July 2020

Hanging in my bedroom is an exhibition poster from Ann Craven’s 2018 show at Karma. Featured, front and center, is a fuzzy bird I chose to name Toby. Most mornings, I wake up and greet Toby. I share this anecdote with Ann who sighs, appreciative of my morning ritual. She tells me she called that same bird Hit Song Bird. We each have our own name for the same little guy, and I take great comfort in knowing I got Toby’s name all wrong and that Hit Song Bird is a much better name. My relationship to Ann, having never met her in person, has been Toby (wrong name), and a phone call (far too short). For now, we are strangers at the hip. One phone call and a million past lives. Dear Ann, and so on, forever—I am grateful to know you because of the birds and the roses, and the blue, and the different versions of the same moon. Thank you.

Sunset Irises and Peonies (Gram’s Flowers, Guilford, June 8, 2020), 2020

Flowers in a vase on a stool. Feathery pink peonies and irises with lance-shaped leaves, uprooted from Boston and replanted in Connecticut. The flowers are from Somerville, to be specific, fifty years old. From Gram, to be even more specific. The flowers bring to mind—for Ann—how she and her mother used to take flowers from the graves and paint them. Her mother would say, “Let’s paint them.” Her mother, she tells me, died suddenly. For whatever reason, “Died suddenly” and “Let’s paint them” are—for me—twin sentiments.

When Ann remembers, she says stuff that sounds like a turn of phrase—the way sayings are sing-song and contain brief, negotiable wisdoms. Ann’s manner of speaking is arranged but idle. Her choice of words is a picnic. She says things like, “gardens with good edges.” She describes pure love as not being “sticky.” She says things like, “flowers in a vase on a stool.” As a child, her first oil painting was a kitten. She loves animals, beauty. She used to carry a valise with postcards—she paints from postcards. Mid-sentence, and kindly, she’ll characterize her work by saying it’s “straight from the heart.” Ann speaks in postcards. Plainness with affection, because plainness is the past, is a family of roofers from Boston. “Hard workers,” she says. The plainness is a peony, five decades old that belonged to a grandmother who died and came back to life while giving birth, back then in 1938.

Sunset Irises and Peonies (Gram’s Flowers, Guilford, June 8, 2020), 2020, 2020, watercolor on Fabriano paper, 140 lb 30 × 22 inches; 76.2 × 55.9 cm, 33 × 25 inches; 83.8 × 63.5 cm (framed)

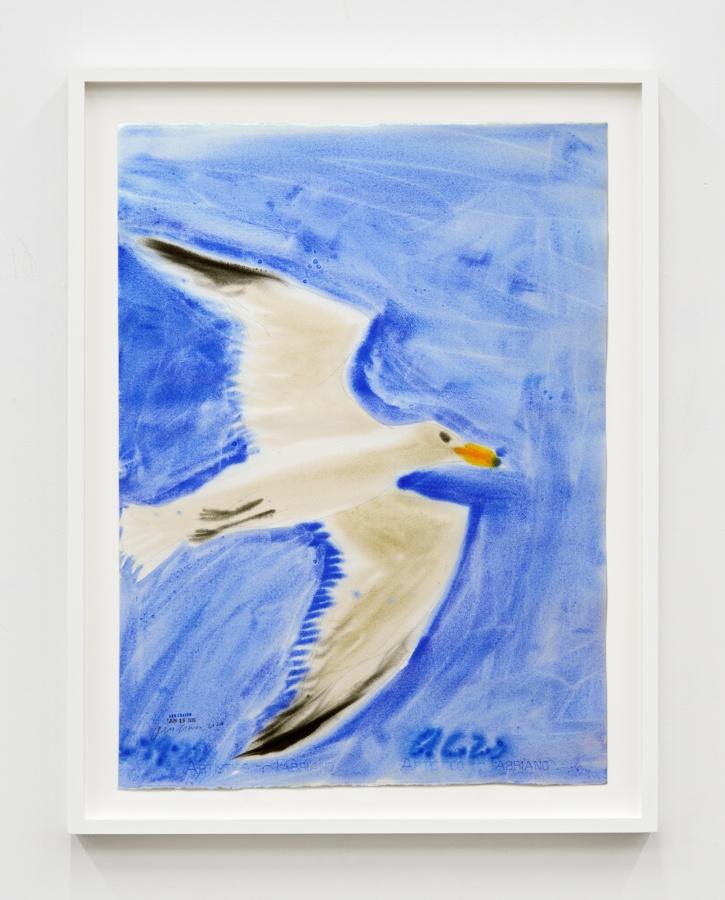

Skinny Seagull, Again (Flying, June 19, 2020), 2020

Nobody can ever convince me of a seagull’s beauty, except maybe Ann.

Skinny Seagull, Again (Flying, June 19, 2020), 2020, 2020, watercolor on Fabriano paper, 140 lb, 30 × 22 inches; 76.2 × 55.9 cm, 33 × 25 inches; 83.8 × 63.5 cm (framed)

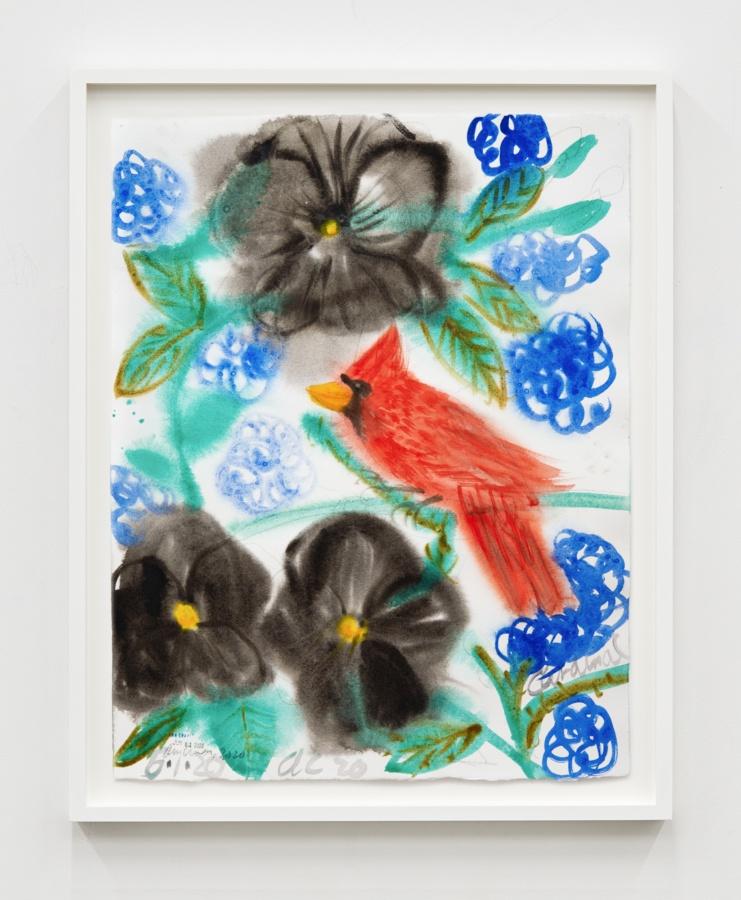

Cardinal (with Black Pansies, June 1, 2020), 2020

The photos Ann shares with me of black pansies are date stamped. February 7th and 9th, 2013. I check my email and find an exchange with my friend Lucy from February 7th, 2013. I’ve just had surgery on some teeth—the result of an accident from years prior that never properly healed. I tell Lucy I’m feeling loopy because of the pain medication but that I’m so happy to be writing her. She replies that same evening: “Tonight’s just one of those lonely Iowa nights. I’m reading about the blizzard that’s headed your way and thinking about boys who used to love me who don’t anymore and I should really get up and make some kale salad, press some garlic, grate some cheese, take some concrete steps toward something.”

Cardinal (with Black Pansies, June 1, 2020), 2020, 2020, watercolor on Arches paper, 140 lb, 26 × 20 inches; 66 × 50.8 cm, 29 × 23 inches; 73.7 × 58.4 cm (framed)

Deer (in Daisies, May 20, 2020), 2020

Stranger still is that we’ll always believe the deer appeared out of nowhere. Like some kind of glitch in the night. Like some kind of glitch on a dark road. A brown barrel on four stilts—spotted, walleyed, looking. Figurine-like. Deer are such an eBay thing. Deer, Ann tells me, are often found on condolence cards.

In the day, we’ll always say the deer came into view—we might not say anything at all. Just gasp, go Shhhh, or wave over whoever is near. My friend Echo recently texted me a photo of a deer in her backyard in Pennsylvania. It was mostly hidden inside a green meadow of tall grass. There it was, Shhhh. The deer is secret like that. The deer compels the Shhhh.

I pinched my index finger to my thumb and then pushed them apart, eager to zoom in on the deer and get a closer look, and text my friend Echo back, “How?” The deer will always be improbable.

In the Disney movie, the butterfly lands on the deer’s tail. The tail of a deer is called a scut. It’s short, erect, similar to that of a rabbit. Rabbits’ tails are also known as scuts. In the Disney movie, the deer has a rabbit friend named Thumper. In the Disney movie, their tails aren’t all that similar.

The deer is idiomatic. Visibly startled, frozen in fear. The deer is me, right now or on most days. The last few months have been strange and painful, long, somehow navy and unreal. I’ve found myself frozen in my own home—static, amazed by this spinning, looping stillness. Terror met with thrumming doubt, like the most resounding Shhhh.

(But—and I only mention them because, aren’t they so lovely?—the daisies! I’m grateful for the daisies. All I see is shuttlecocks, not daisies. Those flying objects that oblige force in order to float. They, too, create the most resounding Shhhh.)

Deer (in Daisies, May 20, 2020), 2020, 2020, watercolor on Arches paper, 140 lb, 26 × 20 inches; 66 × 50.8 cm, 29 × 23 inches; 73.7 × 58.4 cm (framed)

Blue Jay (Light through Queen Ann’s Lace, May 31, 2020), 2020

Queen Ann’s Lace is considered, per a knowledge card from the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, “an aggressive bully in North America, where it can crowd out native plant species.” Blue jays—I’ve heard—are also bullies.

Blue Jay (Light through Queen Ann’s Lace, May 31, 2020), 2020, 2020, watercolor on Arches paper, 140 lb, 26 × 20 inches; 66 × 50.8 cm, 29 × 23 inches; 73.7 × 58.4 cm (framed)

Yellow Rose (Light through Queen Ann’s Lace,Guilford, May 23, 2020), 2020

I can’t be certain but I have a feeling that, saved somewhere on a phone, maybe three phones ago, I took a picture of a rose in the rose garden at the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens, and while this might be pure fiction, I swear there was a rose variety called “Steve Martin.”

It must have been yellow because no rose named Steve would be red. I wouldn’t believe you if you told me it was pink.

Yellow Rose (Light through Queen Ann’s Lace, Guilford, May 23, 2020), 2020, 2020, watercolor on Arches paper, 140 lb, 26 × 20 inches; 66 × 50.8 cm, 29 × 23 inches; 73.7 × 58.4 cm (framed)

Pink Rose (Pink Queen Ann’s Lace Light, Guilford, May 24, 2020), 2020

There’s a recording on YouTube of Meryl Streep reading Sylvia Plath’s poem “Morning Song.” When she gets to the line, “All night your moth-breath flickers among the flat pink roses,” Meryl dances on the alliterative rhythm of flickers and flat like she’s been anticipating how one F-sound provides lift-off to the next F-sound. Meryl, I imagine, loves the soft target of a letter-F-sound because she can fold something dark and even unlucky into its fricative.

In the poem—which, basically, concerns the frequencies of new motherhood and the baby—this fourth stanza steps outside. The natural world and the night world, according to Plath, are both intimate yet big, impossibly wide with worry. The reader might picture a garden and its holy matter: breath and bloom, baby. A moth and a mother. Flat pink roses and that muted F-sound which touches on fierce attachments, distance, fate.

Pink Rose (Pink Queen Ann’s Lace Light, Guilford, May 24, 2020), 2020, 2020, watercolor on Arches paper, 140 lb, 26 × 20 inches; 66 × 50.8 cm, 29 × 23 inches; 73.7 × 58.4 cm (framed)

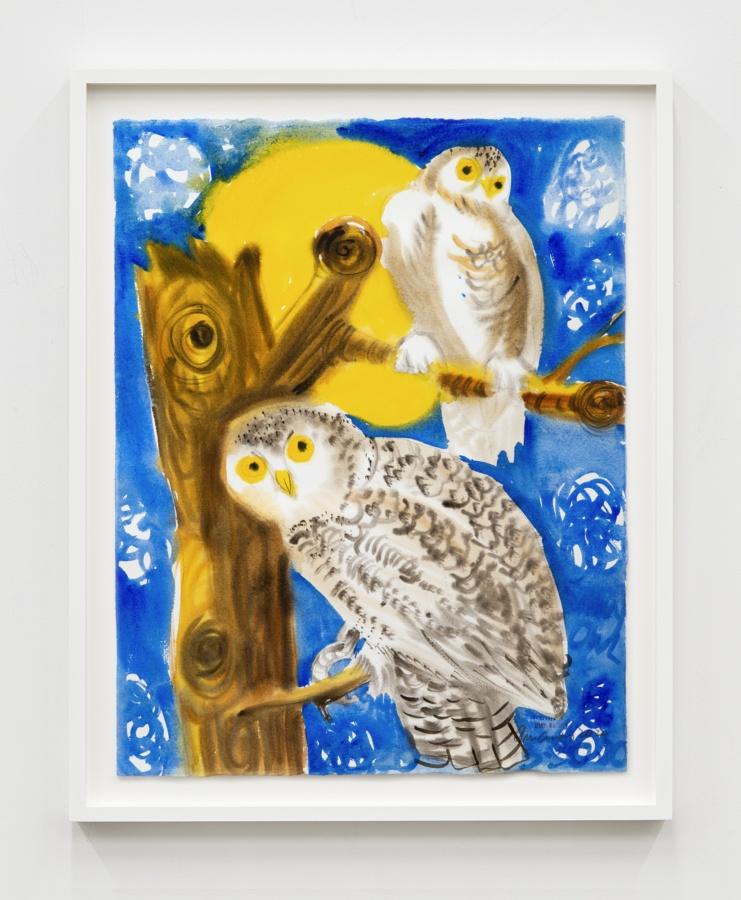

Snowy Owls (after Audubon, May 30, 2020), 2020

The tree hollows are spookier than the snowy owls. Ask Ann to talk about anything and she’ll always choose the moon.

Snowy Owls (after Audubon, May 30, 2020), 2020, 2020, watercolor on Arches paper, 140 lb, 26 × 20 inches; 66 × 50.8 cm, 29 × 23 inches; 73.7 × 58.4 cm (framed)

Roses (on Blue with Orchids, Guilford, May 16, 2020), 2020

Ann tells me about a book “that didn’t burn in the fire.” I don’t ask about the fire, when it happened or how, or how long ago, because we’ve already moved onto the next tangent, and we’re busy talking about being lazy. And soon we’ll be talking about roses, again.

Roses (on Blue with Orchids, Guilford, May 16, 2020), 2020, 2020, watercolor on Arches paper, 140 lb, 26 × 20 inches; 66 × 50.8 cm, 29 × 23 inches; 73.7 × 58.4 cm (framed)

Horses Three (on Blue, with Orchids, May 20, 2020), 2020

“My work has always been to please my mom, but she loved everything I did,” Ann tells me. “Small critiques.”

I ask Ann about inaccuracies: “Watercolor lets me go further with mistakes.”

I ask Ann about the slipperiness of imagination: “It’s what I saw, what I see, it’s vulnerable. Watercolor is a lot of letting go.”

I ask Ann about painting with watercolors as opposed to painting with oils: she calls them tough. “Tough watercolors.”

I’m not sure I would have ever considered watercolors to be tough, but then I take a look at these horses. Three of them, tough. Solid, but because they are watercolor, suddenly, too.

Horses Three (on Blue, with Orchids, May 20, 2020), 2020, 2020, watercolor on Arches paper, 140 lb, 26 × 20 inches; 66 × 50.8 cm, 29 × 23 inches; 73.7 × 58.4 cm (framed)

Cardinal (with Dogwood, May 17, 2020), 2020

Ann texts me a photograph of a postcard featuring two cardinals, one more brown than the other. It reads: “The Cardinal” the KENTUCKY STATE BIRD. The vintage look of the birds accompanied by that particular shade of red on old paper reminds me of Christmas, which I love. Ann texts me a photograph of her studio. On a white table, beside a printer, a pen, and a tall cup with orange painted stripes, sits a ceramic Christmas tree, which Ann keeps out year-round. It makes sense to me that Ann would stock Christmas year-round. Her work conjures the word “Greetings.” Greetings and Douglas Sirk (whose work is also so Christmas).

Cardinal (with Dogwood, May 17, 2020), 2020, 2020, watercolor on Arches paper, 140 lb, 26 × 20 inches; 66 × 50.8 cm, 29 × 23 inches; 73.7 × 58.4 cm (framed)

(Turn the vase into a hat and wear it)

You think the vase has become a hat; it has not.

My body has become an upside-down flower.Roses (in Isabel’s vase, with Pansies, Guilford, May 16, 2020), 2020, 2020, watercolor on Arches paper, 140 lb, 26 × 20 inches; 66 × 50.8 cm, 29 × 23 inches; 73.7 × 58.4 cm (framed)

Woodpecker (and the Moon, June 1, 2020), 2020“He’s been busy,” Ann tells me over the phone. She means you, Woodpecker. I count fourteen holes. The pure resolve of a woodpecker, the funny way this bird brings to mind Saturday morning cartoons and our earliest circuits of imagination, because woodpeckers are on the job. Dedicated, laboring. What is it about busyness and cartoons, anyways?

I remember one summer in Kolkata. The sound was ongoing—its own sound among all the other Kolkata sounds. My father raised his finger at the breakfast table and said, “Listen.” He had noticed the sound before us. It’s likely he’d been monitoring the sound the way my father—like our dog—is alert to shuffling or sounds that recur, to flat tires, to faint rustling and those damn backyard racoons who patrol our fence at night. He loves a tip-off, the rumor of a sound. You know what I mean? He loves the bird who’s simply at it. My memories of Kolkata are few but vivid, and the memory of my father scrutinizing the woodpecker—anticipating its sound—that one comes quick and rich because there we were at breakfast, listening for a pattern first thing.

Woodpecker (and the Moon, June 1, 2020), 2020, 2020, watercolor on Arches paper, 140 lb, 26 × 20 inches; 66 × 50.8 cm, 29 × 23 inches; 73.7 × 58.4 cm (framed)

Redstart (with Dogwood, June 1, 2020), 2020

Speaking of Douglas Sirk, if Douglas Sirk were a tree, he would be a Dogwood tree.

Redstart (with Dogwood, June 1, 2020), 2020, 2020, watercolor on Arches paper, 140 lb, 26 × 20 inches; 66 × 50.8 cm, 29 × 23 inches; 73.7 × 58.4 cm (framed)

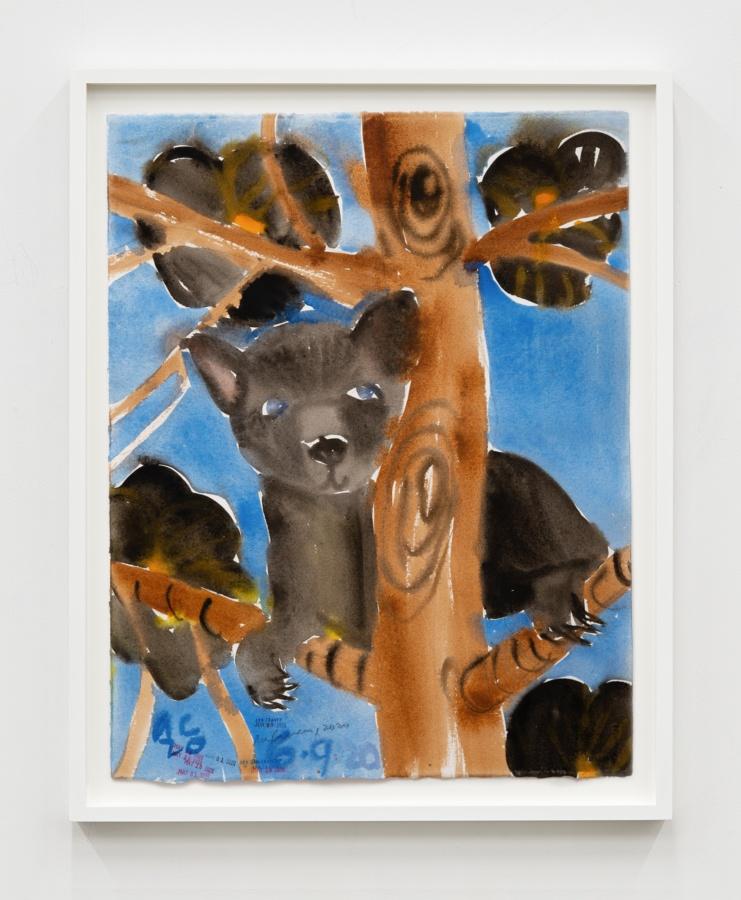

Who made the world?

Who made the swan, and the black bear?

Who made the grasshopper?

I read Mary Oliver and think of Ann, who tells me, “I literally stop short to see nature.” Ann sends me photos of her easel outside. The sky, the wind, the grass. She describes her home as it relates to “a path” or “the marsh.” The poem goes on, but we’ll re-enter it here:

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

I don’t know what a prayer is either. But I do know—sometimes I think it’s the only thing—how to pay attention. And I do know—so does Ann—how to stroll, because what else? And I do know that a black bear can climb 100 feet up a tree in 30 seconds, and have you ever heard of anything so wild and precious, and funny, because once the black bear is up there, the black bear is up there. Perched and so casual, like who are we to wonder what its plans are or how it intends to climb down.

Bear (Climbing Trees and Mountain Sides, June 9, 2020), 2020, 2020, watercolor on Arches paper, 140 lb, 26 × 20 inches; 66 × 50.8 cm, 29 × 23 inches; 73.7 × 58.4 cm (framed)