Gertrude Abercrombie, published by Karma, New York, 2018.

Download as PDF

View Gertrude Abercrombie here

Back in the day, the always-imperiled composition of the neighborhoods surrounding great urban universities in the United States—Cambridge, Massachusetts; Berkeley, California; Morningside Heights, New York—not only offered what these institutions required in terms of inexpensive faculty and student housing and affordable shopping and restaurants, they also accommodated, and for several decades even fostered, various bohemian communities. These neighborhoods provided wonderfully marbled havens for members of the Lost Generation, Wobblies, communists, Trotskyites, beats, beboppers, folkies, and hippies galore—as well as hosts of non-conformists who didn’t identify with a cause, an art form, or a tribe, but just lived life as they saw fit in a social and cultural DMZ that tolerated and sometimes embraced them.

Gertrude Abercrombie, with Karl Priebe (left) and Duddley Huppler. Priebes residence in Kalamazoo, Michigan, c. 1944.

Home to the University of Chicago, leafy, low-rise, low-rent Hyde Park with its double, triple, quadruple-decker apartment buildings, generally modest townhouses, wide alleyways, vacant lots, sparse street traffic, secondhand bookstores, small jazz clubs—despite the ban on bars close to the campus, the most notable of these was the Beehive on 55th Street—and racial fluidity was just such an enclave for generations of exceptional people from the 1920s through the 1960s. Thereafter the university promoted “urban renewal”—rightly called “urban removal” by low-income people of color and other real-estate “undesirables” it drove out—and the balance shifted definitively in favor of institutions and housing speculators, whose major clients were people with expensive lifestyles but not necessarily imaginative or interesting lives. But as everyone knows, such is the predictable cycle and dismal legacy of gentrification.

Nevertheless, those existential improvisers who did have compelling or at a minimum compulsive lives, and who were lucky enough to own their homes or have indulgent landlords in no hurry to trade up, held on for as long as they could. Gertrude Abercrombie was the child of itinerant opera performers from the Midwest whose travels with an opera company before World War I took them to Europe and back, where they settled in Chicago. Abercrombie thus acquired a gift for languages, and an ear for music—in addition, one surmises, to an Oedipally-tinged allergy to classical music that prepared the ground for her affinity for jazz—as well as the habit of living beyond her means, although she did so with an ingenious theatrical flare that made the most of the least. In her immediate domestic environment and in the decor of her paintings, that flare entailed stylizing decrepitude. In the former setting she sustained a salon of lost souls in the manner to which she and they had become accustomed. Yet if anything, Abercrombie was at once a gamin and a grande dame in the wrong place at the right time. As such she was a typically atypical figure within her motley cohort, a position she retained until most of that group had died off and she remained largely alone on the parlor floor of her domain until her own death in 1977.

Her house, a well-worn but still elegantly imposing four-story brownstone affair with a broad stoop, stood on South Dorchester Avenue just south of 57th Street, one of Hyde Park’s main arteries. At any rate that is what I remember, since I lived nearly the same distance from 57th Street on Blackstone, a block east of her. Most kids, and not a few adults in the neighborhood, generally kept their distance from the looming facade of her manse, over which hung an aura of mystery. What irresistibly piqued our curiosity—mine at least—were the cars that were parked out front. After all, I am thinking back to the mid- to late 1950s and early 1960s, when most college professors and the few students who could afford them drove late model Ramblers, secondhand Chevrolets, Fords, and Buicks, and, in the spirit of the times, the handful of relatively cheap foreign cars available. Of these the Volkswagen “bug” was unrivaled in its popularity despite—for a community full of pre- and postwar refugees, many of them Holocaust survivors—its origins in Nazi industrial “progress.” Just imagine Bruno Bettelheim and Hannah Arendt walking down the block with these reminders of Hitler’s Germany hugging the curb. All the more jarring, though, were the immense mid-1930s Packard touring car with full running boards and the still more majestic Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost that were paired in the street at the foot of Gertrude Abercrombie’s front steps, two luxury vehicles that should have been garaged in the back, but weren’t.

However, they did have a caretaker who spent days polishing them in preparation for taking the lady of the house out for a spin in the neighborhood. He was impeccably groomed, as a chauffeur should be—which is why that’s what everyone assumed he was, even though such a vocation, unsurprising on the posh North Side, was a distinct anomaly on the funky South Side—with short salt-and-pepper hair and a mustache (here my imagination may be filling in the gaps in memory, but that’s fine to the extent that it fleshes out a persona the man was plainly striving for) and a stern demeanor akin to that of a military man. Certainly, it was with the bearing of a manservant that he drove his mistress around town: he in front of the Rolls, for that was the car in which she made her occasional appearances, she in back looking like nothing so much as a cross between Morticia and the crazed grandmother in Charles Addams’ cartoon albums, then much in vogue and so probably an element in her unconscious or semi-self-aware mode of role playing.

Being a boy, I wasn’t privy to the peculiarities of that particular household, although with my job washing floors and windows at one of Hyde Park’s bookstores I was a junior varsity member of a bohemian set that was every bit as mixed socially and sexually as Gertrude Abercrombie’s cenacle, and far from ignorant of the possibilities that existed. But from the memoirs of August Becker, who was her intimate and his, I would gather that the man in question was not in fact a manservant but her man: husband Frank Sandiford.

What appeared to confirm that status was the explanation he gave me for the cars when I finally became bold enough to ask. He told me with considerable relish that he had been a high-class second-story man, a quaintly genteel way of saying burglar, that even then was totally in keeping with the studied anachronism of his form of vernacular dandyism. Before becoming a guest of the state—a similar usage—he had put much of the proceeds of his jewelry thieving into these two deluxe automobiles, where no one could get their hands on it and few would think to look. He led me to understand that he worked alone and that he had an arrangement with the Chicago mob, to which I assume he paid tribute, that permitted him to operate without interference. Once he had paid his debt to society—yet another cliché of the life of crime—he reclaimed his treasures and devoted himself to their maintenance.

Some of this may be true (August Becker confirms that Sandiford had been sent to prison several times and was at risk of a life sentence if he was convicted of any further felonies), or all of it, or none of it. In any event, in a town that worships its hoods and celebrates Saint Valentine’s Day with a unique sense of Schadenfreude, the mystery man and his cars not only added mystery to the aura of the principal occupant of the house on Dorchester, but grit as well.

Another layer of urban actuality that accrued to Abercrombie’s sometimes Blanche Dubois-like profile in the “small world” that was Hyde Park from the 1930s through the 1970s—it still is a small world, but a less mottled, more homogeneous one—was a result of her passion for jazz and her close acquaintance with many of the greats of that era who performed at the Beehive and other clubs deep in the ghetto north and south of the neighborhood. Photos of Abercrombie with these musicians—Sonny Rollins, next to whom she sits wearing a Stetson while he, sporting a mohawk, plays a wind instrument as if it were a peace pipe (a game of Cowboys and Indians softening the hard edges of the black/white dichotomy which were nowhere so hard as they were on the segregated South Side of Chicago) and Dizzy Gillespie warmly hugging her at a party in her house, just to cite two of the most prominent—make it clear that she was a true friend as well as a loyal fan. As such, she joined the sorority Miss Anne— the namesake of a sisterhood of mostly well-born white women who gravitated to the artists, writers, and jazz men of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s. These women sought “adventure” but also a community outside the confines of the often straight-laced and stultifying milieux whence they came. For them the socially uncharted territory between the races offered freedom, albeit a freedom available to them by virtue of their relative wealth and light skin, but hard won (if achieved at all) by the talent of their darker-skinned counterparts. Still, the insurmountable inequalities, latent tensions, and corrosive mistrust inherent in crossing the boundary from either direction are not apparent on Abercrombie’s face or the faces of her companions. Whether she was simply unaware of their existence and the jazz men simply ignored an ache they almost certainly felt, or whether collectively they had transcended their differences is impossible to know for sure. Suffice it to say that in those days and that place, bohemia was an omnium gatherum of misfits, and to whatever degree they could, those who fit in nowhere else fit in there, and, sensing contingent if not utterly improbable solidarity, recognized a degree of kinship with everyone else at this come-as-you-are party.

That said, the thing that most set Gertrude Abercrombie apart from other oddballs in the neighborhood—and piqued my youthful interest—was that she was a painter. Although writers could be spotted in the area (Saul Bellow, Richard Stern, and Norman Maclean were the local novelists), there weren’t many artists around. Rainey Bennett, mostly known as a children’s-book illustrator, was another, and, like Abercrombie, he exhibited regularly at the chicken-wire Hyde Park Art Fair in the playground and parking lot of Ray School, which, in combination with Hyde Park High, were the public schools to which “townies” sent their kids, while faculty brats went to the John Dewey’s experimental University of Chicago Laboratory School.

Given the university’s “hypertrophied logocentrism”—terms of that kind epitomize the local academic dialect—words eclipsed images so completely that anyone who devoted themselves to the latter activity was ipso facto deemed strange if not deplorably unsmart. Even Gertrude Stein, who visited the university in the 1930s when its President of the University, Robert Hutchins, and his Cardinal Richelieu, Mortimer Adler, committed the college to rigorous scholasticism to the exclusion of all else, couldn’t get a word in edgewise when she challenged the powers-that-were on the virtual absence of works of fiction from The Great Books published and promoted by the university.

So, the other Gertrude—Abercrombie—was even more of an outrider among the chattering classes that huddled around this mostly white, in the main highly educated, and comparatively comfortable enclave in the heart of the otherwise bleak, starkly ghettoized South Side of Chicago. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, Abercrombie had an eye for bleakness, indeed a romance with it. Maybe it was the carryover from the Great Depression, when Magic Realists took to portraying a vacant, tattered America that was the shadowy, quasi-Surrealist twin of the robust can-do populism of American Scene Painting as codified by Thomas Hart Benton, who had visited Paris and briefly frequented Stein’s household, only to rebel against her on returning home and reject everything modern and French in an inward-turning vortex of formal backsliding and symbolic chauvinism. All too often, Magic Realism also suffered from nostalgia and provincialism, but in the hands of painters like Abercrombie the result was an American Gothic quite different from that of Grant Wood, but closer in spirit to the next generation’s masters of genteel misery and woe. As it happens, many were illustrators, Charles Addams being one, Edward (or, as he sometimes signed himself, Edweard—a self-mocking variant on Ed-weird?!) Gorey being another. But then Surrealism, which was the tap root of Magic Realism, is basically a storytelling or symbolist mode of expression. That put its practitioners—native Chicagoans fussy Aaron Bohrod and fire-and-ice flamboyant Ivan Lorraine Albright chief among them—“on the wrong side of history” as defined by postwar formalism in New York. Of course, its academic exponents eventually took over museums and art departments everywhere, including the Second City, condemning artists so inclined to an obscurity greater than that of their iconography.

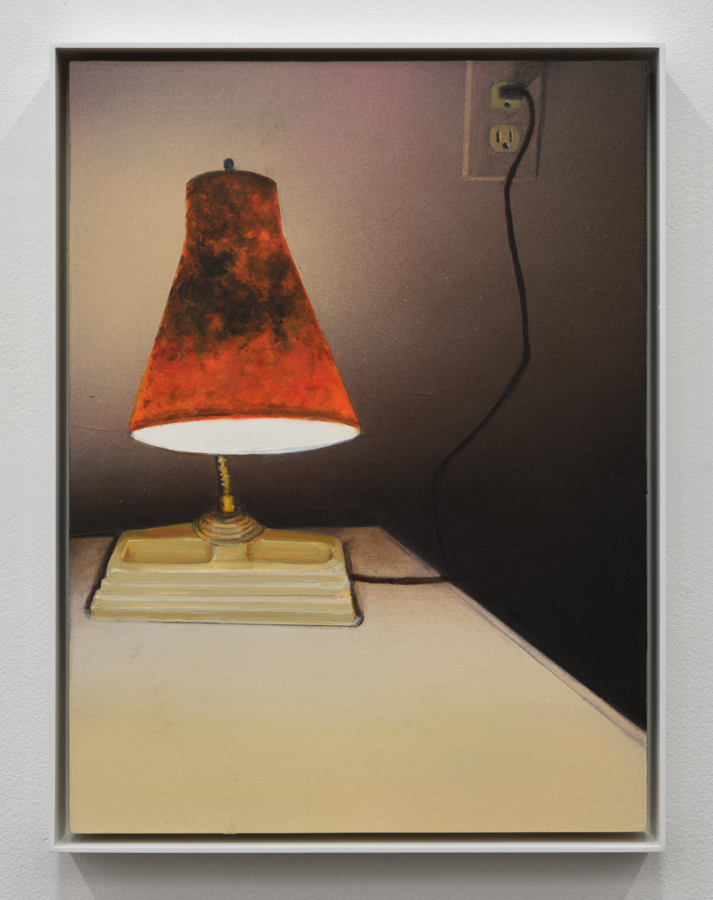

A singularly fey exponent of the same generally fey aesthetic (despite the fact that she feigned ignorance of artistic trends or the work of other artists), Abercrombie had a special talent for stripping the standard emblems of loss and longing in which Magic Realism specialized to the barest of bare bones. Painterliness per se had little role in Abercrombie’s art. Everything was conveyed by the prose-poetry of her consistently uncanny musing. Hers was a dreamland of gnawing disquiet in a region of unchanging plainness and austerity; a place where quotidian reality constantly oppresses but where things regularly go bump in the night, and where it seems from Abercrombie’s perpetual grisaille twilight palette that night is never far off. Playing hide-and-seek with her obsessions, and bottle-bottle-who’s-got-the-bottle with her friends behind the curtains of her lair while parading like impoverished royalty through her bohemian duchy as it gradually slipped into bourgeois normality, Abercrombie was “a character” who attracted those who needed “proof of life” in the most conventional periods of the 1950s and 1960s, but outlived the social ecology that would have brought other eccentrics into the open and allowed them to thrive. We’re facing a similarly oppressive normalization of the status quo right now. Maybe Gertrude Abercrombie’s moment has come again. If so, it’s a pity that she’s not here to enjoy that resurrection, though it’s good for her artistic reputation that she is no longer here to upstage her fragile, claustrophobic, memorably mid-American Gothic work.

Published on the occasion of

Gertrude Abercrombie

August 9–September 16, 2018

Karma

188 East 2nd Street

New York, NY 10009

Organized with Dan Nadel

Published by Karma, New York

Edition of 1,000