November 5, 2020

Louise Fishman published by Karma, New York, 2020

Download as PDF

Louise Fishman is available here.

Louise Fishman handles paint with intention, energy, and feeling. Her work is robust. For over six decades, she has smeared, dragged, trowelled,and brushed oily pigments across supports of many shapes and sizes. Since the 1950s, Fishman has made hundreds of abstract paintings. She has also periodically steered her gestural strokes into legible words and phrases. Evocative titling and compelling stories have leant additional meaning to her artistic output, as has her identity as a queer, lesbian, feminist, Jewish woman. Yet despite the rich materiality and vivid life experiences that permeate her practice, Fishman’s paintings rarely yield to her biography. It’s as if the painted object and the life beyond its edges can’t be in focus at once. This refusal confers power to Fishman’s paintings—they operate on their own terms. But refusal also creates frustration. And for me, it’s the frustration of Fishman’s work that keeps me returning to it.

Fishman’s studio is on the seventh floor of an arts building in Chelsea, a neighborhood that has become exponentially more expensive over the last twenty years. It was in the nineties that she first moved in to her current studio building, the same decade I arrived in New York City to attend art school. In a recent conversation, Louise told me that she still sometimes trawls her block for new painting implements— debris or pieces of wood scavenged from a dumpster. This took me back to my first impressions of the city, when it was more common for artists’ studios and contemporary art galleries to share city blocks, and students like myself turned urban detritus, the remnants of large-scale commercial enterprise, into art. “I like thinking of painting as work,” Fishman said. Indeed, in the studio she employs workers’ tools to make her paintings—big brushes, plasterers’ knives, and broom handles, among other repurposed objects.

What Fishman collects today might be artifacts of future luxury apartments, the construction of which has displaced the kind of local stores that once supplied her with art materials: Pearl Paint, David Davis, and New York Central, to name a few no longer in business. She still sources Williamsburg oil paints, although they’re no longer ground by Carl Plansky on Milton Resnick’s paint-grinding machine. Vasari and RGH supply her with other colors, into which she mixes cold wax and sun-dried linseed oil to make her color more sticky, viscous, or fluid, depending on the painting’s needs. Fishman’s powerful and sweepingmarks belie the slow labor of preparing huge quantities of color. Mixing enough Prussian blue at just the right consistency to scoop up onto a twelve-inch plastering knife takes far more time and sweat than the stroke itself. It’s the painter’s distinct craft to know how opaque or transparent the mixture will be, how it will dredge up the color beneath it when skimmed across the surface, or how it might skip over the bumpy weave of linen.

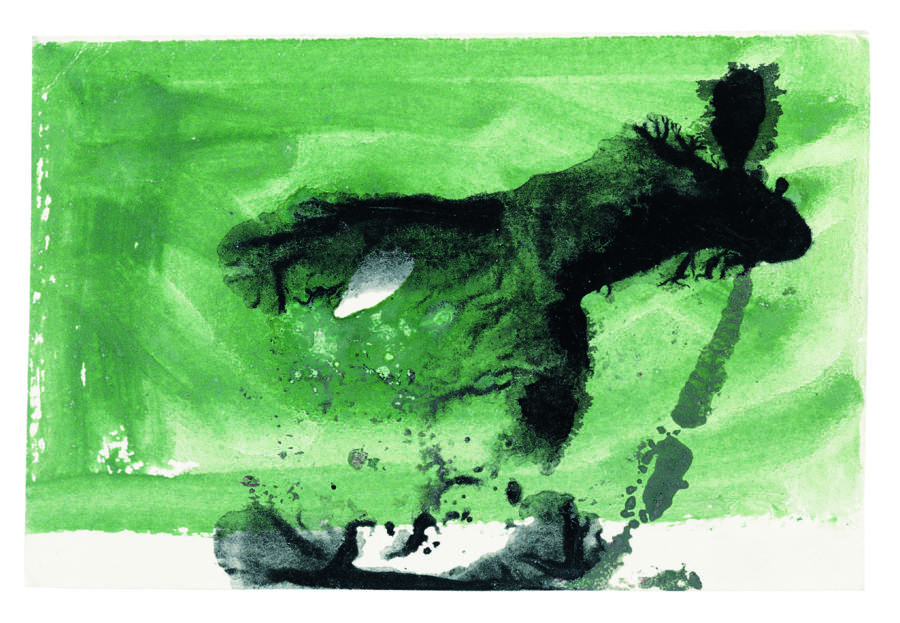

Louise Fishman, Untitled, 2016, egg tempera on paper, 4 × 6 inches; 10.2 × 15.2 cm

Louise Fishman, Mrs. Rumple’s Room, 1988–2011, oil on linen, 20 × 18 inches; 50.8 × 45.7 cm

Painterly facture is like handwriting in that a visual trace is left by the person who claims authorship of it. Much has been said about the relationship between Fishman’s gestural marks and the alphabet, both Hebrew and Latin. More recently, this relationship is evident in Fishman’s calligraphic use of egg tempera and ink on paper. There’s no going back once the color soaks into the fibers. Her hand’s movement is archived instantaneously in and on the surface, and the resulting composition reads like a signature. The graphic quality of her work is also noticeable in the chromatic and tonal ranges she chooses. Particularly visible in work from the last ten years, inky blues and iron-like greenish blacks are scumbled across the pale surface of her canvas. This is equally true in her larger-than-life oil paintings as in her postcard-size works on paper. High-contrast compositions recall traces of activity found in daily life, but not necessarily in art, such as skidmarks on the highway, printer jams, accumulations of sludge on city windows, redacted text from government documents, etc. Perhaps I’m misreading them, but misreading might be the name of the game.

Visual associations in Fishman’s work don’t often correspond to her titles, which are evocative in and of themselves (Soft Sorrow, 1998; Friend and Dear Friend, 2005; and Mrs. Rumple’s Rooms, 1988–2011, for instance). I’ve tried reading her work for legible subjects, which, aside from the 1973 Angry paintings and a few others, do not configurethemselves into intelligible representations. I’ve also tried reading her titles into the paintings, searching for the metaphors that connect materiality to language, and abstraction to image. This, too, seems to lose traction within a short time of looking or a longer period of attention. So, is her practice one of hidden meanings, one that is meant to analogize the effect of language? Or is language meant to exist outside of the rectangle, preserving the interior of the painting for private feeling?

Excerpts from Fishman’s biography have been recounted generously by her, lovingly by her spouse, Ingrid Nyeboe, and academically in the many pieces of writing on her life and work. Essays and interviews chronicle Fishman’s relationship to Judaism, and to Philadelphia and the art collections there; her participation in women’s consciousness-raising groups in New York in the 1970s; her identities as a woman, as a lesbian, and as a feminist; the lovers and friendships she has had; her contribution as a teacher; and her life as a daughter and as a partner. Many stories that make up her rich and full life are accessible and in the public domain. Sometimes they ascend to urban myth, passed down from friends, lovers, and teachers.

I first learned about Louise Fishman in the late 1990s in Provincetown, Massachusetts. At that time I was coming of age, identifying as an artist for the first time, and learning how to paint. The inheritance of New York Abstract Expressionism was all around me, particularly through the legacy of Hans Hofmann and Franz Kline, who had lived and worked on Cape Cod too. The confluence of that tradition with Provincetown’s established gay and lesbian community laid a foundation of what I thought painting, and a painter’s life, was and could be. So it was surprising, then, not to have encountered Louise Fishman’s name or work more frequently during my New York–centric education.

What had happened to suppress the feminist legacies of the 1970s within my cohort, or the dominance of gestural abstract painting within the contemporaneous art market?

The first decade of the twenty-first century was intent on shutting the door to the previous one. In school and in art museums and galleries,I was regularly reminded that “everything had been done before.” Throughout my interdisciplinary education, painting—and any one single medium—was antagonized. This was the “post-medium condition.” As a graduate student, I was asked, incredulously, what any one person could add to the history of painting. The latter was a burden, and painting as a discipline could only exist as a remix of the past, at best. Working abstractly was an act of quotation: a gesture was already a “readymade,” and making paintings was complicit in reifying the medium’s commoditystatus. At worst, it was a romantic and nostalgic form, out of touch with contemporary culture. Around this time, I probably looked past Fishman’s work and wondered how it was even possible to make gestural abstract paintings, given these incessant postmodern pronouncements and threats. Indeed, Fishman’s work has occasionally put me into the position of the naysayer, the skeptic, the person I don’t want to be. Frustrating.

I reencountered Louise Fishman’s work through Katy Siegel and David Reed’s exhibition, High Times, Hard Times: New York Painting 1967–1975, which took place while I was in graduate school. I now teach the catalog from that exhibition to my own graduate students. Approaching the age Louise Fishman was when I was born, it’s odd to realize that the last couple of decades have already witnessed numerous shifts within the field of contemporary painting, several of which can be charted through her work and career. Over the years, Fishman seems to have oriented her practice toward certain enduring points of reference: Rouault, Cézanne, Soutine, Turner, and Mitchell. These artists shine bright in her constellation of influences. In turn, Fishman has become a lodestar for many contemporary painters. Lately I’ve seen her influence emerge in the work of many of my peers and friends, including Keltie Ferris, Dana Frankfort, Fox Hysen, and RJ Messineo.

It’s significant that Fishman’s work doesn’t ask to be liked, as in a double-tap on Instagram; that it refuses easy reads—either via the screen or in person; and that it complicates the expectations of gestural abstraction, and the presumed identity of the maker. When most art is consumed through the internet, briefly, and attention is quickly redirected to the next page or topic, Fishman’s work, full of strong movement, is radically slow and inefficient. Its physicality, scale, and color are barely translatable to digital space; they chafe in the digital realm. But this resistance only gives her practice more traction.

It might sound obvious, but a painting doesn’t exist until it’s made. In the Western tradition of covering the canvas, color gets applied to the surface. It’s very simple. So why, then, is there so much feeling, history, language, education, trade, and meaning piled onto this ancient discipline, woven through its history and practice? Louise Fishman’s paintings ask this question. Their appearance tells the story of their own making—it’s all in plain sight at first glance. But, ultimately, they are difficult, private, interior. They embody the riddle of the medium.