LOZANO C. 1962, Karma, New York, 2016.

This is a story about a woman who rejected two different communities. A successful New York-based artist in the 1960s, by the early 1970s Lee Lozano (1930–1999) was a woman who stopped speaking to women and an artist who had abandoned the New York art world. Largely forgotten by art history, Lozano is now experiencing something of a small renaissance. Yet the new art world attention shies from her rigorous abandonment of both it and the world of women, wanting instead to valorize her paintings, and to commend the prescient nature of her conceptual pieces. But I remain curious, fascinated even, by the extreme nature of her rejection, and before merely repatriating her want to think through why it is that the refusal of women feels consummately pathological and the rejection of the New York art world residually idealistic.

Lozano went to New York as a painter in the early 1960s. Her first major body of paintings was a rough-and-tumble mixture of cocks and cunts that morph together, mix ineluctably with, and transform into a variety of tools—screwdrivers, bolts, and hammers. The paint is thick, creamy, and sexy, and the overall images are arresting, as if the cartoon style of Philip Guston had somehow encountered contemporary cyborg fantasies of a complete merger of body and machine. The sexuality imaged in these paintings and drawings, all done in the early 1960s, is hardly the soft-core liberation offered by the then recently founded Playboy. It lends itself more to accounts of sexuality that stem from Freud’s theory of the polymorphous sexuality of children or Bataille’s Story of the Eye, which evokes a body that experiences a kind of perpetual slippage of meaning and signification—tits become balls, and balls become eyes, and eyes are like cunts, and so on. A polymorphously perverse account of sexuality lends itself to a feminist analysis, as it refuses to render the body and its sexuality hierarchical and implies instead a decentered experience of the body less dependent upon vision, voyeurism, spectacle, and objectification. Lozano’s evocation of this body is raucous, muscular, and simultaneously disturbing and deeply erotic (not that those two attributes are always different).

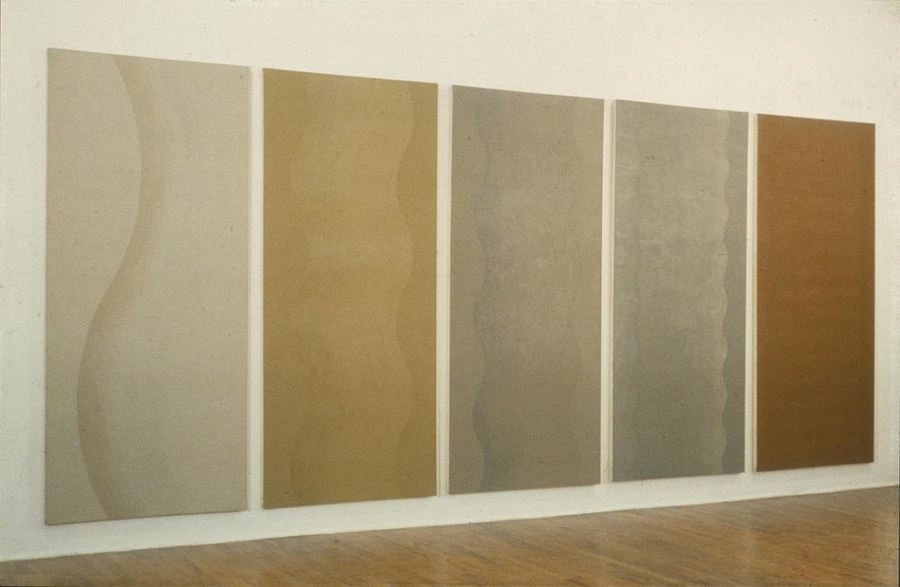

Lozano’s oeuvre includes two other major bodies of work. One is a series called the Wave Paintings, each oil-on-canvas work made according to a self-generated mathematical system that determined the number of waveforms in each painting. The relatively minimalist appearance of these conceptually derived paintings belies the task-based or endurance qualities of their production. Each painting was completed in one sitting, but the lengths of the sittings varied dramatically: “The 2 Wave, for instance, lasted only eight hours, while 96 Wave required three consecutive days of relatively uninterrupted labor.” The Wave series was mammoth, culminating in 192 Wave, which, once completed in 1970, marked the culmination of Lozano’s career as a painter.

Installation view: Wave Paintings, MoMA PS1, 1983

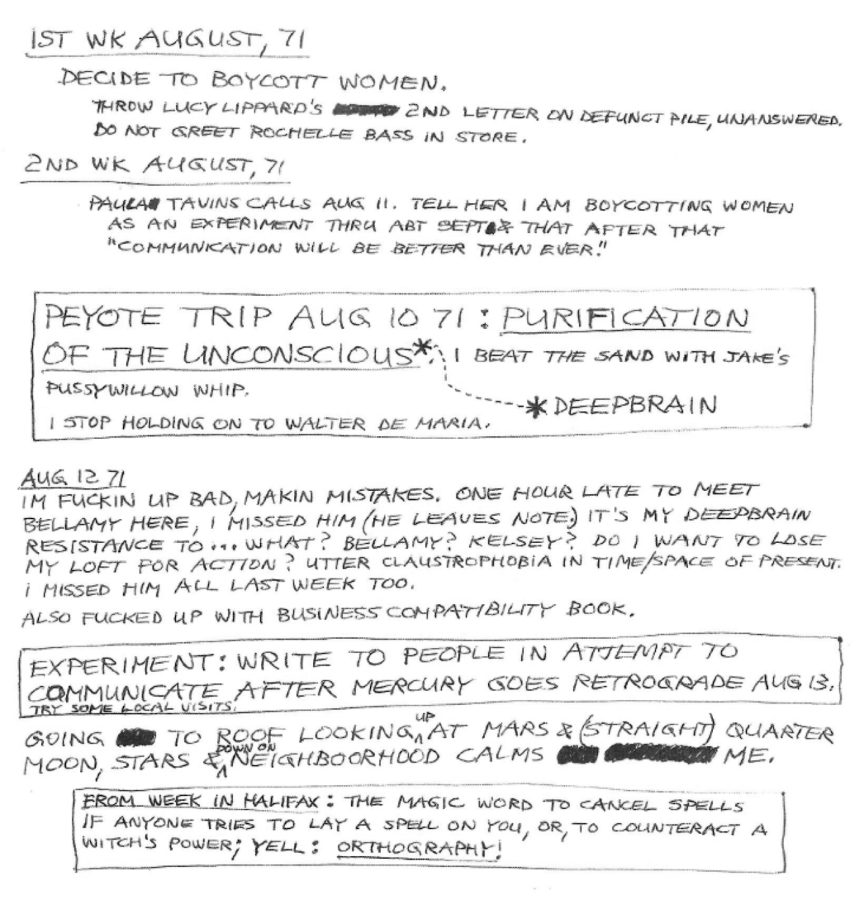

While Lozano painted, she also maintained a journal filled with what she called Language Pieces. Lozano was an early practitioner of Conceptual works; these, often handwritten, usually in block letters on graph paper, involved duration and the assignment of a task, or set of prescribed activities, for the artist to complete. Lozano’s notebooks are filled with instructions to herself—ranging from how much pot to smoke (as much as possible), to what to do with all printed announcements she received from galleries (throw them in a pile on the studio floor, or throw them out the window). Ultimately, she notes in her journal, she considers these works “drawings,” eliminating any distinction between them and her more traditional studio practice.

In many regards, Lozano’s most important Language Piece was the ongoing Dialogue Piece, started in 1969, in which she invited people into her studio for the sole purpose of discussion. While the journal notes have a certain voyeuristic appeal (the list of 1960s luminaries is remarkable), Lozano is quite particular about never divulging the specific content of the discussion, thereby drawing a line between the public and private dimensions of the work. So while Dialogue Piece operates in the tradition of the twentieth-century avant-garde, by exploring the increasingly porous boundaries between art and life, it also maintains a register of privacy associated with such work.

Dialogue Piece also typifies what I see as the primary thrust of Lozano’s work: the desire to use art to live a highly examined, and hence thoughtful, life. If one of art’s traditional roles has been to consolidate and focus attention and perception on an object, then Lozano used art to train her attention on the public and private functions of herself as an artist. In so doing, Dialogue Piece establishes several artistic aims: here, art is identified first and foremost as a vehicle to foster communication, so much so that dialogue is treated as a process to be valued over and above the production of a final object. That being said, the work uses art as a tool to give value to the ineffable quality of interpersonal relations, as opposed to bestowing value solely upon the world of objects. It follows then that in Dialogue Piece Lozano is deploying the category art as a force to legitimate a way of being in the world. This is why I think Dialogue Piece is structured around the artist’s studio: by exploiting her identity as “artist,” and the preestablished legitimacy of the studio as a space dedicated to the production of art, Lozano was able to establish that the most important aspect of artistic production and her life came together under the rubric “dialogue.” The category of art both permitted this activity and gave it a value it might not otherwise have had. To focus primarily on dialogue is also to focus almost exclusively on process as opposed to product (at precisely the moment pro-cess is entered into the downtown New York vocabulary), to such an extent that Lozano utterly slips out from under the problem of art as commodity. The utopian dimension of this project seems, in retrospect, utterly of its time.

These three bodies of work exhibit an extraordinary range of artistic interests and practices that confuse certain art-historical prejudices. Here is an artist who painted within the parameters of both Conceptual and performance art; who, when she painted in a brawling, figurative, expressionistic style, slipped under the wires of both the dominant painting styles of the day, Abstract Expressionism and Pop, and who all the while experimented with Conceptual art’s systematic refusal of the primacy of the visual in art. Well known at the time, Lozano had all of the markers of a successful New York art career: she showed at Greene Gallery; was reviewed in Art News and Artforum; was included in Lucy Lippard’s group exhibitions; and had a modest, one-person exhibition of the Wave Paintings at the Whitney. Another indication of both her art-world stature and her political leanings was her participation in the Art Workers Coalition. Asked to submit a statement for the small publication Open Hearing, Lozano put forward the following text:

For me there can be no art revolution that is separate from a science revolution, a political revolution, an education revolution, a drug revolution, a sex revolution or a personal revolution. I cannot consider a program of museum reforms without equal attention to gallery reforms and art magazine reforms which would aim to eliminate stables of artists and writers. I will not call myself an art worker but an art dreamer and I will participate only in a total revolution simultaneously personal and public.

In this 1969 statement, the utopian idealism of Dialogue Piece is extended even further. In her refusal to hold the category of art separate and distinct from other activities, Lozano exhibits a propensity toward critique. Her insistence on more comprehensive reform articulates a then-nascent idea that the art world is a complex system encompassing not only the museum but the gallery/magazine nexus as well. True to her word, concurrent with her reading the above statement at an Art Workers Coalition meeting Lozano was at work on her General Strike Piece. In a typewritten notation she stated: “Gradually but determinedly avoid being present at all official or public ‘uptown’ functions or gatherings related to the ‘art world’ in order to pursue investigation of total personal and public revolution. Exhibit in public only pieces which further sharing of ideas and information related to total personal and public revolution [artist’s emphasis].” And so her withdrawal and total revolution began. While some of the Languge Pieces were being shown, Lozano began to document her withdrawal from the art world, including her withdrawal from the political activities of the Art Workers Coalition, registered in part by a journal entry that describes her boredom and dissatisfaction with a subcommittee meeting of women involved with Art Workers at Lucy Lippard’s loft. Shortly after this encounter, Lozano wrote, “Decide to boycott women,” beginning a work that was to define the rest of her life.

I want to take a minute here to describe the terms of these simultaneous withdrawals. Lozano’s rejection of the New York art world meant that she left New York for Dallas, where she no longer attended art-world events or produced art objects. She continued her intense interest in dialogue, reading avidly and speaking to artist and dealer friends on the telephone. Her boycott of women was sometimes quite extreme; for instance, if confronted with a female clerk in a market she would insist upon being served by a man. However, not much is known about the three decades she spent in Texas, so it is difficult, if not impossible, to speak with any precision.

I want to hold her boycott of women and her withdrawal from the commercial art world in tandem. If one gesture is incredibly disturbing then the other is wildly idealistic, but both are structured by the principle of rejection, or refusal. Both things being refused are incredibly powerful parameters of identity. Lozano’s rejection of the subject position Artist, dependent as such a position is upon the bolstering paraphernalia and institutional legitimation of the art world, certainly evokes Marcel Duchamp’s famous refusal to make art for much of his artistic career. And like Duchamp’s, Lozano’s refusal to be a part of the art-world community, according to its “self”-definition, can be seen as an attempt to experiment with the limits or parameters of the categories of “art” and “artist.” Perhaps she was trying to test the limits of Dialogue Piece, to ascertain whether or not it was possi-ble to confer the value of art upon such activities without in fact engaging in any of the activities properly designated as befitting an artist? Clearly, without the institutions of art buttressing her activities Lozano fell into art-world obscurity, and this suggests that when an artist abandons the institutions of art, no matter how profound and legitimate the artist’s desire to merge life and art, the result will be that the “art” part of the equation will become unrecognizable. It is only now, with the excavation and attention of curators, critics, and art historians, that her work can be recognized and legitimated as such.

No title, 1971, ink on paper, 9¹⁄8 × 8½ inches

Yet Lozano’s refusal of the traditional definition of art was also bound up with a rejection of the category of artist as well. However, by yoking her commitment to a non-object-based practice to her disavowal of the institutions that demand commodifiable objects, Lozano was perhaps prescient in her understanding that, while the art world might one day embrace the nonsalable art object (consider the current status of much site-specific art), it would still need a commodity in the figure of the artist. In short, not only did she refuse to reify her artistic labor, she also rejected the equally calcified category of artist.

What does it mean to boycott women? Lozano’s use of words like “boycott” and “strike” evoke the Civil Rights Movement’s strategies of refusal to participate in systems deemed inequitable. Did she want to boycott women as a way of rejecting a socially constructed category, a subject position, a behavioral mandate, a predefined societal role, a presumed sexuality? I don’t know. But I’d like to suggest that Lozano’s refusal to speak to women implies an understanding of patriarchy that is akin to her rejection of the art world—both are systems, with rules and logics that are public with personal effects. Lozano realized that, just as you can’t reform the art world by focusing only on museums, you can’t alter patriarchy by bonding only with women.

If Lozano was using art as a way to enforce a heightened degree of self-awareness, then why did she reject categories that articulate and establish the boundaries of the self, categories as powerful as those of artist and woman? In many ways her rejection of these forms of identity focuses even more attention upon them. Not to speak to women is to render daily life a constant struggle, and I would proffer that in that space of difficulty Lee Lozano was more attuned to the problematics, limitations, and systematized nature of gender and patriarchy than most people on most days. And that, as I understand it, is one of the aims of feminist critique, to disallow the status quo to be perceived as natural, to heighten our awareness, to focus our attention on the problems of gender.

Perhaps Lozano’s aversion to the art world and to women was in part an aversion to ideas of community. Leo Bersani has argued persuasively that for all of the language of inclusivity, community is structured by the politics of exclusion.5 So, too, community implies a unified entity or group that prohibits internal debate; promoting a further calcification of ideas of external otherness, rather than privileging difference, community promotes sameness and affirmation. And I suppose that affirmation may be at the heart of the matter.

I think part of what is shocking about Lozano’s withdrawal is the rigor with which she rejected two intimately connected systems: patriarchy and capitalism. By refusing to speak to women she exposed the systemic and ruthless division of the world into the categories of men and women. By refusing to speak to women she acknowledged the impossibility of a life lived outside of the societal confines and projections of gender. By refusing to speak to women as an artwork she also refused the demand of capitalism for the constant production of private property. That she elided the fetishized art object and women was perhaps no mistake, as both share a similar fate.

The strategy of rejection is a powerful one, perhaps more so today than ever before, as the logic of late-capitalist culture is almost exclusively affirmative. To reject the space of culture, and to reject it in a gendered fashion is to demonstrate that the systems are linked, interdependent, and mutually beneficial. This is also the lesson offered by Virginia Woolf’s 1938 Three Guineas. In it Woolf argues passionately and acerbically with the writers of three letters, each of whom has requested philanthropic funds for noble causes: one to fund a women’s college, one to aid a women’s professional society, and one to help in the preservation of culture to help stop war. She responds to each similarly, by stating what about each cause she would reject outright—refuse the honorific degree, rebel against the trophyism of success in business, reject the nationalism around culture—and for each she makes the link between cultural philanthropic endeavors, “women’s causes,” and the need to develop strategies to resist and refuse the carnage of war. But the most important lesson of Three Guineas is Woolf’s articulation that the problem of war cannot be solved in and of itself, separate and distinct from the problem of women’s equality. She argues further that in order to solve the dual problem of war and women’s inequality, one has to identify the interconnected and mutually beneficial systems of patriarchy and capitalism and then to reject their self-imposed terms of engagement. Lee Lozano did just that, and in keeping with current conditions of critical public discourse under late capitalism, her refusal to play by the rules feels simultaneously utterly pathological and consummately idealistic.

Published on the occasion

of the exhibition at

Karma

188 East 2nd Street

New York, NY 10009

Edition of 1,000