October 5, 2021

Henni Alftan, Dike Blair Karma, New York/Various Small Fires, LA, 2021

Download as PDF

Henni Alftan, Dike Blair is available here

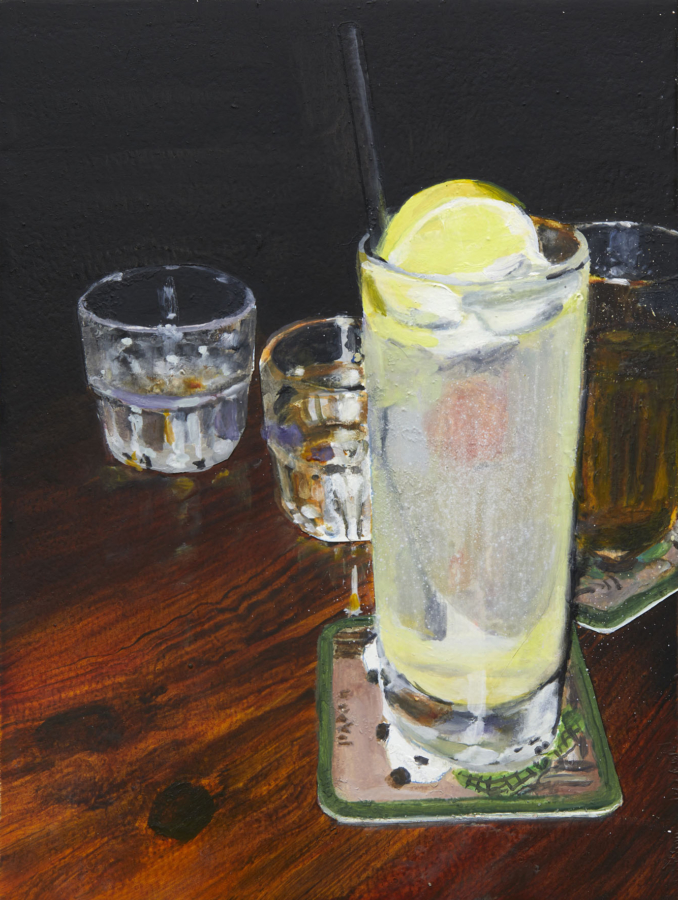

Dike Blair, Untitled, 2020, gouache and pencil on paper, 10 × 7½ inches (25.4 × 19.1 cm)

When Karma called me late last spring to ask if I’d be interested in writing an essay for a small exhibition featuring the American artist Dike Blair and the Paris-based Finnish painter Henni Alftan—a collaborative venture the gallery was in the process of planning with the directors of the Los Angeles– and Seoul-based gallery Various Small Fires, for their Seoul space—my reflex was to say no. I write with enormous difficulty, even under the best of circumstances, and unlike many of my art-world peers, I was still in New York City, wrestling the emotional isolation and remote teaching imposed by COVID-19 and the more incendiary thoughts and feelings incited by the political events that had pulled me out of my dutiful quarantine. It was hard to imagine myself sustaining a focus on the inner workings of a single artist’s efforts, never mind an exhibition I would experience only via a digital PDF checklist. And while I have followed Blair’s work with curiosity and delight since the early aughts, and developed a deep fondness for his recent small gouaches and oils, it was not at all clear to me what they might gain from new writing. Blair’s paintings, I thought, as I weighed the prospects of writing, are precisely the kind of paintings that, at least for me, repay repeated and long looking without any real need of explication. Alftan’s paintings were still new to me: I’d been much taken, and more than a little confounded—a good sign—by the few that I’d seen in a fall 2019 group show at Karma (with Alftan, Matt Hilvers, Ruth Ige, and Andrew Sim); but I felt I needed more first-hand experience of her work before writing, something I didn’t think likely, given the ongoing lockdown. The afternoon that Dugan called happened to be one of those uncannily crystalline late spring days, in which the very un–New York cerulean sky served as testament to the positive impact of a few months of near-zero air and auto traffic—a surreal blip in a season of gloom with the power to change moods, if not minds. A good omen, I thought. More abstractly, I began to consider the intimate, insular, and complex psychological qualities these two artists shared as a subject newly inflected by the pandemic and frightening overwhelm we were living through. The insistent formal and material emphases they also shared, albeit in radically distinct manifestation, along with their common eschewal of any overt reference to social context, became an interesting challenge. Racing thoughts to ponder on a street corner, phone in hand. I agreed to write.

The immediate prompt for my decision, however, was more personal. For several months during lockdown, I’d been “tuning in,” daily, to one of Blair’s singular cocktail paintings—an especially inviting Tom Collins (Untitled, 2020), which I’d stumbled on in a Karma online “viewing room,” trolling for art around which to build my newly remote university art school seminars, and cursing the sensory deprivation imposed by the screen. (I’ve never been one to delight in the digital.) Blair’s gouache defied the odds. Even minus the tooth of the paper and any sense of the deliberate small scale I’d have registered were it set against a big white gallery wall—exacerbated by the fact that the viewing room featured an enlarged crop of the gouache—the painting exuded a visceral sense of coolness and wet; it almost literally glowed. From a purely formal vantage, Blair’s laying down of transparent color washes—pale pink and yellow surrounded by a counterintuitive gray—kept me staring. There are other details in the painting that particularize the occasion it records while also adding to its formal strength: a couple of empty glasses and one half filled, also on the bar, register a prior drinker’s uncleared mess or a third or fourth drink for whomever ordered this new one. The bright green lines rimming the square coasters and bits of black and white (pandas?) pictured on these; the play of these squares against the circular glasses and conspicuously large lemon slice; the careful rhyming of whiskey or scotch, and wood grain: each of these things must have added to Blair’s sense of a painting-ready subject. Or were they added, I wondered? The quantity and quality of formal attention in these deceptively straightforward “genre” scenes all count. But, for me, what mattered was only the pristine freshness of the featured drink, not yet sipped, and the promise of that ever-welcome first-drink buzz—an effect Blair has talked about. For a while, searching the painting each day had become a kind of meditative act; staring at its complex palette, an ever-surprising visual mantra, shifted my mind to the concomitant pleasures of color and drink. The ritual viewing took on added importance for me during those peak COVID-19 months, because my elderly father’s health was failing rapidly, and my time was increasingly dominated by parent care and a situation I could do little to change. The painting’s visceral and associative effects yielded a great deal more than aesthetic pleasure. Until I was asked to write, I was perfectly content to experience these effects without finding words for them.

I received the checklist for the upcoming Seoul show with Alftan in mid-July, along with PDFs of numerous other recent Karma writings on Blair’s work and a substantial, soon-to-be-released monograph on Alftan, produced to accompany her upcoming fall solo show in Karma’s New York gallery. I’d begun to work out my thinking for an essay, based on what most mystified and held me in his recent paintings, namely, their light, and the curious directness and experiential specificity he managed to muster in his still lifes. I knew that Blair based these paintings on photos he took from his phone, and I’d learned through my reading on Alftan that photography had no part in her process. I was also looking for a way to write honestly about paintings I wasn’t going to get to see—Blair’s new ones—except online, which is to say, minus much of the formal “information” that might account for what I’d responded to in earlier work. Sussing out shifts between the camera’s default aesthetics and Blair’s carefully crafted interpretive borrowings and reformulations, through the digital displays that now served as our windows onto everything, excited me. Contrasting Blair’s embrace of the camera’s capture with Alftan’s assiduous eschewal of photo as source seemed an interesting approach to writing on these artists together, and one that might spare me repeating all that’s already been offered in accounting for Blair’s art. I wrote Blair in advance of calling, to ask some questions and share my idea. I wanted to know how he’d been faring through COVID-19 and I was hoping he’d agree to show me a few of his working photos, and the printouts that followed. I was fixated, especially, on the role that light played in his painting, and the myriad of means he contrived to convey its material presence and metaphysical residues. I was similarly caught up in Alftan’s obsessively hand-built paintings, and the slippery shifts she establishes between paint and image by treating the paint as structural unit, as well as medium. Blair replied to my questions the next day with characteristic generosity and care, and politely refused my request.¹

Here are answers to your questions:

First, whether you’d be willing to talk briefly about what you’ve been working on, if anything, during the COVID-19 “Great Pause.”

I’ve been working like crazy. Twenty-three gouaches and more oils. I’ll Dropbox you the whole batch.

Second is whether you might be willing to share images of any working photos for paintings in the show, or ones I describe in detail. (I can share a short wish list.) I’m trying to deal with the very specific confluence you manage—in your gouaches, especially—between the reliable real-life emotional charge at first sight of a drink and the particular pleasure of the buzz that follows, and your painting of that glow in color.

I feel like I might be wrecking your essay in progress, but I’d prefer not to share the working photos, mostly because the juxtaposition begs for comparison. When I have my wife into the studio, I remove the working photos because the fidelity is what she first examines (sometimes the photos are hers, so I suppose that’s a factor). The paintings are very close to the printouts I paint from. In advance of printing out an image, I Photoshop it a bit, sometimes correcting color. I almost always crop and distort the image slightly. Sometimes, though not particularly often, I’ll remove items in a still life that seem extraneous. I do take pleasure in capturing the photos’ light and color.

Paint application is another matter. With the gouaches, it’s more like dyeing the paper with multiple applications of transparency and allowing the paper to provide surface and texture (I don’t prime the paper for gouache, although I usually do for the drawings). The oils offer many, many more options, which is why I’ve particularly enjoyed painting them. There can be a kind of restrained impasto. The reflectivity of the surface can be manipulated. Usually I go for a kind of semimatte surface, but on a painting like the license plate one, I want more reflectivity so use more stand oil. Back to my reluctance to share working photos: I suppose one could call me a Photorealist since I’m rendering a photograph, but that’s not how I think of myself. When I take and edit images, I’m pretty conscious of how they might translate into paint, and what painterly technical challenges the image presents. The images are also fairly personal and have emotive content that I don’t associate with Photorealism.

You’ve said often that your formal decisions are made in the photo/s you take. But then you do such terrific things with the painting of the painting that I’d love to see what changes, what stays. Also what photos you might take and not use.

Simple formal decisions (everybody does this) do get made when I’m taking my snapshots, and then when I work on the computer, and especially when I determine what group of images I want to paint. I usually want images that demand different techniques so as not to bore myself. But I also want images that do beg formal comparison, and hope that some frisson arises from certain juxtapositions. For example, I painted Windows/Flowers for a few years. The windows engaged the paintings’ edges, generally being somewhat empty in the middle. Conversely, the flowers (or cocktails) usually direct the eye to the center of the painting.

I disagreed with Blair’s fear that the juxtaposition of photo to painting might incite a comparative search for fidelity, but he was right, of course, to refuse the photos. I didn’t want to kill the mystery. Still, though I appreciated Blair’s interest in the formal concerns he mentioned, I thought that the close comparison between photo and painting might yield a few surprises about his fascination with light, and about differences in the phone-camera and painterly registers of time. Much of my interest in Blair’s light came from my earlier experiences of his sculptural installations, and my fondness, especially, for the sui generis tableaux that preceded his more anthropomorphic, portraitlike “crate sculptures,” on which he often attached some of his gouaches. The sculptures I’d most loved played more as abstract, decontextualized landscapes, with physical lamps and light boxes. These were often painted with transparent color, set out with other minimal shapes and volumes—areas of carpet and platforms—and functional electric cords that drew funky lines between these, in ways that felt closer to ritual arrangement than any more programmatic minimalism. Blair dubbed these “Home Depot Minimalist,” while invoking the arrangements of Japanese ikebana and the humor and ironic remove of comic books to convey the disparate emotions and perspectives those sources summoned. I remember my first enchantment with these installations. They were the first works of Blair’s I’d seen, and they remain some of my favorites. Maybe the credit goes to Blair’s infatuation with ikebana, which was the antidote to his deep-seated punk and comic book nostalgia. There was a welcome shift here from noise to light, although the platforms and cords sometimes carried a vestige of performance and music. The pacing and spacing and play of shape, volume, and line; the careful modulation of light quality and color, contained and ambient; and the insinuation of bodily movement in, around, and through these tableaux anticipate Blair’s similar control of the elements he orchestrated on the flat surfaces of his later representational paintings. I loved the literal, material means he used to effect poetic textural shifts between rough and smooth, found and made, corporate and domestic. I loved his distinctions between the colors of incandescent and fluorescent lights, and the physical, ambulatory engagement they invited. I loved their offhand humor. And I loved the allusive, haiku-ish titles he gave these, like the melting snow is odorless, 1997–98, or some of, 2001. (He titled his first museum show—in 2009, at the Greensboro, North Carolina, Weatherspoon Art Museum, itself a compound installation—Now and Again.) As with any of Blair’s works, the affective impact of these sculptures gains not from any labeling of aesthetic procedure—we don’t need to think “minimalist” here any more than we need to think ”photo-realist” when looking at his paintings. The initial response they incite—mine, anyway—remains subliminal and wordless. I was delighted and moved by Blair’s channeling of this mash-up of sensibilities and by the canny equivalents through which he staged them. These are not works that change thinking, or make claims. Their appeal comes closer to that of a new acquaintance or fictive character whose unexpected mix of traits surprise and delight, suggesting some less accessible mystery. The pathos Blair so often summons in his paintings of the past few years has roots here. Blair has said as much. But he has also credited the photographs he works from, as in his comments, above, for inspiring his painterly reformulations of their light and color effects.

The comment that first pricked my interest concerning Blair’s use of his photos came from a conversation with the photographer Steel Stillman, in 2009, at the time of his Greensboro museum show:

The invested labor in the paintings slows down how the image gets read. Obviously a great deal of the pleasure in looking at paintings comes from decoding the sequencing of their making. Much of my pleasure in painting them is simply figuring out how to do it, how to get gouache to look like something. Perhaps there is some pathos embedded in the paintings, some residue of my repeated efforts to approach a photograph without ever getting there.²

What, I wondered, would it mean to “get there”?

I was thinking, too, of Blair’s paintings within the larger framework of our current maniacal reliance on digital photography as record—socially, personally, politically—and our distrust of its potential manipulation; and wondering what, if anything, they borrow from this. Tim Griffin, in an earlier Karma essay, pointed to the “interstitial” spaces and indexical time Blair builds into his paintings. He refers not just to the compositional sequencing in Blair’s time-specific still lifes, but the varying states of his painted object-subjects as records of experience: a cigarette stub as distinct from one newly lit; a fresh drink versus an empty or half-full glass; a plate of partially eaten oysters on ice. Griffin calls on a cinematic reference to make his point; specifically, the full-frame, stilled shots spliced between sequences of action to signal a pause for reflection. He was trying, I think, to characterize a quality of time he read as a subject, or sub-subject of Blair’s: a pause, or waiting; the processing of a before and after, in anticipation of something, unpictured, to come. The attention Blair calls to such times within time, and the painterly correlates he contrives for these discrete increments, are also what distinguish them from photos.

Helen Molesworth, in another Karma essay, offers an inspired analogy for the sensory satisfactions of a Blair painting: his talent for contriving formal equivalents for the “feel” of things that inform our experience of them. In lieu of detailed visual analysis, she describes, in terrific detail, the haptic familiarity of a certain “hook and eye” lock on the bathroom door of a favorite bar, presumably negotiated after a drink or two. My fixation has been on Blair’s long-standing preoccupation with not just pleasure, but light, and its part in particularizing the humble pleasures he favors as subject, without—and this is the feat—any moralizing. Blair himself regularly stresses his pleasure in pleasure: “I like pleasure in life and in art. That’s not a terribly complicated position, but any kind of moralizing about it would be.” I wanted to home in on Blair’s increasingly precise ability to find ways to paint a kind of domestically scaled “cocktail” luminism—an intimate reformulation of that expansive, idealized American nineteenth-century landscape painting as poltergeist, “flash,” gleam and glow—in the guise of still life, but with the range of effects and time-specificity of phone photography, and without any bloated claims to transcendence. Blair’s magic, I thought, had everything to do with the mystery he regularly set up by painting not just the light as light, or the ostensible subject, but their mutual dependence. Or maybe I have that reversed! The mystery in a Blair painting owes, I think, to the magic he musters through his finer and finer honed, intuitive formal decisions; and to his moves away from the auto-effects, however impressive, of the digital camera. Blair isn’t Rembrandt; he’s not even a capital-L Luminist or, for that matter, a conceptual Pop painter, like Ed Ruscha, whom he has acknowledged an interest in and comes closer to. He’s not alluding to God’s presence, or God’s presence in nature; he’s not seeking to “elevate” his subjects to philosophical or religious status, as Ruscha has said he does, by taking his “nonsubjects” out of context and repositioning them as subjects.³ Blair is working from the sites and stuff of his own everyday, and vacation, life—the stuff of phone photos—while wielding his paint- and color-filled brush with an intuitive, Tinkerbell touch. The light in Blair’s painting is everywhere and nowhere. It also tells time in ways that borrow, directly, from the photos he deploys. And if, to his mind, his paintings “aspire” to the pathos of the photograph without ever getting there, for most of his fans, the pathos he builds into his precise compositions and painterly effects is something those photos can’t possibly rival.

At the same time, the overall affective impact of Blair’s photo-based paintings comes close to what Roland Barthes ascribed to the punctum: that salient detail in a photograph that “touches,” or “wounds,” which is in turn contingent on the certainty that what is pictured did happen. Or perhaps I should say his paintings play as a punctum-in-reverse. Because, in Blair’s case, these details and effects are multiple, dispersed, and simulated in paint. Yet Blair’s apprehension of specifically photographic effects matters greatly. The intertwined celebration of leisure activity, snap-shot “instaneity,” and light in photo-inspired painting goes back to Impressionism. Blair’s painted light, I think, owes much more to the erasure of stroke and liquid glow of his nineteenth-century American trompe-l’oeil and luminist ancestors than to the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist optical division of stroke. He’s also a better colorist than any of them. The offhand elegance and poignancy of Blair’s compositions and layering of color borrow something from Manet: they share a restrained impasto and have a similarly compelling grasp of social pleasures. And, as with Manet, they are unapologetically subjective in their emphases. More to the point, and vis-à-vis Alftan, Blair’s paintings have the I-was-there, live-capture “truth” we now assign to the “selfie,” which keeps the pathos from veering toward sentimentality as it suggests that you and I, his viewers, could be there, too. An online video, slugged “Dike Blair and Marie Abma, Drinking Cocktails in Japan,”4 gets at the pinpointing I’m trying to suggest, as well as something of the offhand elegance Blair favors, and the strategic degree of remove in his painted tableaux. The video records a bartender in a Japanese bar, mixing an exotic drink that Blair and Abma—whom we hear, but don’t see—eagerly await. (It’s mostly Abma’s voice that we hear.) The bartender’s meticulous attention to every ingredient and step, and his deadpan refusal of facial expression, is punctuated by Abma’s closing exclamation, as the video ends: “Wow!” she says, “That’s the secret ingredient!” Once again, I wondered, watching, what photos Blair might have taken at that bar; what painting they might have become.

In lieu of any source photos, Blair sent me JPEGS for a few paintings he’d recently finished and especially liked. They were wonderful, even as JPEGS. He called my attention to the two types of composition he’d mentioned in his email: the edge-to-edge painting of a window versus the centered massing of some flowers on a bush. My attention, however, was focused more on the unexpected light suffusing one of the edge-to-edge paintings, a predominantly gray one of an unassuming, mostly closed, translucent window—another favorite Blair subject—in what turns out to be a Japanese men’s room, although, as is often the case with Blair, nothing in the painting says as much. (His recent paintings, unlike the “ikebana” sculpture, are uniformly untitled.) In this one, the window fills almost the entirety of a smallish, 20-by-15-inch oil on aluminum. The window is backlit, but undramatically—what you might expect when the view out was probably from a fluorescent-lighted bathroom. If the painting were simply of the dank bathroom grayness, it would be making a statement about bathrooms. Instead, Blair leaves a sliver of the window open—another favored Blairism—exposing the brilliant, daylit green of plantings outside, and “explaining” the excuse this gives him to paint a row of four muted green rectangles across the left side of the sliding window. We’re seeing the greenery between the vertical fence posts just behind it, through its beautifully calibrated translucence. Blair’s Tinkerbell touch in this painting comes from the perception he introduces of a glinting metallic grid that reinforces the window’s glass, achieved by incising the grid pattern into the paint. I know this because he told me; but, even in the PDF, I can read and feel that seemingly metallic grid as it cuts into the layering of paint. Any one of these effects—or, for that matter, Blair’s careful painting of both window latch and window handle; or the line of shadow that marks the recessed track on which one window opens against the other; or, or, or—might count as “punctum.” For me, it’s the cumulative effect of all these mini-paintings-within-the-painting—and their presence within a painting that is also an essay in rectangles and a symphony of gray and green—that tugs between painterly invention and photographic “truth.”

Blair sent me two more paintings in early November, again as JPEGS, and with these notes: “Here are 2 recent paintings I’m pleased with. One is azaleas from a Bahamian window. Our building had to replace our elevator cab this summer. I loved the old one and wanted to remember it.”

Though it’s often hard to tell them apart, Blair’s gouaches and oils divide between paintings made from the slightly exoticizing contexts of travel destinations, and those made at or much closer to home. The Bahamian azaleas and soon-to-be-lost elevator offered one of each. As with that Japanese bathroom window, I fell in love with the painting Blair sent of the elevator cab. Blair likes corners, I think—especially the interior right-angled planes and full stops one encounters in an apartment or hotel hallway, or as here, in the cramped confines of an elevator. Corners set off the juxtaposed planes on which all he does with light plays out. In this one, as he says, we are looking at an elevator cab, although, again, it’s not clear this would be obvious without his information, given that all we see are its walls and a bit of floor. What is obvious is Blair’s delight in the specific sheen and amber hue of the wood-grain formica—a color and a surface for which his fondness is clear in many other paintings of bars and lamps. The handrail is another furnishing detail that Blair uses to great effect as device; in this case, reinforcing the full stop of one wall against another while making a quasi-palindrome of the space through its reflection, and alluding to a vanishing point. Ditto, the simpler black line of the baseboard. Again, though, it’s the way these distinct areas each act as conveyors of light, or its absence, that gets to me: the carefully calibrated degrees of the light’s absorption and reflection on the painted wall and formica; the tiny triangle of metal-studded industrial flooring, neatly framed against its darkening, recessional shadow; the elevator light’s bright poltergeist appearance on the painting’s upper left; an even subtler distinction between that glare and the wall’s pale gleam on the right. That corner of floor also introduces a second vanishing point, or delta, and this vantage, along with the slightly disoriented elevator claustrophobia, save the painting from sentimental homage, suggesting something closer to the mix of familiarity and remove of, say, J. G. Ballard’s descriptions of suburban and corporate surrealist spaces.

In a 1983 interview, conducted around the time he was finishing Empire of the Sun, a work of autobiographical “narrative nonfiction” that represented both a story based on real events and a conscious retreat from his earlier celebration of sci-fi, Ballard observed:

I take for granted that for the imaginative writer, the exercise of the imagination is part of the basic process of coping with reality … The guilty-pleasure notion isn’t to be discounted either, the idea of pursuing an obsession, to a point where it is held together and justified only by aesthetic or notional considerations … A large part of life takes place in that zone, anyway.5

Blair’s recurrent subjects—his cocktails and windows and empty hallways; swimming pools and ashtrays, but also random flowers or half-smoked cigarettes and half-eaten burgers; even his strategic cracks in a window or door—don’t play as obsessions, per se. But beyond their value as painting pretexts, they do carry the charge of guilty pleasures and emotional relief: the pleasure, in Blair’s case, of an innocuous escape.

The subtlety and dispersal of light and the sense of nonsubject made subject—in Blair’s case, a result of his zoom-in on unlikely corners or segments of an actual space—in these two 2020 oils struck me as evidence of a newish shift in emphasis, a move away from declarative subject to a more abstract deployment of spatial effects, to suggest a mood or atmosphere, and the painting of light as presence, rather than as subject or event. This would be in contrast to an earlier painting such as Untitled, 1994, a gouache and pencil on paper that features the dramatic, sharp vertical of a bright white, klieglike light beam, which is shooting up from behind a low, horizontal housing block, painted in kitchen-color pastels. The building sits at middle ground remove, behind a barren dirt-and-scrub field, where Blair situates us as viewers. The low horizontal of the architecture is framed by the hard verticals and horizontals of miscellaneous telephone poles and electric wires. The beam and its vaporous halo—unidentified here by Blair, but familiar to those who know Las Vegas, or its monuments, as the famed Luxor’s, are the action here, even though closer looking reveals Blair’s virtuosic attention to the varied light of a spotlit foreground, and a light-filled window in one of the distant apartments. We are clearly in a back lot, at a remove from that action. What feels different here is that, unlike almost all of Blair’s more recent gouaches and oils of familiar subjects, we feel as if we have seen this scene before, if only in a movie or on TV, or as described, perhaps, in fiction. Though the scene may well have been witnessed by Blair—as it happens, he taught a semester in 1993 at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas—it feels oddly impersonal, probably intentionally so. Curiously, an even earlier gouache on paper, Untitled, 1984, almost identical in size, but horizontal, and inspired by the American Luminist Martin Johnson Heade’s 1859 Approaching Thunder Storm, feels much more intimate and firsthand. Blair’s homage to Heade, a copy made from memory, is painted more traditionally and simply than his later, sci-fi-ish light beam gouache, but it’s oddly more moving and moody: the shifting shades of darkness and picking out of light foreshadow the night sky and ground in his 2020 rental car at Various Small Fires (VSF).

In both of these paintings, the drama and remove of the viewer’s vantage is in marked contrast to many of Blair’s newer still lifes, like the painting in the VSF show, picturing a covered tabletop on a porch, with a small bowl of Cheez-Its and a cigarette lighter, in what looks to be late afternoon light. Full daylight paintings, like this still life, incorporate details that operate almost like sundials, conveying a sense of the precise angle of the sun through the contrast between overall shading and the micro-shadows cast by, in this case, the raised embroidered grid of the table’s cloth covering (Untitled, 2020, in VSF); and the contrast with the brighter light on the foliage in the background, not unlike the sliver of green visible from the Japanese men’s room window. All that experiment and play with actual incandescent and fluorescent light in those earlier ikebana installations; all those big panels of partially painted colored glass or Plexi and light-filled gaps in his later crate sculptures—not to mention a life witnessed “from behind glasses,” to borrow Blair’s suggestion—have made him something of an expert on the varieties of light, direct and mediated. Ironically, years of painting first gouaches and now oils from his camera photographs have also made him an expert in translating plein air photo effects into paint. We don’t need the photo source here to know that Blair was there when the light hit the table—even if he does.

A wildly different Blair painting, also in the VSF show, revisits night light, with some of the drama of the earlier paintings, staged here as a more intriguing meld of everyday encounter and mystery. The 14-by-10½-inch painting is of a rental car “in Scotland” (again, info I have only because Blair said so), black, against a deep black night sky and on a deep mink-gray, gravelly ground. Its elongated, foreign license plate is illuminated in full sci-fi halo, with just enough information in the rounded rear profile of the car and on its circular car logo to reinforce a sense of classy elegance. The perspective, again, is of Blair as witness, but the zoom-in on the license plate pulls us in on the sleuthing. He’s back to the treatment of a concentration of otherworldly light as focal point and event, but now the light glows as if from within the oil, layer on layer, and the blacks are equally complex. The radiating yellow, here, even more than the klieg light beam, feels just a tad alien and reminds me of Walter De Maria’s out-there, hilarious, monochrome conceptual painting, which equated yellow with The Color Men Choose When They Attack the Earth, its title. Blair’s yellow, of course, has a totally plausible source: the license plate lights. Picked out as he has here, and set loose, as it were, in the layers of oil within which the pigment floats, it takes on a life of its own. Blair’s imaginary doesn’t align with any one genre; as with the effects he continually invents, it animates the diurnal experiences he sticks to. Somehow, this manages to be at once anxiety inducing, deeply reassuring, and exhilarating.

Alftan, whose painting is resolutely not based on images captured by the camera, works from an equally exhilarating imaginary, and with similarly unassuming subjects—with a fundamental difference: her paintings are designed to destabilize, to raise questions they can’t answer, to keep us actively engaged in a meticulously planned, profoundly painterly exchange. She is, as I’ve said, adamant in her refusal of photography, choosing instead to contrive a painting from the salient details of an image that “persists” in her memory.6 That most of her paintings draw on images taken from iconic, mostly Western, historical paintings underscores her suggestion that invented images persist more indelibly than others, a Surrealist tenet more readily associated with the writing of fiction, these days, than painting. Alftan’s process entails a compiling of notes on ideas for a given painting, followed by a detailed drawing, which she works from “freehand,” without benefit of projected image or grid. Her idiosyncratic, often oblique or metonymic references may take some time to connect, though, with some help from her titles. (Unlike Blair, Alftan titles her paintings, and the titles play a key part in the project.)

Viewed in reproduction, or at a remove, Alftan’s paintings can feel enlarged, flattened, reduced to essentials along lines that complicate the distinction between painting and illustration and rob the image of any number of the material affects and signifiers she works so hard to build. In print reproduction, her palette reminds of the illustrated pages of a children’s book. This recognition came crashing in on me when I visited Alftan’s first solo Karma show, in fall 2020. After months relegated to online and print, the “live” viewing hit like a wake-up call for senses starved of space and touch. Alftan’s paintings immediately impose a powerful sense of voyeurism—both her relationship to her subject matter, and the role she seems to assign us as viewers, although these roles are not necessarily interchangeable. At the same time, her paintings exude a sense of intimacy, as if letting you in on a secret, or a search. Each of them presents itself like a carefully constructed set of clues, without any clear indication as to what to: a stray frame from a long reel of footage, suggesting much unseen before and after, filled with meticulously marshaled information, as well as a reminder of all that the painting excludes. Because Alftan’s framing, compositional scaling, and color balancing, as well as her attention to subject and title, are each so precisely attended to in her paintings, I thought I had a feel for her work from the monograph alone. I didn’t. With a tour-de-force painting like her Edward Hopper–inspired Morning Sun, 2020, for example, which featured in the Karma show, the opportunity to view the painting up close—and at various removes—is crucial, as is the firsthand experience of its carefully calibrated scale. A complex, polygonal, daggerlike wedge of bright daylight falls across the floor, over furniture, and up the wall of an otherwise unlit room, taking on the contradictory, anthropomorphic presence and jagged contours of a shadow. Alftan’s conflation of shadow and light acts as the destabilizing device here: unlike the Hopper painting whose title she borrows, Alftan does not paint a window to explain the light. The book-lined room in which her sun falls is otherwise darkish. What she does borrow from Hopper, I think, aside from his treatment of light as subject and shape, and his similar degree of voyeuristic remove, is his palette, and a certain density of pigment that seems counterintuitive to the brightness of the light—another effect lost in reproduction. Blair, in a conversation I moderated for their tandem VSF show, picked Morning Sun as one of his favorites. (I’d asked both Alftan and Blair to think about a few of the other’s paintings they especially liked.) “This is a painting you can see from a mile away and it just gets better at every distance.” “On the one hand,” he added, “it’s a kind of an instruction about rendering light on objects. And then it completely flips into a graphic thunderbolt.”

Morning Sun was a standout, but only one of many similarly attention-grabbing paintings in the ingeniously choreographed New York installation. Alftan’s paintings are some of the most haptically orchestrated of any I know. Unlike Blair’s, her painterly effects do not appear to emerge from within layers of paint, or get incised out from within those layers. Alftan’s paint, at least when viewed up close, is fabulously erotic in its range from material blob to corporeally smooth and skinlike; it “sits” on her transparently primed canvases to remind us that it is, indeed, paint. It’s hard to figure out just where the paint morphs into whatever it is she’s painting. Her paintings also read simultaneously as dimensional deposits of pigment and as language. Individual strokes play as phonemes or parts of a corporeal, painterly articulation, in which, as she puts it, “the paint resembles the image as much as the image resembles the paint.” She chooses subjects that allow this—the paint on the hairs of a painted paintbrush, say, in Precision, 2020, in the VSF show. But this undetectable continuum is present, too, in her many paintings of fur, or hair, or grass, or woven wool—or skin, the subject de Kooning famously suggested oil paint “was invented for.” Alftan’s deft moves from thick to thin can feel palpably thrilling. Like Magritte, for whom what was outside the window and on the easel were explicitly interchangeable, Alftan appears to see the world in the same near-far focus she paints, in patterns and textures, and in broad, blurry contours. In the conversation with Blair for the VSF show, she corrected a statement she made in the past, that her paintings are “pictures of the visible,” saying that it’s more accurate to say she paints “pictures of her perception of the visible world.” Alftan’s mind is its own camera. Her inspired differentiation of the density and application of the marks it takes to paint her subjects is such that, in person, and up close, we respond to both haptic and optic subliminally, even before we register the image as image. All this said, Alftan is concerned that her painting not be read as Surrealist. “I only make paintings that are by no means realistic, but that are always a plausible suggestion of the visible world. They’re often strange or even uncanny, but never surreal. Because it’s always about looking. Even though they are constructions.”

Alftan’s paintings of the past few years are painted with a fine brush. In earlier paintings, made with a fatter, rougher brush, the strokes are viscerally evident and can feel almost bawdy, even online. More important, they never quite allow you to forget they’re paint. This makes the continuum, or reversible relationship Alftan seeks between paint and picture, feel weighted in favor of the paint. Consider a painting like Fur II vis-à-vis its earlier, broad-brush antecedent, Fur, both of which, Alftan has said, “point to Dürer,” by which she means Dürer’s indelible, iconic Self-Portrait at Twenty-Eight, from 1500, in which the artist’s mane of long curly locks falls on the fur collar of his coat. In Fur II, which featured in the Karma exhibition, Alftan borrows only the distinctive contour of that collar and the perception of fur. What we see is a contemporary, modish brown coat, cropped just below the collar, hanging on a very un-Dürer wire hanger and a conspicuous black knob. The fur here feels flattish and dense, built from layers of varied browns, in quick and confident narrow strokes. Up close, even in reproduction, you still see the paint as paint, but you feel the weight of the coat as coat. The frisson in Fur II comes around the edges of the fur, where Alftan’s barely there wisps of paint shift the balance entirely to touch. You feel those fur edges as if against your neck. The fact that Alftan has painted the coat on a hanger only intensifies the perception that you could try it on.

In the Karma installation, Fur II hung to the right of Morning Sun and, rather cannily, across from Blue Umbrella, a large Caillebotte-inspired painting dominated by the huge blue umbrella of its title. Its exaggerated scale and full foreground presence invite one set of contrasts regarding perspective and degrees of remove; the play of rain against sun, umbrella vis-à-vis coat, invite another. In Fur, the earlier of Alftan’s Dürer-inspired paintings, the fur in question is a more conspicuously fashionable, overtly feminine fur stole, which lies loosely on the shoulders of an elegant woman—we see only her long pale neck and a bit of chin. The stole is held delicately closed with the forefinger of a similarly pale hand, mimicking Dürer’s famed “point” to himself, in what is widely believed to be the first self-portrait in Western art. The corporeal charge of the wispy paint on the collar of Fur II is “allover” in the earlier Fur, its broad and shiny textured strokes amplified by the sexual charge Alftan builds in by making the subject both fur and female and painting the fur so aggressively. And where, in Fur, Alftan seems keen to emphasize the indexical, pointing finger borrowed from Dürer, in Fur II, decontextualization seems at least as important as the relationship between paint and painted. Neither title nor painting makes any overt reference to the art historical prompt.

The Coat, a terrific 2020 painting in the VSF show, carries further the more controlled haptic affect and degree of decontextualization Alftan builds into Fur II. The painting pictures just the upper left shoulder and upturned collar of a clean-shaven, nondescript male, in an elegantly ribbed wool overcoat. The gestalt image is of a noirish private eye, whom we appear to be watching at safe distance, as we have clearly not attracted his attention. Alftan zooms in, not on his facial features, but on the coat, which she paints with the precision of a tailor, matching the seams perfectly. The impact of the painting comes from Alftan’s balance of deadpan remove with relieflike texture: the broad plane of the shoulder and smooth jaw of the anonymous subject undisturbed by the nibs of painted cloth that Alftan painstakingly extends just over the collar’s edge, while we, the viewer, feel these as if against our own skin. It’s a balance made possible by Alftan’s smaller brush, and by the near-perfect tension she achieves here between haptic and optic, corporeal and semantic, paint and perception.

In Alftan’s Precision, 2020, which Blair also picked as a favorite, these tensions become the painting’s subject. The rhetorical picturing of a brush dipped in paint, just touching an otherwise empty canvas, alludes broadly to the existential subject of the painter’s “blank page.” The more specific allusion here, though, is probably to Velázquez’s Las Meninas, and the similarly poised paintbrush in the artist’s hand, as painted into the painting. Of course, the canvas in Las Meninas is reversed: a painting within the painting that defiantly refuses to reveal its contents, as opposed to a blank canvas, and Velázquez’s brush hovers over his palette. Whether Velázquez is mid-painting, or about to begin, whether his painting within the painting pictures his Las Meninas or something else entirely, are questions that have been debated for years. But based on a suggestion made by Buhe, Alftan’s painting may have been inspired by Michel Foucault’s famous meditation on Las Meninas in The Order of Things, which begins with his observation of Velázquez’s symbolically poised brush: “The skilled hand is suspended in mid-air, arrested in rapt attention on the painter’s gaze; and the gaze, in return, waits upon the arrested gesture. Between the fine point of the brush and the steely gaze, the scene is about to yield up its volume.”7 The gaze in Alftan’s Precision would be both ours and Alftan’s, and we have no better idea here than we do from Las Meninas what her painted brush is about to yield. But Alftan’s ability to empty her homage to the artist’s and philosopher’s question of all but hand and brush—her economy and precision—are precisely what Blair commended in his enthusiastic appreciation of this painting. Curiously, in an earlier conversation, Blair attributed this economy in Alftan’s work, her ability to “leave things out,” to a “Magritte-like talent,” and as something he admired. In that earlier comment, and again in the VSF conversation, he also referred to a painting from Alftan’s New York show, her 2020 Aspirin, in which the artist’s thumb and forefinger grip a neatly scored, circular white pill, rather than a paintbrush. “A hand can be such a simple, effective, iconographic element,” he said. “I’m impressed by Henni’s ability to assert the iconicity of the hand and the circle. I also like that it’s a drug.”

Alftan has said that she’s after “presentness,” not “present tense,” in her painting; she “wants the painting to seduce,” something each of these paintings certainly succeeds in doing. But what to make of her art historical allusions? Alftan often speaks as if the references are obvious, but for those unfamiliar with the history of Western art, her idiosyncratic allusions are easy to miss. The intensely subjective obliqueness with which she engages these references means that they also tend to register subliminally, especially when we can’t name them. While, for many artists, a reference to a known work serves as a kind of coding, Alftan’s paintings don’t summon the “Aha!” recognition of social coding or brand names. To borrow from something Ballard said of his relationship to Surrealism: it’s as if she’s corroborating with what she borrows from her sources. And the recognition they summon plays a key role in our sense of her paintings as clues, or as evidence of unpictured instigations.

Ballard’s vivid descriptive imagery incited a response in me to many of Alftan’s strange juxtapositions, as did his invocation of Odilon Redon’s idea of “making the invisible visible,” and his suggestion that he wasn’t so much influenced by, as “corroborating” with, the Surrealists. I’d been thinking about Ballard with reference to Alftan’s preoccupation with the power of an imaginary, and in trying to identify a surrealism that felt closer to her aesthetic than that of its first-generation painters, as well as an economy of means that her painting shares with his writing. The mood of her paintings, the control over how much information is shared, how much withheld, and the unexpected introduction of a vivid, cooly sexual detail was what brought Ballard’s description to mind, as in a random image from Empire of the Sun, of Jim, the protagonist (based on Ballard), feeding a last bit of food to an American sailor captured by the Japanese and sharing the internment space Jim was also confined to: “He tilted the mess tin and tried to pour a little water into Basie’s mouth, then dipped his fingers in the murky fluid and let Basie suck them.”8 Or, from Super-Cannes, a novel that comes even closer to the domain of Alftan’s subject matter. Ballard’s protagonist is coming home late after a few days away, to what he’s realizing is a marriage ending: “… like those of my friends, in a mess of trivial infidelities and questions with no conceivable answers … as I tiptoed past the darkened lounge, the faint moonlight revealed that she had recruited other company to amuse her. The carpet was marked by almost lunar ridges, left by heel marks that belonged to neither Jane nor myself.”9

A Sudden Gust of Wind II, in the VSF show, is another model of both economy and presence, complicated by art historical allusion. The “II” refers to an earlier painting of that title made by Alftan, and then serves as a further double reference, first to Jeff Wall’s elaborately set up light box photo A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai), 1993, and then to Wall’s reference, in that photo, to the celebrated Hokusai woodblock print, which served as his primary source image. Unlike Alftan, Wall includes Hokusai’s name in his title. In Alftan’s A Sudden Gust of Wind II we’ve zoomed in on a segment of the flurry of papers caught in that gust. The painting is beautifully composed, and looks deceptively simple. It’s a relatively large painting—relative, that is, to Blair’s in this show—measuring 28¾ by 36¼ inches, and pictures just six of the countless papers blowing about in both the Wall and the Hokusai, bluntly painted in bright white against a somewhat generic, shorthand “landscape” of three broad registers of green: grassy green foreground; a deeper shade for some middle ground mountains; and a pale aqua green for the sky. All are painted at the slightly blurry close range of an enlargement, not quite in focus, as if to mimic, or mock, the camera she hasn’t employed, and its notorious failure to register middle ground. For a painting that looks at first glance like “something your kid could do,” Alftan’s virtuosic feats here—simply painting an image that’s convincingly not quite in focus, for starters, then rendering the overscaled papers slightly sharper and not just blowing, but billowed by the wind—are surreptitiously impressive. The perception of cropping and enlarged detail in Alftan’s painting, possibly a nod to Wall’s very different enlarged digital image, again make us anxious for the information the painting excludes. In both the Hokusai print and Wall’s expansive photo reenactment, a spindly tree bends in that same windy gust: Alftan has strategically omitted the person carrying the papers or any specific evidence of the wind. Her earlier A Sudden Gust of Wind, a similarly scaled but vertically formatted painting, sets the flying papers against an office-type table and gridded picture window—notably not open. The black night sky out of that window intensifies the brightness of the white papers. This first Sudden Gust of Wind dates from 2014, and is painted with the same larger brush used in her 2014 Fur Coat. The contrast between the two Sudden Gust paintings raises almost as many questions as does the comparison between Alftan’s 2020 painting, the Wall photo, and the Hokusai, and calls attention to the strictly formal problems Alftan sets for herself, such as the painting of objects in motion, or the effects of wind. It also underscores the idiosyncracy of her allusions to source images. “It’s just the subject that I borrow,” says Alftan, “pieces of paper, blowing around because of a sudden gust of wind,” which the changing settings of the two paintings seems to underscore. But she has also said, “What I thought I could learn from Jeff Wall is his relationship to art history.”

Wall, of course, borrowed a good deal more than a few flying papers from Hokusai. His elaborately staged “real space” reenactment of the Hokusai subject, along with his spectacularized, overscale light box presentation of the digital photo, was part of a career-long effort to interrogate the “reality effects” flaunted by photography, and the expectation that photography belonged to an outside world, while painting remained free to do as it wished. These were questions that rang truer in the nineties, when Wall was still working with light boxes and overtly manipulated digital photography, and before cell phone photography allowed all of us to freely alter our photos and mess with the equation of photograph and evidence. Yet Wall’s questions of photography in the nineties resemble those Magritte had asked earlier in the century of representational painting; and more recently, Wall has acknowledged that “there’s something particularly compelling about forms and shapes that have been caused by fluid flows, whether water or air. The burst of papers in A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai) are flecks of matter caught in such a flow,”10 precisely what Alftan took from Wall.

Neither Alftan, nor Blair, nor I, nor Dugan were able to see the VSF show in situ. But the opportunity the tandem exhibition gave for Alftan and Blair to think concertedly about each other’s work and to share some of those thoughts publicly, albeit online, was an unexpected COVID-19 windfall. I had asked, as I said, that Alftan and Blair select a few works of each other’s that they especially liked for our conversation. Much of what they each focused on first was artist’s shoptalk, formal things. Alftan picked out a 2020 gouache by Blair of a swimming pool, Untitled, 2020—specifically, a swimming pool hit by rain. When I asked her to speak about the painting, her first observation was that it was a gouache on paper, which Blair immediately confirmed. “More dyed than painted,” he said, adding that his wife “took the image, not me.” Alftan spoke to their overlapping interests: “The more I see Dike’s work, the more I see that we have similar subject matter. Drops of rain on water is one that I’ve been desperately trying to do for years, and I always get it wrong … The rendering of water is great; but the reason I wanted to talk about this is the way he painted the curve of the edge of the pool: he didn’t just paint a rectangle. And then, it’s the way he gets the first drops of rain; the first drops of rain are like an event that is just beginning to happen. And I think his rendering is really great here.” I was especially taken by Alftan’s appreciation for Blair’s painting of this real-time interval and event, despite her emphasis on “presentness” in her own painting.

Nothing in the paintings of Alftan or Blair insists that you, the viewer, account for where you are as you look, or what’s going on in your world. In fact, a great deal of the lure each of these artists manages through their paintings hinges on our sustained absorption—the unobtrusive redirection of our attention away from anything outside of it. Yet 2020 was a tough year to look away from—2021, still—much as we are all more than ready to do so. A small gouache painting by Blair of a bedside lamp in a drawing show organized by the Gladstone Gallery, with the punning title 20/20, pointed to something other than plaint or escape, something more in the spirit of the anticipatory presentness Alftan found in Blair’s swimming pool, and that Griffin described at length, in his writing. A vintage lamp, still on, with a mottled rust shade, Blair’s gouache triggered an overwhelming emotional response, not just in me, but also in the friend with whom I saw the show. Its appeal had to do, I think, with Blair’s intuitive predilection for objects and settings that hark back to an earlier moment, and yet, once again, his painting of the light rendered the gouache uncannily present. What tugged at my strings wasn’t the lamp’s period appearance. Sitting unassumingly on a night table, with a space for a pair of glasses not yet set down, and with the light still on, Blair’s gouache was yet another occasion to paint a deeply moving warm glow and something that began to teeter on the edge of symbolic, at least in the context of this year and that show. The quality of time here, as in so many of Blair’s recent gouaches and oils, runs the risk of nostalgia. But the visual, sensory satisfactions of these later paintings owe much more to the simple fact that Blair just gets better and better at what he’s doing, and to the fact that the pleasure he paints so well is never free from anxiety. This postmodern penchant for a “past in the present” has been much theorized, but I prefer Blair’s invocation of a certain synaesthesia he aspires to, maybe even more than the condition of photography.

Toward the end of the VSF conversation, I mentioned this gouache to Blair, as something I’d been disproportionately happy to stumble on. I also mentioned that I’d learned this was his bedside lamp, and that he’d painted a companion gouache, of the very different lamp on his wife’s side of the bed. He nodded backward, in response, from the chair he was sitting on, in his studio. “Those lamps,” he said, “are fifty yards behind me.”

Alftan and Blair, in their very different paintings, render works of patent fiction that are also true things. This wouldn’t interest us if the paintings themselves weren’t so virtuosically weird and wonderful and earnest. Alftan’s destabilized, de- and reconstructed references, like Blair’s still lifes of ventriloquized light, pluck tiny, material truths from the miasma. They make invisible things visible, and leave us to ponder representation itself, and inexplicable joy.

It’s been six months since this essay was first proposed to me, six months in which the world has suffered repeated bouts of the scarily invisible, deadly heaves of COVID-19. Alftan’s finely pointed paintbrush is still poised to begin a painting, and I am more grateful than I can say that Dike Blair has left his bedside light on.