September 10, 2016

Louise Fishman

Prestel, New York, 2016.

According to conventional wisdom, in the 1940s and 1950s a group of male painters living in New York and working in a heroic style on a monumental scale essentially cornered the market on gestural abstraction. If that’s true then it raises the question: What’s left for an artist to express after the triumph of Abstract Expressionism? And what, if anything, could a woman contribute to the territory so decisively demarcated by Jackson Pollock’s ejaculatory drips, Willem de Kooning’s fractured women, and Franz Kline’s bold, black strokes (fig. 1)? American painter Louise Fishman’s powerful body of work offers a robust response. Both embracing and redefining the aggressively masculine tradition of Abstract Expressionism, she has employed its formal language to create large scale, gestural abstractions that share the physicality, dynamism, and emotional force of that movement while remaining visually poetic and intimate in tone. As critic Michael Brenson has noted, Fishman’s work is “tough without being macho, . . . modest, no matter how grand the aim.” Fishman herself observes, “I’ve always thought of myself as an Expressionist painter. I associate it with a certain kind of passion and a certain kind of marking. A kind of immediacy.” The artist seems to revel in the act of painting; in the materiality of oil paint roughly applied by brush, palette knife, or serrated trowel; in the texture of densely built up and scraped down surfaces; in the agile, sweeping gesture. Over the course of a career spanning more than fifty years she has used these tools and techniques to create works that express a broad range of emotions, from explosive anger and profound mourning to, more recently, joyful exuberance. Her work seems to pulsate with life.

Franz Kline (1910–1962), New York, N.Y., 1953, Oil on canvas, 79 × 50½ in. (200.6 × 128.2 cm) Albright Knox Gallery, Buffalo, Gift of Seymour H. Knox, Jr., 1956

Fishman has enduring respect for the Abstract Expressionists and cites them as among her greatest influences. She is not the only woman to lay claim to this male dominated tradition but, unlike other well known female practitioners of this style, such as Lee Krasner and Joan Mitchell (fig. 2), she approaches this gendered form of painting as an active feminist and a lesbian. Speaking of abstraction’s appeal, Fishman has recalled, “painting gave me the same feeling of tremendous freedom I had experienced playing ball” as a tomboy in school. She explains: “I was an abstract painter from the start and it was abstraction as much as painting that thrilled me. . . . I saw all those painters [the Abstract Expressionists] as rogues, outside the normal course of things. I knew by the time I got to art school that I was a lesbian. . . . I felt that abstract expressionist work was an appropriate language for me as a queer. It was a hidden language, on the radical fringe, a language appropriate to being separate. In sports I didn’t have to explain myself. And in art I didn’t have to unless I used figurative art and content. And like baseball, painting was a powerful activity that didn’t narrowly define me.”3 It seems that Fishman identified with Abstract Expressionism as a means by which to both express and protect herself as a young artist in the 1950s. It was a choice that served her well, and since the late 1990s she has taken this style of painting to new heights.

Figure 2. Joan Mitchell (1925–1992), Ladybug, 1957, Oil on canvas, 77⅞ × 108 in. (197.8 × 274.3 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York

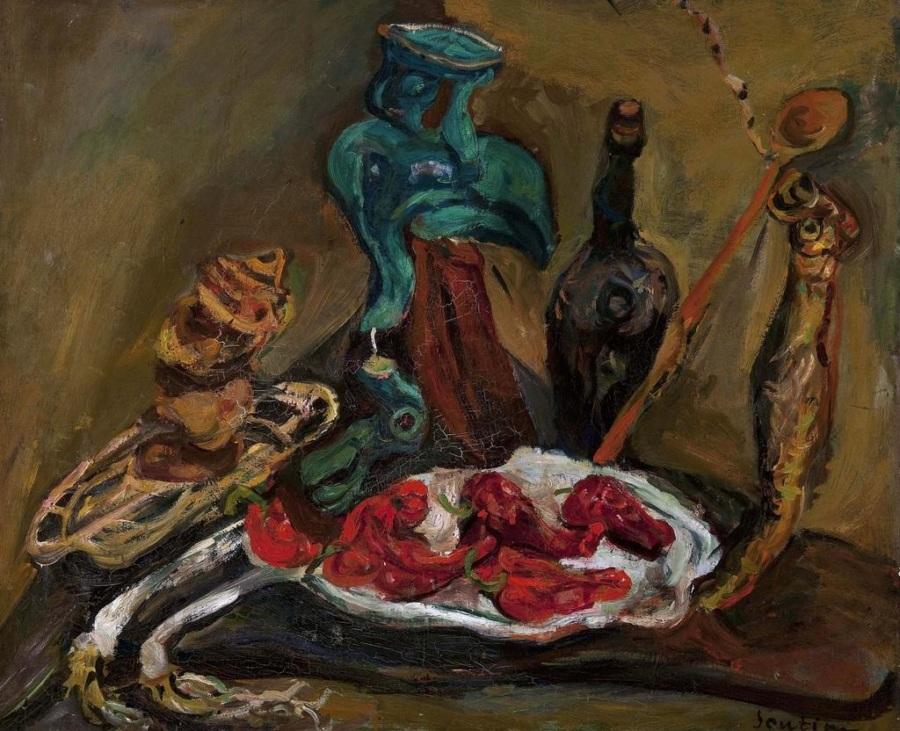

Louise Fishman was born in Philadelphia in 1939 and grew up with two practicing women artists. Both her mother, Gertrude Fisher Fishman, and her paternal aunt, Razel Kapustin, studied at the Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania, where they had access to the work of European Modernists such as Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Chaim Soutine, and Georges Rouault. Her mother was an abstract painter whose sophisticated, richly colored works particularly reflect the influence of Matisse. Fishman’s aunt, a Social Realist painter, briefly studied in New York with Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros; Jackson Pollock was among her classmates. She later turned to Jewish themes as her main subjects and maintained an active professional life. As a young girl Fishman spent time in her mother’s library, poring over artists’ monographs published by the Barnes; reading catalogues her parents had received from the Museum of Modern Art, New York, as a membership benefit; and leafing through issues of ARTnews. She was always looking at images but had not yet resolved to become an artist.4

Figure 3. Louise Fishman, Untitled, 1968 Gouache and graphic on paper, 17½ × 19 in. (44.5 × 48.3 cm)

Fishman entered art school in 1956, attending the Philadelphia College of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and the Tyler School of Fine Arts, where she earned Bachelor of Fine Arts and Bachelor of Science degrees in 1963. At Tyler, which she describes as “a real academy,” she learned oil painting techniques and created still lifes and figure paintings from live models. Although she felt some frustration in this conservative setting, she valued the rigorous training she received from the Tyler faculty and ascribes her respect for traditional materials and methods in part to them. In 1965 Fishman received a Master of Fine Arts degree from the University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign, then hopped in her Nash Rambler and drove straight to New York City.

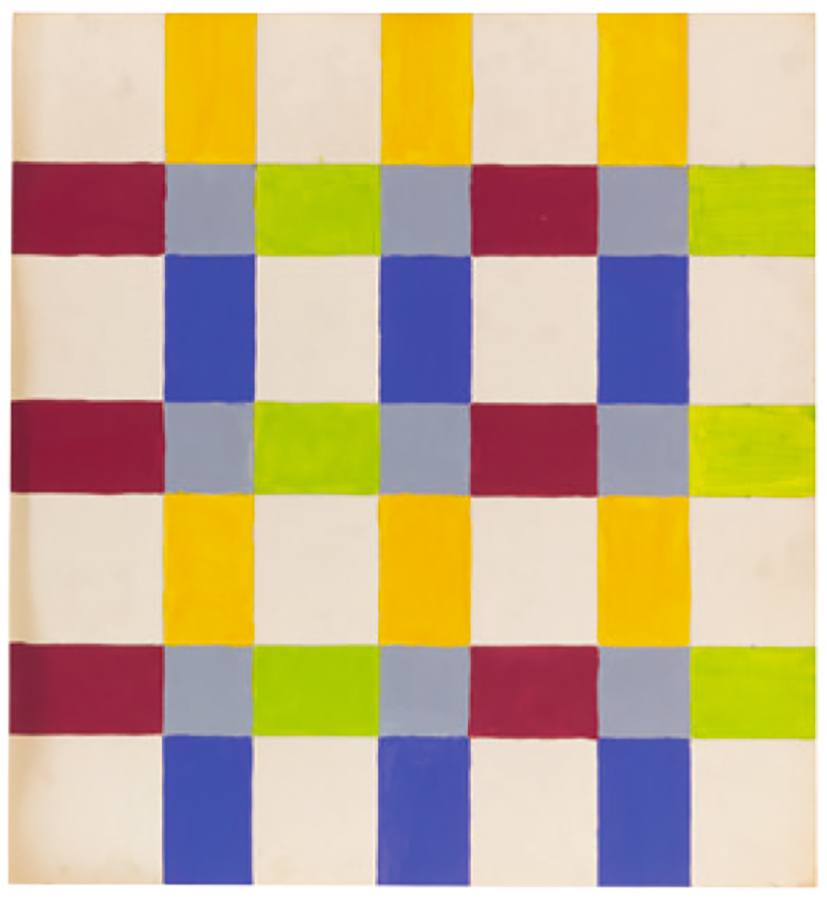

The 1960s was a time of great social, political, and cultural upheaval, and New York was the place to be. Fishman quickly became involved with the emerging women’s liberation movement, as well as with the movement for lesbian and gay rights, and attended consciousness raising sessions organized by the radical feminist group known as Redstockings along with meetings of Upper West Side W.I.T.C.H. (Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell). While feminism raised her awareness and inspired her activism, it was the advent of lesbian feminism that changed her life. As she recently declared, “I knew I was home! I felt like I was walking in my own shoes for the first time.”5 This realization prompted her to question the impact of “all the male stuff in my history” and to make major changes in her art.6 By the late 1960s Minimalism had eclipsed Abstract Expressionism as the dominant mode of art making, and for about six years, from 1964–70, Fishman followed suit, making a series of hard edged grid paintings inspired by the work of Sol LeWitt and Ellsworth Kelly (see fig. 3). From this point on, the grid became a constant in her work. Then, in an attempt to eliminate all references to the prevailing male dominated styles from her art, she abandoned painting altogether and began experimenting with materials and techniques traditionally associated with women, craft, and the handmade. Fishman cut up her canvases and wove or stitched the squares together with thread, creating small scale, quilt like, gridded collages (see pl. 6). She admired the work of Eva Hesse, whose organic sculptures made of malleable materials such as latex and rubber breathed life into Minimalism’s geometric forms. Following this example, Fishman relaxed her compositions and broadened her range of materials, even adopting the use of liquid rubber. She continued to use the grid, but it was now the scaffold for a more personal, intimate form of expression.

From 1970 to 1974 Fishman belonged to a consciousness raising group that included artists Harmony Hammond, Patsy Norvell, and Jenny Snider; dancer Trisha Brown; and anthropologist Esther Newton, among others. They met weekly in SoHo, the new center of the downtown art scene, to talk about their work in the context of feminism. They began these sessions by choosing a topic, such as the challenges facing women artists in a male dominated culture, and each member of the group then addressed the subject based on her own experience. For Fishman, strong feelings emerged during these meetings, including a deep seated sense of both personal and collective rage. It was a moment of crisis. As Fishman’s spouse, graphic designer Ingrid Nyeboe, recalls: “It wasn’t just about a lack of recognition. It was the knowledge that in the seventies women really were second class citizens. The rage level for both straight and lesbian women was so thick you could cut it with a knife. The fact that you knew your life had been adjunct to the culture was unbearable. Your contribution went unacknowledged. What had I accomplished, what had my mother and grandmothers accomplished? It’s like ripping yourself apart and putting yourself back together again.”7

Figure 4. Louise Fishman, Angry Louise, 1973, Acrylic on paper, 26 × 40 in. (66 × 101.6 cm) Pl. 12

Fishman’s rage provided the fuel for a series of works that were her most personal to date. The Angry Paintings of 1973 were unlike anything she had done before, and their ferocity frightened her. She spontaneously scrawled “Angry Louise” on a sheet of paper, surrounded the words with agitated slashes of green on a blood red ground, and finished with the inscription “Serious Rage” (fig. 4). Expressing her anger on paper proved to be a transformative experience; Fishman believed she might never again return to abstract painting. She followed Angry Louise with a series of works intended to capture the anger felt by various members of her consciousness raising group, by her mother and aunt, and by art world acquaintances, noted feminists and literary figures, and other women she admired. This impassioned sorority included Angry Harmony (for Hammond), Angry Gertrude (for her mother and Gertude Stein), Angry Razel (for her aunt), Angry Paula (for gallerist Paula Cooper), and Angry Marilyn (for her heroine, the iconic actress Marilyn Monroe). All told there are thirty of these emphatic works, each bristling with explosive energy (see pls. 9–17). Despite her concerns about where they might lead, these portraits ultimately brought Fishman back to painting.8

Although it took nearly five years for Fishman to return to the medium that had been her first love, when she did so she made a total commitment, one that has lasted nearly forty years. She at first worked in oil on linen, applying paint thickly with a palette knife to achieve a highly tactile, almost sculptural effect. As she remarked shortly after returning to painting: “I thought of [the paint] like clay. . . . I was trying to make paintings that felt like objects.”9 And although their subject matter is not overt, Fishman’s densely painted, small scale abstractions of the late 1970s to early 1980s are instilled with meaning. Around the time they were completed, Fishman, though not religious, had become interested in exploring her Jewish roots and identity. She studied Yiddish, read Jewish history and literature (including Elie Wiesel’s Holocaust memoir and texts on mystical Judaism), and gave her works titles that reference Jewish folklore, such as Golem (pl. 28) and Tabernacle. According to the artist, Ashkenazi (pl. 26), a bold, symmetrical composition in black, white, and red, is intended to resemble an altar flanked by candles.

In 1987 Fishman bought a farmhouse in upstate New York that continues to serve as a studio and second home. This new residence had a salutary effect on her life and work. After she settled there her paintings began to echo the natural environment in its various forms and phenomena, recalling, as Jill Weinberg and Bernard Lennon have noted, “earth, rocks and stones, water, trees, the light in the woods and the space of the fields.”10 Headwaters (pl. 35), a tightly composed, compact painting built of thick, tumbling slabs of green, orange, black, and white, captures the force of a waterfall breaking over bedrock. In contrast, Stand of Beech (pl. 36), a thinly painted grid of whitish grey, turquoise, and pink rectangles, seems bathed in an otherworldly glow evoking moonlight in the trees. In fact, Fishman’s paintings tend to gravitate between two poles: alternating between gesture and geometry, they may be earthy or ethereal, intensely physical or quietly spiritual.11

In a career typified by experimentation and change, Fishman’s next body of work constituted a striking formal departure along with a return to lifelong interests. In the spring of 1988 she traveled to Eastern Europe accompanied by a friend who was an artist, collector, and Holocaust survivor. They visited the region’s major cities, including Warsaw, Budapest, and Prague, as well as the sites of the former Nazi extermination camps at Auschwitz and Terezín. The experience affected Fishman profoundly and, upon her return, she created a group of nineteen elegiac paintings collectively titled Remembrance and Renewal. They are spare, rectilinear compositions in subtle shades of dark blue, green, and black paint applied in thin washes with broad strokes. Fishman’s luminous, hovering blocks of color and deeply somber palette recall Mark Rothko’s late work as well as his memorable statement, issued with Adolph Gottlieb, that subject matter is valid only if it is “tragic and timeless.”12 The surfaces of these mournful paintings are layered but smooth, with just the slightest traces of texture provided by the handful of silt laced with human remains that she gathered from the Pond of Living Ashes at Auschwitz and applied to these canvases in a coating of beeswax combined with layers of thinned paint. After visiting the concentration camps she had questioned whether the act of painting could ever hold any meaning, but as she recalls, “when I used the wax and ashes it felt like I had company in the studio. I had these voices with me and I could paint.”13 In a spirit of renewal she gave the paintings Hebrew titles that refer to Passover, a holiday commemorating the emancipation of the Israelites from slavery in ancient Egypt and the reaffirmation of their faith. For example, Haggadah (pl. 40) is named for the traditional book of prayers and rituals for the Passover Seder, while Bitter Herb (fig. 5) refers to one of the symbolic foods consumed at that meal. Taken together, the Remembrance and Renewal paintings serve as a memorial to the many who were lost and as a testament to the endurance of those who survived. As a body of work it is at once wholly material and oddly transcendent. Fishman faced another crisis in 1990, when her studio in upstate New York was destroyed by fire and some of her works—as well as all of her tools and equipment—were lost. She developed chronic fatigue syndrome as a result of the trauma and found herself unable to paint. In an effort to recover her health and regain her focus she traveled to New Mexico, where she spent time with painter Agnes Martin. She was inspired by the artist’s serene grid paintings and quiet presence, and she realized that for Martin the grid was more than a simple compositional device, it was a form of meditation. This notion resonated with Fishman, who had practiced Buddhist meditation on a daily basis for years. She decided to return to the grid as a tool for balancing structure and spontaneity in her art. Fishman began to paint with renewed strength and confidence, creating large scale, vertically oriented works such as Sanctum Sanctorum and Valles Marineris (both 1992; pls. 48, 49), a canvas painted primarily with a roller that features shimmering blocks of pale green framed by a gray black grid that alternately suggests flatness and depth.14

Figure 5. Louise Fishman, Bitter Herb, 1988, Oil on linen, 65 × 45 in. (165.1 × 114.3 cm) Courtesy of Fernando Luis Alvarez Gallery, Stamford, Connecticut Pl. 38

Fishman first became aware of the importance of the picture plane—the extreme foreground or point of visual contact between the picture and viewer—and the grid’s potential as a flattening device in Karl Sherman’s design class at the Philadelphia College of Art in the mid 1950s. Sherman encouraged his students to focus on the dynamics of the canvas as a whole. He believed that different points in a painting’s rectangular surface contain different energy levels, with some areas highly active and others inert. Fishman absorbed these ideas and later observed of her process: “As I make a mark I am aware of the impact on every square inch of the painting.”15 For the artist, composition became a sort of dance on the surface of the canvas as she recorded her movements with each mark.

Fishman’s increasingly ambitious works of the 1990s display a vigorous physicality that is expressed, in part, through a lively interplay between gesture and grid. The dazzling Blonde Ambition (1995; pl. 52), a boldly graphic, black and white painting whose composition Fishman describes as a collapsing grid, captures the look and vitality of a signature Franz Kline but is inspired by a far different source. Fishman watched Madonna’s 1990 Blond Ambition World Tour on television and immediately identified with the pop icon in her athleticism and her toughness. She recalls: “I saw this little Tom Boy dancing around and thought ‘she’s like me!’ ”16 Madonna also emulated Marilyn Monroe, who is the other blond in the painting. In this work a stark white grid veers diagonally toward the left, resembling a figure with arms outstretched and head tossed backward; the gritty white paint, textured with sand, is as thick as plaster.

The radiant For There She Was and The Sunrise Ruby (pls. 65, 67) are densely painted, tactile works whose surfaces have been built up, scraped down, and built up again in a process the artist likens to an “archaeological dig.”17 Both canvases are nearly square in format, their gestural brushstrokes aligned with rectilinear grids. Here Fishman’s palette, newly colorful, comprises glowing yellows and reds and rich earth tones that seem to spring from natural forms and forces. Although more of the land than of the sea, these works evoke the luminous, nearly abstract seascapes of British painter J. M. W. Turner, a connection that deepens in Fishman’s more recent paintings, as will be discussed below. Perhaps more significantly, they point to Fishman’s wholehearted embrace of the postwar American tradition of large scale gestural abstraction, which, by the time these canvases were painted, in the late 1990s, she had begun to make her own.

Although Fishman may be best known for a highly physical painting process that produces gestural, expressive marks that follow the movement and extension of her body, she has also, since 1997, worked with calligraphic markings to chart what she calls the “language of the hand.”18 Her interest in such forms derived in part from a study of Hebrew characters and Chinese and Japanese calligraphy, which she admires as much for their aesthetics as for the meanings they convey. Of course, the impact of Pollock’s, Mark Tobey’s, and Bradley Walker Tomlin’s sinuous lines cannot be ignored. Not surprisingly, the calligraphic mark first appeared in Fishman’s drawings, later joining gesture and the grid as structural elements for her paintings. In Paul’s Hands (pl. 72), made in memory of the late writer and translator Paul Schmidt, features an interweaving of radiant yellow and green calligraphic strokes that creates an amplified sense of movement within the grid. And in Slippery Slope (pl. 92) a network of fluid black lines graces a field of Prussian blue.

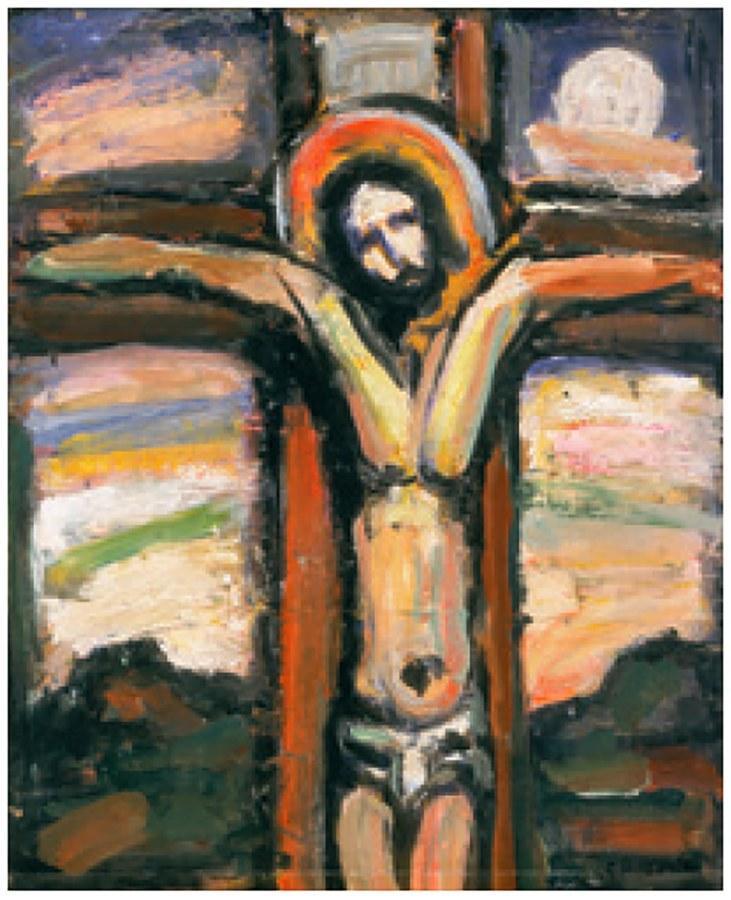

Fishman is aware of a shared “quality of expression” across the work of the artists who have most greatly impacted her. Her sources include the canvases of modernists such as Rouault, Soutine, Kline, and Alberto Giacometti and nineteenth and mid twentieth century American poetry (figs. 6, 7). In The Art of Losing (pl. 79), a large scale, brooding work named for a poem by Elizabeth Bishop and dedicated to a lost love, a grid constructed of thick black bands drips down a translucent blue white plane, giving the impression that, as critic Faye Hirsch puts it, “the whole painting is weeping.”19 The heavy black contours and cool, glowing light suggest stained glass and recall the work of Rouault and Soutine, as well as that of De Stijl artist Piet Mondrian, whose work Fishman had the opportunity to view at the Barnes Foundation and the Philadelphia Museum of Art when she was a student. Notably, Fishman has also looked farther afield, drawing inspiration from medieval crucifixes and religious masterworks such as Rogier van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross (ca. 1435) and Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece (1512–16). Like these works, her paintings can be very sculptural. Zero at the Bone (pl. 99), for example, is a dense composition of thickly applied bands of earth and mineral colors whose materiality is palpable. It is a powerful work in the Abstract Expressionist mode whose “vitality stems from an appreciation of European culture merged with American spontaneity and force,” according to critic Jonathan Goodman.20 As in The Art of Losing, this painting is inspired by poetry as well as the history of art. The phrase “zero at the bone,” the last line of a poem by Emily Dickinson, describes an intense sensation akin to a chilling fear.

Figure 6. George Rouault (1871–1958), Christ, ca. 1938 Oil on canvas, 19⅜ × 15⅞ in. (49.2 × 40.3 cm) Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Samuel S. White III and Vera White Collection, 1967

Figure 7. Chaim Soutine (1893–1943), Fish, Peppers, Onions (Poissons, poivres et oignons), ca. 1919 Oil on canvas, 23⅝ × 2815⁄16 in. (60 × 73.5 cm) The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, BF2042

Fishman’s new work took an exhilarating turn after she traveled in fall 2011 to Venice, where she spent two months as artist in residence at the Emily Harvey Foundation. During her stay she took hundreds of photographs and painted numerous small watercolors. She was inspired by the color, light, and atmosphere of the city, with its ubiquitous waters and luminous blue skies. Naturally, she sought out the work of the great Venetian painters such as Titian, Tintoretto, Giorgione, and Veronese, and she has likened the thrill of walking in their footsteps to the experience of traversing “sacred ground.”21 Fishman made this journey with Nyeboe, who was then her new love and six months later would become her spouse. It was a creatively rich and personally fulfilling time.

Fishman returned to her New York studio and immediately began making paintings that were based on the Venice watercolors yet quite different in their materials, scale, and impact. She describes the new works as having an “odd theatricality about them . . . this quality of everything moving up and out, explosively,” a condition she sees as a direct response to Titian’s Assumption of the Virgin (fig. 8).22 Serenissima (pl. 105) is titled for the name Venice bore for more than one thousand years as a city state; it translates as “most serene republic.” Paradoxically, it is a highly dynamic work in which all parts appear to be in perpetual motion, broad stokes of paint radiating from the center of the canvas with amazing force. By contrast, Crossing the Rubicon (pl. 102), which is named for Julius Caesar’s proverbial point of no return, is animated by vibrant slashes of color that appear to gravitate toward the middle of the composition and spin. Unlike her earlier, densely painted and composed canvases, Fishman’s Venetian works appear to open up and let in air and light, breathing new life into her art.

Figure 8. Titian (Tiziano Vecellio; ca. 1488–1576), The Assumption of the Virgin, 1516–18, Oil on panel, 270 × 140 in. (685.8 × 355.6 cm) Chiesa di Santa Maria dei Frari, Venice

And then there are the blues in these works—the phthalos, ultramarines, and related tones, occasionally interrupted by blazing bands of red. Although Fishman had used blue before, the vibrant hues of her Venetian paintings are something new. Filled with allusions to the Italian city, they echo the brilliant shades of Titian, the iridescence of a Murano glass vase, the sky, and the Venetian Lagoon and the reflections in its waters. Fishman has said that in Venice the air itself feels as if it’s colored.23 In addition, there is a play among the blues in these works that suggests the dancing of light on all surfaces. But despite their ethereal blend of color and light, these large scale gestural abstractions retain the physicality, grandeur, and emotional punch that mark the best of the Abstract Expressionist tradition, qualities Fishman continues to pursue in her most recent work.

Figure 9. Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851), Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth, exhibited 1842, 36 × 48 in. (91.4 × 121.9 cm) Tate Gallery, London

Figure 10. Louise Fishman, For There She Was, 1998, Oil on linen, 76¼ × 82 in. (193.7 × 208.3 cm) Collection of Romita Shetty and Nasser Ahmad Pl. 65

There was another shift in Fishman’s work after she went to London in fall 2014 for the opening of an exhibition of her Venice watercolors. While there she had the chance to see several important museum shows, including presentations of the late works of Rembrandt and Turner at the National Gallery and at Tate Britain (fig. 9), respectively, and an installation of John Constable’s paintings at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Though each artist made a strong impression she felt a special kinship with Turner, who is known for his views of Venice. Margate (2015, pl. 114) is Fishman’s homage to the British master, who studied and painted in Margate, Kent, a seaside town to which he returned throughout his life. In this work a small slash of red is tossed about by churning stokes of blue, green, and white, recalling Turner’s portrayals of natural phenomena such as light, rain, and wind in scenes of ships battered by stormy seas in a manner also reminiscent of For There She Was (fig. 10) and The Sunrise Ruby, Fishman’s works from the late 1990s mentioned above. Yet in Margate the affinity goes further, as Fishman captures the intensity of a Turner seascape and, remarkably, distills it to its essence. Likewise, in Kreisleriana (pl. 113), a celebratory work named for a piano composition by Robert Schumann and dedicated to his fellow Romantic composer Frédéric Chopin, Fishman captures the substance of gestural abstraction with a few broad, raw, vertical strokes of bold color. Over the course of a career spanning more than five decades she has fully mastered these and other masters of the arts, interpreting their work through the lens of her own experience.

Although Fishman has successfully worked within the largely masculine idiom of Abstract Expressionism and acknowledges a debt to a number of major male artists from the Renaissance through Modernism, her work is most profoundly shaped by the fact of having come of age as a woman artist in the 1960s and 1970s. That was a time when feminism made significant inroads into the social consciousness and, in terms of art, opened the door to a wide ranging pluralism, seen in works that explore multiple materials, styles, subjects, and ideas. In a long career marked by both experimentation and consistency, Fishman pushed formalist abstraction beyond the standard notions of purity and universality that defined much modernist art. One of her great contributions, along with peers such as Elizabeth Murray, Mary Heilmann, Suzan Frecon, and Pat Steir, has been her determination to introduce content into this traditionally male bastion and make room for firsthand experience and personal expression.24 While Fishman’s paintings do not openly tell the story of her life, they arise from her personal, political, and cultural experiences to form a body of work that offers deep aesthetic rewards while both redefining and expanding the scope of abstraction.