September 13, 2017

Louise Fishman published by Karma, New York, 2020

Download as PDF

Louise Fishman is available here.

Louise Fishman’s A Little Ramble (2017) is oceanic and atmospheric, aqueous and gaseous, watery and airy at once.

At first read, you might think I’m saying this because the painting is overwhelmingly, luxuriously blue, the color of sea and sky and many things besides—but that’s not it. Yes, there are blues—ranging from pale, transparent blue-green to deep teal to ultramarine to blue-black— but there are also forest and drab greens, whites, umbers, and even, if my eyes don’t deceive me, bits of red.

Each of these pigments has a distinctly different coloristic and optical effect depending on how it is applied—whether troweled on thick as plaster by a wide knife, dragged by a scraper across the nubby canvas, diluted and painted in thin washes, squeezed directly from the tube, pressed on using a bit of paper, cardboard, or strip of painter’s tape, at times left in place, at others peeled off, leaving an irregular, raised pattern behind (the Surrealists called this technique decalcomania), or laid on in one of the myriad other ways that Fishman manages to get paint on canvas. The surface is the site of an endlessly fascinating array of light effects as a result, ranging from transparency to opacity, from matteness to opalescence.

Louise Fishman, A Little Ramble, 2017, oil on linen, 70 × 90 inches; 177.8 × 228.6 cm

This play of color, brushstroke, and luminosity—and there is, in Fishman’s work, a strong sense of play, of contingency, of the give and take that comes from one painterly decision opening up possible next moves and foreclosing others, which results from her improvisatory, process-driven method of painting—is counterbalanced by the grid, a constant presence in her oeuvre. Fishman’s grid functions not so much as a predetermined scaffold but as an always emerging specter: she does not start with the grid; it develops through an intuitive process of mark-making. Every time she makes a move, applies a block of color, or scrapes it down again, a matrix surfaces on her canvas; yet when we try to pin it down, to trace its horizontals and verticals, to see it as a form in and of itself, it disappears and all we can see are those marks, the blocks of color, the scrapings.

Most of her mark-making in A Little Ramble, as contingent as it is, whether comprising broad swaths or narrow lines, application or incision, is rectilinear, following the edges of her support. But there are moments—just moments—where something else happens: white paint applied in an arcing stroke in the upper-right corner, or scrubbed into the surface at the top of the greenish patch lower down, or watery dark blues staining the canvas in big blobs. The effect strikes me as akin to the Renaissance technique of sfumato—a softening, a haze, a fog, as if the clouds have descended. A smoky incursion into an otherwise orderly space. A form of mark-making that is also a sort of erasure.

Fishman’s painting does and undoes the grid. The paint—like air, like water—cannot be contained, or can, but only provisionally.

•

A Little Ramble—like all of Fishman’s paintings made since 2011, the year of her first extended stay on an artist’s residency at the Emily Harvey Foundation—is marked by her experience of Venice.1 Venice signifies for the artist in many ways: she speaks of the algae-mottled plaster and crumbling stone and brick of the walls of the city; the soaring architecture of the churches; the art of Titian and Tintoretto and other masters of the Venetian Renaissance; views of the city painted by the nineteenth-century English landscapist J. M. W. Turner; the quality of the air and light, which she describes as having an almost physical, substantial presence—she doesn’t use the word ether, but that’s the closest analogue; and, of course, the water, which has determined and defined the city’s form for centuries and constantly threatens to overwhelm it.

You can find all of these references in Fishman’s paintings if you look at them in a certain fashion—the horizontal disposition of many of her rectangular canvases predisposes us to see them as landscapes or cityscapes or seascapes, to read narrative into abstraction. But all these readings-in, it seems to me, speak not to what the paintings mean, but to what they do. Fishman’s recent works enact what might be described as the overwhelming of form by entropy: a city eroding from water and age; disegno (drawing—but also rationality, intellectualism, structure—a mark of the Florentine Renaissance) dissolved under the pressure of colore (color—but also passion, the organic, emotion—a specialty of the Venetians); the undoing of the underlying subject in Turner’s nature studies by his energetic brushwork, his dedication to capturing the play of light and the particularities of atmosphere revealing the world as an abstraction.

•

Fishman’s artistic formation included exposure to art and artists at an early age thanks to her mother, Gertrude Fisher-Fishman, and her paternal aunt, Razel Kapustin, both painters who studied at the Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania, and spent endless hours at the Philadelphia Museum of Art with young Louise in tow. It continued with her rigorous study of both studio art (painting and sculpture) and art history at the Tyler School of Art in Elkins Park and then at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

By the time she arrived in New York in 1965 she had what she describes as the naive belief that she would become an Abstract Expressionist. For her, Ab Ex—not just as an approach to painting, but as an ethos—seemed to align with her sense of being on the margins: “I saw all those painters as rogues, outside the normal course of things,” she once said. “I knew by the time I got to art school that I was a lesbian … I felt that Abstract Expressionist work was an appropriate language for me as a queer. It was a hidden language, on the radical fringe, a language appropriate to being separate.”2 She laughs now at her youthful folly: it didn’t take her long to discover that being part of the New York Ab Ex world would only be possible were she a man or willing to sleep with one.

So she turned her attention for a while to the other dominant artistic language happening in avant-garde circles in New York—Minimalism—and began making hard-edged paintings that had as their basic structure the grid. She had experimented with the format in graduate school, thanks to the influence of Al Held’s work, which she had seen in the galleries of the Art Institute of Chicago; in New York, Sol LeWitt and Ellsworth Kelly were added to the mix.

As Fishman gained consciousness of her position as an out queer woman living in a sexist world, she became drawn into the women’s liberation movement. However, as with her experience with the Ab Ex crowd, mainstream feminism treated her as an outsider: her queerness (and, in some instances, her status as an artist) kept her at the edges. She tells a story about pushing into a feminist art meeting and suggesting a consciousness-raising exercise, a tool of radical feminist organizing in its early years. Everyone agreed, and greeted other women’s testimonies in vocal and supportive ways. When it was her turn, Fishman declared “I am a lesbian and I am a painter.” The group fell silent. “I was completely ignored and without missing a beat, they carried on. They didn’t know what to do with me,” she says now. She found her footing in a specifically lesbian feminism, a radical one, and, starting in the later sixties, began to meet with a group of artists, writers, and thinkers: during the summer of 1969, she met weekly with Patsy Norvell, Tricia Brown, and Carole Gooden, and come the fall of that year, she began meeting with Norvell and a group of Norvell’s artist friends, who lived in and around SoHo.

It was at this time that Fishman began to see her painting clearly through the lens of her politics. She describes this phase as one of “wanting to get all the male stuff out of my painting”—wanting, that is, to unsee and unlearn what she was now recognizing as an exclusively male history of her chosen medium. Encountering Eva Hesse’s work for the first time, she recognized the sculptor’s attempt to refashion Minimalism by combining its industrial repetition, modular forms, and gridded structures with unconventional materials—string, fiberglass, rubber, etc.—that suggested the body’s fragility and capacity for decay. Fishman saw this approach, one based on a material experimentation and formal play, as a clear challenge to the maleness of the avant-garde. Hesse gave Fishman permission, as she tells it, to “do whatever the fuck I wanted”—to be in that very space of outsideness that her gender, her sexuality, and her political commitments had pushed her, and find a productive home there.

So she began to experiment with new materials and techniques. This period in her work—from roughly 1969 to 1973—was one of undoing: of rejecting painting, at least momentarily, in some cases by literally cutting up her canvases and sewing them back together as combines or collages. The grid was still there, and would continue to be, but it was now no longer Held’s grid or LeWitt’s grid or Kelly’s grid—it was thoroughly and completely her own.

•

In her most recent works, the grid arises in multiple ways, but never claims primacy—in Fishman’s nimble hands, almost as soon as it emerges, it dissolves under the pressure of color and gesture, making way for a sort of airiness or adding an optical density, by turns.

Piano Nobile (2017) is, relatively speaking, fairly completely covered in paint, and yet it respires to an extraordinary degree. The air in Fishman’s paintings is not the result of emptiness, of bare canvas showing through between the masses of paint, but is a matter of color, of a sort of openness of touch on the surface, of a certain softening of edges. The painting is composed of blues and blue greens and coppery browns and ochre and red and—unexpectedly, and delightfully—one patch of the purest purple. Fishman also serves us a generous helpingof white, which exists both in its own right and as an incursion into the other patches of color, tempering and blending the rectilinear design. Piano Nobile is all about layers—the red remains on view despite the dun brown (a noncolor, an admixture of too many hues at once) that is painted atop; the blues and grays and olives drip over and through; the drag of a wide spackle knife excavates dried underpainting here, deposits lips of pigment there. The result is almost startlingly sensual—and at one point becomes quite literally tactile, when we see that her fingers have gotten into the act, dragging ultramarine in short strokes in the lower-left quadrant of the canvas. The massing of the colored blocks on the surface seems distinctly architectural—it would not be out of line to see a cityscape in this abstraction (not least because of the title, which refers to the main floor of a palazzo)—but they also seem to signify water and light: all that is solid melts into air, into reflection, into luminosity.

Louise Fishman, Piano Nobile, 2017, oil on linen, 70 × 90 inches; 177.8 × 228.6 cm

Louise Fishman, Mon Semblable Mon Frère, 2017, oil on linen, 50 × 30 inches; 127 × 76.2 cm

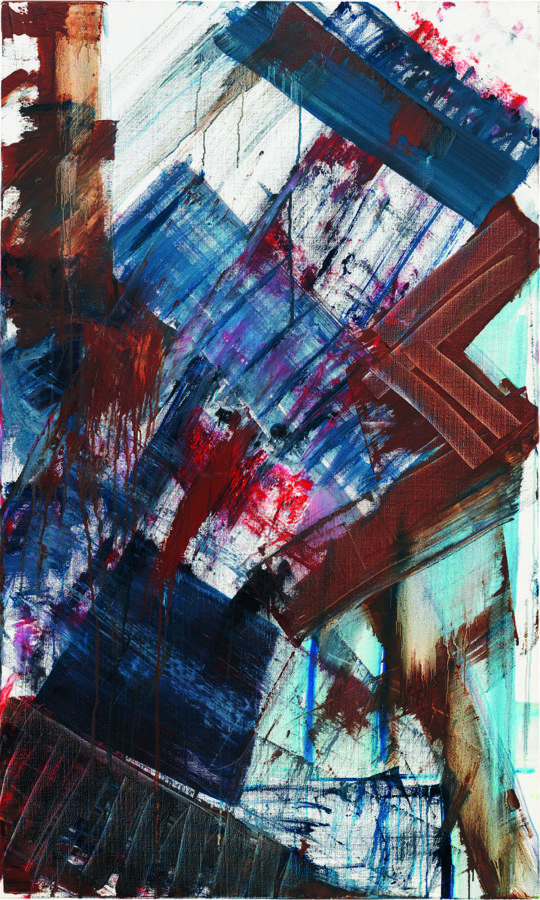

The incursion of the diagonal and the curve, when it happens in Fishman’s new paintings, is striking for exactly the reasons you might expect: the careful stasis of the rectilinear becomes dynamic, agitated, and organic by turns. Mon Semblable Mon Frère (2017) is a case in point. The grid is now twisted, so that it maps a vertiginous, canted, three-dimensional space despite sitting resolutely on the surface of its rectangular support. The canvas is smaller than usual, a narrow vertical, and the palette is somber—dark blues, burnt sienna, umbers, and reds, with the leavening effect of a transparent sky blue at points. Fishman speaks of the soaring spaces of churches in relation to some of her recent work; to me there is something more urgent and more driving about Mon Semblable Mon Frère than that. This is no sanctuary. It is the city as revealed by Aleksandr Rodchenko’s or László Moholy-Nagy’s constructivist photography—made strange, turned into an abstraction, thanks to the handheld camera’s capacity to look at the world askew, from above and below and sideways. This same energy is apparent in Cadence, a larger canvas whose structure likewise depends on oblique angles and a heavy scaffold. But here, because of the scale of the canvas, it is less photography that is at issue than the slashing, energetic, even athletic brushwork of Franz Kline, one of Fishman’s early and most significant influences.

The title Mon Semblable Mon Frère (“my likeness, my brother”) comes from the preface to Les Fleurs du mal by the French poet Charles Baudelaire, who called out his readers (“Hypocrite reader, my likeness, my brother!”) for not recognizing that the immorality that his poetry was judged to enact, which led to its censoring, was simply a reflectionof the world, and thus was theirs, too. It was an accusation subsequently quoted by T. S. Eliot in The Waste Land—a lament about the disintegration, decay, and dissolution of the modern city. Here is where entropy gives way to something more sinister—degeneration, a cultural malaise, a decadence. This painting contains precisely that pathos.

And look how Fishman manages to eke out this pathos—but now, in a more brittle form, one that comes from eyes that have seen it all—in a painting whose palette is reduced to black and white. As we looked at Sharps and Flats (2017) together, the artist said she’d given it a boring title. It seemed out of sync, she said, with the jagged, jangly effect of the whole: strong horizontal groundlines that run across the middle register of the canvas, countered by strong, vertical, punctuating marks, some of which veer off at an angle, adding a sort of velocity to the composition. But even if Fishman doesn’t recognize her own poetry, her viewers can revel in it: think of the way the words “sharps” and “flats” roll around on your tongue, the spitted “p” of one and “ts” of the other; think of the musical effects of sharp and flat tones—pathos and bathos by turn, dissonance and melancholy.

The curve was not a natural part of Fishman’s repertoire; it was something she had to learn (or relearn), in recent years. When it appears—as it does, spectacularly, in San Stae (2017)—we are reminded again of the athleticism of her method: the way in which each of the marks on her large canvases—rectilinear or not—is made by a body reaching across a surface as big or bigger than her span. Fishman was a basketball player in her teens, and that experience continues to inform how she thinks of the act of painting: the basketball court as an analogue for the rectangle of the support, the tactical and intuitive movements that allow her to react to what has happened and anticipate her next move, and the sheer physicality of wielding her tools across an expansive surface are somehow connected to this latent muscle memory.

Where other painters might imagine the grid as an external structure, projected onto the canvas or the world to allow the viewer to make sense of it as other to themselves, a way to map a space out there—Rosalind Krauss famously described it as “antinatural, antimimetic, antireal”3—Fishman operates from within the grid, just as she operated in the basketball court. It becomes a product and an extension of her body, rather than a predetermined given, and she makes it and unmakes it from within. On her terms.

NOTES

1 In addition to extensive conversations with Louise Fishman and Ingrid Nyeboe in April and May 2017, I relied on a few excellent texts on Fishman’s artistic evolution in preparation of this essay. These included the essays in: Helaine Posner, ed., Louise Fishman, (Purchase, NY: Neuberger Museum of Art; Philadelphia, PA: Institute of Contemporary Art; Munich: DelMonico Books/Prestel, 2016), especially that by Helaine Posner (“Louise Fishman: The Energy in the Rectangle,” 11–21); and an interview with Sharon Butler published in The Brooklyn Rail, October 4, 2012, https://brooklynrail.org/2012/10/art/louise-fishman-with- sharon-butler.

2 Louise Fishman, in Holland Cotter, “Art after Stonewall: Twelve Artists Interviewed—Louise Fishman,” Art in America 82, no. 6 (June 1994): 59–60. Quoted in Posner, “Louise Fishman: The Energy in the Rectangle,” 12.

3 Rosalind Krauss, “Grids,” in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986), 8–22. Originally published in October 9 (Summer 1979), 50–64.