March 2021

Animals Birds Flowers Moons, published by Karma, New York, 2021

I have a Bird in spring Which for myself doth sing — The spring decoys.

And as the summer nears — And as the Rose appears, Robin is gone.

Yet do I not repine Knowing that Bird of mine Though flown —

Learneth beyond the sea Melody new for me

And will return.

Fast in safer hand

Held in a truer Land

Are mine —

And though they now depart,

Tell I my doubting heart They’re thine.

In a serener Bright,

In a more golden light

I see

Each little doubt and fear, Each little discord here Removed.

Then will I not repine, Knowing that Bird of mine Though flown

Shall in distant tree Bright melody for me Return.

—Emily Dickinson

I hear a cardinal sing this morn The sun is shining, too Harbingers of glorious gifts Labeled from God to You

—Sister Rose M. Feess, one of the “8 Nuns who died from Covid” during the same 2 weeks, including 4 on the same day, from Notre Dame of Elm Grove, a Wisconsin retirement home for Roman Catholic nuns, reported Dec. 18, 2020 in the New York Times

“Art has always been side by side with religion. It’s been in the religious arena forever.”

—Ann Craven, 20111

I live with a wonderful Ann Craven diptych, Bold as Love. In it, a yellow-bellied blue bird, perhaps a canary, looks up to the sky. Behind it is a psychedelic whirlwind that Jimi Hendrix would approve of, swirling away—but the bird seems to have no knowledge of this. The second painting is almost the same: there are slight differences, like one of those “Spot the Differences” cartoons in the Highlights Magazine I read as a child. We don’t have enough room for both paintings on the same floor, but one is in my studio, which is also the habitat of our real life rescued parrots, Matisse, a Catalina Macaw, serendipitously almost the same colors as Ann’s painting, and Picasso, our African Grey. Ann’s painting strengthens the aesthetic feng-shui of my studio world, and I could swear that the birds are edified by it, too—maybe they see themselves in it like I do. We are altogether a part of Ann’s flock. The other painting resides behind my husband and I upstairs, in our main living area, where it holds court amidst other coveted works. This painting is the queen of that flock, literally watching over us: I find my eyes often drawn to it more than anything moving on TV. If there was ever a fire, god forbid, I would grab Ann’s paintings first, after my husband and my pets, because her work so enlightens our world.

My first New York City artworld opening dinner was at Ann’s infamous 14th Street loft, years ago. Andrew and I had just moved to the city so that he could attend graduate school at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center. While at an earlier dinner hosted by a family friend, the then art editor for the New Yorker invited us to accompany him to Ann’s opening and dinner. He had just put one of Ann’s glorious moons in the magazine’s listings section. I believe it was for her first solo exhibition at Lauren Wittels gallery, way back in 1995. The dinner itself was warm and raucous. I didn’t know many there, but Ann made us feel like welcome guests. We ladled spaghetti onto our plates and felt like we were finally hobnobbing with the best of the NYC artworld. I was blown away by her moons—hung salon-style, covering the walls, each one painted on a separate day for what seemed to be a year. They were individual but unique; a sublime aesthetic record of gazing at the moon—always the same but ever-changing, capturing the moment that most people forget, but here forever frozen in time.

That loft sadly and monumentally burned one tragic night in a huge fire—all of Ann’s fantastic artworks went up in flames. A friend of mine once said that if our art is lost or stolen, we can always make it again. I don’t think that this is Ann’s project, but I always wonder—having survived this and other tragic losses—if making something again and again helps to compensate for loss. To have many copies of the same thing helps ensure that they will be there forever, no matter what.

My Catalina Macaw is a product of humankind: Catalinas don’t exist in nature; they are a hybrid with traits derived from the breeding of the blue and gold and scarlet macaw species, and don’t have a true scientific name. But this doesn’t mean that our Macaw Matisse doesn’t have agency, or a personality—he is a cranky old man (perhaps like his namesake?) who is beautiful, but bites. He cries out for attention and gets it. He is a lovable grouch who appreciates what we feed him with exclaims of “MMMMH!” When we greet him, he says, “Hello.” Matisse genuinely feels like a smart, precocious toddler with a sharp pair of scissors: his beak. Like my two parrots, my two Ann paintings—of the same image with the background inverted—are like twins: they may look alike, but are never exactly the same.

Ann is a big Agnes Martin fan. Martin once said, “We have a tremendous range of abstract feelings, but we don’t pay attention to them.”2 Arne Glimcher, the famous dealer, and a great friend of Martin, quotes her as saying: “From music people accept pure emotion, but from art they demand explanation. These paintings are pure emotion. They are paintings of states of existence, innocence, happiness, the sublime.”3 Glimcher tells a story of Martin and his eleven-year old granddaughter:

My granddaughter was … in Agnes’s apartment, and there was a rose in a vase. She was mesmerized by the rose, and Agnes saw that. She picked up the rose and said, “Is this rose beautiful, Isabel?” and Isabel said, “Yes, this rose is beautiful.” Then Martin put the rose behind her back, and she said to Isabel, “Is the rose still beautiful?” and Isabel said “Yes, the rose is still beautiful.” And she said, “You see the beauty is not in the rose, the beauty is in your mind.”4

Ann’s paintings don’t aesthetically resemble Agnes Martin’s, but in a post-postmodern way, perhaps, they are conceptually similar. They are, by way of Barthes, in their “third meaning,” beyond the symbolic. For me, postmodernism looks at the aesthetic language of modernism and takes a step back, seeing how a work of art might not have a singular truth or “universal value,” as in modernism. A work of art operates in a critical dis-course as language within a larger culture. There isn’t one truth: rather, there is a multiplicity of truths that allows for a work of art to simultaneously exist within ideology and be critical of the culture in which it is produced. The post-postmodernity of Ann’s art is the “have your cake and it eat too” plan, where art can critically participate and recognize itself as a language beyond the hegemony of the picture plane—but also leave room for transcendence, beauty, emotions, and feelings, the ineffable and the sublime.

Ann’s paintings aren’t merely about their subject matter of moons, birds, deer, horses, squirrels, lobsters, and flowers—they are only these by description and genre. Munch’s The Scream (1893) isn’t about the Home Alone guy making his iconic gesture, it’s about how the totality of all its forms—the swirls in the sky, the bridge, and the onlookers—evokes a synaesthetic surround of the sound and feeling of a scream. Ann’s paintings are like this: they are, importantly, not about pain, but about beauty, feelings, transcendence. They are the totality of all the figural and scenic forms together, evoking the indescribable.

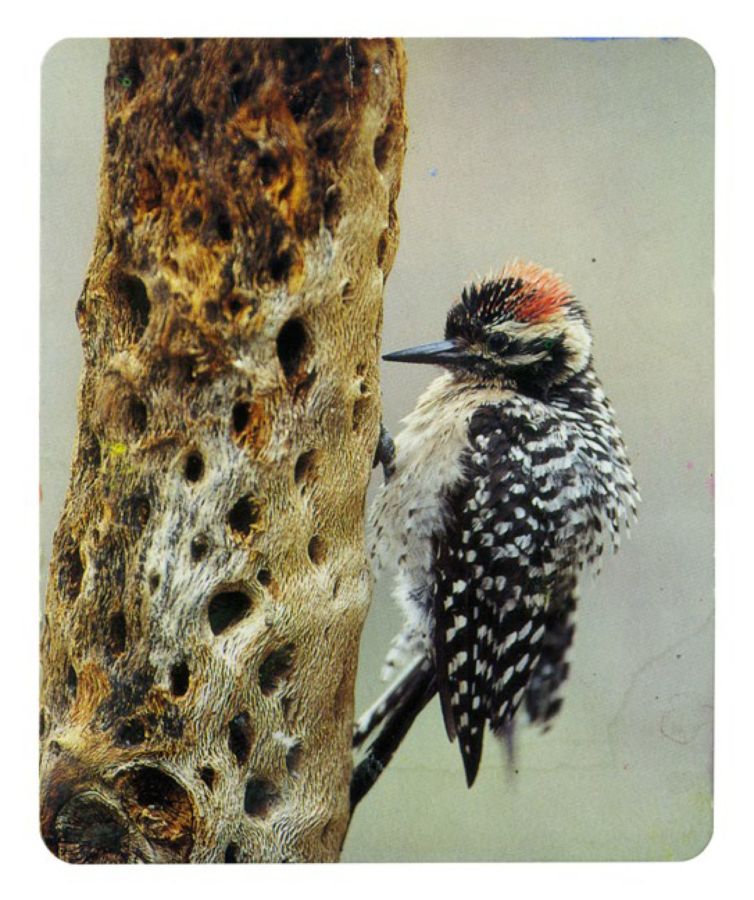

Ann’s birds come from bird catalogs, the bathetic kind you might see in the back of a pet store. Her deer are derived in part from the 1973 dystopian film Soylent Green, where the paternal grandfather figure, played by Edward G. Robinson, agrees to sacrifice himself to suicide—therefore making more Soylent Green food to supply to their overcrowded world—and is rewarded by a series of color films of deer in nature projected across a large screen during his dying moments. Ann’s current work might also be quoting artistic greats like fellow Maine denizen Marsden Hartley’s lobsters on black backgrounds; or the modern Picabia cardinals; or the genius and iconic naturalist, Audubon, who shot and stuffed his beautiful snowy owls in order to save them. But Ann takes all these references to a different level—their signifiers are removed from the signified, and brought into a new semiotic realm, to quote Roland Barthes’s “The Third Meaning,” in reference to the transcendent quality of Eisenstein film stills: “The obtuse meaning is a signifier without a signified, hence the difficulty in naming it.”5

I’ve now lived in two houses with Ann’s birds. And like the moon, they haven’t changed. But in subtle, and not-so-subtle ways, I’ve changed, and so have my feelings toward the works. They are like old friends—or beloved pets—that have matured as they’ve been integrated into our family. They are also like mirrors: I’m constantly reminded that it is my own projection that animates these images. It is what the paintings strategically, through Ann’s genius, conjure within my unconscious that drives my ever-changing reac-tions. When admiring her works, I’m conscious of my consciousness, objectifying myself as I look upon them, making me feel more alive. It gives me the same vitalizing impression as gazing at a real moon, flower, bird, squirrel, or owl. But like those things, each of Ann’s paintings are unique—they are sensitive, emotive, painterly. I can feel something in the interaction of the elements of the works, the palate, and the brushstrokes that come together in a living, aesthetic machine of a painting that is powerful, beyond its subject matter. These paintings are like little Gods, in that the frame of the canvas has within it a whole world that it looks after. And like the rose in The Little Prince, each one feels like it is the only one in the world, when in fact it is one of many: “It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.”6

I’m not religious, but I am spiritual, and Buddhism makes a lot of sense to me. A Buddhist might ask: what is the self? Is it your mind? Is it your body? Is it neither of those things or both? If you hit your thumb with a hammer, you might exclaim, “I can’t believe I did that!” Who is the “I” you are talking about? Michelangelo wanted to put his soul into everything he did: not in a Faustian “Devil and Daniel Webster” way, but to give life to his works. What ultimately gives Ann’s paintings such beauty—despite the fact that they may be copies, or duplicates—is that they diverge from one another: they are each unique beyond the source image itself. In her own cool way, if Agnes Martin didn’t like how a color puddled, or how a brushstroke stuck out, she would then destroy the painting. In part what I love about Ann’s work is how each image contains so much reflecting upon the work, and reflecting upon what it might mean for her at that point in time. How the two images differ, both from the original source and from the painting that they may be quoting, is also what is “her” about them. How these differences index a feeling or a moment in time is what gives them their soul, their life, their beingness. That’s what I treasure about them. Ann’s work is conceptual, and processual, but each individual piece has a life and a soul of its own.

There is an everyday sublime to Ann’s works. They capture the little moments when we feel something grander than us: hearing a cardinal singing, or glancing at a newly bloomed flower, or admiring the beauty of the moon before going to bed. Ann interrupts the narrative flow of life by reacquainting us with those feelings, those projections, as we gaze upon these things—things that, in and of themselves, are ordinary. But like Martin’s rose, their beauty is in our minds. The figures in Ann’s works become avatars to project ourselves onto. We become the birds or the moons. We are conscious that we are just one among many, in this dying nature of melancholy, of global warming, of political strife, of aging itself. We need one another, and we need the love depicted in Ann’s work to survive.

1. Ann Craven excerpts from my interview with the artist, when I curated her into the “8 Americans” exhibition at he Muruani & Noirhomme gallery in Brussels in 2011

2. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=902YXjchQsk&feature=youtu.be

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Barthes, The Third Meaning in Image, Music Text, Hill and Wang, 1977, pg. 61.

6. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince.