Dike Blair, published by Karma, New York, 2018.

Download as PDF

Dike Blair is available here

Apart from the details, everything is always the same.

—Karl Ove Knausgaard

During the early nineties I used to drink in a bar called the Chanticleer. Located on a prominent corner on the main drag in Ithaca, New York, it had a fantastic neon sign of a Rooster with a cockscomb. Because the bar was on a corner, there were actually two neon roosters on a semi-circular marquee, facing each other as if in a mirror or a fight. I googled it recently and found it in Yelp’s list of the 10 best dive bars. My relief was palpable. Not only was it still there, but it’s status as a louche hang out could remain solidly unchanged in my mind. There was a bar down the block from the Chanticleer, whose name I have since forgotten, where most of the humanities and MFA writing grad students hung out. In the days before cell phones one could simply show up there and invariably there would be a table of folks discussing this, that, or another text as well as a thorough critique of whatever guest speaker had just rolled through town. At the Chanticleer there was very little, if any, parsing of the day’s reading. The Chanticleer was for serious drinking and playing pool and having encounters with real drunks—the ones farther along than we were: the folks who were from Ithaca, the folks who were gonna stay in Ithaca. Not everyone from the other bar came to the Chanticleer. There was a fair amount of gumption one had to muster in order to walk through its door. This all worked for me since at the time I wore motorcycle boots and chain-smoked cigarettes and was using bravado as a tool to negotiate just exactly who I wanted to be. One night, after god knows how many shots of Wild Turkey washed down with just as many Yuengling ales, I found myself wending my way to the bathroom. The wooden door had a hook and eye closure and as I slipped the smooth metal hook into the perfectly positioned eye I became entranced with the groove in the wood created by the history of this motion. The circle was worn into the door’s surface as if it had been drawn with a compass, and part of its tactile satisfaction came from the fact that this indentation, appeared to me then, in my sloshed state, a perfect marriage of line and texture. As my pants fell down around my knees, I found myself in a reverie about all of the people it took to make such a mark. Because I was in the throes of getting my Ph.D. in art history, my inebriated self marveled at the power of the indexical, the art historical term for mark making that has a one-to-one correlation from maker to mark: think a handprint in the sand, or a photographic negative on a piece of paper. Here, in the bathroom at the Chanticleer, was a complication: this indexical mark had been made by many rather than one. We had all played our part, each of us alone, to be sure, but the sum of the whole was indeed larger than its parts.

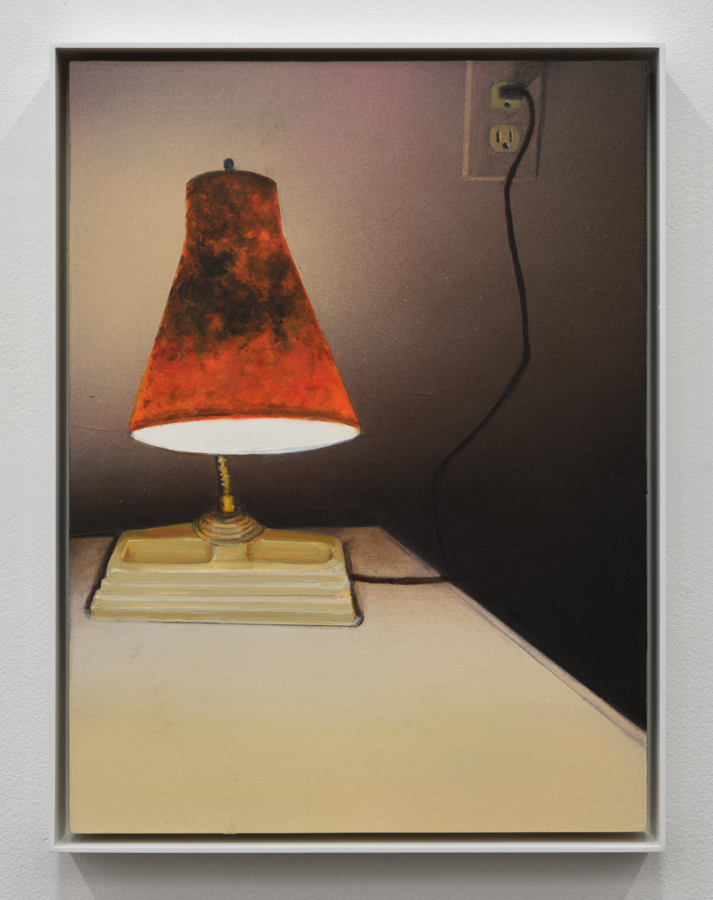

Time and again Dike Blair’s pictures provoke this kind of memory in me. Over the years his closely observed and oftentimes delicate gouaches of cocktails on bars, ashtrays on countertops, and cropped images of airplane windows that look out onto fields of sky blue paint have caused my knees to go a bit weak. The texture of the paper, the way the pigment grabs at the fibers, the way the water has caused them to both swell and dry, have all con-spired to bring on feelings of intense covetousness. I can’t tell you how often I have wondered “how difficult would it be to slip this under my coat or into my bag?”

The most recent image of Blair’s that shot through the haze and activated my memory banks, bringing me back to the Chanticleer in a way I hadn’t been since I left Ithaca in the mid nineties, is a straightforward oil painting of a door with three locks: a knob lock, a jimmy proof deadbolt, and a security door chain. Anyone who has ever lived in New York City will immediately recognize the situation. The door speaks to the time when New York was dangerous, and apartment dwellers stacked locks one on top of another, as if that would help. The door in Blair’s painting was installed before the digital world gave us “Nest” and security cameras to watch our pets when we aren’t at home. What I love about the painting, though, is not its provocation of my analogue-based childhood nostalgia but rather the way in which the painting registers, as so many of Blair’s images do, the intensity of human habit. How many times have each of us confronted the interior of a friend’s locked apartment and fumbled around with how to open the door only to step aside and mumble with a half laugh “why don’t you do this” and then watch your friend speedily move through all three locks, none of which you could figure out mere seconds beforehand? This is the space of bodily habit, the realm of the quotidian, the jurisdiction of the banal; and yet it’s the only way out of the apartment, which I mean both literally and metaphorically, for habit is the only way we can go out into the world. Without the matrix of habit how exactly would we even cohere into a self? The details of how one takes one’s coffee (in Blair it’s almost invariably in the thick old-fashioned pottery of a diner mug or the cheap take-out cup of Dunkin’ Donuts) is as stabilizing as a marriage. These small moments of personal preference and bodily knowledge behave similarly to how the fascia of the body connect muscle to bone, girding us from the ongoing effects of gravity. We step away from someone else’s door because it’s their door. We open our door effortlessly because it’s our door.

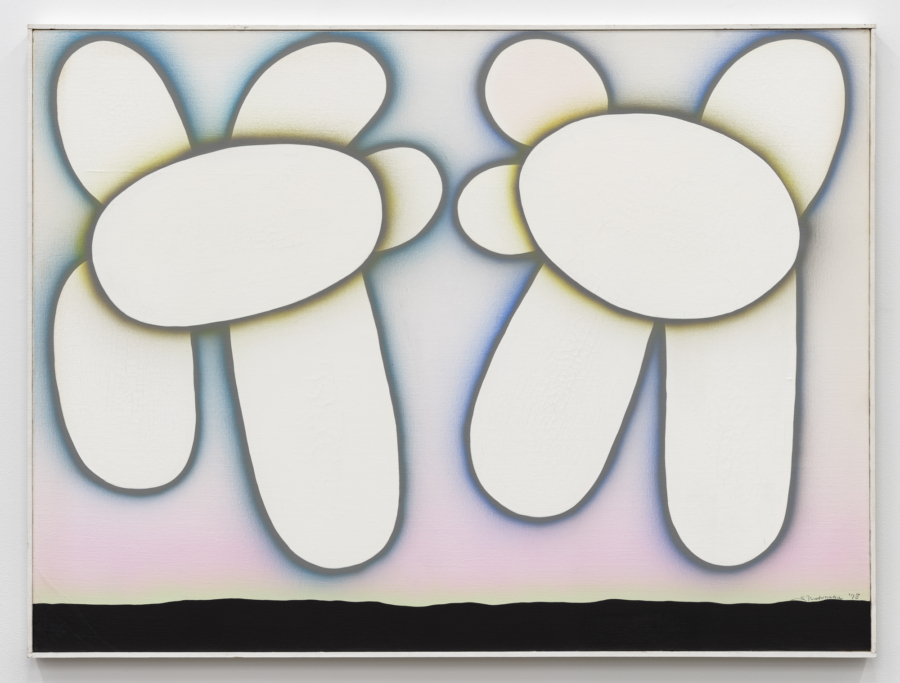

This toggling between oneself and others is, for me, the hallmark of Blair’s work. Both the psy-chic heft and the existential truth of his picture’s loneliness—their production and registration of this most human of affects—emanates from his unsentimental depiction of how habit allows us to navigate the ongoing logic of the generic and the specific. Every scene he paints—the waiting areas of airports; bars; the too harsh incandescent light on the outdoor plants at night; the blue sky out of a plane window; the seams of windows that frame the view from the bed, leaving us just a glimpse of the tree tops; the bare fluorescent bulbs on the ceiling, is generic. There is nothing here we haven’t already seen. Novelty is not what is at stake, familiarity is. And yet each image is rendered with a degree of specificity that is undeniable: that door, that hotel bar, that flight. In Blair’s hands life is as much in the details as it is in the main event. And in Blair’s world of images there is no main event other than a detail. (This is why his pictures are so modest in scale and why the “action” is pretty much always placed at the center of the composition; Blair is not one to work the edges). This is why I think his unpretentious pictures trigger such vivid memories for me. It’s a bit of a bait and switch. I am seduced by the existen-tial loneliness and the generic banality of the red bucket on the studio table, and the snowy white of the hydrangeas against the velvety black of a country sky. Just as I am equally cast back into the most particular of memories when I look at his suite of paintings of dingy ceilings and fluorescent lights. (I’m lying on the shrink’s couch, staring at the ceiling, a play of white on white that always reminded me of a cross between a Joseph Cornell construction and a Robert Ryman painting. I recall now how even then I knew I would remember that corner of the ceiling for a long time.)

This is the double gift (generic/specific) of a Dike Blair painting: first there is the exquisite image, the ethical offering of the everyday, and the space of habit as absolutely bound up with our very possibility of being, and then there are the memories such rendering o f habits induce; memories frequently folded away, not due to trauma or displeasure, but an overinflated sense of our specificity. Isn’t it a marvel to encounter an image where there is so much room to move in a space so precisely contained?

Published on the occasion of

Dike Blair

November 8–December 21, 2018

Karma

188 East 2nd Street

New York, NY 10009

Published by

Karma Books, New York

Edition of 1,000

Special edition of 100