiful hairline cracking, on a UFO-type three-wheeled car, he again demurs, and you have no reason to believe otherwise. Yet another black painted dome tops a sleek car, a design model, with a lustrous golden-bronze metallic finish, and no wheels, a sort of hovercraft afloat on a low pedestal with a plaque inscribed: To Our Friend Dick Thornton—Opel Styling 11 July 1972. Nearly thirty years later it finds itself in Grosvenor’s “motor pool” alongside a small pod-like craft that sits atop a copy of the book, Raketen Fahrt (Rocket Ride), from 1928. Its author, Max Valier, was an Austrian rocketry pioneer whose work would prove crucial for engineers in the aerospace industry long after his early death, caused when a volatile jet fuel formula he was developing blew up in his lab.

Max Valier, 1929.

The illustrations on the book’s cover, a wide-winged plane and a turbocharged car, have much in common with this assembly of Grosvenor’s, quite possibly their proto-prototypes, and resonate with the vehicles of his own design. The Valier car’s four exhaust pipes (though likely eight, with four on each side, aligned from beneath its chassis), appear revved up at full throttle, and can be related to those on the monster engine powering Grosvenor’s 2014 speedboat. In all this a sort of time travel is suggested. 1928 … 1972 … 2014. From Max Valier to Dick Thornton to Bob Grosvenor, a line can be traced in our mind’s eye between their idea-vehicles, between advanced engineering and inventive bricolage, making often done with whatever’s at hand, marked by abundant curiosity, the fuel that powers imagination.

Robert Grosvenor, Aerocar, 2014.

Returning to the block of water, mirror-like, tranquil, liquid and solid, open and contained, one of the objects in Grosvenor’s collection is recalled: a glass-bottom boat, an early example of the kind you find from Key West to Hawaii to the Great Barrier Reef. Grosvenor, who spent many winters in the Florida Keys, and has for years lived on Long Island, on the Atlantic’s Great South Bay, has been near the water for much of his life, close to a distant horizon. What would be visible beneath that glass bottom boat as it buoyantly anchors the surface of his reflecting pool? With its black liner, its depth is elusive, though only a few feet away. Immediately before us on a cold January afternoon, this indoor pool allows us to reflect on an object brought outside in. On a below freezing day, outdoors, it would be icily glassed over. In the gallery, where we experience art at room temperature, our eyes swim in its warmth, while above and below the surface all its simple mysteries remain.

Published on the occasion of the exhibitions at

Karma

188 E 2nd Street

New York, NY 10009

January 8–February 23, 2020

Galerie Max Hetzler

57, rue du Temple

75004 Paris

January 18–March 14, 2020