September 12, 2020

Henni Alftan published by Karma, New York, 2020

Download as PDF

Henni Alftan is available here

Henni Alftan is a Finnish-born artist who has lived for about twenty years in France, where she studied art. For a painter, France is not ideal. Its avatar, Marcel Duchamp, preferred verbal metaphor and visual games to a single skill. He also exemplified a culture whose life-support system is quotidian comfort, easy eroticism, and intellectual discourse. But as a foreigner, one can both let go of rules one was brought up with and not wholly submit to those of an adopted country. Even if you’re fluent in the second language, one can turn it on and off to avoid the stress of the pervading mother tongue’s requirements. These benefits are liberating for those who like being foreign.

Alftan had thought about studying art in England but settled on France, which is also much less expensive. In France, where I taught art for over twenty years, students are asked to explain and defend their work as it’s being perused by faculty members. Apparently, Mademoiselle Alftan was able to do that, earning a bachelor’s degree at the Villa Arson, in Nice, a bastion of conceptual art, and a master’s degree at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where one is largely left alone to develop a method or a practice that the entrance examiners found worthy enough to accept. Few of her fellow students in either school were painters.

Her artist statement in English, which is a bit more straightforward than the French one, clearly describes her method of picture-making, about which she was expected to be very conscious:

These pictures are the consequence of my observation of the visible world and its representation. Small perceptions of the everyday merge with reflections on looking, painting and image making: the motif of my works is equally painting itself, its history, the paint as a physical substance, the tableau as an object. Painting and picture often imitate each other … I seek to give only the necessary amount of indications … There are no photographs on the walls in my studio … My paintings are constructions of lines, colors and proportions … predetermined in the sketch, the plan. But my images are not new. I did not really invent them. It is as if they were already there.1

But Alftan does come from a northern country. A country driven by practical concerns because of a severe climate, limited light, a highly developed education system, an enduring but friendly population of 5.5 million, and formidable neighbors: Russia to the east, Norway and Sweden west, and Europe south, which might make friendliness a cultural necessity.

When I think of Finland (not having been there), into my mind drops Marimekko’s wide bands and curved shapes, the red poppies and strong colors in graphic simplicity. Could that be clarity vis-à-vis the long winter nights? (Mekko means dress; Maria was the designer’s middle name.) Finland’s most famous filmmaker, Aki Kaurismäki, an auteur known for his (wonderful) minimalist style, founded a surf-rock band called the Leningrad Cowboys just as the Soviet Union was waning. The band’s brilliantined swooping hair, shaped like fins, the pointy shoes and Fender guitars, with a trebly tremolo, were counterpart to a landscape drenched in the filmmaker’s unforgettable litanies about life and love in a world of snow and vodka. Kaurismäki’s Lynchian cool and his band’s independent insouciance, the borrowed gear and style of dress, seemed to dream of West Coast California not the west of the Eastern Bloc.

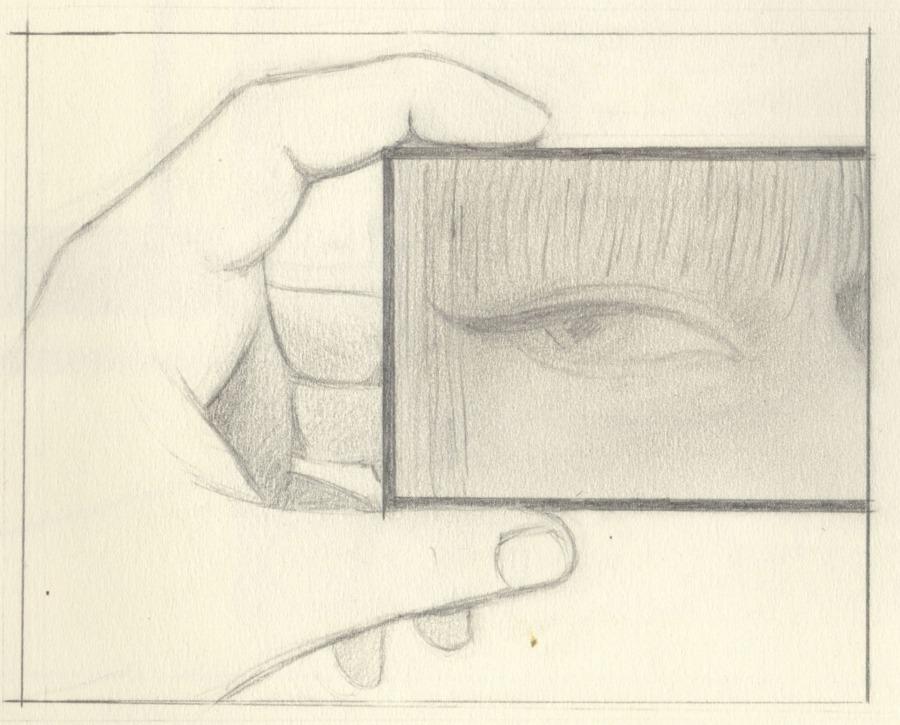

Henni Alftan’s outdoor paintings offer a crepuscular radiance. Interiors are framed in shadows and flat planes of color. Each one starts with a drawing. Her artist’s statement emphasizes “no photographs on the walls in my studio.” So, the paintings are life seen and transformed. They’re the size of normal windows, not large ones; none are the scale of a billboard or cinema screen, as was common in earlier generations of painters, certainly in New York. I thought of American Alex Katz, who is fifty-two years older and whose large, colorful figurative paintings and broad swaths of flat color, with faces reduced to simple shapes, came at the end of Abstract Expressionism’s defining years. He, too, synthesized photograph-like representation but avoided pictorial narrative. Alftan recalls Katz at a much smaller scale and through a different lens, if not two lenses, one normal and the other skewed, like a very toned-down Magritte. If connections are demanded, she might be a latter-day descendent of Katz and Magritte.

The night I was contacted to write this, having read her statement, and thinking about what to say, at two thirty in the morning I was awakened by a dream. The dream involved a very large stuffed alligator in a very yellow room and a furry tarantula that I could not see, but knew was there. I knew because I’d had this dream before, the spider being a recurring incubus I’ve since gotten rid of. Almost instantly my nervous copilot stirred me to wake. Flailing in the darkness, my heart racing as if I’d been running, I hit the light switch. Simultaneously the earlier dream compressed in its entirety. In lucid dreams, one is aware of dreaming. Escaping from the earlier one, I had to catch my breath. Lying back down, after a few minutes the word coherence came to mind. The earlier dream presented itself as a coherent story, complete in itself, a sight unseen in reality but revisited in a dream to get out of.

Art that looks real doesn’t have to be real, it only has to be coherent, and it doesn’t have to be true, only relevant, if only to itself. Alftan stated that her paintings are based on observations and perceptions, “as if they are already there.” Each is visually coherent and freighted with relevant familiarity. There are no alligators or spiders, but there is a coherent and relevant “way of seeing,” to borrow John Berger’s phrase and his point that ways of seeing are driven by culture, the nongenetic transmission of information. Alftan describes in her statement her conscious approach to painting, via perception and the history of picture making. But what gets her paintings made is the hand-eye coordination she has inculcated into a process of making them presentable. Ernest Hemingway, in A Moveable Feast, remarked on Gertrude Stein’s statement that a work—she was talking about his writing—had to be accrochable, French for hangable.

I called Henni the day after the dream. She told me she knew when she was five that she wanted to be an artist. Every five-year-old may be an artist but few are going to achieve public exhibition. She also said that in Finland people call her works Continental, while Parisians call them Finnish. Let’s call them international contemporary art that focuses on picture making. In this regard, Henni Alftan’s paintings are pictorial, meaning fabricated, rather than imagistic, or a visual cliché. Images are things one expects to see, which can be altered by suggestion, or even by force, say through gossip, innuendo, or fact. Pictures are made to be seen and interpreted however one wants.

The philosopher of consciousness Daniel Dennett likes to demonstrate how sight can be influenced by the unconscious mind’s magic. Things are missed because the unconscious mind’s magic. Things are missed because the unconscious mind corrects in preference for the expected. The apogee of human vision, according to Dennett, settles on a point about the size of a thumb at arm’s length. So the mind can inflate what we think we see in the peripheries, such as the wrong person in a particular place, or something suddenly coming into view. And when something catches our eye, such as the erotic, the unusual, or the extreme, our focus shifts toward it. This is when sight is revisited, which, it seems to me, is the subject of these paintings.

Humans began decorating cave walls at least forty thousand years ago. Primary images were the animals they hunted, their own hands, stick figures, and wavy lines, which might represent water. Yet culture took off when people settled down and built walls, which they then covered with frescoes and varieties of decor. In the Renaissance it became common to paint on fabrics stretched into the window shapes. Now we have television and magazines distracting minds and feeding our memories and experiences.

Painters now compete with disposable images. They might also look for the things we overlook in an environment that writer George Trow called “the context of no context.” Trow suggested we live in a world of expected wonder, whether looking at a skyscraper or a film.

I get the impression that Henni Alftan looks carefully. Some of her paintings go in very close. Some show a cultural distance, say at a distance that one can talk without raising one’s voice. Some images are filtered through a fence, or a train or airplane window, or through raindrops, or a pair of glasses on a table, or from the POV of the tabletop on which something is observed. Another feature is the variety of patterns. Language and experience are driven by pattern thinking, which enables people to create the generalities they can more easily repeat—and get wrong. Intricate patterns appear in Alftan’s portrayal of hair, fence wire, drops of water, flowers, fabrics, lace, grass, and in the straight and curved lines that are everywhere in her work. These patterns best reveal her skill, which is a person’s most counted-on human trait, and the one that can wow and create wonder in others. Otherwise, we complain about mistakes. Magicians, musicians, surgeons, carpenters, mechanics, writers, artists, and cooks rely on skill. Everyone does. Artists have to reconcile at which point a mistake is accrochable. Alftan knows where they are. We might not see them. Otherwise, the major elements are the generic faces, bodies, legs, rooms, books, shelves, doors, cups, gloves, hands, and legs. The major elements are the “already there” backgrounds against which she imposes the visual twists that she makes us conscious of, and that a philosopher of consciousness, like Dennett, might say generally go unnoticed.

Dennett likes to demonstrate how much the eye can miss, particularly in slight changes to a familiar image. He relates consciousness to a magician’s bag of tricks, only the mind doesn’t have access to the tricks, just to the illusion that the brain foists on us, which we may need to get through life. Alftan focuses on things we might see but have missed. Maybe this is itself a reason that art even exists. Her bag of tricks is revealed in the coherent way she composes a picture. None of them are clichés. She has enough of what musicians call chops, which they get from practicing, and she might have earned by starting so young. Not every painter is capable of painting parallel lines. Michelangelo boasted that all he did was chip away at the unnecessary parts to get to his subject. Barnett Newman and Frank Stella used tape. The only works that Minimalist sculptor Donald Judd made with his own hands were the plywood sculptures he could cut himself. Yet all artists’ works are based on observation and perception. Alftan is a painter who uses the visual language of the “already there,” which she transforms. But even she can’t know where her paintings will lead her. And what could be better?

1 Henni Alftan, Henni Alftan (Aubervilliers: Is-Land Editions, 2019).