Alex Da Corte, Marigolds, published by Karma, New York, 2019.

Download as PDF

Marigolds is available here

Mason Williams explained why. By his own admission, the songwriter and musician ordinarily wrote poems, one of which can be found in the liner notes of Stay Awhile, the 1965 album by American folk band the Kingston Trio:

Through the window

The wind bends

The green-tassel tree

The gray bay waters lay

At the bottom of the day

The lumpy-hump hill

Is very still,

As not to dislodge

Its hodgepodge of lodgings

The double-silver sky

Completes the why

There’s a window

Two years later, in 1967, Williams had an idea for a film. Having moved from Oklahoma to Los Angeles with his childhood friend Ed Ruscha, with whom he would collaborate on artists’ books documenting their improvised “capers” such as throwing a typewriter out of a car, Williams wanted to make a film documenting his plan to “draw the world’s biggest sunflower.” Just after sunrise on the morning of July 11, he hired a skywriter and cameraman to accompany him to the California desert. For about forty seconds, if you looked up, you could see the bloom across the bright blue sky.

***

Robert Gober explains how. In an introduction to the artist’s 1993 exhibition at the Dia Foundation, Karen Marta noted that the notoriously reticent conceptual artist, when willing to discuss his art at all, would “explain the facts of the way something works . . . the mechanism behind it and the mistakes he made before perfecting it,” but “never reveal the impulse of what led to its creation—his own interior life.” For their part, critics and art historians have pointed to Gober’s Catholic upbringing, the AIDS crisis, the art of surrealists like Magritte, and the delicate shadow boxes of Joseph Cornell as a diverse array of the artist’s influences. Together they form a trail of references that lead to the protruding limbs, floating sinks, green apples, and candles—each carefully molded by hand from beeswax, plaster, and other materials— that define Gober’s visual lexicon. His métier is the intimate gesture, a seduction of the viewer achieved by the rigid estrangement of the familiar. Sexuality, spirituality, symbolism: one peers into the universe of Gober through the portals demarcated across his oeuvre, through cellar doors and drains.

Or through windows. Windows appear variously in Gober’s drawings, lithographs, and installations, such as the installation Prison Window (1992). Like the crib sculptures that preceded it, Prison Window suggests both a physical and psychological entrapment. Set high into the wall, transforming the gallery space into a prison cell, the barred gates of the window stage the illusion of an exterior world beyond its frame— outside is that same bright blue sky. Placed definitively out of reach, Gober’s prison window offers the viewer a false promise of escape.

***

For the past decade and counting, Alex Da Corte has created videos, installations, and environments that articulate his engagement with our present conditions: the resolute grip of late capitalism and its attendant world of consumer goods, the psychological impacts of repressed desire, and the potential for shared experiences across networks of people and objects. Freewheeling across the aesthetic cues of pop and post-Internet, Da Corte eschews the droll and the ironic detachment of his predecessors and peers, pressing instead toward the moments that yield transformation.

An artist’s artist in the truest sense, Da Corte frequently incorporates others’ works in his own assemblages to reinvigorate the possibility for various, simultaneous, and contradictory readings of the constituent objects and resultant tableaux. He appropriates others so as to expand the horizon of potential for all parties involved. If Gober attunes himself to the possibilities afforded by defamiliarization and perversion, Da Corte draws from these same lineages and reassembles their sensibilities in a signature détournement. For the 2015 exhibition Die Hexe at Luxembourg & Dayan, Da Corte placed Robert Gober’s chrome-plated bronze drain, Untitled (1993), in a mirrored broom closet, visible only through a hole in the closet door. A 2013 installation made in collaboration with Borna Sammak, As Is Wet Hoagie, existed for the first month of its run as the locked storefront of the East Village gallery Oko, from which viewers could see the neon lettering and assorted ephemera of two other storefronts. Referencing the Philadelphia storefronts familiar to both Da Corte and Sammak, the installation reads alternatively as mirrors mirroring one another, as frames framing other frames, or as a window looking into other windows.

The mirror, the frame, and, critically, the window, have each been deployed as metaphors to describe the function of the art object, defining the limits and potentials of its engagement with viewers and with society at large. For his 2018 exhibition C-A-T Spells Murder at Karma, Da Corte fixated on the open window, drawing inspiration from R.L. Stine and Alfred Hitchcock to examine the unlocked window as the locus of fear. Six wall-mounted installations in neon with vinyl siding depicted open windows, beckoning (with a pie on the sill) or ominous (boarded up, or with a billowing curtain), their domestic facades a Goberesque nod to the sinister potentials of the home. Here, by virtue of its open state, Da Corte’s window functions as promise, and simultaneously, as threat.

***

Technically speaking, there are no windows in Marigolds. Technically speaking, there are drawings, sculptures, and paintings, the subjects of which trace back to more than half a century of American cultural production, comics and cartoons created during the latter half of the twentieth century. The exhibition takes its title from the eponymous 1969 short story by Eugenia Collier, set during the brutal years of the Great Depression in rural Maryland. Told from the perspective of its protagonist, Lizabeth, the story recounts the moments of a summer that “marked the end of innocence” and “the beginning of compassion.” At fourteen, Lizabeth sees herself on the precipice between childlike innocence and the nascent recognition of adulthood, cognizant of the ravages of poverty upon her family and community. She and her friends amuse themselves by taunting Miss Lottie, the town eccentric deemed a “witch” by the children. Miss Lottie’s attentions are fixated on her titular plot of marigolds, whose “bright blossoms, clumped together in enormous mounds” disrupt the “perfect ugliness of the place; they were too beautiful . . . they did not make sense.”One night, after overhearing her father sob in despair over his inability to provide for the family, Lizabeth can no longer hold inside her frustrations—at her economic circumstances–or the confusion of youth. In the dead of night, she climbs out of her bedroom window toward Miss Lottie’s yard and in a fit of rage, tears Miss Lottie’s marigolds from the ground. In the midst of the violent act, Lizabeth is caught. She looks up to see the woman she once considered a witch, now merely “a broken old woman who had dared to create beauty in the midst of ugliness and sterility.” Heralding the end of her childhood, the encounter with Miss Lottie prompts Lizabeth to look beyond herself and gaze into the lived experience of other people.

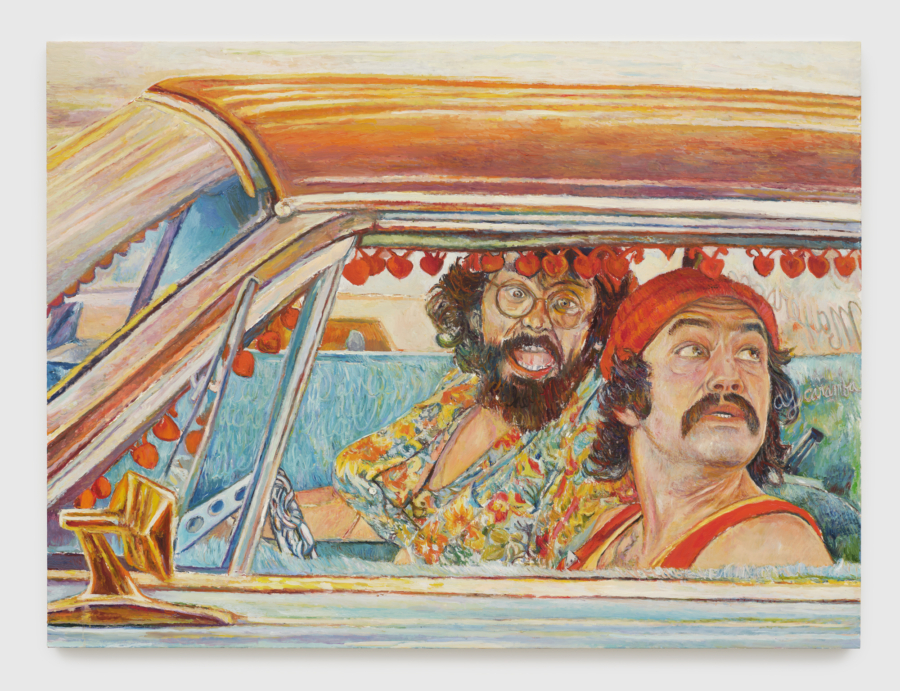

Chief among the many resonances between Collier’s short story and Da Corte’s visual art is Da Corte’s empathetic recognition of the alienation and loneliness caused by difference. Throughout his oeuvre, the witch—historically maligned and placed at a remove from society, and whose isolation is reinforced in children’s tales—is repurposed as a sympathetic figure. By skillfully and selectively deploying elements of entertainment usually demarcated for children (such as cartoon and comic book characters, garish colors, and geometric shapes), Da Corte taps into the same amalgamation of confusion and fear that Collier so evocatively illustrates through her use of a child’s perspective.

Yet, Da Corte’s gamut is neither faux-naïf nor cynical. Rejecting the scathing irony toward advertising that the pop artists weaponized in their scavenging of comics and cartoons for their art, Da Corte instead considers how cartoons, comics, and animations transgress moral and social codes, abstracting and subtly reinforcing violence and sexuality. Recent scholarship on the history of animation by the late Hannah Frank suggests that the single animated frame—which originated from the photographic image—was the vanguard of artistic and cinematic innovation, prefiguring a number of developments in sequencing and technology later utilized by artists and filmmakers. The photograph, argues Frank are “centrifugal, pushing us outward beyond its bounds: a window”; considering animation as photography allows us, Frank suggests, “to find the world that has been cropped out of the frame,” a subversion of André Bazin’s famous dictum that film is a “window to the world.”

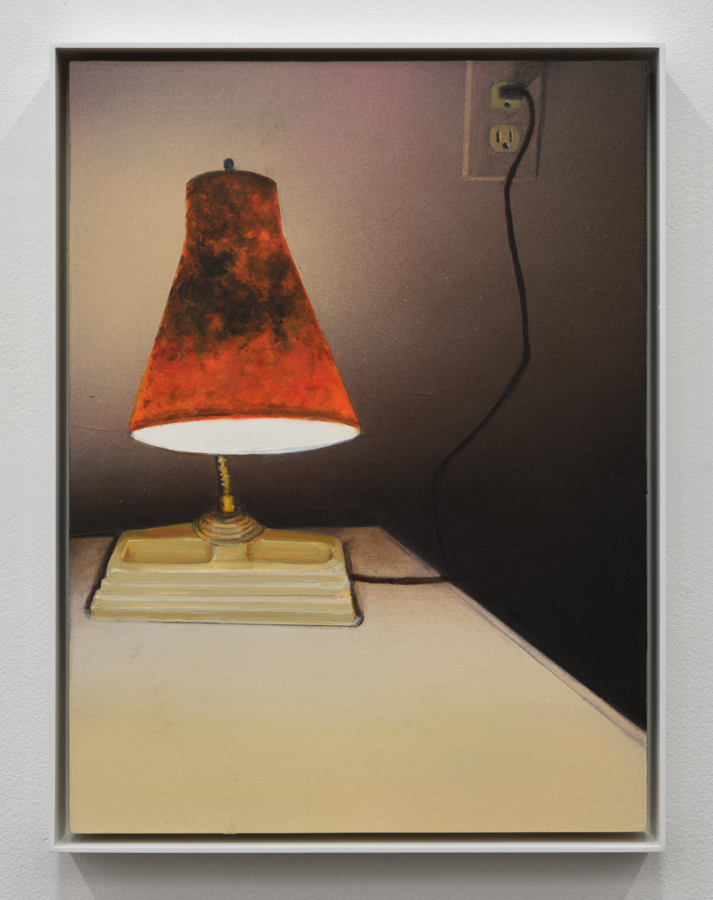

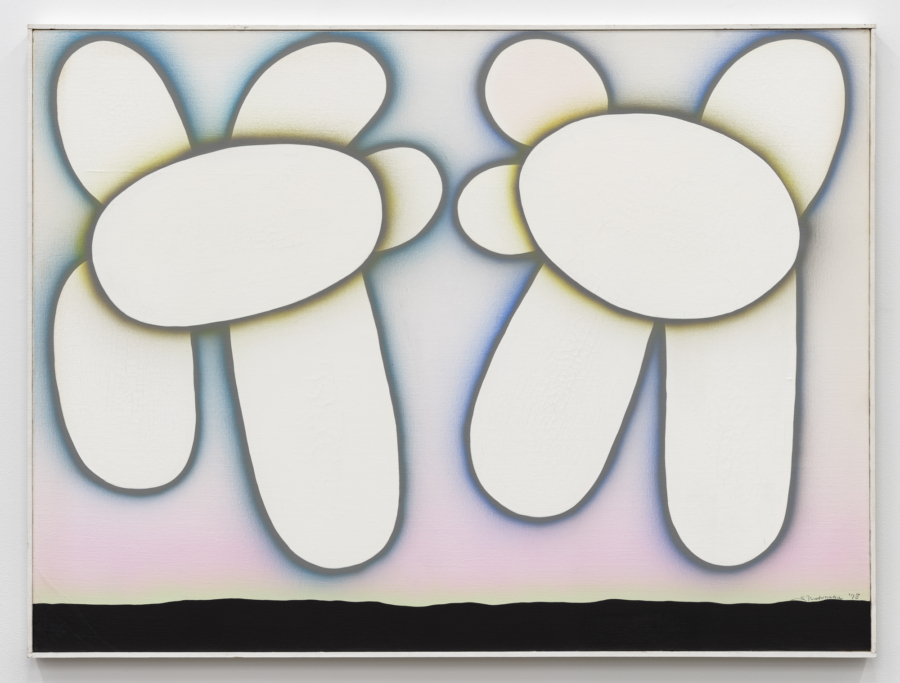

Da Corte, who studied animation as an undergraduate, deftly adapts these arguments in a series of large-scale wall-mounted works, evincing that if, in the context of animation, windows conceal as much as they reveal, an effective strategy for focusing our vision is to apply animation’s implications of movement onto still objects. Constructed from foam and wrapped in neoprene, these sculptures each correspond to a blue pencil erasure drawing from a vintage comic book; seen together, they elucidate the artist’s process of carefully selecting, editing, and decontextualizing cultural touchstones from Disney, Warner Bros., Hanna

Barbera and other production companies. The Pied Piper (all works 2019) depicts a pair of disembodied hands playing a pipe fashioned from a carrot, referencing the fairytale popularized by the Brothers Grimm in which the titular musician leads away the rats of Hamelin with his magic pipe. When the townspeople refuse to pay the piper, he steals their children. The fairytale, which is also the subject of a sculpture by Paul Thek (The Personal Effects of the Pied Piper [1975–6]), reinforces the sinister undertones of stories intended for children, corresponding to Da Corte’s signature ethos.

Mounted on the white walls of the gallery, the distended images—among them a candle, a broken jack-’o-lantern, a lamp and paint bucket—appear to float, as if set in motion, a sensation enhanced by their position above the floor, which has been tiled cyber yellow, evoking the neon glow that has often functioned as a backdrop to Da Corte’s installation and manifests his fluid understanding of analog and digital technology. Though they appear flattened or two-dimensional, the sculptures shift according to the viewer’s perspective, appearing larger, revealing their depth as the viewer approaches. Despite their graphic appearance, the dynamism of these sculptures lends them a kinetic quality, recalling Sergei Eisenstein’s commentary that Disney’s animations “have the habit of stretching and shrinking, of mocking their own form.” Isolated from their comic book and cartoon contexts and transmogrified from image to sculpture, these sculptures also invoke a sense of mutability. Their morphology of form and function shares an affinity with the surrealistic animated imagery of Suzan Pitt’s handmade film Asparagus (1979), in which the titular vegetable warps across contexts and images, each frame a new way of envisioning the asparagus’s purpose. Da Corte’s attentiveness to the legacy of animation, his appropriation of its humor and transgressive potential, and his awareness of animation’s formal inventiveness give his practice its nimble, fluid mark. This is the sly and slicing efficacy of Da Corte’s art: in his perversion of pop, the artist indicts the slick aesthetics that has given neo-pop art its market appeal, while also demonstrating the potential and possibilities these styles afford.

Thematically, Marigolds tracks Da Corte’s recurring obsessions: how fantasy, in its various forms, sits at the edge of violence and escapism; how dreams can offer freedom without restrictions or conditions; and how, in private and intimate moments, the freedom of dreams seeps into reality. Accordingly, Da Corte has negotiated the division between exterior and interior states in the exhibition’s presentation. On the exterior wall near the gallery’s entrance, the artist has enlarged a photograph, Weapon X (… On The Stove Bench), of his nephew asleep in the front seat of a car, bathed in lurid green light and half-obscured by shadows. He is held in place by a seat belt, which divides the composition of the photograph diagonally, mirroring the divide between physical reality and its oneiric counterpart. Physically constrained in the seat, the sleeping child occupies both worlds, but in his dreams—invisible and inaccessible to the viewer—he is without bounds. Yet, in his empathetic documentation of this tender and intimate moment, Da Corte suggests that the viewer can imagine the wonder within the child’s mind—that it is possible to share this moment of possibility.

It is no accident that lens-based mediums such as photography and film are subject to the strongest associations with the window and the frame, the latter term designating the single complete picture within a film, video, television show, and comic strip. Consider the evocative staged photographs in Bruce Charlesworth’s series Trouble, made in 1982–3. For these photographs, Charlesworth asked his subjects to improvise their poses. The resulting images feature blurred figures in the thick of action: in #7 from the series, a man appears to be falling out of a window. Charlesworth doubles the pictorial frame, first in the bounds of the image itself, then through the mint green frame of the window frame from which the falling figure emerges. Inside that frame is complete darkness: the window only leads to a hole, an absence. Here, the window is a means of escape.

Escapism has long been associated with fantasy, but in the characteristic machinations of Alex Da Corte, this impulse is treated cautiously, not taken at face value. In the gallery’s back room is the sculpture A Husband Pillow (2019), a three-dimensional rendering in foam, polyfill, and upholstered corduroy of “Drawing Number One”—a boa constrictor digesting an elephant—from Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s Little Prince, a novella-length endorsement of the necessity of imagination. At the start of the book, the narrator recounts creating Drawing Number One when he was a child and showing his creation to adults, who merely saw a man’s hat rather than the fantastical engorged snake. Disappointed by the adults’ inability to understand his art and their insistence that he focus on “practical” subjects like grammar and arithmetic, the narrator abandons “what might have been a magnificent career as a painter.” Drawing Number One becomes a Wittgensteinian duck-rabbit, a Rorschach test for the narrator to identify those who, as a consequence of growing up, had lost their ability to imagine. By taking this fantastical premise from a well-trod, perhaps even hokey story and giving it a precise form, Da Corte reinvigorates The Little Prince’s lesson for our contemporary time, shaping fantasy into potential. If, in a world defined by rampant injustice and increasing inequality, it is possible to retain any degree of aspiration, any semblance of hope, it is contained within the prudential belief in alternative ways of seeing reality.

Through the Da Corte calls for isn’t a blind optimism, but a clarity in perspective, a position he articulates most effectively in the painting Soup of Letters (In the Night I Climbed Out Of The Window Towards The Ground But Never Got There) (2019). The title refers to the term for word searches in Spanish; its parenthetical subtitle alludes to a dream the artist once had, a free-falling vision of unbounded possibility. The painting’s primary color palette and geometric form are immediately compelling, but it is upon close looking that the painting reveals itself to be the coda of this exhibition. To unlock the visual and spiritual potential within this painting, the viewer must suspend disbelief, must shed the blithe indifference and calculated antipathy so tacitly endorsed by contemporary society. The painting is an invitation. It is a way of realizing new ways to relate to one another, new means to relate to the world around us.

There is a window: Da Corte has opened it.