Alvaro Barrington, Dike Blair, Marley Freeman, Zenzaburo Kojima, published by Karma, New York, 2020.

Download as PDF

Alvaro Barrington, Dike Blair, Marley Freeman, Zenzaburo Kojima is available here

Sometime near the end of the 1970s on the Dick Cavett Show, Martin Scorsese would offer fellow guest and director Brian De Palma a bit of film history by revealing the inspiration for his famous Taxi Driver up-close and lingering shot of an effervescent tablet dissolving in water—making the rest of the world’s images and sounds fall entirely away for the film’s lead character and audience alike. It was the “universe in a cup of coffee” scene from Jean-Luc Godard’s Two or Three Things I Know About Her, Scorsese explains, in which the camera similarly focuses on foam swirling on the liquid surface, explicitly circumventing any firm sense of scale—or more accurately, using a cinematic leap of scale from cup to screen to underline the ties between object and perception, phenomenology and psychology, that organize (and disorganize) even the most ordinary scenes in life.

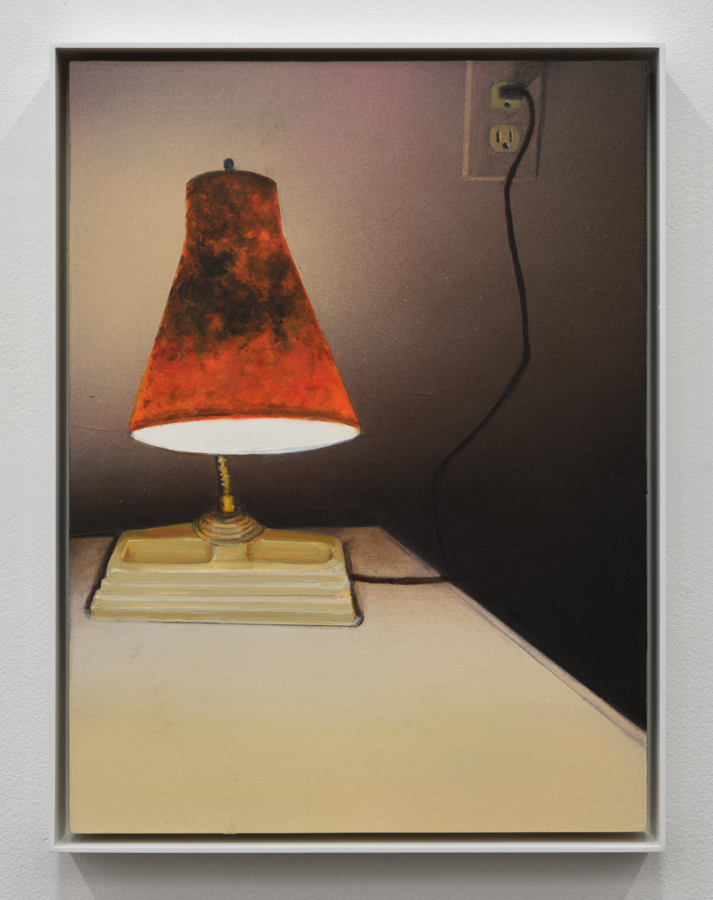

Dike Blair’s most recent body of paintings revolves around the same deceptive sense of scale, ostensibly diminutive yet opening onto another kind of meditative expansiveness. Even the artist himself observes, “I’d assumed their scale would make them feel tiny, but in some ways they’re more dynamic than [my] larger pieces.” This dynamism is also indebted to a telescopic vision that renders the most idiomatic occasions psychological in their isolating focus: a juice box at a Japanese train station; a pint glass set beside the window of an airport bar; a glass of water placed on a countertop before a diner’s table setting; a Negroni set on a Heineken coaster beside a cup of nuts and basket of chips. Significantly, all these scenes could be considered the stuff of still life. But whereas such genre studies might frequently offer allegories of the passage of time, Blair’s subjects more rightly engage the passing of time—or, again, the organization of time, and the social alignments of its cadences. Indeed, so many of his selected subjects revolve around interstitial moments and transitions: the moment after the cigarette has been crushed in the makeshift ashtray; the minutes spent waiting for the next flight or train; the drink received in anticipation of the main dish that will arrive. Blair’s images dial into, and offer entryways onto, the subconscious cues by which one orients oneself.

For decades, Blair has made paintings and sculptures taking up such subjects, often pinpointing the psycho-physiological cues embedded in commercial environments during the past thirty years (which have fundamentally altered the terms for art-making and its perennial flirtation with mass culture). In this respect, it makes sense that Blair’s subjects—like Scorcese and Godard’s examples—entail elements that possess Pavlovian sway over the mind and body, from caffeine to alcohol. It is this subtle management and unbinding of desire—as a reclamation of simple pleasure—in the face of such social forces that makes Blair a remarkable artist and one uniquely suited for our day.