Postcards published by Karma, New York, 2020

Download as PDF

Postcards is available here

A thirty-five-year-old Chinese Canadian painter likened to Vincent van Gogh dies by suicide in Edmonton, Alberta. That was the inconceivable headline of October 2, 2019. The heartrending death of Matthew Wong for those who knew him was parried by the skepticism about his cultural importance for those who did not.

Where is Edmonton, Alberta? For Matthew Wong it was a place of solitary productivity, a city where he knew no one, where he worked everyday from four in the morning until well into the night, for the last three years of his too-brief seven-year career as a painter. It was where he would have a nightly coffee and dessert, solo, at the Cactus Club. In Edmonton even the restaurants yearn to be somewhere far away, but Matthew Wong was there, in its nowhereness. As for many immigrant families from warmer climes, this unlikely city was where his devoted parents happened to find a second foothold in their adopted country, a chance created by necessity and happenstance. For those three years, periods of intense productivity in Edmonton were reclusive lulls in his frenetic and supercharged march through the art world, wherever his paintings were exhibited.

Where is Edmonton, Alberta? There is a reason Matthew Wong spoke of it, jokingly or not, as a “purgatory.” It was the birthplace of Marshall McLuhan and Michael J. Fox, whose military dads moved them away very early on. It was the childhood home of k.d. lang, who returned after college and played at the Sidetrack Cafe, next to the end of the defunct railroad. It is one of only four bona fide cities spread across Canada’s vast western plains: the capital of the province where Joni Mitchell was born, and where she returned briefly for art school before taking off to Toronto; where Matthew Wong was born. His Blue paintings remind me not so much of Picasso’s picaresque melancholy, but of Joni Mitchell’s Blue, the blue nowhere, the blankness “in the blue tv screen light.”1 Oh Canada. The raw predawn light of the Canadian prairies appears in his Morning Mist (2019), as a navy conifer is drenched in a rising glow, its shadow reflected on dirt-flecked snow and dwarfed by the high horizon of Edmonton’s tree-lined river valley. Matthew Wong would have gone up and down that valley, crossing the North Saskatchewan River, every early morning on his way to his studio. “Oh I am a lonely painter / I live in a box of paints. / I’m frightened by the devil / and drawn to those ones that ain’t.”2 Unlike those Albertans whose genius took them from Edmonton, Matthew Wong brought his genius to this quiet town, and left it there.

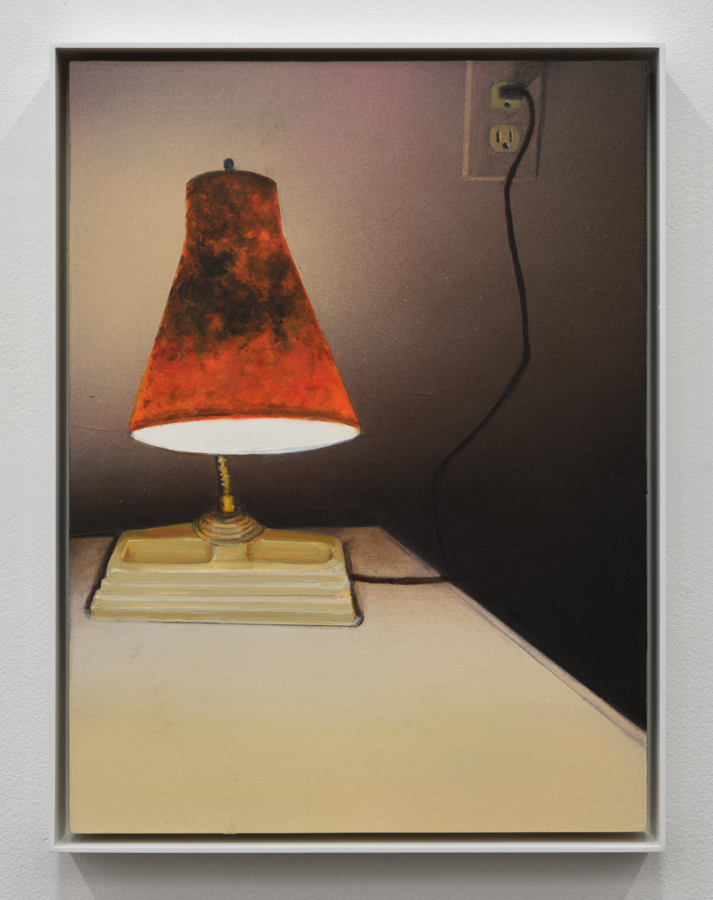

Perhaps it is an indication of the turmoil of Matthew Wong’s inner life that he found in Edmonton at least the tranquility he needed to work. Unpeopled glimpses of Edmonton appear in his paintings from 2017–19: its empty parks in the twilight (Into the Night, 2019); its birch forests (Look, the Moon, 2019); its generic skyline (Solitude, 2018); its single, straight highway to the airport (Untitled, 2019, Landscape of Memory, 2017). His studio was located in one of the least pastoral parts of town, an industrial zone near the highways of the south side. Diesel tankers and semitrucks lumber down roads of brown slush, where Matthew Wong painted on the second floor of a warehouse office park. Nearby were, not other artists’ studios, but a welding supplier, an auto lubricants manufacturer, a brewery, a soup company, and a Chinese takeout called Today’s Restaurant. Matthew Wong once wrote, “What would it look like, / If you tried to paint in solitude?”3 This muddy, nondescript world did not make it into his paintings, which either open vividly into landscapes of rock, sea, sky, forest, path, and horizon, or close somberly into wall, window, curtain, clock, and door. A poem by Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, which he chose to introduce a 2017 exhibition catalogue, resonates: “I seek a permanent home, but this structure has an appearance of indifferent / compoundedness and isolation, heading toward hopelessness.”4

Postcards.

Born in Toronto, Matthew Wong grew up in Hong Kong where he attended an international school for expatriate children. His closest childhood friend was also a child of Hong Kong immigrants returned to Hong Kong, and throughout his life, he formed deep friendships with artists who were born in a place different from where they grew up. He also read and shared the work of writers and poets like Brad Philips (b. Hungary), Mei-mei Berssenbrugge (b. Beijing), and Henri Cole (b. Japan). It feels as though they painted, wrote, and wandered together. It is not so much the dislocatedness of the immigrant which resonates across their works, but a childlike sense of the non-specificity and universality of place. They communicate as innocent outsiders and as precocious insiders of the world’s many places. Close to the end of his life, he shared Henri Cole’s poem “The Rock” with a friend. It begins: “It’s nice to have a lake to love me, / which can see under all my disguises–– / where there is only animal survival / and the brutality of the unconscious––” 5

Intimate glimpses of a sprawling world.

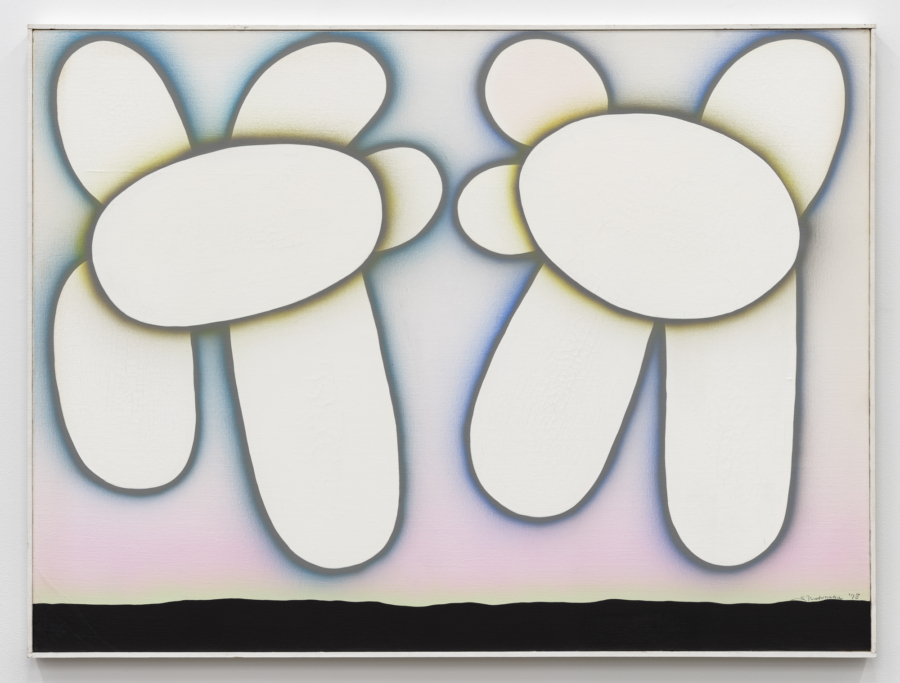

Art critics have observed that Matthew Wong’s landscapes are “uncannily familiar,”6 and they do prompt viewers to search our their memories, but he almost never titled them as places. Instead, he consistently named them as moments in time: midnight, 5:00 a.m., dawn, daybreak, 12:30 a.m., Autumn, Winter, the first snow, the gloaming, the moonrise. In the gesture of sharing a view of one moment, all of his paintings are, in a sense, postcards. For the postcard is a genre that seems to consciously elude a sense of stable locus, yet marks the times of our lives when we tried to grasp it. Matthew Wong painted at home, on the road, and in the studio. He spoke of the compulsion to finish each of his paintings in a single sitting, and talked of them always as process, rather than subject matter. Standing before paintings he finished years ago, he could recall every stroke and mark as if he had placed them just moments before. “Just paint your way through it,” he once told a younger painter friend. At a panel discussion at the Whitney, he talked about painting to Drake’s “Weston Road Flows,” describing how the song’s instrumentation evoked the energy of a young child heading to the airport early in the morning. Painting as a way to order time, to make sense of our restlessness, and as a search for permanence tells the story of Matthew Wong’s artistic maturation as well. He started in photography, began to draw in ink, painted gesturally and abstractly at first, but eventually found a way, through much foliage, into landscapes. Later, he returned to photography, by way of his friends. The hesitant, solitary figure placed in most of his landscapes is not sure where he is going, and appears paused between finding a footing and falling adrift in the undefined territory of form. But poetry—writing, reading, sharing, and performing poetry—was the constant. “You don’t have to consume the space to exist, distance, point-to-point, in / which a beloved ruin is middle ground, for example.”7

Matthew Wong’s intensity of production, his short and youthful career, and his decision to end his own life, match the story of Vincent van Gogh too perfectly. Wheatfield with Crows (1890), in which the world wants to read into the psychological state of Van Gogh’s last days before his suicide at age thirty-seven, appears as a compositional reference in many of Matthew Wong’s works. The connection to Van Gogh is one he confidently explored, even as, like most postmodern artists, he rejected biographical explanations of an artist’s work. Only two years after he began painting, he wrote a poem titled “Vincent,” timestamping it in the early hours of the morning, 7:39 a.m., on August 12, 2015. It begins: “The waves of the sky are washing / The day off my boots.” It ends, “The moon / is the color of remembering.” Matthew Wong vehemently rejected the association of this poem with Vincent van Gogh, but unabashedly, he painted his own Starry Night in 2019. The stars are different; the moon is absent; the clouds have become smoke; the river, a bay; but the fundaments are there––star, town, air, night.

On a rock.

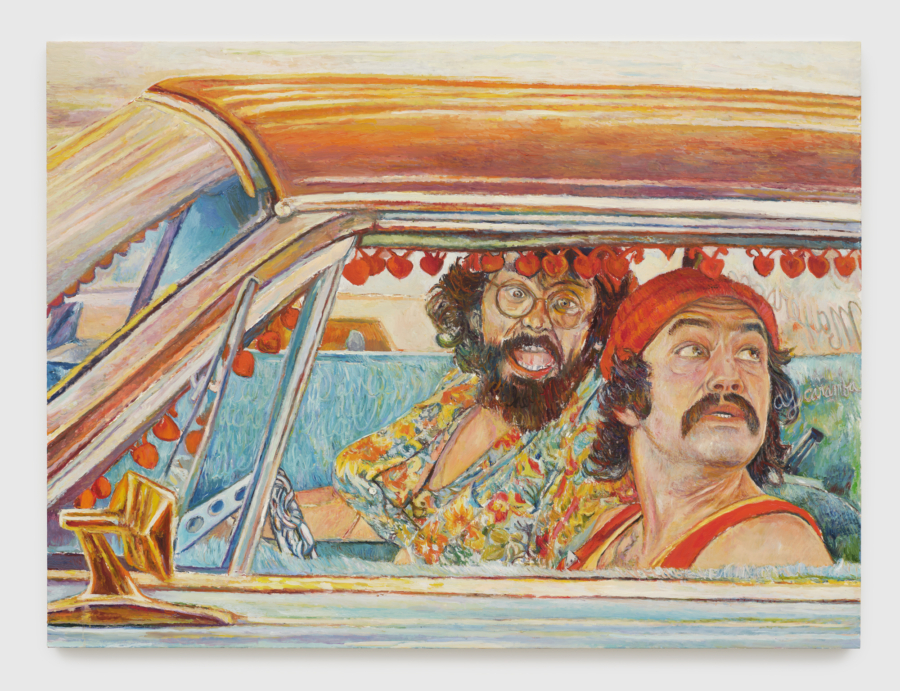

Matthew Wong learned the history and method of painting through Facebook, Tumblr, Instagram, and the reference section of the Hong Kong Public Library’s Central Branch, across from the Tin Hau subway station. Despite traveling extensively all his life, and despite the great wealth of historical influences evident in his paintings, he did not cultivate a lifelong habit of visiting public museums to pay homage to the canon of great works. His The Reader (2018) presents such a self-portrait: his bowl-cut hair, glasses unpainted, mark out a head turned down and away from a painting on a wall, immersed in a book. Matthew Wong also absorbed much of the history of modern and contemporary painting through social media, holding them in his memory with preternatural recall. It is perhaps the reason viewers see in his paintings direct citations of so many painters’ works, cut across a hundred years and more: Shitao, Van Gogh, Soutine, Rousseau, Vuillard, Cézanne, Marsden Hartley, Amy Sillman, Lois Dodd, Alex Katz, Arthur Dove. They are all there, but present too is all the hip-hop he listened to while painting, the popular movies he loved all his life, and a great deal of contemporary poetry which he read and wrote long before he began painting. He was a typically over-obsessed aficionado of algorithmized mainstream culture, tangled together with intimate internet friends and private niche subcultures: every- thing out of order and without hierarchy. “I think about all the dogmas and traditions / that are like well-made beds, with fitted sheets / and tucked-in hospital corners, to die in.”8

Between the two nowheres of social media and library books, Matthew Wong found his way into painting, and out of it when he was able. He shared his own paintings online with friends and strangers, almost as soon as he finished them. On Instagram, from Edmonton, he would sometimes post an enigmatic selfie taken from the mirror in his building lobby on his way out the door. Were these a cry for companionship or just more digital postcards? The exhilaration and anxiety of social media was such that he often deleted what he posted, or deleted his entire accounts altogether. The four corners of a book, an iPhone, a page of a poem, on canvas and on paper––painting was the place where he worked through it most successfully. “On my rock, it’s as if every- thing is lit from below / or from within. There’s no hierarchy / with pelican, water, rock, cedar, sky, and me.”9

“Never trust anyone who’s always liked themselves.”10

When meeting new people Matthew Wong often declared up front that he had Tourette’s syndrome and apologized in advance for “any involuntary eye-rolling or head jerks.” He began his struggles with mental health from as young as the age of four. At the age of thirteen, he struggled with suicidal thoughts and was diagnosed with clinical depression and Tourette’s syndrome. Not long before he committed suicide, he was diagnosed with autism. External signs of Tourette’s were not very noticeable in Matthew Wong among casual acquaintances, but those who knew him closely described elements of what the neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks once described as the “phantasmagoric form”: “extravagance, impudence, audacity, inventions, dramatisations, unexpected and sometimes surreal associations, intense and uninhibited affects, speed, ‘go,’ vivid imagery and memory, hunger for stimuli and incontinent reactivity, and constant reaching into inner and outer worlds for new material to Tourettise, to permute and transform.”11 Such characteristics, and other “savant abilities,” have in our culture been associated with genius in the arts, an association that artists like Brad Phillips (some of whose writings Matthew Wong chose to introduce his posthumous 2019 exhibition catalogue, Blue) dissect, and call us out for, in uncovering our collective complicity.

Oliver Sacks, too, guarded against the romanticization of Tourette’s and creativity, skeptical that Mozart could have been a Tourettic, and constantly questioning how to discern whether and when Tourettic artists such as Jessica Parks were truly “creative.” Sacks always referred to Tourette’s and autism as “disease,” firm in his conviction of the separation of disease and normality, even as he admitted that in the case of Tourette’s, a lifelong entwinement of the “it” and the “I” makes the two inseparable. But if Sacks described “it” as disease, so may we describe “creativity” in the same way. ‘“It’ can draw, like a dream, on the entire range of instinctual and preconscious forces, which the conscious mind can then manipulate.”12 From whence does creativity come within any of us? Who can say how they made use of “it” to bring forth the work, the images, the accomplishments that they have? What are they but glimpses at 5:00 a.m. from wherever we are, and came from?

See you on the other side, Matthew Wong titled one of his 2019 paintings. A crimson pelican glances at a lonely figure, sitting atop a solid rock. Across a bright white lake, a home, a place, is waiting. The starry night bursts over a feathery green mountain.

Postcards from nowhere.

For Matthew Wong, the sky was the limit, but the moon was the color of remembering.

1 “On the back of a cartoon coaster / in the blue tv screen light / I drew a map of Canada / Oh Canada.” Joni Mitchell, “ A Case of You,” recorded 1971, track 9 on Blue, Reprise MS 2038, 331⁄3 rpm.

2 Ibid.

3 Matthew Wong, “Thoughts on the Number One,” n.d.

4 Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, “Permanent Home,” in I Love Artists (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2006).

5 Henri Cole, “The Rock,” in Nothing to Declare: Poems (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2015).

6 Barry Schwabsky, Landscape Painting Now, (New York: D.A.P., 2019), 93.

7 Berssenbrugge, “Permanent Home.”

8 Cole, “The Rock.”

9 Ibid.

10 Brad Philips, “1996–2001, 2020, n.d.,” in Matthew Wong, (New York: Karma, 2019), 5.

11 Oliver Sacks, “Tourette’s Syndrome and Creativity: Exploiting the Ticcy Witticisms and Witty Ticcicisms,” British Medical Journal 305, no. 6868 (December 1992): 1515–16.

12 Ibid.

Published on the occasion

of the exhibition at

ARCH

5 Gkoura Street

Athens 10558

Greece

September 10–December 11, 2020

Edition of 3,000