2022

Consulting with Shadows, published by Karma, New York, 2022

JORDAN KANTOR

It’s been a while! Congratulations. It’s been a treat to follow your successes from afar. Thanks for sharing images of your new paintings. I can’t wait to see them in person. It strikes me that your work has really developed since I last visited your studio, when you were still in graduate school. It exudes a new ambition and refinement.

MAJA RUZNIC

Thank you. It hasn’t been easy to keep working since I left school. It’s very competitive; there are so many artists now. But I am married to a painter, and I think that really helps: to be with another artist who is equally ambitious. I think that’s my secret weapon. You probably noticed that the work here is quite different in both color and saturation from the previous body of work (shown at the Harwood Museum). I think this transition can be attributed in part to the fact that something really big happened to me when I gave birth to my daughter. I had postpartum depression that shattered me in every way. It really felt like I was going through some kind of death. I had just finished reading a Sumerian myth about the goddess Inanna and her descent to the Underworld where she confronted Ishtar, her sister and Queen of the Underworld. When I gave birth, it felt like I was living what I had just read about regarding Inanna’s descent. What I mean by that is: the first few months, I really hated being a mom, and I hated how much my body was needed to keep this tiny being alive. But in this struggle, something really great happened to my art. Without consciously asking myself, “What is this work about?,” everything got stripped way down. I came to this strange, almost modernist space of concern for only color and object. So, in some ways, it is a very dangerous place where I am, but it feels right. And I’m a very romantic painter, you know? I’m all about color, all about the surface, all about the brushes. The “story” is not as important as the object. I don’t think I would have gotten there if I didn’t experience so much physical and emotional suffering.

JORDAN KANTOR

Wow. That’s quite a lot to unpack already. I’m sorry! I’m so sorry to hear you had such a hard time.

MAJA RUZNIC

That’s okay! I can laugh about it now!

JORDAN KANTOR

So, there are a couple of implications in what you just shared that might provide a place for us to start. One is to discuss what differentiates this body of work from what came before, on a formal level. We might want to touch on the visual differences in this body of work from previous bodies of work, what you are characterizing as a more “modernist” space. Then, secondly, and perhaps more structurally, would be to discuss how you theorize the role of biography in your work. Indeed, almost everything I’ve read about your work ties interpretation to your personal story. And, in the way that you’re talking about this right now, you’re saying, “The first thing I want to say about my work is what’s going on in my life.” Perhaps it might be useful to dig into that a little bit, if you wish. Not necessarily to rehearse the specifics of your biography, but rather to think about how your lived experience informs the way that you frame the discussion of your work. But perhaps we can start with the first question first. Can you talk about what distinguishes this new body of work formally from what you’ve done before?

MAJA RUZNIC

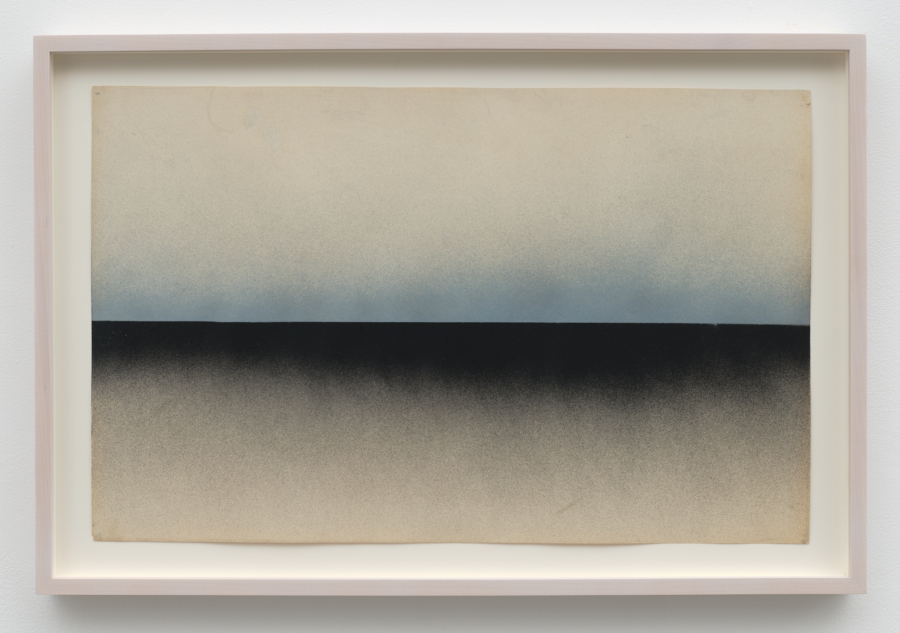

I think the main difference is layering. There are many more layers than there were before. Prior to this body of work, making a kind of haiku-like painting was very important to me: I would start a painting many times before I felt like I was nailing the marks. The painting had to have magic from the very beginning. Because of this, I never experienced the ugly or awkward phase of painting, like a lot of serious painters talk about. Everything had to feel immediate and fresh, almost like an ink drawing. And I think that’s because after graduate school, I worked solely on paper and I worked this way for the next seven years. I didn’t touch oils this whole time because I didn’t have a properly ventilated studio. So, with this new work—something happened very naturally. It was not a conceptual decision to start making work that takes longer, but that’s where I went. I was an insomniac for five months. Postpartum depression and anxiety made it hard to relax and sleep. At night, when I was awake, I’d look out the window and notice the way snow looked in the moonlight and the way the branches of the tree looked like ribs. I somehow found beauty in my inability to sleep. That’s why the work got more layered. I wanted to create a sense of color trapped in darkness. That was my conceptual starting point: What does red look like when it’s cloaked by night? Or purple? These kinds of questions.

JORDAN KANTOR

Something that I admire about your work is how you conjoin the process of making with larger conceptual issues. You’re talking about, right now, a kind of in-betweenness, both formally and conceptually, and how these come together to strengthen each other.

MAJA RUZNIC

That’s the most important thing to my work: to explore the ways in which the “what” and the “how” are braided.

JORDAN KANTOR

That is the kind of thing we were talking about so many years ago.

MAJA RUZNIC

Yes, I remember! You told me that one thing that makes a painting good is not knowing how it was made.

JORDAN KANTOR

Yes, if I recall, I think what we were discussing then was how formalism—really close formal readings—can telescope into something much more philosophical. It’s a way in which you can get to really big arguments through painting’s own material properties and the decisions the artist was making. Maybe we were talking about Luc Tuymans in this respect?

MAJA RUZNIC

Yes, we were! Wow, good memory!

JORDAN KANTOR

[laughs] I think we were talking about how a painting might make space for a larger political reading without explicitly illustrating.

MAJA RUZNIC

I think that’s also why I said earlier that I feel like I’m dipping into this kind of dangerous modernist realm, where I’m starting to work against figuration at times. Recently, whenever a figure appears in my painting, I flip it over, and I start using the arm or the leg as armature—formal shapes that help me develop the painting. More and more, the paintings are becoming color fields and geometric shapes. While I was going through this big personal transformation with insomnia and postpartum depression, I started meditating. I think that a lot of the truth that I arrived at with painting, started to develop with sitting and breathing. I came to understand that you can’t think yourself out of a problem or an emotion. You just have to be with it. And I really see why that kind of presence can make these much bigger implications. When you’re truly present with one thing, a vastness reveals itself. I started using words like “mother,” “father,” “daughter,” and they became containers for colors and shapes. The word became a structure that held it all—that held my intuitive way of painting. The structure of a word gave me a lot of focused freedom while painting.

JORDAN KANTOR

That’s super interesting. Again, you say so much. One thing that I was thinking: I regard your painting practice—at least in the paintings that I’ve seen and in the ways that it has been discussed—as being aligned with expressive traditions. Is this correct?

MAJA RUZNIC

Yeah.

JORDAN KANTOR

And the classical idea of expression in art implies that you, the artist, have something “inside” you, that can be expressed outwardly, which is then received by the viewer. So, there’s a kind of triangulation between what’s inside of you, the language or the objects that you make that putatively “express,” and where it lands with the viewer. When you were talking about insomnia, I thought of this triangulation. Insomnia is a kind of third state between being asleep and awake, a private space between dreams and a conscious world in which you would speak with others using language. That seems like something also related to a space of meditation that you were just describing, too. There’s this idea of what is in an expressive equation of inside me coming out to inside you. There is that middle space that it sounds like is a place where you’re paying attention.

MAJA RUZNIC

You really nailed that third thing! Are you familiar with the artist and philosopher Bracha Ettinger?

JORDAN KANTOR

Only from you.

MAJA RUZNIC

In her writing about the Matrixial Borderspace, she talks about “co-emergence,” which is this idea that the painter and the object activate each other and so, they co-emerge. The painter and the painting being made create a third presence—which is hard to name. I’m really drawn to that because it resonates so much in my body, and I’ve always trusted that. I’ve always trusted that if something feels good on this animal level, it must have purpose. It might not be popular to talk about, but it has some kind of purpose. When I arrive at something that can easily be named, it prevents me from co-emerging, or I feel that it prevents the viewer from co-emerging with the space in the painting, which is where this third thing happens. People have described that third thing happening in nature, or when they’re in a cathedral. It’s like a sixth sense, where your body just recognizes that something about it is special, but you can’t quite know why. So, yes, those nights when I was an insomniac looking at the snow, they felt really private, quiet, and mystical. Actually, I started feeling better when I stopped pitying myself. When I abandoned the pitying, the transformation started. And I think the paintings became more courageous. I allowed them to be more beat up and more unsure of what they are for a really long time. My bandwidth for uncertainty got wider.

JORDAN KANTOR

That sounds really productive.

MAJA RUZNIC

Yeah. It was really productive. I feel lucky that that’s what came out of it. [laughs]

JORDAN KANTOR

Does that create some distance between how you think about your work now and the earlier work?

MAJA RUZNIC

It does, but I don’t know if I have the words for it. All I know is that the work feels more serious. And I’m not even saying that serious work is better than goofy work or funny work. But I think my earlier work had more levity to it. It was lighter. It had an element of … oh, I don’t know! It started becoming really popular, and that’s when I started getting a little twitchy. Like, the woman goddess-y work, you know, with light and mystical things. And then I was like, “Oh no! I see it all around.” It became a trend. Again, it wasn’t a conscious decision to stop that, but I knew that it was not the conversation I wanted to have. I didn’t want it to feel like woman-empowered painting that’s all about celebrating the divine feminine—that felt empty, and not enough. I wanted a deeper and more complex conversation. And somehow, I feel like by just using deeper colors—literally!—and stripping down the celestial feminine goddesses that I was painting to just form and color, was enough to change the tone. And, you know, it’s like every time you shift, you lose an audience, in a way. But I feel like that’s part of who I am as a painter. My work has changed a lot, and it will continue to change. The series that I’m working on right now, I’m calling them rugs: paintings that are like prayer rugs. And it’s really freeing because I told myself, “No figures! You don’t have to put any figures on these prayer rugs.” I’m treating the colors and the compositions and everything within the painting as if they were rugs. And then who knows what will happen after that!

JORDAN KANTOR

Yes. I hear you disidentifying with an interpretive frame that was solidifying around your work, and talking about wanting to make work that’s more serious, but also that’s more wide-ranging, maybe? And that could be more difficult, you said. What is the context that you would most like your work read through? What is that discourse that you want to participate in, or that you already are participating in? Do you think of it that way?

MAJA RUZNIC

That’s a wonderful question. I remember seeing a catalog—it was a long time ago—when Marlene Dumas had installed her paintings at Castello di Rivoli, an old castle which was turned into a contemporary art museum in Italy. The walls there are really old. Everything is sort of disintegrating, and I yearned for something like that: having the work shown in a religious or at least in a spiritual-historical context. I’m not religious; I don’t practice any religion, but the things that I’m reading are opening me up to a kind of religiosity that I sense in myself. In her book This Incredible Need to Believe, Julia Kristeva talks about this human impulse toward religiosity. From what I remember, she talks about how we all have this desire to create meaning and ritual. And I really feel that something about my practice is very religious. So, to answer your question about the context, I’m not sure if white walls in a gallery are the ideal place. Only because I think most people are intimidated to walk into a gallery, you know, like an average person off the street. I think of the paintings that I made for the show as containers of silence. I wanted to make paintings that made one aware of their own breath, their own fragility. Things are really intense right now: with Covid, with global warming, with politics. Maybe things are always crazy, but this is the moment I’m living in, and it feels really chaotic to be alive right now. But the paintings, although dark in color—something people often see as a pejorative—are hopeful, in that, if a person has the patience to stand in front of them for a while, they can create a sense of spaciousness. I think that spaciousness is really what I think we need next, which is to say, we as a people need to listen to each other more rather than proving points. Compassion is spacious. Being right is not. I believe that being open is more difficult than being right. I’ve always made this joke with my husband; I think, if my paintings could be people, they would be more beautiful humans than I am—in the sense that they’re so accepting. They’re equanimous sages, compared to me.

JORDAN KANTOR

That’s interesting. So, you’re talking about an ideal of a painting as something or someone that is accepting, as opposed to someone or something that is speaking? Is that what you mean?

MAJA RUZNIC

Yes, exactly! I don’t want my paintings to teach any lessons or to tell people what’s happening in the world. I don’t want my paintings to mark important events that are happening. Because I think that’s a human drama that repeats, and we think ours is the most important because this is the moment that we’re living in. But I do think that there’s something underneath all of that, and that underneathness, that primordial darkness is what I think we all have in common. Yesterday I listened to this Buddhist poet— Jane Hirschfield—and she talked about how she’s not ready to give up the pronoun “we.” And I thought that was so beautifully problematic and rich. She’s a Zen monk and a writer, an esteemed poet. What she said really resonated. It gave me permission to keep going.

JORDAN KANTOR

Actually, that’s really interesting that you bring up “we,” because I was thinking about the different pronouns in your work and the different subject positions. You use various combinations of “mother,” “father,” “child,” in your titles: I was thinking these titles all indicate relational identities. One is a mother only when you have a child, etc. So, your titling was making me muse on how identity can be mobile and relational. Anyway, in thinking about your work, and what I know about your biography, I was loosely researching the Bosnian War and came across an animation of the changing boundaries during the dissolution of Yugoslavia. The animation is a time lapse in which the different territories become different colors and grow and shrink and become fractured through time. And I was thinking about the politics of naming and how all that naming in those territories was such a contested thing that had real-world, on-the-ground impact for folks there, and especially for you! But I was thinking about the collisions between naming, borders, politics, and changing identities.

MAJA RUZNIC

I get it, yeah!

JORDAN KANTOR

In my free associations, and to dial it in a bit, I was thinking of this through your work and within the frame of Gerhard Richter’s biography and work.

MAJA RUZNIC

Yes!

JORDAN KANTOR

Richter famously moved from East Germany to West Germany around the time the borders closed. This is well rehearsed in the literature on Richter, but my understanding is that he was raised in one political system and in one aesthetic tradition in East Germany, and, after he emigrated to the West, aligns with another tradition. He disavows the work he made before this time, starts his catalogue raisonn. with a new “first” painting, and rewrites his story as if he is beginning as a fully formed thirtysomething in West Germany.

MAJA RUZNIC

Oh, that’s so interesting! I didn’t know that.

JORDAN KANTOR

I find it fascinating how those two identities, the pre-wall and postwall identities, and the different political systems of East Germany and West Germany, can productively be read in the context of the ways in which he shuttles through putatively different modalities in his practice. His work evidences something profound about the mobility, and contingency, of systems of representation, whether those systems are aesthetic or political. It was this train of thought that I was trying to bring to your work and to some of the politics of the name switching in the Bosnian War. Anyway, I’m just freestyling here—but bringing it to your practice, I was thinking about how an identity changes when you become married, when you become a parent, when you decide to be a painter. Those are signal naming changes.

MAJA RUZNIC

I really love what you’re saying, and I didn’t think about it in these terms until now. Before the war (1992–95), my last name was Popovic, which is Serbian and belonged to my biological father. Maja is kind of a … nobody really knows. In former Yugoslavia, you can tell what ethnicity or religion somebody is just by their name. So, my mom gave me a name that was very difficult to locate. Maja is definitely not a Muslim name, and my mom is from a Muslim family, so people often asked me, “Well, what are you? Are you a Serb? Are you a Croat?” I have a mixed background: my biological father is Serbian, and my mother is from a Muslim family, although she is an atheist. I never met my father, due to ethno-religious and god knows what other reasons. I think that’s why I became obsessed with the father figure. Witnessing my husband as a father, witnessing him with Mila—our daughter—made me come to terms with what I never had, and that created its own kind of closure but also desire—desire to feel what Mila feels. I started asking myself questions like, “Who were the fathers in your life?” I was an athlete most of my life; a runner. I ran track at UC Berkeley and my fathers were my coaches.

JORDAN KANTOR

I remember you were a very accomplished runner.

MAJA RUZNIC

I think this obsession with father—with the male figure—made me focused in the studio. I discovered that my father lives in Sweden, and that he is remarried. I also learned that I have another half-sister. I think sometimes when you’re sleep-deprived—which is really common with women who gave birth, your hormones are all over the place—you just start doing weird things. This obsession with looking her up on Facebook, and seeing that she’s also an artist, made me think, “Oh, wow, is that genetically from our father?” The “Father,” “Mother,” “Daughter” labels came only after I made the entire body of work. It was a way to organize. I never have ideas before I start.

JORDAN KANTOR

So, what about your name change?

MAJA RUZNIC

Right. My name changed because my mom remarried. I had to take on his name so that we looked like a neat little family when we entered the US. [laughs] The US Embassy told us that things would be a lot easier if all the family members had the same last name. So, it was out with Popovic (Serbian) and in with Ruznic, a Muslim last name. And then, later, my identity changed again from athlete to artist. I was a serious runner. I wanted to be in the Olympics. All the runningrelated injuries kicked me out of that dream and I found solace in painting. I slowly became an artist. Maybe that’s also why Brendan Dugan—director of Karma—brought up Paul Klee the other day. I showed him images of the current work—these prayer rugs—and he was like, “Something about these reminds me of Paul Klee.” I wasn’t very familiar with Klee, so I looked him up online and I learned that he was really going back and forth between abstraction and figuration. He didn’t seem to care about the differentiation. It was freeing for me to see that. I still struggle when people ask, “Is this an abstract painting or is it a figurative one?” That’s not an interesting question for me at all. I feel a great deal of freedom being able to move in and out of both, because they inform each other. I made a painting that was basically just four triangles—a green, blue, different variations of blue—and I like it hanging next to a portrait. I think of them as a diptych. When you look at the portrait, and in particular, the shape of the forehead, you’ll find the secret math that is also in the abstract piece. I believe that people consume realism quicker than abstract paintings. Perhaps because realistic things are quickly named by our brain. So, we move on. Maybe with an abstract thing you have to stay a little bit longer, to search, to wonder. I want the paintings to talk to each other, and maybe invite the viewer to stay longer with both.

JORDAN KANTOR

So, I think this—let’s call it an exhibition strategy—this strategy of pairing them together works for that purpose. Because, at the very least, you’re saying, “I propose a connection between these two works that are in two different modalities, and if you are here to meet my work where I put it, you will try to recognize that in some sense.” Not that you get a message per se, but just that you issue an invitation to slow down to try to understand what those connections could be. I noticed that in some installation photographs of your work, that you have what I would call a somewhat eccentric installation strategy that you employ with unequal spacing and pairings, which I think is really successful. It leads the viewer to that kind of reading.

MAJA RUZNIC

[laughs] I’m really loving this conversation! It’s really bringing me back to CCA. But better, maybe, even!

JORDAN KANTOR

Such a wide-ranging conversation; there’s so many places to go with this. Let’s go back a bit. So, I had asked you about the context in which you ideally wanted your work discussed. Maybe the better way to say that— because I don’t think that is the artist’s job, necessarily, to talk about their context—but just what kind of contemporary art discourses you are most interested in, and that you feel like you are speaking back to, or conversations you’re speaking into. That’s one question. And you mentioned Marlene Dumas, and maybe that’s a place to start. And then, later, I want to ask you again about Paul Klee, who you mentioned. Okay, let’s start with just the first part of that.

MAJA RUZNIC

Yeah, sure! So, the context. I don’t look to a lot of my contemporaries for kinship. I feel like my work doesn’t have the same sound as a lot of stuff that is popular right now. I’m actually trying to get away from it even more—the sound of today. What I mean by that is, a big conversation in the art world today is identity politics, and something about my more figurative work lends itself more easily to that conversation, and I don’t want that. I live in New Mexico right now, in Placitas, which is really close to Albuquerque. We often take hikes and visit different ruins in our area. We recently visited the Coronado Historic Site and the ruins of Kuaua Pueblo, where some of the wall paintings are preserved. When I saw them, I felt immediately transported. The marks have so much urgency. I feel like I’m talking to those! [laughs] You know? Or Rothko, or Paul Klee, or Louise Bourgeois. I don’t know if what I’m doing is very popular, but luckily, I feel that I have a gallery like Karma that’s really supporting this voice. I’m not really answering that very well, am I?

JORDAN KANTOR

I mean, it’s an open-ended question: this is just an opportunity to articulate the kind of connections that you want to have made with your work. So, if it’s not so much an identity politics connection … I don’t know. There’s a thought experiment that I use when I teach that goes like this: Picture yourself in a really crowded restaurant in New York (back in pre- Covid times of course). It’s Saturday night in Chelsea, maybe, 9:00 p.m., and there are big round tables, and every table has maybe eight people seated around it, engaged in deep conversation and banter. I think of this as a metaphor for the discourses of art: all happening simultaneously, making a din, with discrete conversations going on at different tables. And at each of these tables, you can talk across time to anyone. So, at one table you might find, for example, Picasso talking to Goya.

MAJA RUZNIC

Yeah, that’s great. I would love to be there for that!

JORDAN KANTOR

I would as well! And he’s saying, I don’t know, something about art and politics, or Vel.zquez, or reclining nudes, or whatever he wants to talk to Goya about. Then there’s another table, where an entirely different conversation is happening. The point that I try to illustrate to the students with whom I use this metaphor is that these are already ongoing conversations, happening across time in the discourses of art. So, the pointed question becomes: What do you do when you walk into that restaurant? You listen in on the conversation, and you say, “Oh, I see Picasso is talking to Goya. I would like to sit down.” You ask to pull up a chair, and you sit down, recognizing that you are entering a conversation that has already started. Picasso has already said so much to Goya, but when you join the table, they pause and look at you. They say, “I see that you’ve joined us—what do you have to add?” So, I think that is more where my question goes …

MAJA RUZNIC

That’s a beautiful question, and as you were saying all this, I kept thinking about Vuillard.

JORDAN KANTOR

Okay, great! So, we’re at a table, and one of the people at the table maybe painted something in the Pueblo where you are in New Mexico. And another person at the table is .douard Vuillard.

MAJA RUZNIC

And then we need Louise Bourgeois in there.

JORDAN KANTOR

The party grows! Louise Bourgeois is there. And then you sit down. What is the conversation about? Are you wishing to introduce Louise Bourgeois to the Pueblo painter? Or are you wishing to ask Vuillard technical questions about layering and opacity? What is the conversation that you want to have there?

MAJA RUZNIC

The one thing, when I think about the wall paintings, Louise Bourgeois, Vuillard, Rothko—one thing that all that work has, even though it looks very different on the surface, is that it is undeniably theirs. They’re also dealing with the same thing. I mean, if you look at some of those wall paintings in the kivas, they’re very similar to Louise Bourgeois’s watercolors. They’re all dealing with birth, with rain, with family structures. A lot of these images in the kivas are dealing with—I don’t know to what extent—but they seem to be representing human beings and family structures. There are images of human figures who look like they might be praying to the rain gods for corn to grow. Then there’s Rothko, who is also communing with something like that. It seems like all three of them are dealing with this existential question, and I think I’m just saying to them, “Look, guys, I’m doing it too, but in my own way.” [laughs] It’s like we’re all offering spaciousness. I think that’s why I’m calling the new work prayer rugs—I want them to feel like these things that you hang on the wall that can transport you into another realm—like lifting the veil of illusion in Buddhism. Ram Dass is somebody I’ve been reading and listening to a lot. He talks about the different planes of existence. I feel like all those artists that I really love are peeling back the veil a little bit. Louise Bourgeois is showing us the nastiness of her family structure, and what it has done to her, and how she has created this whole other world based on her childhood memories. I think I’m doing something similar with my work. I’m offering spaces where people can contemplate and think about themselves—not in a cerebral way, but in a bodily way. I want the paintings to make people aware of their own fragility, their own breath. I want them to think of the boots on their feet, and their toes—are they cold? I mean, that’s a lot to expect from a painting, but I’m hoping. When I’m painting, that’s how I judge if it’s good or not, and I only have my own body to tell me, “You’re getting there,” or, “You’re further away.” But there’s something in my body that is very animal, that’s telling me, “Oh, this painting feels really cold, and what does that coldness remind you of?” I’m just hoping to give people opportunities to have those little moments with themselves.

JORDAN KANTOR

So, you’ve talked a lot about context, and what I think about right there is installation strategies. You mentioned Marlene Dumas showing in an old castle, and you mentioned that the white cube may not necessarily be the ideal context for your work, and you mentioned this idea that you’re hoping that the work is an invitation to the viewer to think about their own somatic experience in their own body when they are in front of it. I wonder if you’ve thought about how to engineer the installations that invite more explicitly what you want. I mean, it could be as simple as putting a chair in front of a painting or something. There are ways to manipulate … Or a sofa! And is the sofa dirty, or is the sofa clean, or is the chair hard, or is the chair soft? I mean, there are all kinds of ways to stage-manage the viewer’s experience.

MAJA RUZNIC

You know, I started thinking about it a little bit, but I’m so glad you’re bringing that up, because the show hasn’t happened yet. The main thing that I want is for the lights to be dim. I remember the first time I walked into the Rothko room at the Tate, in London, where all those red paintings are. It’s really dark in there—mainly because the paintings are fading. Something somatic happens when you’re in darkness. You know how your eyes take a moment to adjust when it’s dark out so that you can see? I really love that.

JORDAN KANTOR

Just to switch gears for a moment, I’d like to circle back to your mention of Paul Klee, earlier. When I think of Klee, I recall that image that he made of the angel of history.

MAJA RUZNIC

Yeah, I know which one.

JORDAN KANTOR

The drawing, or rather monotype, that was owned by Walter Benjamin.

MAJA RUZNIC

Oh! I didn’t know that!

JORDAN KANTOR

Yes, and he wrote about it in his “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” There might be a productive triangulation there between your thinking about Klee, and the idea of abstraction, and also a witness to history. All of that goes together with that drawing. Because the angel of history is the one who is getting blown back by destruction.

MAJA RUZNIC

Oh, wow! I don’t know much about Paul Klee at all, and actually, as my Christmas present, I told my husband to get me a Paul Klee book.

JORDAN KANTOR

Here is the text I wanted to share. This is Benjamin: “A Klee painting named ‘Angelus Novus’ shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned towards the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such a violence that the angel can no longer close them.” He’s being blown back. “The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. The storm is what we call progress.”

MAJA RUZNIC

“The storm is what we call progress.” Oh, that’s good! Wow. [laughs] That’s just like, drop the mic right there!

JORDAN KANTOR

Tell me more …

MAJA RUZNIC

Yeah! There’s a part in that quote about attempting to make something whole—can you read that part again?

JORDAN KANTOR

Sure. “The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed.”

MAJA RUZNIC

I’m thinking of a phrase in Jewish teachings—tikkun olam, which, in Hebrew, means to “repair the world” or “make the world whole.” Are you familiar with it?

JORDAN KANTOR

Tell me more.

MAJA RUZNIC

So, from Lurianic Kabbalah teachings, it is believed that before God created the world, the entire universe was filled with a holy presence. God took a breath to draw back and make room for the world. From that first breath, darkness was created. And when God said, “Let there be light,” lightness was created, filling vessels with holy light. God sent those vessels to the world, and if they had each arrived whole, the world would have been perfect. But the holy light was too powerful to be contained, and the vessels split open sending sparks flying everywhere. Some of God’s holy light became trapped inside the shards of the vessels. It is our job to release and gather the sparks. When enough sparks have been gathered, tikkun olam, repair of the world, will be complete. So, the point, or the meaning, of every living being is to bring their own little shard back to the whole. To make the world whole.

JORDAN KANTOR

Oh, yeah. But making the world whole again is a big project!

MAJA RUZNIC

Well, the only way that it can work is if you’re trying to make yourself whole. You can’t control anything other than yourself. I don’t think I’m making the world whole when I’m painting. But I do think something is happening to me, and that because of my practice, I’m a better human. It’s as if I’m rearranging something which then creates some kind of space, mental space, psychic space. I feel really crowded by information and by everything moving so fast—like that angel being blown back. And progress is the—what did it say at the end?—progress is the storm. I don’t really believe in progress. I think new things are happening, but we’re also losing some things when we are “progressing.”

JORDAN KANTOR

I think of this more like an image … You know how in popular movies time is sometimes visualized as a burning strip, like a fuse, that represents an unfolding of time?

MAJA RUZNIC

I do, yeah.

JORDAN KANTOR

I think of this image not so much as progress per se—as in, you’re going somewhere good—but that the angel of history is where the flame is, on the thing that’s moving, looking back.

MAJA RUZNIC

I see. It’s inevitable, in other words.

JORDAN KANTOR

It’s inevitable, but he is moving backward down the fuse, toward the future, but he can only see what has been burned. I don’t know that it’s progress so much as just an unfolding of sequence.

MAJA RUZNIC

That makes me curious. Again, I don’t know too much about Paul Klee’s biography and the timeline of all the work, but I wonder what came first—or maybe it came at the same time, which would be even more interesting in some way. I’m thinking, in particular, of those abstract paintings he did, with little geometric shapes. I wonder if they came before or after this drawing, and if they did, I wonder—

JORDAN KANTOR

I think it’s all around the same time, loosely. This is kind of what I meant about Richter also: there’s these mobile systems of representation, each of which is incomplete and discrete. Writing does what writing does. Geometric stuff does what geometric stuff does. Figurative stuff does what figurative stuff does. Each thing is necessarily partial; they are interchangeable. They all only approximate an experience.

MAJA RUZNIC

Oh, that is so great!

JORDAN KANTOR

I think that may offer a way to get out of an abstract–figurative dyad that you were saying frustrates you.

MAJA RUZNIC

That’s it. I’m going to borrow that model, if that’s okay. [laughs]

JORDAN KANTOR

I didn’t invent it! [laughs]

MAJA RUZNIC

No, but I love what you said about how each mode is incomplete.

JORDAN KANTOR

Yes. Well, because it’s only in its own system, an invitation to diversity— the opposite of claiming absolute truth.

MAJA RUZNIC

Exactly. And I think it’s also a way of resisting a stable identity.

JORDAN KANTOR

There you go. See, so that’s maybe where I came around to the names. The names of the countries, the names of the political systems, the names of the people, all of that. That’s related.

MAJA RUZNIC

I have a memory I’d like to share, which is maybe unrelated, but somehow in my mind it seems related to this idea of resisting a stable identity. When I was little, before the war, my grandma sent me to a Muslim version of Sunday school, and I really hated it. It just didn’t feel right. One thing we all had to do in the beginning was to stand up and say our name. And this was my first micro-trauma. I remember standing up and saying, “Hi, my name is Maja Popovic.” Popovic is a Serbian Orthodox last name. And I remember all the kids kind of looking back and gasping, like, “How dare you, that’s so sacrilegious that someone with your name comes into this sort of holy place.” I don’t know, it’s somehow connected to this. I remember feeling like my name was dirty, that the label was not right. And I feel like that is present everywhere, you know, the right label: “vaxxer” or “anti-vaxxer,” “left” or “right.” It’s kind of how we decide who is in our tribe. People are actually really proud about naming their tribe. Like, “These are my folks.” And I find that very dangerous. Maybe it’s because I came from a place where this sort of pride and naming led to a civil war.

JORDAN KANTOR

You speak from first-person experience.

MAJA RUZNIC

We covered so much!

JORDAN KANTOR

I think that we could talk for a long time, too, though.