LOZANO C. 1962, Karma, New York, 2016.

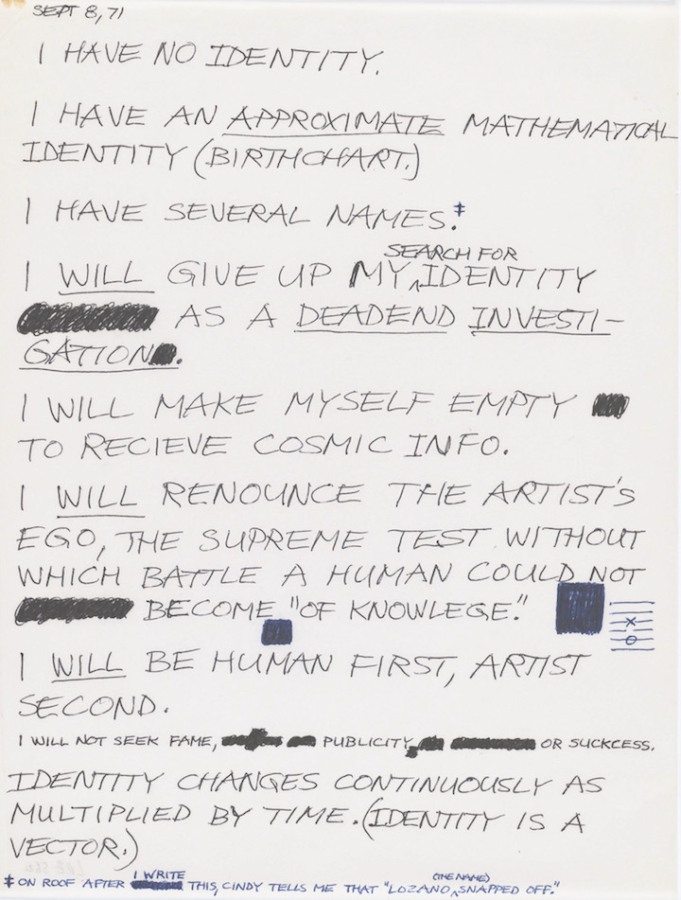

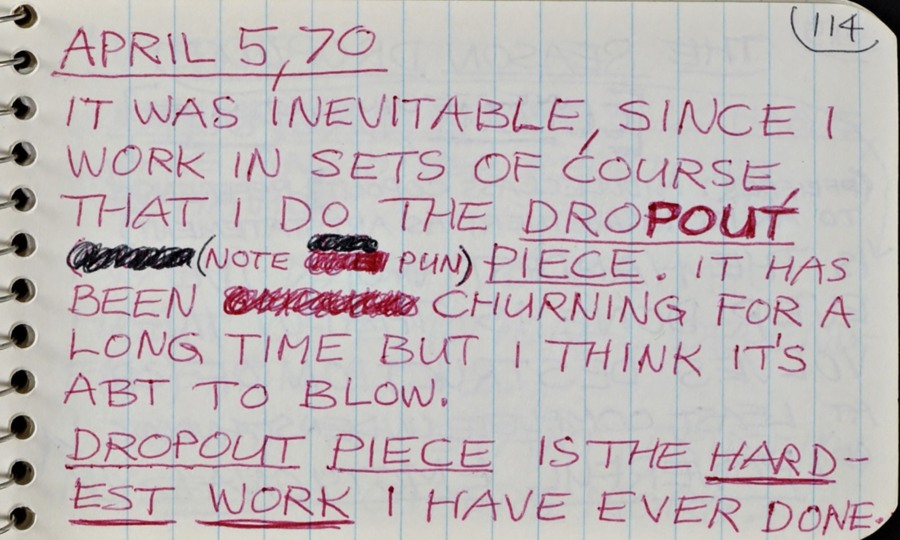

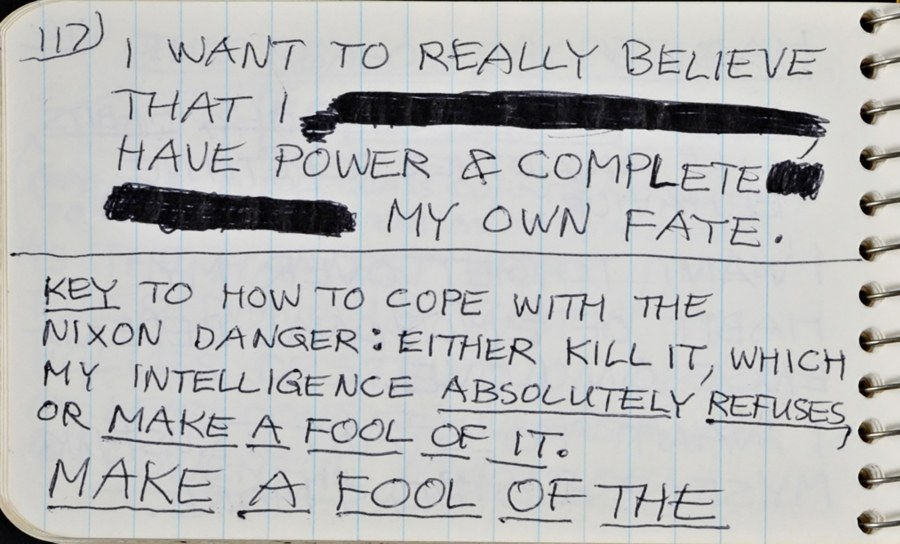

By 1962, the ’50s were coming to an end, and for many artists there would be no looking back. Lee Lozano was one of them, and one who we remember, most likely because she set about forgetting us, whoever we are—the art world, so-called, its participants and those on the outside looking in, who get inside and eventually want out, disillusioned or destined to be, as well as careerists and conspirators, those for whom art is merely a means to an end, rather than a higher pursuit, an endless end in itself. Lozano departed while still very much among the living, flipping a cerebral bird to the New York gallery world in 1971 never to return, an absence that extended for twenty-eight years, until her death in 1999. Her departure, it’s important to note, was not precipitated by the usual frustrations and disappointments that may occasion an artist to stop, or give up, having been offered less and less or nothing at all, but because she wanted something more of herself: to be the primary, driving force of her own destiny, no longer reliant on others for approval, love, and direction. (Being told what to do, filling orders and fulfilling expectations should never count towards being “represented.”) As Lozano clearly stated in a notebook entry dated April 5, 1970: “I WANT TO REALLY BELIEVE THAT I HAVE POWER & COMPLETE MY OWN FATE.” In these same notes she refers to Dropout Piece, her final, ongoing work, for which she would later, and posthumously, become famous, a work that, in its nearly three decades, shows up the durational performances of recent times to be just what they are, a matter of entertainment that manages simultaneously to impress and fall far short. In stark contrast to life-engagement of the sort Lozano was willing to explore—going beyond the safe and circumscribed limits of the art “world”—a day-long spectacle appears trivial, a mediocre diversion interchangeable with so many others, boring, like the drill Lozano drew in 1963. Moreover, artists rediscovered after being absent from the scene for a protracted period are usually willing and eager to return, availing themselves of attention and reward, but not Lozano, as is true for her nearest descendant in withdrawal, Cady Noland. Lozano was hardcore. To come back would have immediately and totally negated Dropout Piece, a work that tends to be misunderstood as negative, as a rejection, when it is not. To have the power of determining her fate, this is something Lozano needed and actively sought, and pursued from the very start.

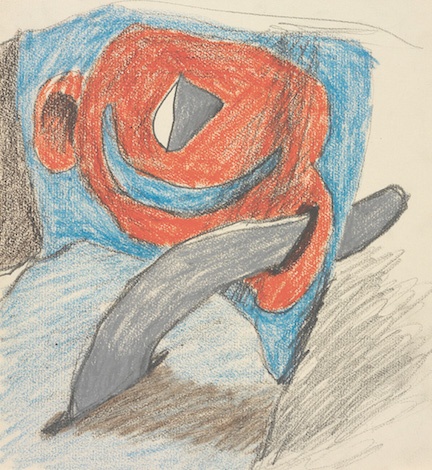

No title, ca. 1962, graphite and colored pencil on paper, 9³⁄8 × 8½ inches

We tend to forget that art is not just the painting, the drawing, the photo, the film or the sculpture before us, something in two or three dimensions, something framed or tacked to a wall, illuminating a screen and looping endlessly, bought and sold. It is a manifestation of the artist, of a life, and when that person embodies their work with the full force of his or her personality, and, as is the case with Lozano, her extremity, we are compelled to consider that it both records and is a means to measure how artists see themselves, shift directions, reinvent and sometimes get rid of them-selves. Body-operating always has its psychosexual side, its political dimension. Lozano left behind more than a body of work, one comprised in fact of multiple bodies, parallel and divergent; her body and mind remain, imprinted on everything she did, inscribed on every page, a core of energy unleashed along various vectors, identity, as she proclaimed, being but one of them. Lozano left behind a corpus, articulated by a voice that is at times prescient, angry, wistful, mocking, inspired, and confounding. She offers any number of entry points, the most vocalized of her thoughts to be found in the captions of drawings, in the messages of text pieces, and of course in her notebooks, filled with enough ideas to keep any number of artists busy for a long time to come. But these notes don’t begin until later on, in what some may identify as her brief career. (If we look only at her time exhibiting and living primarily in New York, it’s about a dozen years; if we include Dropout Piece, and we should, it’s almost forty.) And so there is no published writing by the artist dealing with the period in question, nor with the works produced in the very early ’60s, paintings and drawings that are not easily integrated within what came after; yet this is an artist who compels us to ask: How do we reconcile an art that has little or no patience for reconciliation? Tune In, Turn On, Drop Out.

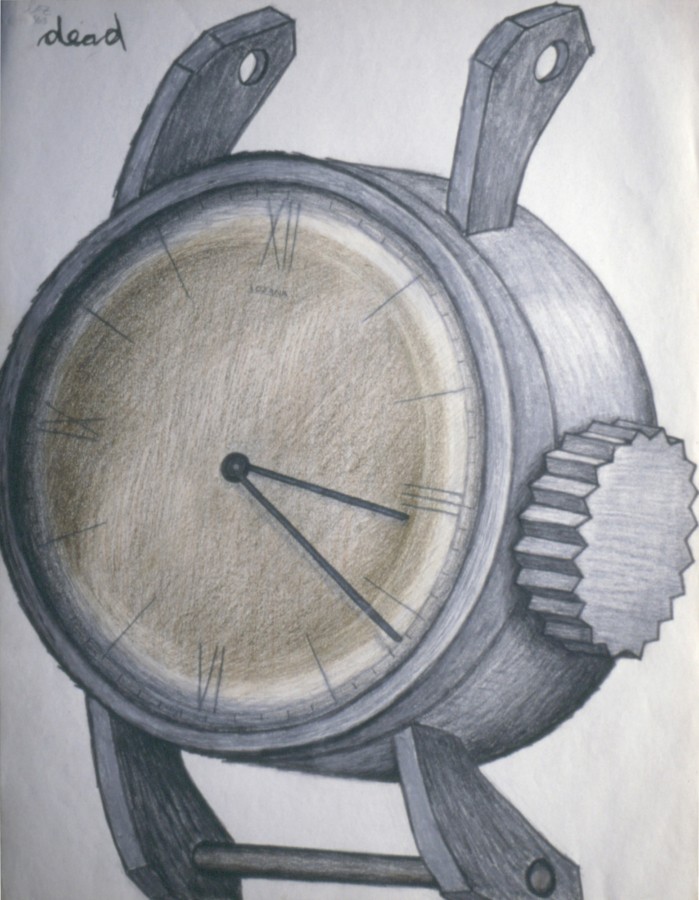

No title, 1963, graphite and crayon on paper, 29 × 23 inches

We see the ’50s that Lozano left behind as equally personal, her prior life and identity, and collective—even standing apart in her need to connect (Dialogue Piece, 1969)—sharing a passage with other artists from that decade into the headier ’60s. In a neatly printed biography written up by Lozano in 1970, only a year before leaving New York and bringing her life as an exhibiting/producing artist to an end, she reflects objectively on her past, and with more than temporal distance. Her “only true name” is given as her date, time, and place of birth: Nov. 5, 1930, 4:25 PM, Newark, N.J. Her first “change of name” is noted as occurring three days after, an obvious reference to her parents having chosen a name, when she becomes Lenore Knaster. The second change is in 1944, at the age of fourteen, when she insists on being called by the masculine-sounding Lee—as a “rejection of traditional American middle-class female trip”—and the third, when she marries in 1956, and is legally known as Lee Lozano. (There would ultimately be a fourth, after leaving New York for Dallas, where she wanted to be called E.) Her education is listed: at the University of Chicago, 1948–51, B.A. and at the Art Institute of Chicago, 1956–60, B.F.A., followed by travel in Europe, 1960–61. She notes psychoanalysis, 1957–59; abortion, 1955; marriage, 1956–60; and perhaps most interestingly, sex, 1931 continuing; drugs, 1959 continuing; art, 1935 continuing; and science, 1940 continuing. Thus, her interest in science began when she was ten, her engagement with art from the age of five, her use of drugs as she neared thirty, and sex from the age of one! In this retrospective admission of having always been a sexual creature, Lozano’s passage from the ’50s to the ’60s, as for so many others of her generation, is not without a heightened awareness of just how far she had come, of who she was, was no longer, and, by her own account, perhaps had always been.

No title, 1971, pen on vellum, 11 × 8½ inches

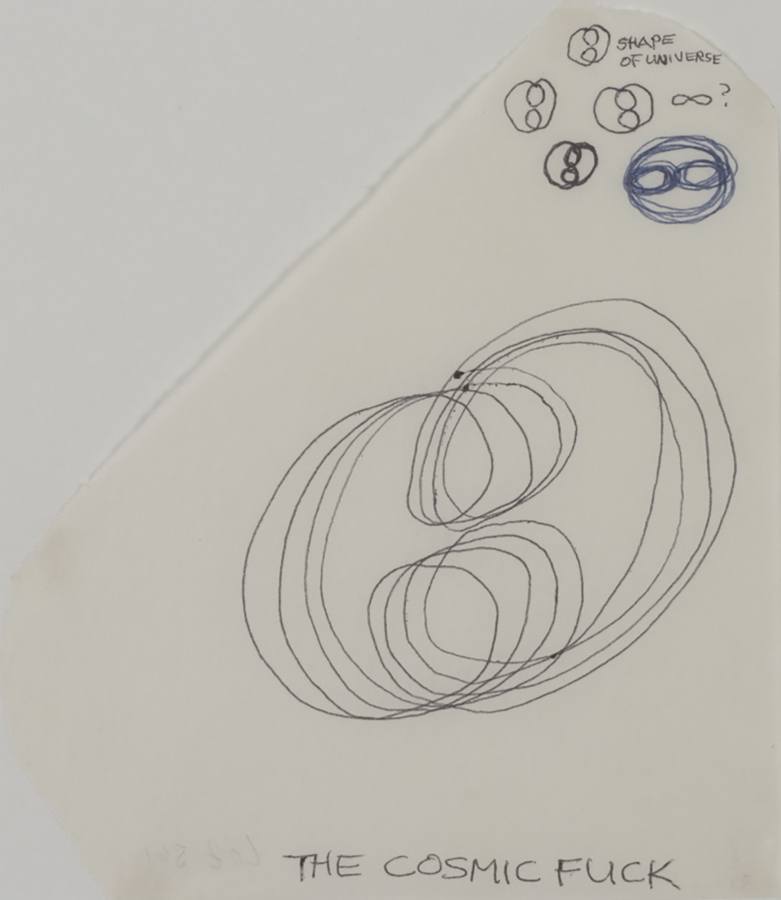

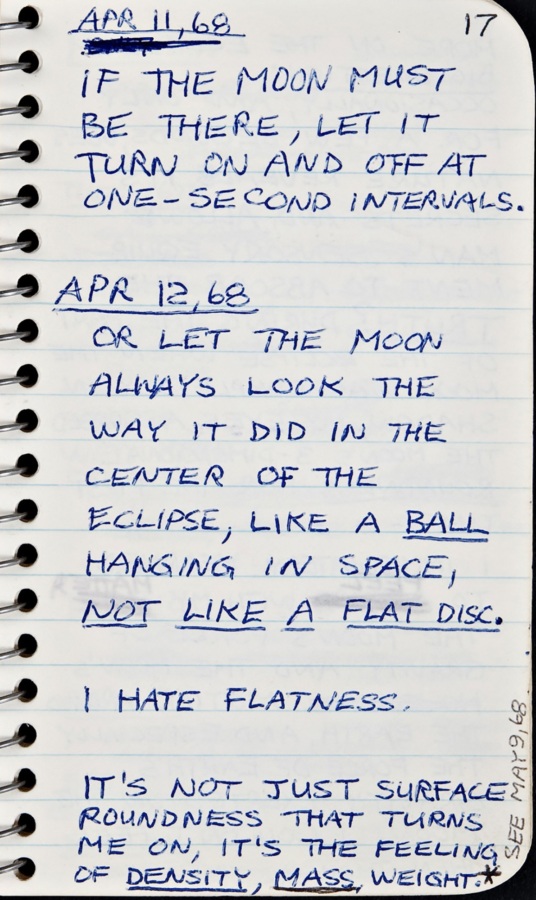

Psychoanalysis, the rejection of marriage and motherhood, traditional femininity, tightly scripted roles and behavior, an upending of what had come before, all this can be seen in the paintings and drawings she created in the early ’60s: all display an unbridled will to misfit. Although there may be no notebooks from that time, and these works involve no captions or text, they serve to represent her mind and voice as she transformed herself, propelled herself towards the artist, the force of nature, she would come to be in the latter years of that tumultuous decade. In the works circa ’62 and onward, she is the anarchic conductor of energies that disrupt all sorts of spatial/representational levels of perception. Imagine a fluid intermingling of Abstract Expressionism in terms of a figurative disfiguration (after de Kooning), Pop comic rendering (pre-Guston), a heady Surrealism that anticipates the mind-expan-sion of the Wave Paintings (by way of peyote and LSD, “I put acid into these paintings, metaphorically”), and a cubism that is circular rather than faceted by geometry. Lozano’s “cubism” is formed by sloping sides and angles that curve like a flexible body and mind wrapping itself around another body, coiled around an idea, poking and probing, a penetration of space that is supple and sexual, what she called “the cosmic fuck.” As she went on to assert in ’68, years after moving on from these early works, yet allowing us to glimpse the energies and sensibility that wrestled them into being, and would continue to animate and dominate her thinking: “It’s not just surface roundness that turns me on, it’s the feeling of density, mass, weight.” Lozano, if there was ever any doubt, was always on top.

No title, n. d., pen on vellum, 6½ × 5¾ inches

These early works will be a surprise for those who came to Lozano through the Wave series and her conceptual/cerebral/ performative propositions, and even the Tool paintings, which precede and to some extent inform them. The early ’60s paintings, while intimate in format, are densely packed with information. A few of these small paintings have a wide horizontal format, frieze-like despite their small scale. Within a few short years, Lozano would go on to create large, at times multi-part paintings that would appear to occupy or physically traverse the space of the room, but in the early ’60s she seems to have been working at a table or desk, in close proximity to her surface, giving an immediacy to the faster irreverent images, and a stillness to the spookier scenes. These works have been painted with a brushiness that has been built up, in some cases as if it was modeling paste, but then Lozano saw paint as “matter in solid state”—as opposed to Pollock, for whom she also identified it as matter, albeit in “liquid state,” and quite possibly even after it had dried. Her palette of chocolate and cocoa browns, ashen smudged blacks, steel grays, and dirty whites is offset by orange and red (how else to represent drops of blood and one possessed?) and on occasion, quite strikingly, a deep yet bright blue ground. The paintings are all framed, many with simple, thin strips of wood (from behind, the staples at each corner appear almost surgical, crudely so), a reminder that these works have now passed the half-century mark, the frame containing the image or tableau. In one painting, however, an elongated penis rises up from the bottom of the picture to penetrate a vertical form that occupies the right side, the tip of its head painted on the frame—its excitement or aggression defying the picture plane. In others, this “penis” emerges from the center of a face as an eroticized, exaggerated Pinocchio nose—man as pathological liar? Or simply boastful—extends from an eye and is poised between two fingers like a fat cigar, and is rendered serpentine, snakily invading a sculptural stage set. The appearance of a phallic form over an obliterated face resembles a baseball bat in one painting (with three crosses planted on top of the head, as if it was a graveyard, a Gothic “Boot Hill”) as a toothy blob bites its cheek, and a long, wide stake in another. Here, the solid bar-like object collides with a fiery, demonic face, a sharp pair of fangs identify-ing this creature as vampiric.

Private Book 1, 1968, p. 17

The mood in these works shifts from playful to somber, from humorous to agitated, with quiet and noise, sometimes in the very same painting. The palpable emotion in some is oddly affecting—as with one in which a doll-like body slumps forward to bury its head in an open box (the “bad painting” of Neil Jenney meets the forlorn castaways of Mike Kelley), or when a melancholic figure is caught, almost photo-graphically cropped around mid-face, possibly as something lifeless dangles from its mouth. These are to be counted among Lozano’s stranger images—would we ever have seen them as hers before?—and up against the pure perversity of her anarchic picture-making, their poignancy is even more resonant. Only now are they recognizably Lozano’s. While it’s difficult to imagine what anyone would have made of these works in the early ’60s—that is if they had been exhibited at the time, or written about, given context—we have to admit: Is getting our heads around them any easier today? But then Lee Lozano never made anything easy for us or for her-self. She continues to cause trouble, to alternately repel us and draw us deep inside, to amaze and confound us, and she always will. More than anything, this suggests that Lozano, in an end permanently deferred, as if there was any other recourse, determined her fateful fate after all.

Private Book 8, 1970, pp. 114, 117

Published on the occasion

of the exhibition at

Karma

188 East 2nd Street

New York, NY 10009

Edition of 1,000