October 2, 2019

Louise Fishman: My City

Locks Gallery, Philadelphia, 2019.

One evening in the early 1960s, around midnight, Fishman boarded a Greyhound Trailways bus from her hometown of Philadelphia up to New York for a couple days, to see art and hang out in the city’s underground gay bars—usual stuff. She hopped onto a nearly empty bus and recognized the sole fellow passenger, the singer Nina Simone. Fishman had been listening to Simone’s newly released debut record and had seen her perform several times in Philadelphia’s jazz clubs.

Fishman asked to take a seat next to her. “She and I both knew that nobody else was on the bus, so I could have sat anywhere,” Fishman remembers. “The conversation lasted the whole bus ride. I said I was a painter and that I loved her music, particularly her piano playing.” She told Fishman she sang to make a living but was truly an aspiring concert pianist. Simone had been denied admission to Philadelphia’s Curtis School of Music, probably because she was black. As they parted ways, Simone encouraged Fishman to continue to come see her in the bars, a more intimate setting, and not to bother with the concert halls.

Simone’s Little Girl Blue (1958) had been circling the turntables of Fishman and her friends, who were “nuts” about her propensity to break into classical piano fugues and mix them in with her jazz songs, like on the opening track, Duke Ellington’s “Mood Indigo,” where Simone laments in her iconic androgynous, undulating baritone: “You ain’t never been blue / Till you’ve had that mood indigo.” Fishman knows something about the blues.

Over the course of the past few weeks, I have gotten a better glimpse into the work and life of Louise Fishman through a series of conversations with her. She is a riveting storyteller and recounts—with great fervor and pride—her Jewish parents’ immigration, her involvement with the women’s and gay liberation movements, and historical shifts in the art world during her fifty- plus year career.

After high school, Fishman moved to Center City from her parents’ place in Havertown in the next logical stage of her coming of age, where she was proofreading and editing at publication houses to make a meager living while exploring her passion: painting. Fishman was in and out of art schools, passing through the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the Philadelphia College of Art (where an affair with a female teacher halted her studies there), and attending Tyler School of Fine Arts two separate times before earning her degree. She was a headstrong outsider, a lesbian Jewish painter, constantly at odds with the idea of formal arts education. “I’ve quit every art school I went to after a year because I couldn’t stand it. I would say to myself, ‘I don’t need these schools, I can paint on my own.’”

Fishman had early exposure to the arts through her mother, Gertrude Fisher- Fishman, who introduced her to important influences through Philadelphia’s great institutions: among them Soutine, Cézanne, Matisse, and de Chirico at the Barnes Foundation; Mondrian, Duchamp, and van der Weyden at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Fisher-Fishman was a painter who took classes with Violette de Mazia at

the Barnes and frequented the Print Club. She would drag young Louise along on her outings to the city, where they often ended up at the Gilded Cage coffeehouse downtown, a bohemian haven where artists, writers, and intellectuals would commune and sip Earl Grey. During a life drawing session at the Print Club, the instructor handed her a board, pencil, and newsprint and invited her to participate. She sketched the nude model and wowed everyone with her talent, including herself, but she remembers her mother’s jealous reluctance to praise her. “She was furious,” she says.

Her father’s sister, Razel Kapustin, was a social realist painter and communist who studied with Siqueiros. Kapustin lived in Center City and showed widely, lectured, and taught classes at the Young Men’s Hebrew Assocation on Broad Street. Fishman proudly maintains Kapustin was the first woman in Philadelphia to wear pants around town, and she remembers her aunt slipping a copy of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex to her mother. Kapustin never had children of her own, so she doted on young Louise and was no doubt an important feminist and artistic influence.

After Tyler, Fishman completed an MFA program at the University of Illinois, Urbana- Champaign, and then headed directly to New York in 1965. Abstract Expressionism was the dominant mode in art, and the women’s and gay movements were gathering steam. A picture of her from around the time shows a hipster with striped tee, heavy- looking masculine rings on her fingers, leg slung over a sawhorse, and a headful of thick loose curls: a tough but tender tomboy with no small resemblance to Bob Dylan. Fishman became involved in Redstockings, joined a chapter of W.I.T.C.H. (the Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell), and was one of the editors of the important lesbian issue of the feminist journal Heresies. She was an activist and kept company with queer writers and academics on the forefront of the movement.

During this time in the 1970s, her mostly geometric practice was reworked as she experimented with cutting up and sewing her paintings back together. She says it was her attempt to create an art not based on male influence, although she confirms she never particularly liked or identified with this exploration of women’s work. She never abandoned the grid, and her output from this period is stunning, beautiful because it embodies an awkward masculinity that demarcates it from otherwise similar contemporary work by women. Fishman sometimes used staples haphazardly instead of needle and thread, in a butch move that reveals her frustration with techniques that didn’t suit her. She favored rough knotting and tools like a rivet gun over knitting and sewing. The work’s character is closer to Joseph Beuys than Eva Hesse (although Hesse was among her friends)Untitled, from 1971, for example, is a cut and reassembled painting of heavy canvas squares painted densely black, hung roughly with grommets, frayed at the edges and brutish, overall.

She then changed course completely in 1973, “dropping everything,” she says, to focus solely on the straightforward, feminist Angry Paintings. In this text-based series, she has scrawled “Angry Louise,” “Angry Marilyn,” “Angry Paula” (Cooper), “Angry Gertrude” (her mother), etc. across 26 × 40 inch rectangles. There are thirty of these in all, in which Fishman’s rage is spelled out as she positions herself within a politics of feminism. Even though she ultimately returns to her highly individualized gestural play within a loosely gridded rectangle, this feminist, queer rage never completely leaves the work. She maintains a toughness and individuality after the Angry Paintings series that is in many ways in synch with the overtly masculinized Abstract Expressionists with whom she is often compared, but from whom she is rightly distinguished. Helaine Posner, the curator of Fishman’s first retrospective, at the Neuberger Museum, describes her singular contribution:

Both embracing and redefining the aggressively masculine tradition of Abstract Expressionism, she has employed its formal language to create large-scale, gestural abstractions that share the physicality, dynamism, and emotional force of that movement while remaining visually poetic and intimate in tone.

Fishman counts these male painters (Kline, de Kooning, Held) as undeniably important influences. She had also been paying close attention to the work of Joan Mitchell, her contemporary, but, of course, there were very few other women. Fishman replays the masculinity of her forerunners in abstraction, but cuts through to its underside, its layered messiness. She denies the delicacy of the sort of painting that masks its construction. She turns the gestural painting inside out and exposes its guts on a monumental scale. Her experiences and emotions are spread across the canvases: messy but structured, constrained but unironically expressive. Her work is deep and tough, often a palimpsest of reworked, sanded, roughly applied paint that conceals in buried layers as much as it reveals in décollage. One of her signature moves is chipping away globs of dried paint to reveal underlying color. She sands and blurs, reworks long singular strokes, applies globs, and shovels the viscous oil paint around with oversized work tools: serrated trowels, large scrapers, and the occasional finger or whole hand.

She rages within the rectangle, pushing and pulling along the confines of the grid and rectangle, exposing its limitations. In Coda di Rospo, you can see her handprints reaching for points along the perimeter and pulling back to the center, or the ground. Denser application in dirty brown on the bottom left corner provides a foreground, and some more thinly applied grid demarcations in blue-gray set up the field of vision, hint at a landscape. The handprint—the most rudimentary mark of human expression and individuality—is allowed to speak here among sparebut sophisticated brushwork suggesting Fishman is still putting herself into the process wholeheartedly, in all manner available to her. Bruce Nauman’s Stamping in the Studio (1968), an artist’s meditative dance around the perimeter of possibility, comes to mind.

Fishman offers up a straightforward look at her life’s work in Coda di Rospo: returning to the rectangle, moving deftly within its confines while experimenting with different techniques and pushing the parameters of the grid just to their extreme. Aside from the emotion, mood, and storytelling in her abstraction, you sense the athleticism, the consummate movement of paint with studied and repetition.

What I’ve known for years is that the grid in my painting, which was fundamental and still is, came from two games I played. One was the basketball court, basically a grid, and I knew where my foot was at all times in relation to the foul line and the half-court line. Same thing when I would play bottle tops. You would make a court on the street with chalk, then get down on the street and shoot these bottle tops around these different boxes. And hopscotch—they all had to do with the grid. It was all about what happened when my bottle top hit the edge. You couldn’t step on that line. In 1956, I started studying Mondrian and Cézanne, and it was as familiar as any other activity in my life. That’s never changed. Always been there. The influences change. Sol LeWitt was a big influence for me, those three dimensional grids. But Mondrian, still, is one of the most fascinating painters to me. A lot of things have changed in the art world, but my work is pretty consistent. There are always changes, but there are things that always have relevance. And one of those things is the grid.

Her gestures taken in varied detail, across the works, call up the whole canon of painting history—here, a Twombly scrawl; there an impasto working that recalls Soutine; sporadic, flung drips on the surface nod to Pollock; at the bottom Richter’s blur makes an appearance—not so much an accident as a commentary. Fishman is smart and deliberate. She is (re)claiming.

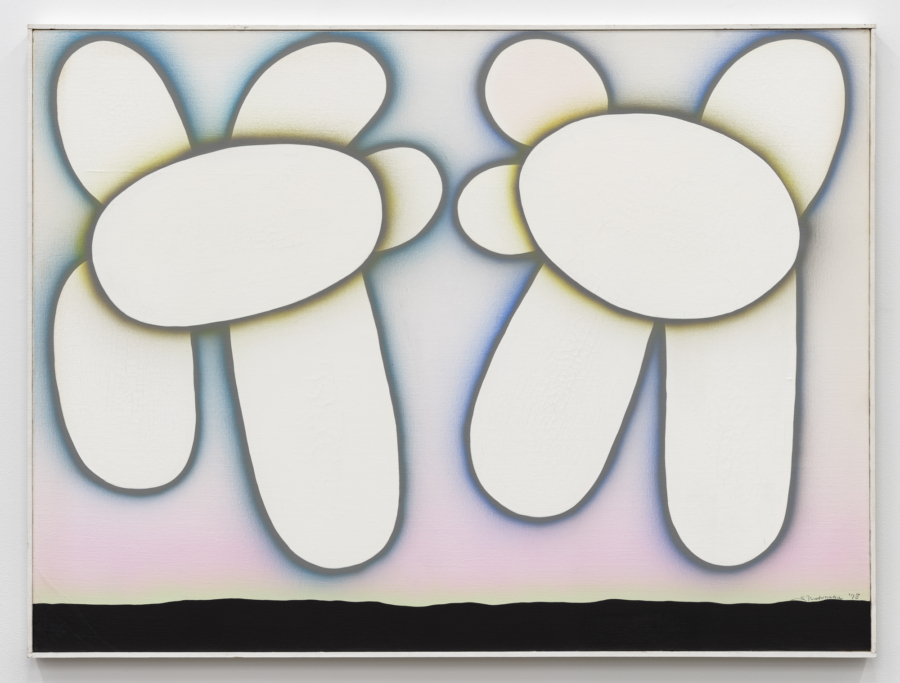

Many of her paintings feature a bisection, either with brush strokes: straight, dark gashes that bifurcate the picture plane, as in Apotheosis; or, sometimes suggested by movement and empty space, as in Bearer of the Rose. More than just reinforced grid axes, these bifurcations create a doubling and call our attention to lapses in symmetry. They’re about looking, re-looking, noticing difference and sameness the way we do when two things are placed side by side.

Oftentimes her grid play culminates in “accidental” windows. In both Traumerei and Antica Locanda Montin, the surface of abstraction is broken with what appear to be window panes. In both cases, our look “outside” is obscured, or empty. We cannot see through, and so we return to focus on the act of painting itself: the action, the worked out emotion, the energy. Her abstraction also reveals crosses, calligraphic marks and scribbles that look like rudimentary language, and other cryptic pre- symbolism.

In 1990, Fishman’s studio in upstate New York burned to the ground:

When I walked into my studio to see the extent of the fire, there was a wooden “cross” [laughs] propped up in the middle of my studio, charred. It was a section of the structure bars from the back. It was a fucking cross. I looked at it and walked out, and I threw things. People were standing outside worried about what I was going to do. And I threw things out the door, and I yelled “FUCK.” [laughter] But, I fell into a despairing mood and I got chronic fatigue; I got very sick and I was sobbing all the time. I remember Joan Mitchell called me from Paris, and she said, “Get back on the horse, Louise.”

After the fire, Fishman returns, beleaguered, to the basic nature of picture making with the most sincere intentions. Louise consulted a Jewish turned Buddhist psychiatrist who helped her refine and rethink her meditation practice, which she brought into the studio.

I was having a million thoughts, my mind was everywhere when I was painting. What I learned to do on these meditation retreats was simply go to my breath: let the thoughts be, but let them go. It was essential in my studio that I stay with my body and notice the feelings, or notice the confusion, the pride, the million things that come up when you’re working.

Rothko and Kelly, among Fishman’s influences, both have chapels associated with their work devoted to quiet contemplation. Fishman’s chapel is her studio. Her decades- long work within the confines of the picture plane reads less an ongoing struggle than a daily meditation on the possibilities of expression. Her paintings, however chaotic the gestural marks, are pictures of process: a personal, poetic, and insistent searching. She addresses what comes with each new visual and life experience, each new breath, then moves on, and then returns.

It has been more than five decades since Fishman shared her bus ride with Nina Simone. On a trip to New York from Philadelphia to meet with Louise at her studio, I am in awe at the hip coolness she maintains at 80 years old. She has always been fit and doesn’t seem her age. Her red-rimmed glasses are sassy and chic; she speaks deliberately and confidently. Chelsea is booming with construction as the mega- galleries expand their already cavernous spaces. It seems pretty sterile, corporate almost. In a way, Louise’s studio seems like a relic from another time. Then, I board a Megabus back to Philadelphia, and hop on the trolley back to West Philly; Louise must have taken it many times. It runs under the city and then comes above ground across the Schuylkill River. A young guy with a boombox blasting soul music from the back seats is singing along and calls out, “This sounds beautiful, don’t you agree?” I do. The trolley seats are bright sky blue, and the rubber, grooved floors are cadmium red with dark black, uneven streaks of street grime. There are yellow caution lines bisecting the floor, which create a happenstance three-dimensional painterly scene à la Fishman.