April 2020

Packed into the space of four by six inches, Louise Fishman’s recent watercolors deliver the same graphic punch and material splendor of her larger oil on linen paintings. As fellow painter Suzan Frecon has perceptively written about Fishman’s work, “dense heavy impastos interweave with faint and delicate touches. One can perhaps think of musical dimensions while trying to describe them.” 1 In ways that hardly seem possible for this humble medium, Fishman deftly commingles casual ochre washes with thick, heavily textured passages of steely blues and dark greens, occasionally interspersed with smoldering patches of crimson to set the tiny sheets ablaze (Fig. 1).

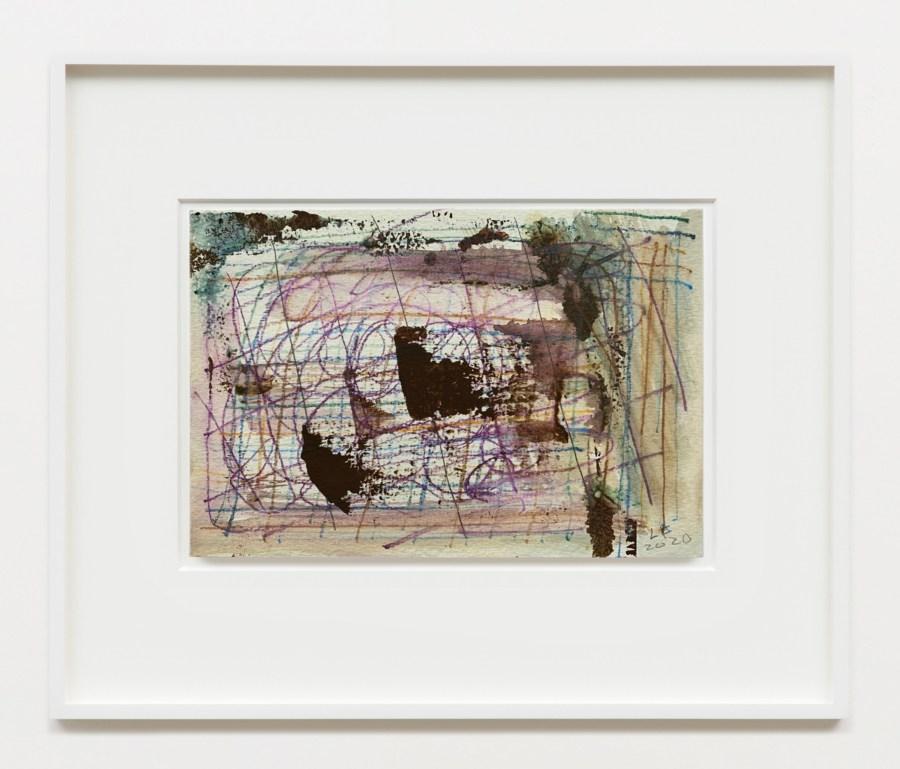

Like other painters of her generation, notably the late Jack Whitten, Fishman dissolves and humanizes the minimalist grid, merging order with spontaneity, plan with accident. As Fishman wrote in 1977, “I try to take the painting by surprise. I begin as if accidentally (although all the while I have been sneaking glances at the work).” 2 This motivation is evident in works like Untitled (2020) (Fig. 2): with its subtle evocations to a musical score, its irregular, off-kilter grid tries in vain to restrain vigorous swirls of magenta, phthalo green, and manganese blue underneath. The whole composition is punctuated by the assertive finality of a few quick, gestural notes of burnt sienna on top.

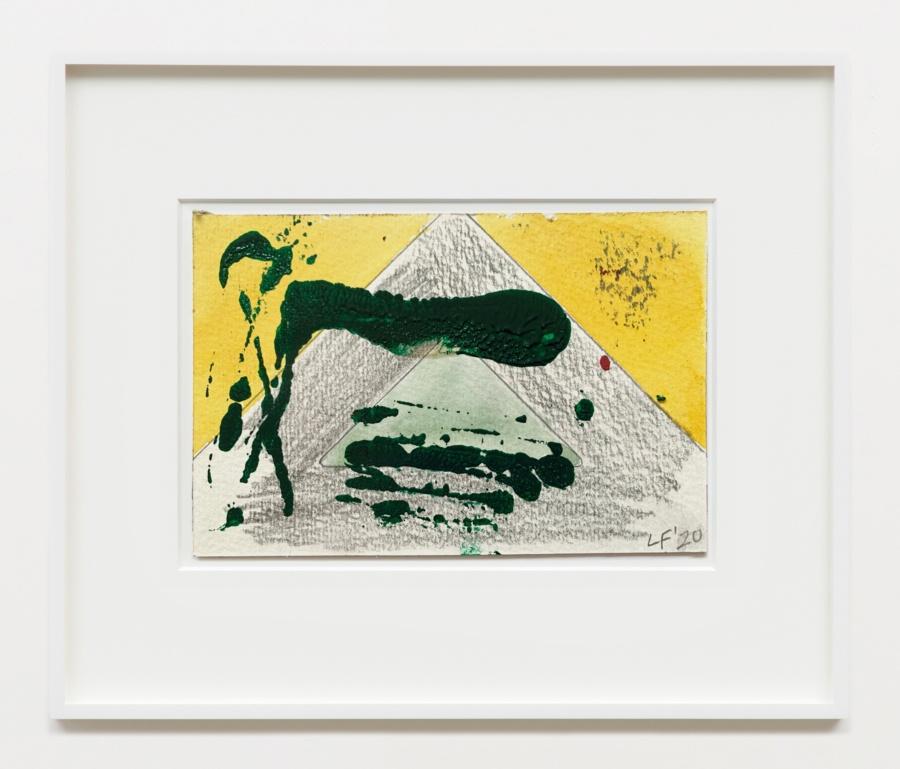

Having freed herself from the often prescriptive dogmas of the 1960s about modernist painting and abstraction, Fishman forged a highly personalized, process- based practice. She was loosely aligned with a group of artists imperfectly labeled “postminimalist” by art historian and critic Robert Pincus-Witten in the early-1970s. Works which at first seem like homages to hard-edge predecessors like Robert Mangold or Ellsworth Kelly (Figs. 3 and 4) either find themselves stained with thick globs of dark paint, or are playfully irreverent with their meandering lines and casual washes in their refusal to be hemmed in by established geometries.

For those familiar with Fishman’s work, her material subtlety and sophistication come as no surprise. Since the 1970s, Fishman has forged a singular practice informed both by her identity as a lesbian and by her passion for modern art and techniques. Fishman confidently proclaimed in 1977 that, “If good painting is what you want to do, then good painting is what you must look at. Take what you want and leave the dreck.” 3 For Fishman, this meant taking the relevant bits from Paul Cézanne or Willem de Kooning, as much as from Agnes Martin or Eva Hesse. The pursuit of individual freedom and personal expression was and remains her primary motivation as an artist.

Fishman, discussing the positive impact of Hesse’s work on her practice in the early 1970s, reveals that, “At that moment, I decided I could do anything I wanted to as an artist, use any material I wanted, make sculpture, etc. Limitations were off.” 4 For Louise Fishman, as with Eva Hesse, art making was not a zero-sum proposition, pitting one’s politics or identity against formalism or aesthetics. There was a way to have your cake and eat it too. Through materiality, these two artists explored aspects of their human physicality, aestheticizing both in the process. Fishman’s watercolors partake of the same physicality characteristic of her early multi-media constructions as well as her more recent large-scale paintings.

Some of Fishman’s new watercolors seem archeological or even geological, as sedimentary layers compacted with stony fragments from long ago civilizations (Fig. 5). Others evoke comparison to the desiccated puddles from which primordial lifeforms first crawled from water onto land (Figs. 6,7). As critic and poet John Yau has written about her work, “Fishman replaces illusionistic space with a layered space, one which has been scraped, dug up, and partially covered over. If the body analogy holds in her paintings…it is because she has connected the body to the earth and ultimately to history and its repeated conflicts and conflagrations.” 5

Fishman’s watercolors, much like her paintings, are not works “about” various aspects of her layered history and identity, but rather personal expressions of her embodied experience as someone fully living life. As art historian Richard Shiff has recently written about Eva Hesse, “Rather than referential significance, Hesse’s mark had life. Whose life? What life? An artist’s mark is a go-between, figuring the life of the paper as well as the life of the person.” 6

Although intimate in size, Fishman’s watercolors are palpable indices of this very same dual-figuration merging both figure with ground and art with life and seduce even reticent viewers to take a closer look. At what point does vision yield to something more like remote touch? Without giving a definite answer, the watercolors pose this question wordlessly, purely through their sensory play of colors and textures on paper.

Fig 1. Louise Fishman, Untitled, 2020, watercolor and pencil on paper, 4 × 6 inches; 7 × 9 inches (framed)

Fig 2. Louise Fishman, Untitled, 2020, watercolor, color pencil, and pencil on paper, 6 × 9 inches; 9 × 12 inches (framed)

Figure 3. Louise Fishman, Untitled, 2020, watercolor, pencil, and acrylic on paper, 4 × 6 inches; 7 × 9 inches (framed)

Figure 4. Louise Fishman, Untitled, 2020, watercolor and pencil on paper, 4 × 6 inches; 7 × 9 inches (framed)

Figure 5. Louise Fishman, Untitled, 2020, watercolor, ink, and pencil on paper, 4 × 6 inches; 7 × 9 inches (framed)

Figure 6. Louise Fishman, Untitled, 2020, watercolor on paper, 4 × 6 inches; 7 × 9 inches (framed)

Figure 7. Louise Fishman, Untitled, 2020, watercolor on paper, 4 × 6 inches; 7 × 9 inches (framed)

(1) Suzan Frecon, “Traveling in Louise Fishman Terrain,” in Turps Banana, Issue 17 (January 2017): p. 40.

(2) Louise Fishman, “How I Do It: Cautionary Advice from a Lesbian Painter,” in Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics, Issue No. 3 (Fall 1977): 74.

(3) Ibid.

(4) Louise Fishman with Inge Pett, “‘Always Wild at Heart’—An Interview with Louise Fishman,” Yeast—Art of Sharing, February 17, 2017.http://www.yeast-art-of-sharing.de/kunst/always-wild-at-heart-an-interview-with- louise-fishman.

(5) John Yau, “Why There Are Great Women Artists,” in Louise Fishman. New York: Cheim & Read, 2000, n.p. (6) Richard Shiff, “To Draw Is To Ground,” in Edouard Kopp, John Elderfield, Richard Shiff, Terry Winters