Gertrude Abercrombie, published by Karma, New York, 2018.

Download as PDF

View Gertrude Abercrombie here

Originally written for Gertrude Abercrombie, The Illinois State Museum, 1991.

In about 1938, Gertrude Abercrombie’s friend, the late Rickey Austin, purchased a small but typical Interior from Katharine Kuh’s gallery. Abercrombie, in a characteristically enigmatic way, told Austin that he would “get a bonus with that painting,” but would have to find the bonus himself. Some years later, when he decided to reframe the painting, he discovered Abercrombie’s “bonus”: a self-portrait on paper, signed and dated 1929 (her earliest extant painting), which had been used as a backing for the later painting. What makes this hidden self-portrait so interesting is what it reveals about Abercrombie as a person and a painter. In fact, an examination of both paintings illuminates some of the essential features of Abercrombie’s art and the life with which that art was so intimately connected.

It was in the late seventies that Austin told Abercrombie of his find and her reaction was delight. “I wondered when you would find the bonus,” she said, impressing Austin with her memory. Her delight in Austin’s discovery resulted from her perception of the self-portrait as a document which she could not destroy because of its historical significance. Abercrombie’s notoriously frugal nature may have also contributed to her actions in this case; they are even less surprising when we remember that this was done during the Depression, when materials and money were scarce. Regardless, she always found it difficult to part with things, particularly if they had to do with herself.

The incident also reveals something about Abercrombie the artist. From the beginning of her career Abercrombie did self-portraits, but this one is different. It is an image of a glamorous young woman, coquettishly turned toward us; she has lovely, regular features softened by discreetly placed shadows. Seeing this image after having looked at numerous likenesses of Abercrombie in which she represents herself somewhere on the continuum from simply austere to truly forbidding is astonishing. Although Abercrombie represents herself in different guises throughout her career, she never repeats the one seen in the 1929 image. In it, she takes on the persona of her favorite actress, Greta Garbo, using as a model a well-known photograph taken by Arnold Genthe in 1925. Abercrombie’s fascination with Garbo, a woman of beauty and mystery, was common knowledge among her friends. Mystery was a quality that Abercrombie developed in her own life and art, but her own deeply held conviction that she was an “ugly duckling” checked any future exploration of the Garboesque portrait type. By the early thirties she had settled on the witch and the queen as the personae with which she felt most comfortable, and they make frequent appearances in her work from this time onward.

The room which appears in Austin’s painting is also a recurring image in Abercrombie’s work and functions as a psychic self-portrait. The interior is closed and barren, the walls around the door are cracked and peeling, the single unmolded window offers no real release; it is a reflection of Abercrombie’s own loneliness and self-doubt. The confident, flirtatious, and beautiful young woman in the “bonus” painting represents the other side of Abercrombie’s personality, one less often seen in her work. It is the many contradictions, ambiguities, and paradoxes of Abercrombie’s life—a life circumscibed by the limits of her personality—that inspire her art.

Through physical confrontation with Abercrombie’s work and the personal belongings that make repeated appearances in her work, we begin to get a picture of this enormously complicated woman. She was, on the one hand, celebrated for her warmth, humor, and generous spirit. This is the quality that is evident in the hostess of the lively and regular weekend parties attended by artists of visual, literary, and musical talents in the forties and fifties. It was at these events that Abercrombie was at her best. She was also well known for her reclusiveness, alcoholism, sarcasm, and stinginess. Her art is intimately connected with and grows out of these contradictions. Her rich and sometimes inconsistent inner consciousness is reflected in the world she created in her paintings. Abercrombie changes seemingly ordinary elements of her own world, like the pedestal and the crystal ball, into magical elements in the interiors, landscapes, and still-life paintings which are all to a great extent self-portraits.

Abercrombie was born on February 17, 1909, the only child of Tom and Lula Janes Abercrombie, who were traveling as singers with an opera company in the South at the time of her birth. Her mother went to Austin, Texas, to be with her older sister Gertrude, already the mother of six, when the time of delivery was near. The child was named after this adored aunt and her father’s mother, Emma Gertrude, as well as his sister Gertrude, who had died of diphtheria at the age of four. Shortly after her birth, the family resumed traveling, settling first near Ravinia, outside Chicago, where Lula Janes Abercrombie (who used the stage name Jane Abercrombie, taken from her family name) was a prima donna in a legitimate opera company. When she was offered the opportunity to study in Berlin in 1913, the family went to Europe. Gertrude Abercrombie later remembered being “very scared”; however, she quickly adjusted to her new surroundings. In fact, she was the only one in the family to learn to speak fluent German, acting as translator for her parents. While her mother studied opera, her father worked for the Red Cross. Their stay ended abruptly with the beginning of World War I, though they managed to get home on Christmas Eve, 1914. Almost penniless, they set out immediately for the small town of Aledo, in western Illinois, where Tom Abercrombie’s family lived.

Aledo was already a familiar place to five-year-old Gertrude Abercrombie. Before their European trip, her parents had often left her there in the care of her grandfather, Joe Abercrombie (who died when she was ten), and her Aunt Lallie, Tom’s sister. She had developed fond feelings for this extended family. After a trip to California in 1915 to see her mother’s relatives, Abercrombie began school in Aledo, another experience she described as “scary.” Jane Abercrombie began to develop goiter, which affected her voice and threatened her life. When she realized she was not going to die, she intensely embraced Christian Science, with its assumption that mental attitude cured (or caused) illness. Her career at an end, Tom took a position as a salesman and the family moved to the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago, where, aside from the eagerly anticipated summers in Aledo, Abercrombie was to spend the rest of her life.

These early experiences proved very important for Abercrombie and her art: the interest in (and natural talent for) music stimulated in childhood persisted and remained an important part of her life; her acquired fluency in German signaled a facility with language which culminated in a college degree in Romance languages and a lifelong fascination with words; the small Midwestern town of Aledo provided her with numerous subjects for paintings, and, perhaps more importantly, with a strong sense of regional identification. Abercrombie was openly proud of her Middle-American roots. Affirming her Midwestern heritage in her art, she stands to some extent with such regionalist painters as Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, Grant Wood, and Aledo-born Doris Lee.

Along with several paintings in which Abraham Lincoln makes an appearance (one of the few male figures in any of her paintings), it is in landscapes that her regional identification emerges most clearly. In a postcard to her friend, artist Karl Priebe, written from Aledo in September 1944, she notes that she is “going out tomorrow for painting inspiration.” Her urban surroundings were never a real source of subject matter, though she did produce a number of relatively traditional rural scenes, like the one seen in The Pump, done for the WPA in 1938. Even here, a tiny, solitary figure in a hat walks up the hill, giving a pleasant, peaceful scene a personal quality. Gradually the private, mysterious, and haunting elements begin to dominate the serene and conventional; landscapes like the White House and Pump of 1945 are among the last that she did without overt personal symbols. From the late thirties onward, simple block houses, horses, meaningful trees (often spiky and barren, sometimes fruitful), rocks, pumps, and wells, and the solitary female figure of Abercrombie herself with a cat, and sometimes an owl, are often present. Sometimes her Victorian furniture is moved outside and often the moon, in one of its phases, is in the dark sky. Abercrombie also painted a number of specific Aledo sites important to her, each in at least several versions—most notably, Slaughterhouse Ruins at Aledo and the Tree at Aledo. Though a small version was completed in 1955, a large-scale painting of the Abercrombie home in Aledo was never finished because, according to her daughter, she felt she could not do it justice.

Abercrombie’s own comments confirm that she viewed her work as autobiographical. In an interview with Studs Terkel shortly before the opening of a retrospective exhibition of her work at the Hyde Park Art Center in February 1977, she said: “It’s always myself that I paint, but not actually, because I don’t look that good or cute.” She added that “everything is autobiographical in a sense, but kind of dreamy.”

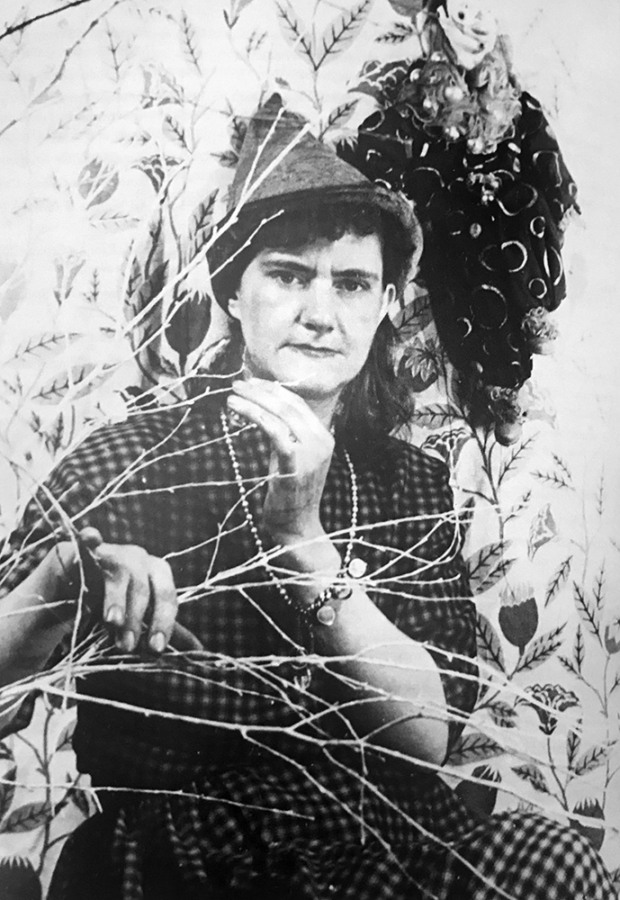

Gertrude Abercrombie, c. 1940s

Dreams had great importance to Abercrombie and were self-proclaimed sources for her paintings. She often related stories of having dreamed something and then painted it, like the Switches which she painted numerous times. In addition, Abercrombie frequently reported prophetic dreams. Rickey Austin related the following story:

Once while I was still living in Chicago, she called me to tell me she had dreamed the night before of seeing a large white whale beached, and had painted it on glass. The next morning she called in some excitement and urged me to get the morning’s paper and turn to such and such a page, which I did: there was a brief story about [a] beached whale on the New England coast.

Sometimes she imagined things only to have them appear in reality. She began to paint ostrich eggs like the one in the painting Ostrich Egg and was later given one by a friend who was presumably unaware of her paintings of this subject. A story from her own collection of anecdotes, her unpublished “Joke Book”, also illustrates this point: “Miss A. tells about a dream. Upon waking she sees the room and everything in it exactly as it was in the dreams. ‘It was like walking into reality.’” Stressing the importance of the dream or fantasy as a source for her work, she explains:

Surrealism is meant for me because I am a pretty realistic person but don’t like all I see. So I dream that it is changed. Then I change it to the way I want it. It is almost always pretty real. Only mystery and fantasy have been added. All foolishness has been taken out. It becomes my own dream.

In a letter written in November 1977 to Chicago artist Don Baum, her second husband, Frank Sandiford, says, “I think at times she was more deeply anchored to her subconscious world than she was to reality; her paintings were her visions of that world.”

Less explicitly, she refers to personal, emotional experience as a source for her work. Abercrombie transforms seemingly ordinary elements of her own world into a magical vision of enormous power, a process which she described in 1951 in the following way:

I am not interested in complicated things nor in the commonplace. I like and like to paint simple things that are a little strange. My work comes directly from my inner consciousness and it must come easily. It is a process of selection and reduction.

In addition to the autobiographical content of her art, Abercrombie liked to be the center of attention. The very first entry in her “Joke Book,” for example, is the text of a postcard from artist Dudley Huppler to Karl Priebe. According to Abercrombie, it read: “Dear Karl, Took Gertrude to the ballet last night. She didn’t like it. She wasn’t in it.” She related this story again to Terkel in 1977 and in her taped reminiscences with a friend, Dale Bernard, in 1971.

Because of her varied interests and talents, the visuals arts were not immediately a clear career choice. Abercrombie graduated from the University of Illinois in 1929 with a degree in Romance languages, and, according to her cousin Elinor Carlberg, her professors encouraged her to make writing her life’s work. She did study art after college, spending a short time at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, followed by a stint at the American Academy of Art learning commercial techniques and figure drawing. Her first job was at the Mesirow department store in 1931, where she earned fifteen dollars a week drawing gloves for advertisements. It was here that she met Tom Kempf, brother of sculptor Tud Kempf, whose encouragement started her in her career as an artist. She began painting in earnest in 1932, while working as a revamp artist at Sears, drawing beaded bags, flour sifters, and bee gloves, and by the following year was exhibiting her work at galleries and artists’ organizations.

The Depression had spawned many egalitarian art organizations all over the country. By 1930, however, Chicago already had a “no-jury” tradition. There were a number of galleries and artists’ associations in the city dedicated to the premise that all artists should be allowed to show their work, regardless of style (and sometimes regardless of quality).10 This “no-jury” mentality provided a rich medium for artists like Gertrude Abercrombie. She made frequent reference to the untutored quality of her work, allowing that she had taken “a few drawing courses [in college] because [she] liked them … and because drawing was easier than, say, history or economics.” Not only did Abercrombie consistently stress her lack of formal training in art, but regularly insisted that art is about ideas, not technique: “Something has to happen, and if nothing does, all the technique in the world won’t make it,” she stated in 1950.12 In the Terkel interview she again asserted her belief that although she was not a very good painter, she was nevertheless a good artist. In making this distinction, she articulated the principle which underlies much of the art of the twenties and thirties in Chicago. It was this attitude that drew Abercrombie to an egalitarian and progressive group of artists in Chicago, and in 1932 she exhibited with a number of them at Increase Robinson’s Studio Gallery in a show called Portraits of Chicago Artists by Chicago Artists; her contribution was a portrait of her friend and mentor Tud Kempf. But while Robinson’s gallery had a reputation for fostering innovative art, a more important force in the movement toward true equality of opportunity among artists was the appearance of open-air art fairs.

In June 1933, the second annual open-air art fair was held in the Congress Street Plaza, south of the Art Institute. Like the population as a whole, most artists were having financial difficulties in the early thirties. The fair was an opportunity for them to show their work without middlemen, fees, or juries; it was an enormously democratic undertaking and had attracted more than 250 artists in 1932, many of whom sold some of the works they exhibited. Participants included utterly unskilled amateurs, young and aspiring talents, and also established figures such as Ivan Albright.

Abercrombie not only exhibited in the second fair, but managed to sell a painting for the first time and received recognition in newspaper reviews. Equally important for her was the exposure to so many different people. She reminisced about this time with fondness and nostalgia on a number of occasions, and recalled it in her 1977 conversation with Terkel:

I met all kinds of people, classes, colors, creeds, everything … which I hadn’t known before … I was twenty-four … and it was just beautiful to meet all these people that I had never met. I had never met any colored people and very few Jewish people and there were so many odd people … I mean odd to me … and everybody loved each other.

This feeling of warmth was shared by many of the artists who participated but was particularly important to Abercrombie, who, according to her daughter, found in this “dream of community and love among friends … compensation for feelings of loneliness within her family.” It was at this time that Abercrombie’s career began to grow. She exhibited with nearly every progressive Chicago gallery that emerged in the period: in 1933, at A. Raymond Katz’s Little Gallery in the tower of the Auditorium Building and Charles Biesel’s show at Kroch’s Bookstore; in 1934, at a gallery run by Rosetta Dorsey in the basement of Abbot’s Art Store; and the following year at the Century, operated by Mary Ware and Katherine Lewis, as well as at the new gallery opened by art critic and teacher Katharine Kuh in 1935.

Because the most innovative and dynamic of these Chicago galleries typically had short life spans and few regular patrons, the artists’ organizations became crucial for the emotional sustenance of the city’s artists.16 Abercrombie exhibited with several of these groups, including the Chicago Society of Artists and the revised Chicago No-Jury Society of Artist’s Equity and the Artists Union. In addition, she began to show regularly at Chicago’s major cultural institution for the visual arts—the Art Institute—in 1935.

Abercrombie was chosen for employment by the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), the precursor of the Federal Art Project (FAP) of the Works Progress Adminstration (WPA), sometime between its inception in December 1933 and its collapse in June 1934. By the time she was selected for the WPA in 1935, she had already formed a strong association with the artistic community in Chicago; the appointment nevertheless provided psychological validation of her status as an artist. She only knew she was an artist when she was recognized as one, repeatedly associating the beginning of her life as an artist and an independent adult with the WPA appointment. The program allowed her—as it did so many others—to work full-time in an unobstructed and profitable way as a visual artist. She was paid a monthly salary of ninety-four dollars, which seemed a fortune at the time, to produce one easel painting a month. Some of these paintings were placed in public schools, but like many works produced for the WPA are no longer traceable. She continued to work for the government sponsored program through 1940.

The WPA appointment also provided the twenty-six-year-old Abercrombie with the regular income she needed to move out of her parents’ home and into her own apartment in a building occupied by many writers and artists. The strange, lonely interiors which begin to appear in Abercrombie’s work in the later 1930s are modelled on her first apartment in the Weinstein Building that once stood at 57th and Harper in Chicago’s Hyde Park.

Gertrude Abercrombie in front of Slaughterhouse Ruins at Aledo, c. 1937

In addition, the most important friendships of her life were formed at this time. She met Wendell Wilcox in 1934, and in 1935 met James Purdy and Karl Priebe, with whom she developed extremely important, enduring relationships. She also had her first important love affairs, relationships with Bob Davis and artists Franklin Van Court and John Pratt.

Llewelyn Jones, literary critic of the Chicago Post, was impressed with her work when he saw it at the Grant Park Art Fair in 1933. He introduced her to Thornton Wilder, who was then teaching at the University of Chicago. Abercrombie had been impressed with Wilder when she heard him lecture on Greek drama several years earlier.20 She described the experience in her 1971 discussion with Dale Bernard: “I didn’t know what he was talking about because I was too fascinated with his personality.” When Gertrude Stein came to lecture at the University in April 1935, at Wilder’s invitation, he asked Abercrombie to attend. She told of this meeting many times:

I said may I bring my friend Wendell who likes her writing? And he said yes. And so began a romance of Wendell and Miss Stein. A lot of people … horned in on it and I didn’t get any part of it except a lecture on art which subsequently got me a 100-dollar prize at the Institute. Miss Gertrude Stein said about my paintings “they are very pretty but girl you gotta draw better.” I knew I could. I went right home and painted a painting that won a big prize at the Art Institute.

Indeed, Abercrombie’s There on the Table of 1935 won the Joseph N. Eisendrath Prize at the Art Institute’s Chicago and Vicinity show the following year. Abercrombie was raised on classical music and was herself gifted musically. She claimed to have perfect pitch and could whistle and hum simultaneously in harmony22; she played piano and could improvise well enough to play along with the professional jazz musicians she knew. Jazz was one of the great passions of Abercrombie’s life, particularly the bebop which began in the forties. Just as she preferred the naive and direct to the traditional and pretentious in the visual arts, she favored the innovative, improvisational qualities of jazz over the more conventionally pleasing forms of contemporary or even classical music. Again, the aspects of art that were important to her were ideas and feeling; technique was secondary, merely the means to an end.

Many of Abercrombie’s non-musician friends, including Thornton Wilder, shared her interest in music. Karl Priebe, who had a passionate enthusiasm for jazz, began introducing her to black musicians in the thirties. The house she lived in at 5728 South Dorchester from 1944 until her death became a gathering place for jazz musicians who were on the road. Among the performers and composers she befriended were the members of the Modern Jazz Quartet, Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Rollins, Charlie Parker, Max Roach, Jackie Cain and Roy Kral (who performed a piece called “Afrocrombie”), Sarah Vaughan, Richie Powell (composer of “Gertrude’s Bounce”), and Cyril Touff. Classical composer Ernst Krenek rented the entire second floor of her home while writing an opera. Composer Ned Rorem knew Gertrude from his Chicago childhood and often visited her when he came to town. One of the last paintings she did was an illustration for the cover of a record album by the composer and jazz harpist Orlando Murden. Many of these relationships endured for decades.

During those years Abercrombie hosted regular parties on Saturday evenings and jam sessions on Sunday afternoons featuring contemporary music performed by her distinguished visitors. She occasionally played the piano and did scat singing; at the end of her life, when she was bedridden, she accompanied the musicians with a drum kept by the side of her bed. One friend remembers a party where the musical fare was coupled with spontaneous performance by dancers Katherine Dunham and Sybil Shearer. All of this was accompanied by liberal amounts of alcohol.

Abercrombie’s environment at this time was indeed a heady one, combining music, literature, and visual arts. One of her closest friends of the 1930s, James Purdy, gives us some insights into her bohemian salon in his novel Malcolm, in which the artist Eloisa Brace is a thinly disguised Gertrude Abercrombie. With her magnetic personality and open-door policy, the artist attracted a wide variety of interesting people to her home; she was the center of these gatherings, the self-proclaimed “Queen of Chicago.” When she was presiding over this Midwestern American salon, a happy and assured Abercrombie emerged. Her daughter described her at these events:

She was gay and radiant at these. Yes, she was the center. She was happy and expansive and felt free and expressive and had wonderful exchanges with all these people. She was blooming, she was flying … and the sound of her laughter would float over the music and carry the party into her sky … she would be sailing in her element and this was her glory and this was in her paintings too.

She often told her daughter that “she knew everyone who was important,” indicating her belief that if she didn’t know them, they couldn’t have been worth knowing. She was the final authority, giving herself the power to condemn to insignificance anyone who was not in her circle.

In fact, by 1940 many of the themes of her life were well established. She had formed strong relationships in the artistic, literary, and musical communities which continued to grow and develop over the years. In 1940, she married attorney Robert Livingston and her only child, Dinah, was born in 1942. Professionally, she had established herself as an artist, tried out most of the materials she would use, and become as accomplished technically as she would ever be. She had exhibited extensively, formed associations with progressive groups and established herself with more conservative institutions. By age thirty, Abercrombie had touched on nearly all the subjects which would occupy her as an artist for the rest of her life.

Early in her career, a group of personal objects begin to make regular appearances in her paintings. Because of their repetition in her work, some of them begin to function as personal emblems. Among these are the Victorian furniture and black pedestal, the stoneware compote and pitcher, carnations, gloves, owls, and bunches of grapes. Although Abercrombie painted portraits, still lifes, and landscapes, one of the most persistent, interesting, and revealing images in her oeuvre is her own room, repeated over and over again with almost infinite variation, but curiously little development during the course of her career. The room functioned for Abercrombie as a psychic self-portrait, the translation of a private vision rooted in dream and fantasy into the precise, concrete terms of this world. By looking carefully at this theme, it will become apparent that her other subjects often functioned in a similar way.

Typical, although painted well into her career, is the interior Gertrude and Christine of 1951. It is her own room, which represented physical freedom from the rules and regulations of the home of her parents, as well as financial independence and adult responsibility. In the painting, the artist appears in the center of a spare room with gray walls and a black floor. She looks piercingly out at us, holding her body in a rigid position with arms pressed to her sides. The only objects in the painfully bare room are a cat connected to the figure by an elegant, narrow blue ribbon, and a broom leaning against the wall in the corner. There is a door on the back wall. The room is more than austere; it is barren. The simplicity of composition and the few objects represented are enhanced by the minimal use of color, the dominant grays and blacks enlivened only by the artist’s pinkish dress and the blue ribbon linking her to the cat. We can observe that color is used consistently as an index of emotion in Abercrombie’s work. The peculiar airless quality that is apparent in the painting, the feeling of looking into an aquarium, increases the sense of mystery conveyed by this unusual collection of objects.

She depicted herself, on one level, as she was: this was her Victorian room in which a domestic object, the broom, was placed in the corner, and Christine, the cat, sits patiently. It is interesting to note in this context that Abercrombie’s painted rooms are always a model of good housekeeping. There is never a sign of disorder or dust; often there is nothing to get dusty. In contrast to her actual living conditions, her painted environments are pristine. According to Abercrombie’s old friend, the writer Wendell Wilcox, housekeeping chores irritated her enormously. She vowed never to do a bit of housework when she lived in her own home, and by all accounts kept this promise. Wilcox said he always imagined her disappearing into the pile of clothes, rags, and liquor bottles that cluttered her first apartment in the Weinstein Building. Her cousin Elinor Carlberg observed that early in her marriage to Livingston, he did all the cleaning; it was simply not in her purview. Later she had a loyal cleaning woman who worked for her for over twenty years. The house was cluttered but reasonably clean.

Her mother was extremely fastidious and demanded the same of her daughter when she lived at home. Her parents, and her mother in particular, were conservative, frugal, and very proper. According to many friends and relatives, Abercrombie’s parents, as strict Christian Scientists, considered smoking, drinking, and the generally wild lifestyle of their daughter inappropriate. Abercrombie’s relationship with her mother was polite but strained. She resented her uncompromising attitudes, particularly in regard to religion. Her bitterness is hidden beneath the humor in an entry in her “Joke Book”: “Gertrude at twenty and ill with high fever and hysterical with it said finally to her mother whose Christian Science made her want to deny reality, ‘Mother, I just love sticks and stones.’” Indeed, they had very little communication after Abercrombie moved into her own apartment.

In addition to the repudiation of Christian Science and religion in general, Abercrombie rejected her mother’s musical tastes, actually refusing to listen to the operatic music so important in her mother’s life. At the same time, however, she too was involved in art and music, living a life of artifice and theatrics under their spell. The broom may have special meaning to her, as a representation of her mother and the attempt to order the world through her art. It may also represent the internalization of the very things Abercrombie so vehemently rejected. Seen in this way, the austere room serves as an indication of the deep maternal deprivation from which Abercrombie almost certainly suffered.

Abercrombie was also frugal to a fault, a quality she found unpleasant in her parents but attributed to her Scotch heritage. She always felt materially poor. She refused, for example, a loan to a devoted but penniless friend suffering from terminal cancer because she really believed she could not part with the money. In her typically earthy and humorous manner, she accounts for her frugality:

I figured out why I am stingy about paper. My parents, when I was 6 ½, only let me use 3 sheets of toilet paper for no. 2 and an old rag for no. 1. They were that poor. A Freudian explanation.

Later in life she began to hoard things, both as a way of enriching herself internally and externally and, paradoxically, as a way of hiding things. According to Dinah, her mother’s gaze penetrated every corner of the house and only she knew where to find things in the clutter.

Not only was she frugal with material things in her life, but the objects in her paintings are doled out in a penurious manner. Her old friend, the late Emma Loeb, even described her technique as frugal, saying “she was afraid to put one extra stroke on her paintings.”

In Gertrude and Christine, Abercrombie appears as a witch, her black cat and broomstick suggesting her magical powers. In many of her paintings she is accompanied by owls, cats, broomsticks, magic wands, crystal balls, and other accoutrements of the witch. This recurring imagery of sorcery and witchcraft is conscious and meaningful. In her interview with Terkel in 1977, Abercrombie said, “I am a witch, oh, that’s true. I have been called a witch many times.” The witch role was an assumed role like others in her life. For example, knowing the impact her appearance would make, Abercrombie, according to her daughter’s recollections, “would come to school in her gray, pointed velvet hat and all the kids would laugh and say ‘Your mother is a witch.’” She enjoyed the power this artifice gave her over others who would fear or recoil from her. It was also a way of attracting attention.

A number of recurring themes in her work explicitly explore magic or sorcery. Among them are Fortune Teller, in which Abercrombie sits at a table in the barren interior of her typical room. The crystal ball, a palmist’s schematic rendering of a hand on the wall, and the cards she is placing on the table allude to magic. The horse looking in through the window is, as always, modelled on a small sculpture owned by Abercrombie. It is mesmerized and controlled by the sorceress.

Magic is the subject of the “levitation” or “floating lady” theme, in which Abercrombie is supernaturally suspended in the air. Sometimes a static and uncommunicative male magician resembling Abraham Lincoln presides; sometimes she levitates alone in a room. Abercrombie’s Victorian chaise or the rectangular marble-topped table are the supports from which the floating figure rises.

Abercrombie uses this marble-topped table as the focus in a series of related paintings often called “Marble Top Mystery.” In the least mysterious of these, like The Magician, she simply presides over a group of familiar and personal objects, including a shell, pitcher, crystal ball, flat-brimmed hat, a cat, and owl. In the more mysterious versions, we see a figure, and sometimes other objects, emerging from a hole in the table. The elongated table in the possibly unfinished Marble Top Mystery has two holes. Abercrombie’s almost disembodied figure is paralleled by its psychic double, a dead tree growing out of another opening in the table’s surface. In the background a mountain topped by a lighthouse, a recurring image, looms beneath a single cloud. The peculiar combination of elements in the painting reflects the desolate, empty, and trapped state in which Abercrombie depicts herself.

The frequent presence of cats in Abercrombie’s work represents another aspect of the imagery of sorcery. She loved cats, the witch’s familiar, and always had several in her household. Despite her frugality, she lavished great care on them, feeding them fresh kidneys even when she was an invalid in what she perceived as impoverished conditions. In Gertrude and Christine she is connected umbilically to the cat. In the Cat and I woodcut, the artist is accompanied by a large black cat whose face is a negative image of her own. In a more humorous image, Thirsty Cat, the cat alter-ego attempts to get a wine bottle off the table. During her pregnancy, Abercrombie told Elinor Carlberg that she could imagine giving birth to kittens but not to a person.

In Gertrude and Christine, she is the authority, the center, dominating both the space and the cat. On another level the room becomes a metaphor, then, for Abercrombie’s self, her psyche—and the image takes on even deeper meaning. It is an image of her actual surroundings as well as a magical reworking of her environment to exert control over it. While neat and orderly, however, the room in Gertrude and Christine is almost empty, and even more importantly, impenetrable. The door in the back wall between Abercrombie and her cat does not open. There are no hinges, hence no possibility of opening to forge a connection to the world outside. In the act of gaining control over her world Abercrombie has had to create boundaries between the room and the outside world. If the room is a psychic self-portrait, it is an image of Abercrombie’s internal emptiness and her inability to connect to others.

Although these austere and haunting rooms are occasionally richer and more replete with still-life elements, they remain secure enclosures with no communication to the world outside. The repetition of this theme throughout her life parallels her unending struggle with the fear that assailed her—fear of being alone in the world, her inadequacy discovered and recognized. Her daughter describes Abercrombie, seemingly open and uninhibited, as guilt-ridden, particularly in relation to sex and drinking. Abercrombie felt unloved, first and foremost by her excessively reserved and undemonstrative mother.

Surrounding herself with good friends was Abercrombie’s way of getting attention and love; many of her friends were people she could dominate, particularly men who affirmed her own view of herself as a regal presence, a queen. Karl Priebe, Dudley Huppler, and others often addressed her as the “Queen” or “Queen Gertrude” in their letters to her. In describing Frank Sandiford’s relationship to her mother, Dinah Livingston said, “[he felt] grand and wonderful because he was chauffeur to the queen.” This is made explicit in some of her paintings. For example, in A Game of Kings, a crowned Abercrombie oversees two lions playing chess on a Victorian table in the foreground, while in the distance a tower-rook on a hill is visible. The visual and verbal punning, so beautifully realized in this image, are characteristic of Abercrombie’s work. Her love of games, her furniture, even her moon are in the painting. Any doubt we might have about it being her property is dispelled in a half-humorous comment made in a 1971 letter to Karl Priebe on the occasion of a moon landing: “Oh those doll-baby nuts going to the moon finally made a ‘hard dock.’ And as you well know it’s my moon up there. Intruders?”

In the 1955 Queen of Hearts with Ball and Jack, Abercrombie substituted the Queen for the King that owner Margot Andreas had requested.32 Even a seemingly simple still life relates to personal aspects of Abercrombie’s life: Dinah recalls her playing solitaire each afternoon, thinking up new ideas for her painting while she played; the jacks and ball appear as early as 1935 in There on the Table, and reappear again and again in her work.

Wendell Wilcox describes both Abercrombie and her mother as “absolute[s]…. You just live according to their standards and one slip and you will just be beaten unmercifully.” Less sympathetically, another old friend wrote in 1980: “She was actually incapable of affection and she loved to manipulate very much as a child does—the only difference is she knew what she was doing—past a child’s knowing.” Later in life her loneliness and disappointment with her friends was expressed numerous times. For example, she wrote to Karl Priebe in 1976 when both were ill: “I wish I had a brother such as yours. I have batches of friends but no-one to watch over me … in my solitude.” Her art was an arena where these fears were confronted and momentarily mastered.

The reality of Abercrombie’s life, filled with friends, parties, and professional success, may initially seem contrary to the foregoing interpretation of her work. During the forties she exhibited regularly at the Art Institute, the Renaissance Society, and with the Chicago Society of Artists. She participated her first show in New York in 1942 at the Passedoit Gallery. She painted prodigiously, producing more than sixty paintings in 1945. She continued to enjoy success as an artist and as a personality even after her first marriage deteriorated and she was establishing her second, to writer Frank Sandiford, in the late forties.

Gradually, the feeling in the house on Dorchester changed as well, providing us with another index of Abercrombie’s emotional life. When Abercrombie and Livingston moved in, she decorated the three-story rowhouse with Victorian furniture upholstered in purple and beige striped fabric against dark grey walls. However, the bright and cheerful interior became darker and darker as the decade progressed.36 This darkness sometimes manifested itself in Abercrombie’s painting; some of the works dating from as early as 1942 are very difficult to distinguish because they are conceived almost entirely in shades of gray, black, and dark green.

The unchanging nature of the representation of interior space is characteristic of Abercrombie’s work in general. Aside from a few unsatisfying attempts at abstraction early in her career and in the early fifties, she focused on several subjects which continued to appear during the course of her career with enormous variation but little aesthetic development. Like the interiors, the still lifes and landscapes become formulaic; only the details change.

Although she worked in a loose and painterly style early in her career she soon settled on the precise style that characterizes most of the work from the early forties to the end of her life. Occasionally, Abercrombie’s style became hesitant as a result of the demanding emotional content of the work. For example, the few paintings in which Dinah appears have a tentative quality. In Dinah Enters the Landscape and Gertrude Carrying Dinah there is an awkwardness bespeaking Abercrombie’s discomfort in her maternal role. Her difficulty with her own mother made it nearly impossible for her to give to her child; at the same time, she identified with Dinah’s isolation and loneliness.

The only exception to this rule were the portraits, which she produced in great numbers at the beginning of her career, probably because she had willing models. Her first subjects were family members, like her cousin Elinor Porter Carlberg, and friends, like the sculptor Tud Kempf or her “cousin,” Martha Parsons, an accomplished pianist and member of the Hyde Park artists’ community. Comparison of Emil Armin’s portrait of Parsons done in 1924 (Tones) with Abercrombie’s clearly evidences her emphasis on that which is “a little strange.” Armin’s Parsons appears perfectly normal, jaunty even, against a colorful, decorative, and energized background rhythmically resonating with the musicality of the sitter. In Abercrombie’s image, the ponderous figure with slightly off-center features looks out of an almost monochromatic brown-yellow canvas. After seeing Abercrombie’s representation, it is no surprise to us that Parsons spent years in a mental institution.

Although she was a talented and perceptive portraitist, she abandoned this genre early, aside from an occasional commission, such as the portrait of Richard Purdy done in 1955. She continued, however, to produce many self-portraits through her entire career; among her final works was a pen-and-ink self-portrait in the collection of Hugh Cameron, dated to 1968. As her art became a means of dealing with her inner world, of introducing an order that was tenuous in her life, her interest in depicting others dramatically waned. When she said of the female figures in her work, “it is always myself that I paint,” she could have been referring to any of her subjects. Wendell Wilcox said it even more bluntly: “The whole opus is Gertrude because that’s all there was in [her] world.”

The objects which appear in the 1941 Self Portrait of My Sister are personal emblems which reappear elsewhere. Her black gloves, an allusion to her first drawing job, take on a life of their own with their jittery activity in the lower part of the painting, while her hat is adorned with a familiar bunch of grapes. As we have already seen, even a still life with no ostensible emotional content, such as the tiny 1945 Bowl of Grapes, becomes a self-portrait by the inclusion of the bunch of grapes and the gloves.

The white stoneware compote is another personal possession which makes frequent appearances in her work. We see it in the tiny Glove and Compote (1953), in which the elements of the 1945 Bowl of Grapes are set against a dark sky with an Abercrombian sliver of moon. In a witty and surreal touch, the empty glove holds a grape between thumb and forefinger.

In Pink Carnations, a larger work done for the WPA in 1939, the white compote is filled with carnations, the “national flower of Gertrude’s creation,” and rests on a cloth atop the familiar marble-top table. Her presence is more than implied in this still life. She appears, a solitary woman in a vast and barren landscape, in a picture hanging on the wall behind the table, a device Abercrombie often employed to extend or enhance the meaning of her images. In typical naive fashion she later credited the image on the old Quaker Oats box with inspiring this idea.

Her room as well is a self-portrait, whether or not she is physically present. In a painting of 1952 entitled Intermission (Telephone), we see an image of a room furnished in typically sparse fashion with an overturned chair and table on which there is a pitcher, cup, and spoon. In this room Abercrombie has made a fairly explicit statement of her presence by the use of the picture within a picture. The room is an interesting one in Abercrombie’s oeuvre because there is a sense of involvement, of activity, so conspicuously absent in the other interiors she painted. An attempt at communication, indicated by the unhooked telephone and what may be a note on the floor, has failed. Her presence as a disembodied head in the portrait on the wall reinforces the fragmentation conveyed by the image. This fragmentation is seen in her work in several variations, ranging from images of segmented body parts floating in the familiar room seen in Split Personality, to an early image like Head on a Plate, in which Abercrombie’s own head is presented to us like that of John the Baptist. As in a number of early works (for example, Blue Still Life of 1934), the objects are arranged on a heavy wood table covered with a cloth. Head on a Plate functions as a psychic pendant to There on the Table, with its fragmentary headless body; they both include the ever-present cat and a toy jack.

The Interior of c. 1938 is an archetypical room of the most austere kind; it is a larger variant of the Interior of the same year purchased by Rickey Austin. In it are elements that became familiar components of the artist’s real and imaginary world: the unadorned walls, the high, square, unmolded window, the familiar, tightly closed, hingeless door, a broom and round table. The most notable feature of this particular interior is the cracked and peeling plaster around the door. This kind of image—with its familiar severity and bleakness, its broom reminiscent of the compulsion to clean and order as well as magically transform, its door non-functional—is typical of Abercrombie. With the cracked walls indicating the deterioration of structure and the impossibility of escape, it is among the grimmer and more hopeless of her scenes.

Different furnishings are present in Picture in a Picture in a Picture of 1955, in which a Victorian chaise placed in the corner and the picture on the wall repeats the image of the interior of the room, dooming the inhabitant to eternal confinement. The window is missing but a note has been slipped under the door. The note seems to allow for the possibility of communication with the outside, yet the tightly closed door and the picture on the wall render that communication incomplete at best. A slightly smaller variation of this image is seen in Double Image of c. 1951.

Frank Sandiford, Dizzy Gillespie, and Gertrude Abercrombie at an outdoor art exhibition, 1956

Sometimes the occupant of the room is identified as Countess Nerona, a reference to the heroine of a popular novel by Wilkie Collins, The Haunted Hotel. Represented in exactly the same way as other female figures in her work, she serves as yet another alter-ego for Abercrombie, characteristically drawn from popalar fiction rather than a more elevated literary source.

Compared with the barren interiors already discussed, The Past and the Present of c. 1945 is warm and inviting. Fairly large for a work by Abercrombie, it is also filled with a greater number of objects in a richer variety of colors. The earliest references to this work, in Abercrombie’s records and exhibition lists, identify it as Weinstein Interior, a reference to the building in which Abercrombie had her first apartment. Together with the revised title, The Past and the Present, the original title offers clues to the meaning of the painting. This is the first of Abercrombie’s own rooms, and is represented with much less austerity than her other interiors or the landscape in the picture on the wall. The house depicted in the painted landscape on the wall is the rowhouse at 5728 South Dorchester where Abercrombie moved just before she made this painting. It is isolated in a barren expanse with a spiky tree and a single storm cloud. By making the past subject of the painting and the present the painted inset, she conveys the importance of the imagination as well as the mind in determining reality. In this case, the relative warmth and comfort represent the memory, perhaps embellished, of an earlier time in contrast with the present, represented in the picture on the wall.

One is reminded this context of Gaston Bachelard’s stated aim in his The Poetics of Space:

I must show that the house is one of the greatest powers of integration for the thoughts, memories, and dreams of mankind. The binding principle in this integration is the daydream. Past, present, and future give the house different dymamisms, which often interfere, at times opposing, at others stimulating one another.

In a postcard to Karl Priebe early in 1949 she referred to her new work as “quite different I think.” Whether or not this work appears distinctive in retrospect, the work of the late forties does evidence interest in themes which seem to relate directly to the particular circumstances of her life. In Indecision, a blindfolded Abercrombie stands, like Hercules at the crossroads, between the familiar closed door (now isolated in a moonlit landscape) and hill dominated by the tower-rook that appear in many of her works. The choice before Abercrombie, between love (indicated by the heart on the gloveclosest to the phallic tower) and self-protection (the door, even in isolation from the room, communicates fortification), is further illuminated by Abercrombie’s rare discussion of the meaning of a related work.

According to Abercrombie, the two tents in Between Two Camps of 1948 represent her marriages; she was divorced from Livingston and married to Sandiford in 1948. Like her interiors, then, these enclosures represent psychic space. This kind of shelter also becomes the focus for a theme explored a number of times in her work, in which closed tents are grouped around the base of a hill, often called “Encampment.” The tent is, however, a temporary and ephemeral refuge; it is tenuous and undependable. In Between Two Camps the white flag of surrender on the tent representing the marriage to Livingston is countered by the solid white stairs adjoining the black (Sandiford) tent on which the artist, waving a triumphant pink pennant, stands. But the stairs, however solid, lead nowhere: either down the same way she came or off the deep end into oblivion. The kite which separates the two camps may represent another thwarted attempt at communication; “kiting,” according to Frank Sandiford, was a colloquial expression meaning to send a message.

Two small pictures, Dilemma and Serpentina, both of 1947, repeat these themes. In the latter a pink-clad “Snake Lady” stands in a barren interior faced with the choice between a staircase which leads nowhere or two tightly closed doors. The solitary figure in Dilemma is faced with the same non-functional stairway in a characteristic moonlit landscape. Doubts about what can be expected from marriage are also seen in Bride, from 1946. Abercrombie, dressed in traditional marriage garb, walks along a barely visible path in a barren landscape to a tiny white church in the distance; the single spiky and barren tree is the only other element in the landscape.

If we return to Indecision and look at it with these ideas in mind, we can see the painting as an expression of Abercrombie’s struggle to make connections. We can see the tower on the rock as an expression of the union of male and female for which she yearns; it recurs in almost the same form numerous times in her work, for example in A Game of Kings. The close proximity of the door and geographical distance of the tower and rock again mitigate against Abercrombie’s success in forging connection. In fact, The Courtship of 1949, which includes a rare male figure clearly identifiable as Sandiford, conveys this in a poignant way. Abercrombie stands, arms raised in the air, as a masked Sandiford points a gun-like finger at her. Abercrombie claimed that she was the last thing that Sandiford, a small-time criminal before their marriage, ever stole. In the dark distance a tower-lighthouse on a low rise behind Abercrombie and a low sliver of moon behind Sandiford are the only things visible. Near Sandiford’s feet is an owl, near Abercrombie’s a shell. The shell is another kind of enclosure; here it is a reference, like the door in Indecision, to the protection Abercrombie needs, even while craving closeness.

Other images conveying confinement emerge in the forties. As early as 1943, Abercrombie began painting a theme she called “Self-Imprisonment,” in which she is facing the barred door or window in the single intact wall in a structure, thereby creating her own prison. A theme she called “Snared” or sometimes “Snagged” make its first appearance in 1947. Here she is tenuously attached by the long train of her dress (or sometimes a blindfold) to the wall of a room or a single door in a landscape. Again, her restraint is self-imposed, a crucial component of her lack of freedom.

If Abercrombie’s rooms are indeed depictions of psychic space, then her painted exteriors are equally telling. Abercrombie frequently protects the house by fortifying it, leaving out windows or doors, or rendering it inaccessible, as we see in the White House and Pump of 1945. The small white house nestled in a group of hills can only be reached by a long path and is shielded by spiky trees. The block house in 1945’s The Parachutist is also situated at the end of a long path and has a single door piercing its flat facade. The house in Reverie, the object of the reclining Abercrombie’s gaze, has no openings at all.

An exquisite variation of this is the Lonely House of 1938, done for the WPA. The house is a perfect Halloween image: an old building, isolated in the landscape, flanked by a leafless tree. In the deep blue sky, clouds partially cover a full moon, giving the sense of an impending storm, as well as night. The house itself, a tall, narrow, red-brick structure with a slanted roof, has not one but three doors, all closed tight like the doors in her interiors. Most importantly, however, none of the three actually give access to the house.The painting is a statement about the protection Abercrombie needs and has from the world: her seeming openness and accesibility hide a strong, impenetrable fortification. The sadness that pervades the painting derives from the conflict between the desire for openness and the inability to achieve it.

When she married Sandiford on December 31, 1948, at the home of friends Dolf and Emma Loeb, she entered a period of great inventiveness and productivity. In late 1948, she wrote Karl Priebe that she was “painting like crazy,” and indeed had some of her most productive and successful years in the late forties and early fifties. She continued to participate regularly in shows at the Art Institute and the Renaissance Society of the University of Chicago, and began to show again in galleries in Chicago and elsewhere. She had her first one-woman show in New York at the Associated American Artists Gallery in 1946. Of the fifty paintings exhibited at least half were sold. In 1951 and 1952, she had shows at the Edwin Hewitt Gallery in New York, a bastion of American Magic Realist artists,46 at the Bresler Gallery in Milwaukee, and at a number of galleries and the Public Library in Chicago. In 1952, a particularly prolific year, she had five one-woman shows and participated in four group shows; she produced in excess of 125 paintings, an impressive figure even if we qualify it with the fact that some of the works were very small in scale.

In 1951, she began making tiny paintings which she had mounted and made into pins. These were highly salable items which had subjects drawn from her established repertoire of motifs: self-portraits, still lifes, cats, giraffes, the tree at Aledo. She began exhibiting at the annual outdoor art fair in Hyde Park from the time of its inception in 1947, perhaps associating it with her enormously positive memories of the Grant Park Art Fair. Setting her work up against the side of one of the three old Rolls-Royces she owned at various times, she became a character associated with the fair itself. In addition, she exhibited work at other local summer art fairs.

One important new theme emerged in the fifties, when the Hyde Park neighborhood where Abercrombie lived became the site for urban renewal. It was common at that time to surround demolition sites with the doors taken from the building being torn down. Abercrombie was fascinated with the way these doors looked and they provided her with the only urban subject matter she ever addressed. Rather than being a departure from the typical imaginatively motivated image, these doors are closely connected with earlier images, particularly the interiors, the “Snared” theme, and images like Indecision, in which we see a door in isolation. The Hyde Park Demolition Doors resonated with an already existing interest in doors which, as we have seen, have great symbolic significance in her work. Doors arranged in this way also form another kind of enclosure for Abercrombie to investigate. In this theme, like many others, she has magically transformed reality into something strange and memorable.

While Abercrombie was not a great traveller, she went frequently to Wisconsin to visit her friends Karl Priebe, Dudley Huppler, John Wilde, and Jerry Karidis. She spent a short time in New York and in Provincetown, Massachusetts (where she worked and had a small show), during the summer of 1935. During the forties and fifties, she went to New York for openings of her own shows and to visit dealers and make contacts, but Chicago always remained the center of her world. Abercrombie’s Midwestern roots were important to her; unlike many artists, she does not seem to have desired a trip to Europe, despite her language skills and her particular interest in the French language. Exotic foreign lands held no attraction for a painter who found sufficient material for art and reflection always close at hand.

By the late fifties, Abercrombie’s decline had commenced. The health problems that left her almost incapacitated by the end of her life had begun to emerge. Her second marriage was failing, her artistic production dwindled, and her social activity waned. Not surprisingly, her penchant for small-scale painting increased until the bulk of her work was not only tiny but painstakingly executed and enormously controlled and restricted. She began to parody herself, doing variations on earlier works in a bright, slick but brittle style. Many of the numerous still lifes which she began to make in the fifties containing eggs, leaves, shells, dominoes, owls, and cats have a formulaic quality to them. The work prodaced in the sixties sometimes carries this to an extreme, although some of her most witty, humorous, and lighthearted work dates from this last decade of activity. The contraction of her physical world had its counterpart in the dryness and smallness of her vision as her life began to come to an end. At fifty she was already getting old.

Financial, emotional, and physical problems combined to make the last years of Abercrombie’s life extremely difficult. By 1964, when her second marriage ended, Abercrombie was also ill and had suffered financial setbacks. She began to withdraw; eventually she became an invalid, confined to one room of her house, her world as circumscribed and small in actuality as she had always depicted it in her paintings. Old friends found it harder to come to her, the parties ceased, and while she still remained the center, ruling from the house on Dorchester, the territory she controlled was severely limited.

She always felt her mother rejected her because she was ugly—she was not her mother’s idea of what a delicate, feminine little girl should be. Critic and dealer Katharine Kuh referred to Abercrombie’s perception of herself as ugly on several occasions; both Dinah Livingston and Wendell Wilcox emphasized the importance of this feeling, Wilcox suggesting that a true understanding of Abercrombie revolved around the issue of her self-perceived “homeliness.” “I paint the way I do,” she said in 1972, “because I’m just plain scared. I mean, I think it’s a scream that we’re alive at all, don’t you?” Her work, like her life, was a constant repetition of the same struggle without resolution.

In 1976, her long-time friend Karl Priebe died of cancer, following a retrospective exhibition of his work. The loss of this friend was significant, but it had greater meaning to Abercrombie because of her own physical decline. She suffered from pancreatitis, severe arthritis, and complications of these conditions aggravated by her inability to give up alcohol; she feared that her own end was near.

Abercrombie, however, was to have a final party. In February 1977, a large retrospective exhibition of her work was mounted at the Hyde Park Art Center.52 The opening, which took place during a blizzard, was an echo of the famous Abercrombie parties of the past. Confined to a wheelchair, Abercrombie reigned from the center of the room, receiving her many friends against the background of a live jazz performance led by Cy Touff. Once again, the queen was holding court and Abercrombie was in her element.

At the same time, she was preparing for her death. We get a sense of concern for her place in history very early. She saved drawings she made in college art classes and kept fairly elaborate records of her work through about 1960. Most importantly, however, she kept a selection of her best paintings and provided in her will that they be given to museums or other not-for-profit organizations at the time of her death. When she died on July 3, 1977, the house on Dorchester was filled with first-rate examples of her work from each period of her career, many of which are in this exhibition. She even tried to buy paintings back from collectors, and sometimes succeeded. Karl Priebe, who owned a number of Abercrombie’s paintings, was urged to return some of them to her before his death.

She never overcame, however, the feeling that she was homely, unloved, and inadequate. In fact, it was probably the source of the almost twenty-year alcoholic decline which ended in her death. But, in the last and greatest paradox of her life, she managed to compensate for her feeling of deprivation through her art and her creation of powerful personae. These gave her the tools with which to face and master her world. By ensuring that her work would continue to be seen after her death, Abercrombie exerted control over that world one final time.

Published on the occasion of

Gertrude Abercrombie

August 9–September 16, 2018

Karma

188 East 2nd Street

New York, NY 10009

Organized with Dan Nadel

Published by

Karma Books, New York