November 3, 2020

Louise Fishman published by Karma, New York, 2020

Download as PDF

Louise Fishman is available here.

When asked whether she considers herself a second- or third-generation Abstract Expressionist, Louise Fishman blithely replied, “I consider myself an abstract painter.”1 And who could blame her? Who wants to be considered “second” or “third” in anything? Especially if, like Fishman, you were once a competitive athlete. The frame of the question, though, succinctly points to some of the long-standing problems with the linear, chronological accounts that have traditionally shaped the histories of twentieth-century visual art, and which have long privileged the earliest moments of perceived artistic “invention.” As the Museum of Modern Art’s Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture, Ann Temkin, has remarked, extant modern art histories, up until very recently, have often been told as a series of “firsts,” with one concept sequentially supplanting another. The genesis of this methodology, she surmises, relates to the field’s earliest connections to the histories of science, which turned on notions of progress and innovation. However, the discipline’s heavy emphasis on these “firsts” or “eureka” moments, has, among other consequences, often led to the shuttling aside of an artist’s later career accomplishments, which, as Temkin says, “is sort of like focusing on the tip of the iceberg.”2 Art history’s “fascination with youth,” which she offers up, too, has often been “unconsciously applied” to the organizing strategies used to determine how MoMA’s team would hang works in its permanent collection galleries and which works they chose to present. By extension, it was implied, though not stated, that this then affected which artists they initially chose to collect. Such teleological approaches to art history have also led to the exclusion of many artists, who either appeared later onto the scene, or who have been systematically marginalized over the course of many decades due to their gender, race, sexuality, age, or some combination thereof. As a result, the achievements of so many significant female artists, artists of color, and gay, lesbian, or queer artists have remained absent from mainstream museum collections and art historical narratives. This situation, importantly, has started to change in the past ten years, and is still productively in flux, as many museums and academic institutions are engaging in concerted efforts to rectify past exclusions and redescribe modern and postwar art histories along thematic axes and across bidirectional time frames, expanding entrenched narratives that have strongly favored a small group of white, male artists.3 Among the most dynamic reevaluations currently underway pertain in particular to the histories of Abstract Expressionism and its legacies, wherebymuseum curators, galleries, and academics alike are beginning to foreground a wider array of figures, across broader time spans, both in the United States and abroad.

Which brings us to Louise Fishman. Appearing much younger than her eighty-one years, Fishman possesses a notable physical vibrancy and self-assurance. She is, more importantly, still as ever a powerhouse of an abstract painter, with a flourishing, late-career artistic practice. Indeed, Fishman arguably has made many of her best paintings in the last twenty years—which is to say, since turning sixty. Through the decades, she has continually developed her own highly individual and experimental approach to painting, which, while evolving over time, always succeeds in deftly commingling the gestural mark-making of Abstract Expressionism with the rigid geometries and modular structures of Minimalism. In so doing, she brings two art movements generally understood as antithetical to one another into the same orbit. Yet despite, or perhaps because of, her redefinition of such historical terms, her creative trajectory thus far has not clearly aligned with dominant versions of postwar art history, and she has yet to receive the higher level of institutional recognition her work warrants—which, perhaps, may also not come as a great surprise, given her position as a woman, a feminist, and a lesbian Fishman, who was born in 1939 and came of age in the late 1950s and early 1960s, is a peer to such highly celebrated figures as Brice Marden, Eva Hesse, and Robert Mangold, as well as to artists who are somewhat lesser known by comparison, such as Judy Chicago, Mary Corse, Suzan Frecon, Sam Gilliam, Mary Heilmann, Howardena Pindell, Pat Steir, and the late Jack Whitten, whose careers, like her own, have all recently started to receive long-overdue museum and market attention. Moreover, given Fishman’s extraordinary productivity since the early aughts, it is interesting, too, to consider her accomplishments in relation to a younger generation of mid-career painters, such as Jutta Koether, Jacqueline Humphries, Amy Sillman, and Charline von Heyl, whose works have contributed to meaningful twenty-first-century discussions about the renewed relevance of hand-crafted, abstract painting in the context of our digitally dominated present.

While growing up in Philadelphia, Fishman, more than most children, had exposure and access to art: both her mother and aunt were themselves talented painters. Consequently, copies of Art News and other relevant art magazines were always lying around her house, and nearby were the incredible permanent collections of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Barnes Foundation, which she frequented. Thus, at an early age, Fishman was able to experience firsthand the remarkable still life paintings by the eighteenth-century French artist Jean-Baptiste Sim.on Chardin and the late-nineteenth-century landscapes by Paul Cézanne, as well as the early-twentieth-century expressionistic scenes by Chaim Soutine and the dynamic gridded compositions of Mondrian—all of which excited her.

Nothing, though, was more exhilarating than the Abstract Expressionists. Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock, and Willem de Kooning were the ones she most admired; however, even in the mid-1950s when Fishman herself was headed to art school, their work was still primarily accessible only through magazines and newspapers. Although these painters were among the art stars of their time, they were not yet broadly embraced by museums or art academies. For Fishman, though, the effect of these artists’ paintings was profound: “I was an abstract painter from the start, and it was abstraction as much as painting that thrilled me. … I saw all those painters as rogues, outside the normal course of things. I knew by the time I got to art school that I was a lesbian … I felt that Abstract Expressionist work was an appropriate language for me as a queer. It was a hidden language, on the radical fringe, a language appropriate to being separate.”4

By the time Fishman completed graduate school and moved to New York City, it was 1965, and although she was steeped in the painterly mode of gestural abstraction, she was quickly drawn to the blossoming downtown art scene, where Minimalism was ascendant—a movement whose visual tropes and rhetorical framing was in stark contrast to that of the Abstract Expressionists. Against this backdrop, the geometries of Al Held, Ellsworth Kelly, and Sol LeWitt soon became important influences on Fishman’s work, evident in a number of boldly colored, hard-edged paintings she created in the mid-1960s as well as in works from several years later in which contrasting colors appeared as pulsing rhythms of vertical bars (Untitled, 1967, and Untitled, 1970) or as vibrantly criss-crossing plaids (Untitled, 1968). The latter were among Fishman’s first engagements with the “grid,” whose structure would henceforward be an ongoing compositional touchstone in her work.

Fishman’s exposure to the work of Minimalist and Post-Minimalist artists coincided soon thereafter with the intensifying social and political ruptures of the late 1960s, which would ignite an even greater change in her artistic development. By 1967, Fishman had become emmeshed in the nascent feminist and gay rights movements evolving in New York, participating in such radical feminist groups as the Redstockings (Redstockings of the Women’s Liberation Movement) and W.I.T.C.H (the Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell), as well as leading various consciousness-raising groups herself. It was through her activism that Fishman became close with other lesbian women at the forefront of the New York movements—many of whom heralded from cultural fields beyond the fine arts, such as film, journalism, dance, and anthropology—and their divergent perspectives had a profound impact on her. Responding to the emphasis on writing and journal-keeping in these groups, Fishman began creating works between 1967 and 1971 that took on comparable characteristics. Some were square formats of stained acrylic on canvas, comprised of almost translucent, contrasting colors arranged in graduated strata and reflecting a mark-making system analogous to an abstract cursive (Untitled, 1970). Many works from this time, too, are smaller-scaled works on paper, with compositions that often closely resemble the pages of an open book (Untitled, 1971); while others foreground matrix-like compositions, which also inherently evoke the written word (Untitled, c. 1967).

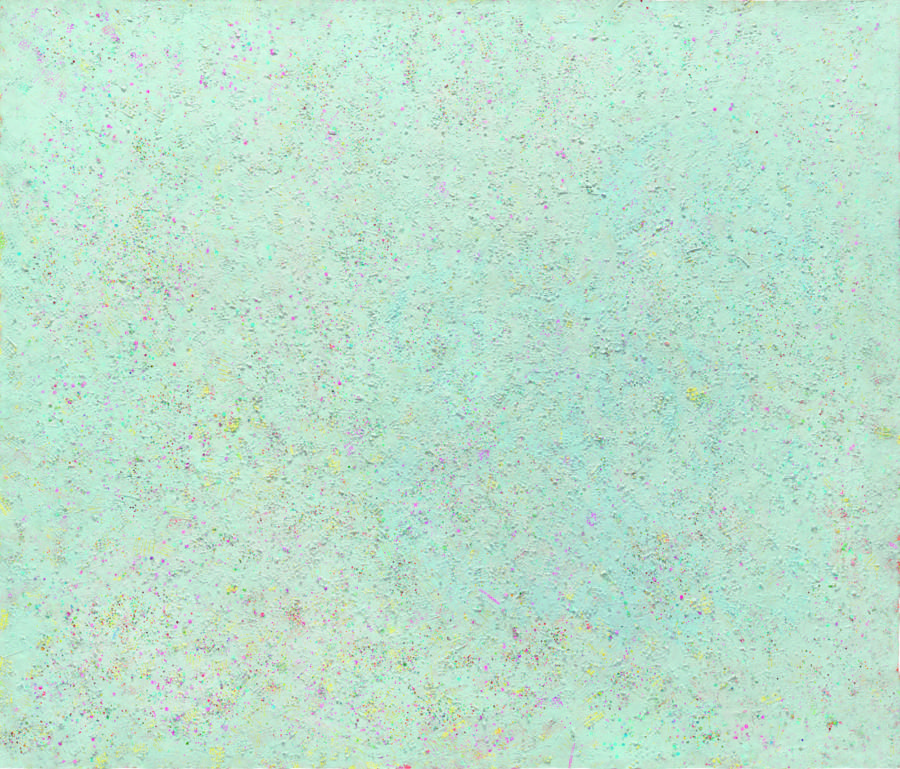

Howardena Pindell, Untitled, 1977, mixed media on canvas, 83 1⁄2 × 99 inches, 212.1 × 251.5 cm

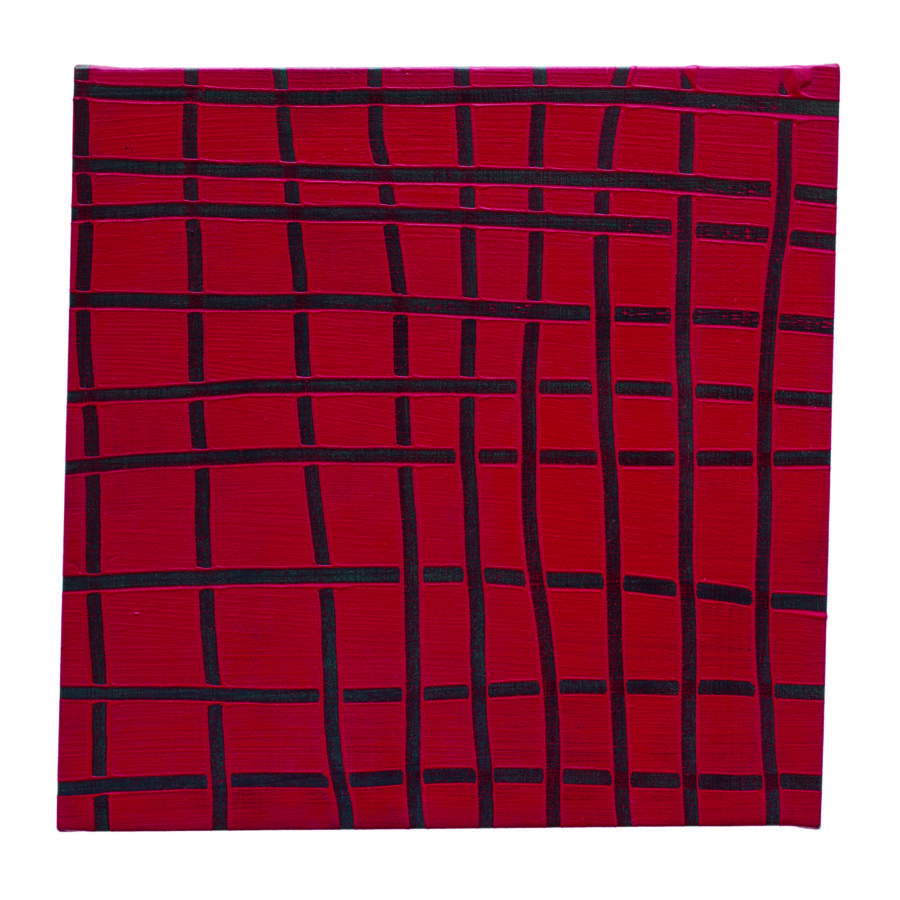

Mary Heilmann, Little 9 × 9, 1973, acrylic on canvas, 21 7⁄8 × 21 7⁄8 inches, 55.6 × 55.6 cm

As the women’s rights movement gained momentum in the next several years, Fishman’s participation in it prompted her to question further, in very fundamental ways, how she was making art. Like many of her feminist artist peers in the early 1970s, Fishman abandoned altogether making oil paintings on conventionally stretched canvases—generally considered to be a “male” mode of art-making—and instead turned to techniques and materials traditionally associated with women’s work, craft traditions, the handmade, and the domestic realm. Fishman herself adopted several experimental approaches involving processes of dying, staining, and tearing unstretched canvas swathes. These strips were then sewn or stapled together, resulting in intimately sized, quiltlike textile works whose horizontal thrusts of stitched, threaded, and knotted string equally conjured up cryptic ancient scrolls. Often executed in elegant graphite grays, or, in other cases, flesh-colored rubber, these pieces hang on the wall like sculptural paintings, while also retaining a connection both to the modernist grid and the printed page.

Fishman’s irregular, latticed assemblages from this time reveal a relationship to the earlier anthropomorphic serial forms of Eva Hesse, while also sharing a connection to contemporaneous gridded paintings by Howardena Pindell and Mary Heilmann. While Heilmann’s paintings featured irreverently lilting and dripping geometries, executed in hot pinks, acid greens, and other unexpectedly brash color schemes, Pindell, by contrast, created highly nuanced mixed-media paintings by gluing thousands of hole-punched, colored paper dots onto swathes of unstretched canvas, creating abstract fields of feminine pastel colors, under which glimpses of pencil-drawn matrices could be found. Though the works of these artists are highly distinct, each demonstrates related tactics of infiltrating the predominant artistic vocabularies of 1970s Minimalism, in order to infuse them with new feminist associations.

Like Pindell and Heilmann, Fishman, with her latticed works, not only plays off of the grid’s status as arguably the most iconic modernist composition, but also expresses its inherent contradictory possibilities. As Rosalind Krauss has described, the grid simultaneously inhabits two prevailing, and opposing, vectors of modernism. Part of the grid’s “mythic power” is its capacity to signify, on the one hand, a sense of materialism or concepts related to science or logic, while, on the other, effecting a “release into belief ” into the realm of illusion.5 This “release into belief,” as Krauss explains, can be associated with universalist ideals, as it was, for instance, for Mondrian in the early twentieth century, or with spiritual concepts, as it was for the grid-based work of Agnes Martin several decades later.6 While both of these earlier figures were big inspirations for Fishman, her own compositions are rarely tethered to the matrix structure of the grid itself. Rather, Fishman’s entanglements with the grid, however varied throughout her career, reveal an interest in exploring ideas about individuality and subjectivity. Identifying as feminist while also participating in abstract painting modalities associated with Modernism, Fishman, alongside many of her peers, began to extend the familiar feminist mantra, “the personal is political,” into the nonobjective realm.7

Although positive momentum of the feminist and gay rights movements continued to build around the country, frustration at the individual and collective level also escalated among Fishman and her peers. In the art world, countless women artists continued to be excluded from most mainstream museum and gallery opportunities. Even Fishman’s appearance in the high-profile Whitney Biennial of 1973 did not, she believed at the time, immediately change her own situation in an appreciable way. (In reality, one year later, the artist actually did go on to have her first New York solo gallery exhibition, with Nancy Hoffman Gallery, which continued to represent her through the 1970s.) Fishman’s intense disenchantment with the art world at this time turned out to be the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back, provoking what would eventually become her next significant body of work. In an impulsive moment of fury, Fishman spelled out in large, capital letters, “ANGRY LOUISE,” with “serious rage” scrawled below, all enveloped in a swarm of bruised and violent scribbles. Although Fishman had integrated charged, written inscriptions into her abstract compositions a year or two earlier in such works as Louise Five Times (1972), or the multipaneled Letter to My Mother About Painting (1972–73), ANGRY LOUISE was a marked departure for the artist. If these prior works literalized words and writing, ANGRY LOUISE more closely invoked “speech”—a loud, screaming painting: the volume dialed up all the way.

In the days and months thereafter, a frenzy of similar painted “portraits” on paper followed: first, based on Fishman’s lovers, female relatives, activist friends, and art-world figures, and then expanding to include famous feminist leaders and lesbian icons from different time periods and cultural realms whom she admired but never knew. The nineteenth-century British writer Radclyffe Hall, for example, shares space with Marilyn Monroe, the choreographer and filmmaker Yvonne Rainer, gallerist Paula Cooper, and anthropologist Esther Newton. Angry Gertrude. Angry Jill. Angry Marilyn. Angry Sue. Angry Esther. Angry Paula. Angry Yvonne. Angry Ti-Grace. The cavalcade continued until there were more than two dozen paintings in all—each with its own teeming, Technicolor palettes and vigorous patterning intended to match Fishman’s vision of each woman’s personal outrage. With their high-octane expressive gestures, these works are akin to blaring signs of protest; even their proportions and bold printing echo the handwritten, hand-carried signs from the anti-war, pro–gay rights, and other protest marches of the era. In their multitude, the works are surrogates for a mass of shouting demonstrators. And yet, they also move beyond cacophonous fury and equally elicit an implied sense of common cause, suggesting the possibility for expanded community, if only an imagined one.8

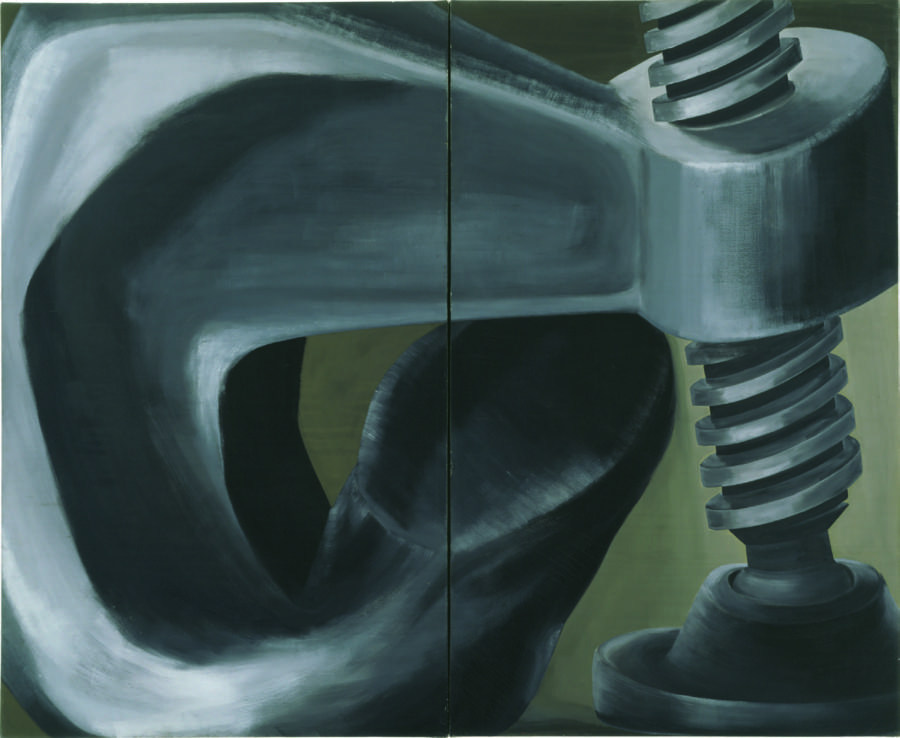

The raw emotion and anti-commercial look of Fishman’s Angry paintings recall other feminist artistic actions of the era that critique aspects of the established, male-centric art system, and its preference for marketable objects. The surreal, harrowing drawings and provocative paintings from the 1960s by Lee Lozano depicting human body parts, giant anthropomorphic tools, and irreverently erotic remarks come to mind, to say nothing of Lozano’s more extreme, conceptual, performance-based works that followed soon after. The Angry paintings, too, in their raucous polyphony, are also a salient precursor to the infamous Dinner Party installation by Judy Chicago, created in 1974–79, which similarly summons a pantheon of female figures from wide-ranging eras. Among the 1,038 women mentioned in The Dinner Party, thirty-nine receive central attention at a monumental banquet table, each represented by a unique, intricately designed, ceramic place setting incorporating stylized vulva forms and other elements of female iconography. While Fishman’s simple means and improvised gestures are in obvious dramatic contrast to Chicago’s epically scaled, collaboratively produced enterprise, both Fishman and Chicago make visually explicit connections to figures from historical moments other than their own, and, in turn, actively situate their works in a broader world. In this way, both artists reimagine past and present, inscribing themselves into a constellation of association, and reflecting what Catherine Lord has described as “the feminist ethos of subverting traditional hierarchy in order to propose other histories.”9

For the five years following the initiation of the Angry series, Fishman continued from 1974 to 1978 to extend her sense of formal play, further experimenting with a cut-and-assemble, collaged aesthetic, as she began to create works from found scraps of wood or cast-away bits of cardboard. With an insouciant, rough-and-tumble informality, these wax and oil paint works were often irregularly shaped in their outer contours, primarily monochromatic, and possessed a layered dimensionality. Works such as Caryatid (1974), St. Lucy, Martyr (1974), Untitled (1974), and Artemis Who Rejected All Lovers (1974) illustrate, too, how compositions during this era were often defined by geometrically shaped fields of subtle color shifts, ranging from viscous bluish grays and blacks to warm, luscious browns.

By the end of the 1970s, though, Fishman decided to return to the traditional form of oil painting on canvas, which was a contrarian move for the time. Gestural abstraction was looked down on by the Minimalists and the feminists alike, while also having fallen out of favor in other artistic circles such as the so-called Pictures Generation, who championed techniques of photographic appropriation. With Fishman’s return to painting in 1978 came a distinctly looser engagement with the “grid,” one more fluidly combined with highly personalized brushwork. Spanish Steps (1979), Ashkenazi (1979), and Guidecca (1980) all reflect these stylistic developments with their thick, impasto surfaces organized by casually tessellated and suggestively architectonic compositions. Importantly, too, Fishman began experimenting rigorously with new techniques, expanding her process-based approach by developing a personal arsenal of palette knives, plastering trowels, gardening spades, rollers, and scrapers with which to approach the canvas, alongside the expected brushes. Surfaces began to evolve over an extended period of time, as Fishman built up interweaving layers of pigment, only to later scrape them down and construct them once again.

Lee Lozano, No title, 1964, oil on canvas, 108 3⁄8 × 132 1⁄2 inches, 275.3 × 336.6 cm

The artist often describes her approach to painting as almost sculptural, handling paint as if it were clay—a vantage she generally ascribes to her early study of sculpture and ceramics as an undergraduate at Tyler School of Art and Architecture. Many of her paintings from this era possess this type of viscous, tactile surface materiality.10 Such methods were continually refined, often to elegant, atmospheric effect, as evident in Steel Pier (1986–87) with its serenely hatched, palette-knifed passages of misty grays and muted teals intermingling with tampered browns and scumbled whites. Other examples such as Cinnabar and Malachite (1986), emphasize a more earthbound physicality and vigorous temperament, with muscular paint application and crystalline luminosity. The painting’s title, too, reminds us that the eponymous minerals, excavated from the earth, are the base for painting’s pigments, a material relationship to which Fishman was always strongly aware.11

Sparked by her relocation to a rural area in upstate New York in 1987, where the artist primarily lived for the next decade, Fishman’s paintings from the next couple of years accentuated her new relationship to her natural surroundings, taking on colors and textural qualities associated with trees, rocks, fields, and soil. Perhaps the most noteworthy group from this time period was also inspired by a 1988 trip the artist took to the World War II Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camps in Poland, at the invitation of a friend who was a Holocaust survivor. References to Fishman’s Jewish heritage had periodically surfaced in her works since the mid-1970s, often in her culturally specific titles. Growing up in a conservative Jewish community, with a grandfather who was a Talmudic scholar, Fishman was always engaged with Jewish history, although she has never been very religiously observant. However, this emotionally harrowing trip to the concentration camps triggered what would become a cycle of nineteen paintings that directly engaged her Jewish heritage. To create these works, Fishman mixed into her paints beeswax combined with tiny amounts of silt she had collected from the bottom of the Pond of Ashes, where the remains of many thousands of gassed and cremated Jews were deposited. Titled Remembrance and Renewal, this series forms a contemplative, somber invocation honoring the collective memory of the multitudes who perished during the Holocaust. These paintings also contain inklings of renewal and growth: dark, mossy greens and rich, mulchy browns permeate the compositions, while their titles, moreover, refer to Jewish prayers and rituals associated with the springtime tradition of Passover, such as Four Questions (1988), Haggadah (1988), or Bitter Herb (1988). Taken as a whole, these works also explore how notions of identity can surface in abstraction.

The next development in Fishman’s work followed shortly thereafter. In 1990, a devastating fire in her upstate studio destroyed many works, tools, and equipment, launching Fishman into a dark tailspin. Depressed and unable to work, she decided to take a return trip to New Mexico, where she had once traveled years before. The expedition turned out to be a healing pilgrimage of sorts, as Fishman visited the area of New Mexico where Agnes Martin then lived, and after bravely writing a letter to the artist she had so long admired, was granted permission to visit Martin at her adobe home. Spending time with the elder artist was inspirational to Fishman, who was moved by Martin’s peaceful demeanor and equally serene domestic and studio environments. This transformative time revitalized Fishman’s interest in the grid, although Fishman is quick to point out that what she took away from her time with Martin was to approach the grid as a type of “breathing system,” closely related to her own daily practice of meditation, rather than anything purely structural.12 Such works from the early 1990s as Valles Marineris (1992), Mars (1992), and Sanctum Sanctorum (1992) demonstrate Fishman’s renewed approach to gridded compositions, all executed in darkly monochromatic tones. Many were exhibited in a solo exhibition with Robert Miller Gallery in 1993—at the time the highest- profile commercial exhibition of her work.

By the mid-1990s, another transformation in Fishman’s work started to unfold. In this new phase, Fishman integrated aspects of Chinese spiritual, philosophical, and cultural traditions into her practice. Although these traditions had intrigued Fishman at least since the 1970s, when she began her practice of Transcendental Meditation, they now were visually foregrounded, primarily evident in lively gestural marks echoing the flicks of the wrist of Chinese calligraphy. The results were some of the most sensational paintings of her career thus far. Fishman’s earlier gridded scaffolds melt and morph into calligraphic snippets or weblike skeins, skipping along the surface of her paintings, as in Blue Stallion (1997) or Night Shining White (1998)—each with its own distinctively vibrant palimpsest of sinewy ideogrammatic gestures. Suggestive of a private abstract language, these paintings further tease out the boundary between drawing and writing that Fishman first explored in her minimalist works decades earlier.

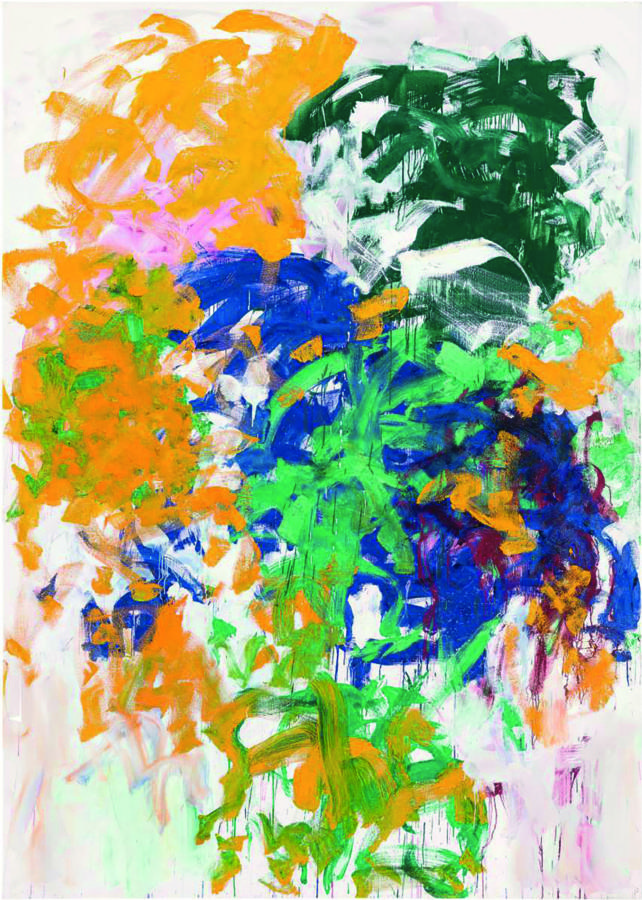

Joan Mitchell, Harm’s Way, 1987, oil on canvas, 111 × 79 3⁄4 inches, 281.9 × 202.6 cm

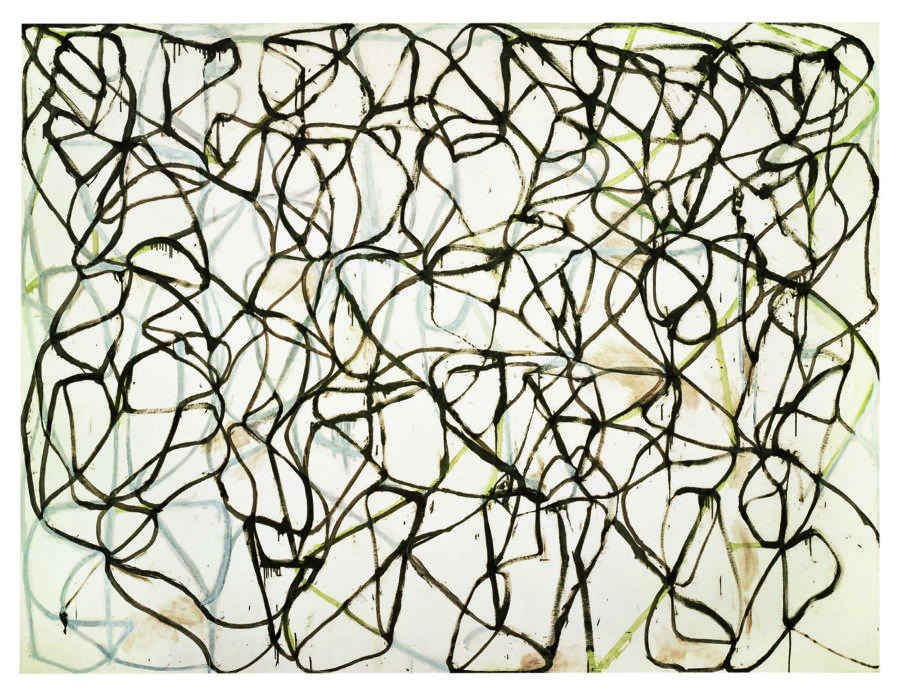

Soon after, in 1999, the artist broke up with her longtime partner of almost twenty-five years and started to live alone in her upstate studio, before moving back to New York full-time almost two years later— both major events that propelled her work further in new directions.13 Some paintings accentuated animated brushwork and dynamic surfaces, such as Copal (2000) and Double Glances (2001), which also recall the work of the late Joan Mitchell, who was an influence on, and friend to, Fishman later on in the senior artist’s life. Others possess more fiercely roving contours, as in The End of a Perfect Day (2002), The Fifth Path (2002), and Perilous Things (2003); or more extreme, labyrinthine allover compositions, as evident in Moon and Movies (2003) and Breaking and Entering (2005), whose meandering articulations conjure anthropomorphic associations as much as linguistic ones. In this regard, such paintings are in close dialogue with Brice Marden’s Cold Mountain and Attendant series of the 1980s and 1990s, which are filled with serpentine lines and inspired by similar points of departure. The undulating qualities of both Fishman’s and Marden’s work resonate with the intricate patterns of erosion found in the ancient Chinese scholars’ rocks both artists have long admired. Fishman, in fact, has assembled over the decades an extensive collection of these tabletop rocks, displaying them on numerous shelves throughout her home and studios. Unearthed from caves or lake bottoms, scholars’ rocks traditionally served as objects of contemplation for the Chinese ruling class thousands of years ago, as they were thought to be a way to bring the “mountain” inside where it could serve as a point of inspiration. While often resembling tiny microcosms of vast natural landscapes, these specimens were valued for their abstract, formal, convex and concave characteristics and frequently enhanced through carving and polishing to accentuate prized qualities such as thinness or openness. Fishman found this history\ particularly compelling, as these scholars’ rocks, with their origins dating back millennia, gave credence to the notion that the appreciation of artistic formal abstraction was actually an ancient phenomenon and not one fabricated in the mid-twentieth century in the West.14

Many of these paintings from the late 1990s and early 2000s are still among her very best, yet Fishman’s artistic style continued to evolve. Formal considerations are paramount to the artist, and she has described her ongoing drive to develop new painting methods and sensibilities as a conscious choice—wanting to ensure that her painting practice does not become rote and, as she says, to keep the challenge of painting alive and relevant for herself every day.15 Of course, this is a challenge she shares with many painters, who likewise are concerned that relying on past achievements or mastered techniques will present obstacles for moving forward.

So perhaps unsurprisingly, starting around 2008, change was again underfoot. Stylized glyphic lines are gradually replaced by new systems of rolling, smearing, and scratching, alongside renewed interest in casually gridded frameworks. A breathy spatial openness and illusory dimensionality recurs more frequently, manifested in paintings like Ristretto (2013), with its striking sense of gravitational suspension, or works like Namarupa (2014), with its forceful, chaotic energy, and alternating push-pull moments of translucency and opacity. Color, too, takes on new daring with vibrant, joyful combinations of confectionary pinks, luscious reds, and bright canary yellows which assume center stage in paintings like All Her Colors (2014), Margate (2015), and Bearer of the Rose (2017). With thickly arcing whites sparking color into action, the paintings recall again the buzzing brushwork of Mitchell, or perhaps de Kooning.

Brice Marden, Cold Mountain 6 (Bridge), 1989–91, oil on linen, 108 × 144 inches, 274.3 × 365.8 cm

A heightened sense of temporality and an unexpected lightness of bearing characterize the particularly compelling paintings of the last five years, many of which conjure the impression of being made in real time. Some are quietly lyrical, like the elegiacally spare Unbinding (2019), Traghetto (2019), or À la recherche (2018). À la recherche, most especially, projects the sense of “searching” or “longing for” of its title, with its evanescent impressions and wisps of ruby, cobalt, and misty gray shapes, emerging and receding amid the fog of untouched white gesso. Such gestures paradoxically seem at once both carefully calibrated and casually offhand. In reality, though, the painting is neither; rather, it is the result of a process whereby Fishman pressed one painted canvas surface onto another blank one to create a new, second painting that is an indexical trace of the first, a tactile residue akin to a “printed” mark. Intriguingly, such a maneuver also parallels strategies developed by a number of mid-career artists such as Jacqueline Humphries and Charline von Heyl, who combine gestural mark-making with quasi-mechanical stenciled or printed marks as part of their consciously staged engagements with expressionistic abstraction.

Other recent paintings occupy the opposite emotional register. Highvoltage, variegated endeavors, they include lively, interlacing trowel work, such as Too Much, Too Much (2020), or Choral Fantasy (2018), which, with its centrifugal explosion of scrapes, smudges, and swipes, is visually evocative of the sonic celebration the title suggests. A sense of speed, though, is perhaps best conveyed in Ballin’ the Jack (2019) which, at six feet high by seven feet long, is larger than the artist herself. The broad-scale marks imply a sense of the rapid movement of the artist’s hand and the full impact of her body, reinforced by the work’s title. Derived from an early-twentieth-century, vernacular expression, “ballin’ the jack” means going very fast or doing something very quickly.16 Such connotations are mirrored in the lateral, tilting swipes and diagonal bursts of black, grays, and greens that traverse the open expanse and anchor the energized field at its edges. “Ballin’ the jack,” though, can also be a gambling expression used to describe risking it all in one go. Going all-in. An apt description, too, of Fishman’s approach to painting.

Throughout the decades, Fishman has fiercely followed her own path, with little regard for the institutionally celebrated modes of art-making and dominant critical trends of the changing art scenes around her. Without perpetuating ideas about mythic grandeur and transcendence associated with mid-twentieth century Abstract Expressionism, Fishman’s searching engagement with abstraction offers up instead generously personal works that insist a language of gestural expressiveness can be made her own. And, while a critical inquiry into modernism has never been Fishman’s intention, her work suggests an eloquent undoing of past forms, disrupting fundamental assumptions of painting’s modernist legacies.

In this regard, Fishman is both an interesting precursor, and coincident force, in relation to a number of younger, often mid-career, female artists also grappling with how to push abstraction forward into new terrain, including Humphries, von Heyl, Jutta Koether, and Amy Sillman. These disparate painters, who often have been loosely grouped together with other peers under a broader rubric of “conceptual abstraction,” mine similar territory to Fishman’s, albeit from a different vantage. Their approaches, unlike Fishman’s, tend to hover on the cusp between irony and authenticity, borrowing historical aspects of abstraction and approaching “gesture” as a “readymade” to be appropriated for new purposes. Fishman’s lack of irony, though, does not diminish the position of resistance her paintings occupy in the world, which is similar to what these other painters achieve by other means. Koether, for example, often would (and still does) embed references to much older generations of male painters, such as Poussin, Manet, or C.zanne, in her own loosely figurative abstract paintings that make use of perceived feminine sensibilities evident in her flesh-pink and blood-red palettes as well as in her delicate, lacily rendered lines. Meanwhile, Sillman (whom Fishman has known since the late 1970s) often features psychically charged, cartoonlike renderings of figurative protagonists that frequently share pictorial space with gestural scrawls and geometric planes of electric hues or confectionary pastels, holding in tension discrete stylistic concepts within a single visual field.17 Koether and Sillman, like Fishman before them, transform the Abstract Expressionist legacies they mine, infusing that history with a consciously gendered approach to the expressive painted gesture.

Sillman, for her part, has also written thoughtfully about the gendered implications of Abstract Expressionism. As Sillman describes, Abstract Expressionism, though conventionally coded as “mythically straight and male in quotation marks,” has in recent years become appealing for many women and queer artists, who, as Sillman says, “are recomplicating the terrain of gestural, messy, physical, chromatic, embodied handmade practices.”18 Such an assertion gibes in interesting ways with Fishman’s own choices at the start of her creative journey, when she found herself drawn to Abstract Expressionist painters as “rogues, outside the normal course of things,” who inhabited a “hidden language” that seemed “an appropriate language for me as a queer.”19 Both Fishman’s earlier reactions and Sillman’s more recent written remarks make a similar point: despite Abstract Expressionism’s historicization to date as the ultimate “macho” genre of twentieth-century art, it was also a mode of artistic expression that was (and is) intrinsically inviting to many marginalized artists.

Curator and critic Helen Molesworth has commented on the difficulty of the category of “feminist abstract painting,” noting that works that are both abstract and feminist often “suffer from a kind of illegibility.” 20 Although the genre of formal abstraction, she explains, with its nonrepresentational qualities, historically seemed to be the most likely avenue for the work of woman artists to transcend gendered receptions, the engrained systems around such work—made up of the critics, curators, and collectors—have not been “so willing to operate in a state of genderless suspension,” invested as they have been, and are, in the status quo. Whether consciously or not, such systems have continued to inscribe abstraction in “a field of gendered language.”21 While the situation has been starting to shift lately, especially since Molesworth penned this essay back in 2007, the crux of her argument remains true: feminist abstract painters’ work is “still radically difficult to account for or narrate, so much so that the paintings have yet to find their rightful place on the walls of permanent-collection galleries of that other great institution of modernity: the art museum.”22

Part of this “illegibility” to which Molesworth alludes certainly applies to Fishman and her work. For while Fishman has had, particularly since the mid-1990s, solo exhibitions at a number of prestigious commercial galleries, and, moreover, was the subject of an outstanding 2016 retrospective at the Neuberger Museum of Art at SUNY Purchase, the fact remains that her paintings are still missing from most of the preeminent museum collections in America. Hopefully, as specific myths of art historical discourse around modernism continue to be dismantled, newer perspectives will better account for Fishman’s formidable career. Such vantages, too, are more likely to reflect how shifts in art-making actually transpire, which is to say not in a precisely linear order, but rather along overlapping vectors of creative influence, as concepts circle around and repeat, or intersect at tangential angles.23 Meanwhile, as the art world grapples to catch up to her, Fishman continues to paint, as she always does—each day approaching the canvas anew and facing abstraction and all of its histories not as an exhausting dilemma to negotiate, but as inspirational fuel to energize her embrace of unexplored challenges, guided steadfastly along the way by her boundless fortitude, through six decades and counting …