2023

Ann Craven: 12 Moons, SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia, 2023

It was after only a few moments in her presence that I sensed a warmth like sea spray in Ann Craven’s voice, and I asked her if she was from Massachusetts.

Of course she was.

I had preserved my near-perfect ignorance to meet her. I couldn’t tell from my machines what her paintings would feel like in person. I had agreed to write about her on pure instinct—I felt it was singularly ballsy to paint what is so beautiful it resists all apprehension. What is beyond beauty. The moon on water. Birds and trees. The moon itself.

Acts of love become philosophical, somehow, when one repeats them with a scholar’s attention.

“Beauty,” of course, has not overtly been a concern of art since probably the nineteenth century. Obviously we all know how much ideology is embedded in Beauty’s evolving rigors and standards. Beauty—which Rilke called “nothing”—and let us dwell a moment on that “nothing”—

nothing

But beginning of Terror we’re still just able to bear, and why we adore it so is because it serenely

disdains to destroy us.1

—capital B Beauty, which is nothing but that which serenely disdains to destroy us—so rapidly, so easily decays into . . . you know, beauty. The kind you buy creams to maintain, or make real estate decisions around.

It is not easy to paint the moon and make it new. It is not easy to give to the world a personal relationship with an entity we all think we’re relatively intimate with.

Talking with Ann was like falling into phase, if we were rhythm, or into harmony, had we been singing. It was like falling into her way of being and understanding the world. She’d served me a pot of Earl Grey tea and a merry banana. It was exactly what I needed.

It was a hot morning in New York. I’d just broken up with the man I’d been seeing since coming back to the city after my mother’s suicide. There’s nothing you can give me that I need from another human being, I had told him. That was a bit of a lie. He had a giant dick and an equally enormous brain and he was nice to me. It was just that he was confused about what he was doing with his life, and I guess I had no time, just then, for confusion.

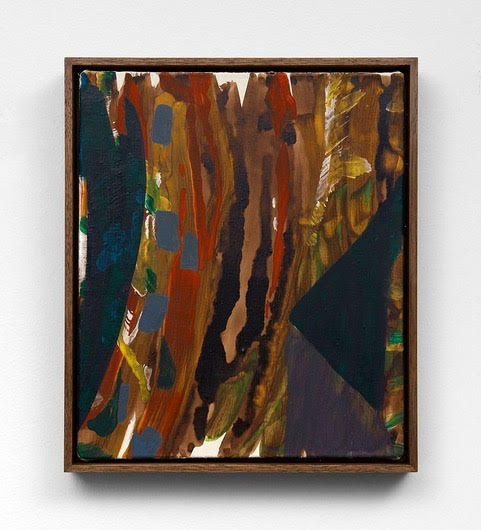

So it was with vivid joy that I was led by Ann toward the back of her studio, where the paintings were, and felt their heat and wide appetite for life penetrate my heart. It was as though the curtains within me drew open. This is a woman, I felt, who understands love and knows what she loves.

There is a melody, a kind of lovingkindness, that has never in particular been in fashion in art—and nor should it be, necessarily. Obviously such feeling easily becomes maudlin or sentimental. I myself am easily disgusted even by my own Pollyannaish sweetnesses. I felt my heart turn over when Ann introduced me to Magic and Moonlight, her dogs.

I remember, when I was little, puzzling over Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.” I thought it was weird to praise something that on the face of it is already good. Why would Joy need praise?

It was only through living out all kinds of wretchedness in the process of becoming an adult that I came to understand the depth of such a creative act. Joy’s inherent good is precisely why to undertake to praise it—and make such praise, to paraphrase Ezra Pound, feel new—would be such a very tall challenge.

When you grow up by the ocean, as I did, and when you grow up surrounded by assholes, which is what it means to grow up in Massachusetts, the most delicate and refined sentiments interact with a kind of masculine grit and eagerness for dispute and you just sort of get used to beauty moving that way. Mothers and aunts thrown in mental hospitals, sunburned uncles and cousins wrecking their bodies all day out roofing or ripping out cracked linoleum. Beer and freckles. The moon on the water. A cruel sense of humor. The moon on the water.

I have always been attracted to obviousness—subjects or phenomena that are so ubiquitous we think we know what they mean, and what we feel about them. I write my books about these things precisely because they turn out to be much stranger and more difficult to grasp than they seem.

The moon is the cosmological object that belongs to poets, more than any other. The moon is our consolation, our protector. Mary Oliver’s Twelve Moons, I hear, leant its title to this exhibition. Twelve of course marks the calendar year, the zodiac, and a modernist technique of composing music.

I feel that what Ann is painting, though, is desire itself, or something deeper and more primal, something in the body before that word gets attached to the pulling, sucking fact of the tide, which when you haven’t been in the ocean for a while, could shock you with its near obscenity.

The moon draws her out onto the roof. The moon pulls her. These paintings are charged with the energy of a relationship. It is hard to understand or feel them unless you are with them in person. They give off heat. They radiate human suffering consoled by a cosmic witness.

Serial and iterative approaches to painting—On Kawara’s Date Paintings, Etel Adnan’s Mount Tamalpais, Paul C.zanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire, Pierre Bonnard’s wife—feel like they’re about love to me. That’s not very conceptual or sophisticated of me to say. But the things I write and write and write again—I am trying to settle a relationship. I am trying to find “right relationship.” Or I am saying: I have a legitimate stake in what I see. It belongs to me, insofar as I love it. It belongs to me, insofar as it gives me its secret. It gives me its beauty. Consensually.

The moon was called “inconstant” by Shakespeare and of course we know that it waxes and wanes, pulls the tide, and governs the menstrual cycle—perhaps the most powerful dynamic in the human story, and our last enduring cultural taboo. To see seventy-eight Ann Craven moons arrayed in space produces a startling, almost architectural effect: an effect of great dignity and of stability.

An effect of fidelity.

I once had a very strange experience on a bench on the Lower East Side, facing Delancey. It was late in the afternoon and traffic was as busy as it always is. The sun emerged from behind a cloud and proceeded to warm me with a pervading rapture that was more than I had ever felt from a sunbeam. It kept on coming. I took out my notebook when I realized the sunlight was rearranging my thoughts—that it was communicating to me by changing me.

One of the things the sun “said” that day was that the moon had always known “he” was not the only sun in the universe, whereas “he” had taken some time to become reconciled to this fact. I realized, the small non-sun-intelligence me, that the moon and sun’s optical perfection, such that the moon appears just slightly smaller—even while both heavenly bodies shift in size and appearance wildly throughout the day, the month, the year—was a beautiful and also humorous trick of the cosmos. T he kind of perfection we enjoy here on Earth is a funny one. It is mathematical, but not rigidly so. It is spiritual, but not aggressively so. It is playful and affectionate while being awesome and dignified.

I perceive a knowledge or an understanding like what I experienced with the sun in what Ann Craven’s work testifies to. What I mean is I see her paintings in the tradition of portraiture. Just as I am not talking about “astronomy” or “nature” when I talk about the sun, with which—with whom—I have had this overwhelming relationship, Ann Craven is not, I don’t think, painting landscapes. She is painting someone she knows and loves, who loves her in return. She is showing what it feels like to be in that relationship. It is not lost on me that the great solar poets are relatively few, and at least one of them beat his wife. I don’t know why the sun talked to me. Maybe it was something masculine in me. Or maybe I needed a father right then. I did need a father right then. And if I could have made one up, I would have. Instead I was caught completely off guard. I had never been so surprised in my life. T he sun isn’t masculine in all cultures, but it certainly was for me that day.

I say all this to say that the dimensions of art that are perhaps least empirically “justifiable,” least-able-to-be-“defended,” critically speaking, perhaps have something to do with what Walter Benjamin and the yogis know as “aura.” This is why it is such a beguiling challenge to write about these paintings. I could write many essays vindicating the moon as a subject of study, defending what I sometimes call “menstrual consciousness,” or explaining just how the waves are a synecdoche of the moon, and vice versa. But Ann’s paintings do not need any of that from me.

I would like to propose a new theory of value. I would like to propose that the energy in the heart and the hand of the painter is aglow in what she makes. I would submit that the new criterion for how art might be judged and valued might correlate to the degree to which the viewer is reestablished in proportion to herself by what she sees. A painting cannot tell you that it knows what it means to be in a relationship. To be married. To get divorced. To take care of sick relatives. To make improvements on a house. To recover from surgery. You can feel it when you’re in the presence of something soulful and alive, a field of energy that gazes back at you, that reciprocates you.

Our lives are change, but they are also rhythm. There is something cheerful, but seriously cheerful, in the recognition that even whenever I have dragged myself outside into the moonlight in despair, or in a kind of passionate, consternated inwardness, when I have confided my complication to nothing but moonlight, it has never failed to receive what I have given it, and never failed to change me.

Key West, New Moon in Cancer, 17 July 2023

1 Rainer Maria Rilke, T he Duino Elegies, trans. J. B. Leishman and Stephen Spender (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1939), 25.