2024

Maja Ruznic: Gouaches, Karma Books, New York, 2024

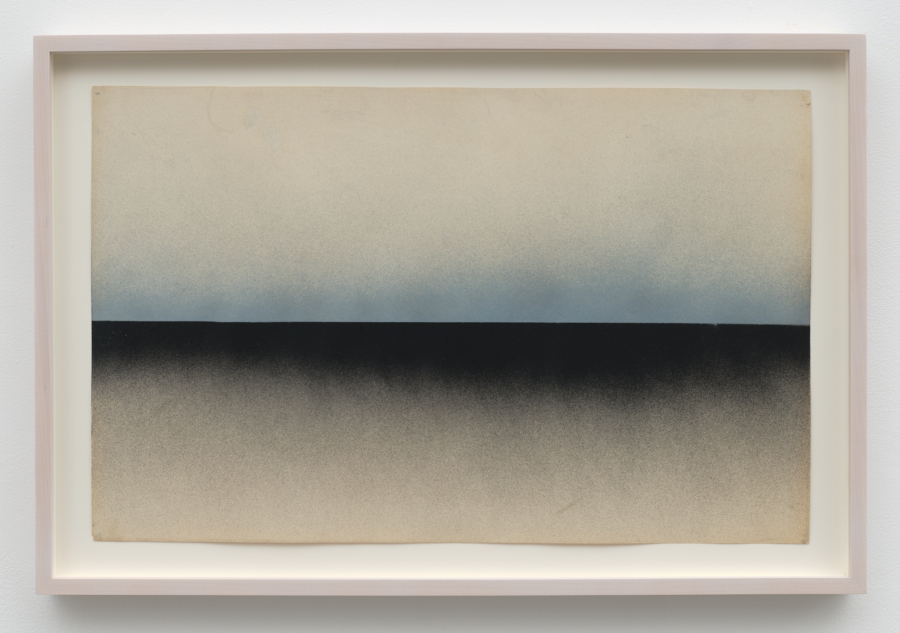

In Maja Ruznic’s series of jewel-toned gouaches on handmade paper, abstract shapes, both hard-edged and organic, morph together and shift apart. Singular and multiple figures, faces, and body parts also abound—some with sinuous lines delicately articulating or sensuously undulating over the surface. Looked at in succession, one gets the sensation of opening up a series of doors in a long hallway—these works are all in the same house, but each vista is different. The visionary DNA of Hilma af Klint, Paul Klee, Mark Rothko, Agnes Pelton, and others is present, along with any number of Outsider artists, particularly female mediums like Madge Gill or Agatha Wojciechowsky. While some of these artists had a direct impact on Ruznic’s work, and others only skirted the periphery of influence, it is important to trace her artistic origins because work this good does not occur in a vacuum. More often than not, artists like Ruznic are relegated to the sidelines of art history, overshadowed by their male contemporaries. I would like to place her firmly within the trajectory of certain modernist lineages, but also to compare her work to that of other women artists who share not only formal concerns but also an investment in those histories and beings beyond the visible.

Beginning in the 1930s, the Surrealist Roberto Matta explored in painting visual metaphors for his inner mental landscapes, often pouring his oils onto canvas while in a semi-trance state in an effort to directly access and record the contents of his psyche. To describe the resulting phantasmagorical works, Matta coined the term inscape. The Surrealists called this avoidance of conscious intention “pure psychic automatism,” a concept they appropriated from s.ance mediums, jettisoning its Spiritualist trappings in lieu of more psychological goals. The possibility of mapping the terrain of the subconscious—with its traumatic memories, desires, and mysteries—was attractive, and the idea of inscapes migrated out of Surrealism and into other artists’ practices. Works such as Here, Sir Fire, Eat! (1942) pulsate with the invisible and mysterious energies that Matta infused into his paintings while in a state of poetic trance bordering on the shamanic. Ruznic shares this ability to magically imbue a work with a sense of psychic immediacy, as if pouring out the contents of her subconscious without mediation onto paper.

As a means of dealing with painful childhood memories of the Bosnian war and years living in migrant camps, as well as her experience with postpartum depression after the birth of her daughter, Ruznic began experimenting with various therapeutic remedies. Reiki, yoga, Jungian analysis, and meditation all helped to mitigate her psychological discomfort, but also activated her imagination in new and visionary ways. Holotropic breathwork in particular enabled her to experience altered states of consciousness through accelerated breathing exercises.1 The ensuing cathartic, healing confrontations with past trauma opened a floodgate of hallucinatory imagery that has since fueled Ruznic’s creative practice. Memories, alongside other ephemeral matter, flowed in through this newly opened portal into her subconscious and she began to record what she could grasp through automatic writing and drawing. Ruznic likens this experience to an initiation of sorts, through which she receives mysterious “downloads” of information from other dimensions.2

Meditating in her studio and listening to certain kinds of music (such as Sevdah, blues, and Fado) prior to setting to work has become a regular practice for Ruznic and allows for archetypal imagery to flow freely.3 The presence of ancestral spirits is strong—for example, she often feels the influence of her grandfather, who was an artist and a basket weaver, and, with her grandmother, sold clothing in Bosnia that they had purchased in Greece. Ruznic’s affinity with textiles, especially the vibrant, woven rugs of Muslim Bosnia with their geometric designs and unpredictable color combinations, is evident in her work. Works such as Hearing God (2023), for example, share certain structural commonalities with weaving, like the grid pattern. Other works share various textile characteristics—for example, the ragged, torn edges of the paper resemble fringe, while some of her surface lines bring to mind embroidered overlay. Ruznic’s maternal lineage is Muslim, and her resulting familiarity with the spiritual dimensions of abstraction is significant to understanding the underpinnings of her gouaches. The prevalence of textiles in Muslim life (often used for daily prayer) contributes to a shared visual language divorced from representation, tied instead to nature and spirituality as ciphers for paradise. In addition to layered geometric forms, there are floral and linear elements in Ruznic’s work that resemble the embroidery on ethnic Bosnian costumes as well as rugs.

The artist that consistently comes to mind when viewing Ruznic’s work is Klee. His translucent watercolor compositions and simplified, iconic imagery set into geometric patterns perhaps emerge from some of the same sources as have influenced Ruznic. In 1914, early in his career as an instructor at the Bauhaus, Klee took a study tour to North Africa that would have profound implications for his artwork. Staying in Tunisia for two weeks, he was inspired by the light, the geometric formations of the Islamic architecture, and the mosaics, rugs, and other non-representational d.cor of the mosques and domestic interiors. In a series of watercolors, Klee translated all that he encountered into a new visual language that utilized grids of intensified colors with abstract forms. He was accompanied on this trip by the German artist August Macke, who similarly, albeit less intensely, incorporated the country’s distinct quality of light and architecture into an abstract vocabulary. Both artists created flattened surfaces that wove together bright bands of color into carpet-like compositions. The deep reds of cloth from the Maghreb are everywhere in Ruznic’s gouaches, reminding us that her childhood in Bosnia was also infused with imported Moroccan rugs. That said, on a different note, textiles also formed the makeshift migrant camps she lived in with her mother after their escape from the war, providing desperately needed shelter but also signifying displacement, anxiety, poverty, and exile.

These gouaches also contain ghostly figures, visitors from the ancestral realms, that flutter in and out of view, peering out at us. Shadowy apparitions stand like silent sentinels; fragmented faces emerge either alone or in groups. It’s as if Ruznic sent out a call to the Other Side, and a host of entities heeded the invitation. We are greeted everywhere with curious staring eyes and we get the uncanny feeling that they are looking at us as much as we are looking at them. There are distinct masculine and feminine presences here, the latter figures draped in cloth, next to flower-and-leaf-like forms. Sometimes within pink backgrounds are lines and forms suggesting female body parts, with apertures that hint of genitalia and childbirth, most certainly reflecting Ruznic’s own experience with procreation. I cannot help but think that, as the daughter of a single mother, they represent the artist’s female ancestors, hovering protectively around her in another dimension, captured on paper in a moment of clairvoyance.

Returning to the trance-like state Ruznic enters while creating her works, there is a direct process and visual link to important mediumistic women artists of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, such as Gill, Wojciechowsky, Georgiana Houghton, Paulina Peavy, and, of course, af Klint. Although Ruznic makes no overt attempt to contact the spirit world, her use of “psychic automatism” as a working method and invocation of certain kinds of imagery begs for a comparison. Some of her gouaches hold an electrifying network of lines that flow over the surface in a manner reminiscent of the portrait drawings made in trance by Houghton, a British medium. The work of both artists feature elegant arabesque webs that contain an energetic charge, a unifying life force visible only to certain individuals under certain circumstances. Ruznic’s abstracted flowers, vegetation, and natural forms, bursting with vibrancy as they radiate in a rainbow assortment of colors (pink, orange, powder blue), are distant relatives of those extraordinary early-twentieth-century paintings by af Klint. The Swedish artist understood her abstract visual language, informed by s.ances, to contain important spiritual lessons destined for future generations. Another comparison could be made with the German Spiritualist Wojciechowsky, who, while living in New York City in the early 1950s, practiced automatic writing and drawing, recording an entire alien script in notebooks. Her brightly colored, mediumistic drawings often contained faces that her sitters recognized as deceased friends and family members. Ruznic’s paintings, like Wojciechowsky’s, feature distinct humanoid entities that appear to manifest out of the ether, eager to be recognized and communicate. Sometimes only their eyes are visible, calmly assessing us.

New Mexico has long been a favorite location for artists experimenting with light, nature, and spirituality, with Georgia O’Keeffe being the best-known example. It was the Theosophists who predicted that the New Age would be born in the west, with its special light and landscape. The American Transcendentalist artists took this call to heart and, while living in New Mexico in the 1930s and ’40s, created abstract paintings meant to capture the Theosophical notion of “vibrations,” meant to expand consciousness. Such ideas were introduced in the influential 1902 book Thought-Forms, written by the Theosophical leaders Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater, which provided a color chart outlining the impact of certain hues on the human psyche. This text was an instrumental guide to generations of abstract artists, beginning with af Klint and Wassily Kandinsky and then onto the American Transcendentalists. Emil Bisttram, Raymond Jonson, Florence Pierce, and others, all under the spell of pioneering Pelton, experimented with the esoteric effects of color and form. Living and working in New Mexico, Ruznic is heir to a long line of modernist painters influenced by the location’s particular light, landscape, and aura. In addition to the crystalline light of the region, which was thought to promote spirituality, it was also the sense of freedom and dynamic energy that Theosophists believed heralded the west as the location for the re-enchantment of humanity. While there can be no pictorial equivalency ascribed to this, Ruznic’s sense of pushing boundaries and psychic exploration certainly puts her in this visionary genealogy.

In Jonson’s The Mystery (1937), the presence of ghostly forms within abstract shapes and the work’s bright color palette evokes Ruznic’s The Spleen Song. Bisttram’s Mother Earth (1940) can be thoughtfully compared to Ruznic’s House Games III— both experiment with turning discs in space. Pelton uses a soft, pastel palette to create atmospheric images that project an otherworldly ambience; in works such as Ascent (1946) and White Fire (1930), blues and violets emanate light as other shapes, symbols, and colors manifest out of the gloaming. So many of Ruznic’s gouaches echo Pelton’s use of close tonalities and thin veils of amorphous color to suggest transcendent states of mind and natural cycles. In the biomorphic forms and ethereal colors of Pierce’s Blue Forms (1942), we can again see Ruznic’s New Mexican artistic heritage. The Russian polymath Nicholas Roerich’s movement, Agni Yoga, informed by Tibetan Buddhism, was of great inspiration to the Transcendentalists, and his paintings have even more in common with Ruznic. For example, his 1924 Burning of Darkness depicts a sacred fire being carried out of an opening in a mountain by what the Theosophists called “the Masters of Ancient Wisdom.”4 Such occult symbolism is almost an aside to the masterfully applied multitones of cobalt blue, purple, and violet, whose intensity vibrates off of the canvas, expanding outwards like ultraviolet light itself. Although slightly more representational, this work bears much resemblance to a number of Ruznic’s gouaches in which deep-blue tones vibrate against each other to great effect.

Finally, the Abstract Expressionists: Rothko in particular bears comparison to Ruznic. In No. 3 (1947), he, like Ruznic, plays with colored forms that expand outside of boundaries, suggesting body parts here and there. In the same way that a shaman or magician invokes entities to appear, both artists have the power to call forth, to demand that the invisible presences surrounding us make themselves known. In her powerful Nana’s Rug and Rothko’s Heart (2023), Ruznic touchingly aligns her ethnic heritage with Abstract Expressionism, alchemically associating textiles and Rothko’s later, expansive color planes. This work shares with his No. 64 (1960) deep red and burgundy tonalities—both paintings speak of blood, pain, and trauma, as if the act of painting performed an exorcism of buried feelings. Another Abstract Expressionist that comes to mind when looking at Ruznic’s work is William Baziotes, whom, in paintings like Pierrot (1947), brings forth archetypal forms embedded in luminous surfaces that exude a quiet but powerful presence. As with Ruznic’s gouaches, upon first glance they give the impression of spontaneity, but on closer consideration seem as crystallized and timeless as petroglyphs on an ancient site.

As Matta demonstrated in his inscapes, the multidimensional nature of human interiority is a rich terrain for artistic exploration. Ruznic has taken her place amongst a lineage of unfettered creators seeking to visually record their strange encounters within the limitless confines of their own psyche. Such artists have often operated outside of the mainstream, relegated to the sidelines for a variety of reasons in a world where any spiritual seeking is regarded with suspicion, if not derision. This situation appears to be changing and Ruznic’s body of work speaks directly to many contemporary concerns about the continued validity of painting and of art as a therapeutic tool, both for the artist and the viewer. Like a modern-day alchemist, Ruznic is compelled to mix the complicated and volatile elements of migration, exile, motherhood, as well as other disparate but compelling emotions, into a healing elixir destined for a troubled age.

1. Holotropic breathwork uses accelerated breathing to dispel stress, fears, and anxiety and helps its practitioners to cope with traumas from the past by allowing one to access parts of the psyche that cannot be reached under normal conditions. It was developed by Stanislav and Christina Groff in the 1970s to achieve altered states of consciousness for therapeutic purposes.

2. Maja Ruznic in conversation with the author, January 15, 2024.

3. Sevdah is a Bosnia folk music tradition based on past oral traditions. Translated as “black bile,” it is a melancholic and poetic music that speaks of amorous longing. Fado is a Portuguese popular music tradition that references the beauty and sadness of human destiny.

4. This concept is similar to the Theosophical notion of “Ascended Masters”— enlightened beings who were once human but who now assist humanity on a spiritual plane of existence.