January 11, 2020

Mark Flood: Protest Signs from 1992, published by Karma, New York, 2020.

Download as PDF

Mark Flood: Protest Signs from 1992 is available here.

1992 was a leap year. Would there be a leap of faith, or one from the nearest rooftop? On the one hand, the Cold War was over, the European Union was founded, apartheid had been brought to an end, the last nuclear test had been conducted in Nevada, and the very first text message had been sent. On the other, seemingly jammed into an empty pocket, America’s economy had tanked under the Republicans, war raged in Bosnia, and the acquittal of four white officers of the LAPD, whose brutal beating of a black man had been caught on video, set off six days of rioting that left more than sixty dead, with damages in excess of a billion dollars. So much for the motto: To Protect and to Serve. Most grim was the reality of an ongoing nightmare: more than 100,000 dead of AIDS in the United States. Conservative politicians and their supporters saw the epidemic as a form of divine retribution, good Christians all, believing it deserved condemnation and neglect. A gauntlet had been thrown down, the “Culture Wars” had begun, and in the battles since and those before us now, war presents itself as perpetual, the polarities never reversed: us and them.

While twenty-eight years have passed, 1992 might as well have been yesterday. Back then, half a million marched on Washington in support of abortion rights, Sinéad O’Connor was vilified for tearing up a photo of the Pope on live TV to protest the sexual abuse of children by the Catholic Church, thousands of Haitian refugees were being deported. Today’s headlines are easily interwoven, especially when we consider that police brutality and the killing of unarmed citizens, mostly of color, has now become commonplace—despite cameras within nearly all our reach. The Revolution Will Not Be Televised? It will, and always will be, but it may not make much difference. How far have we come? Oh well, whatever, Nevermind.

1992 was also an election year, and the Republican National Convention would be held in the bright red state of Texas, in Houston’s Astrodome. George H.W. Bush was running for reelection. With the country in recession, and despite those “thousand points of light,” his prospects were dim at best. Republicans were looking backward, tethered to the past as they usually are, relying on Nixon (Bush thanked him for his wise counsel!) and Reagan for the values and vision of an America they believed was theirs alone, with RNC chairman Rich Bond insisting, “We are America, they are not.” At the convention, which would turn out to be the “Gipper”’s last major public appearance, Reagan self-servingly intoned: “Whatever else history may say about me when I’m gone, I hope it will record that I appealed to your best hopes, not your worst fears, to your confidence rather than your doubts.” (Let history take note: he got this entirely backward.) And concluding: “May each of you have the heart to conceive, the understanding to direct, and the hand to execute works that will make the world a little better for your having been here.” It’s possible this was meant with a measure of sincerity, since Reagan had made it far worse for so many. And in his appeal to noble service we have a fact that should be more widely known. “Make America Great Again” was Reagan’s slogan in his 1980 campaign, later swiped by Roger Stone and offered to Trump, who, discovering it had never been trademarked, immediately had his lawyers do so. And here we are, in these grating, greedy, unforgiving MAGAnanimous times.

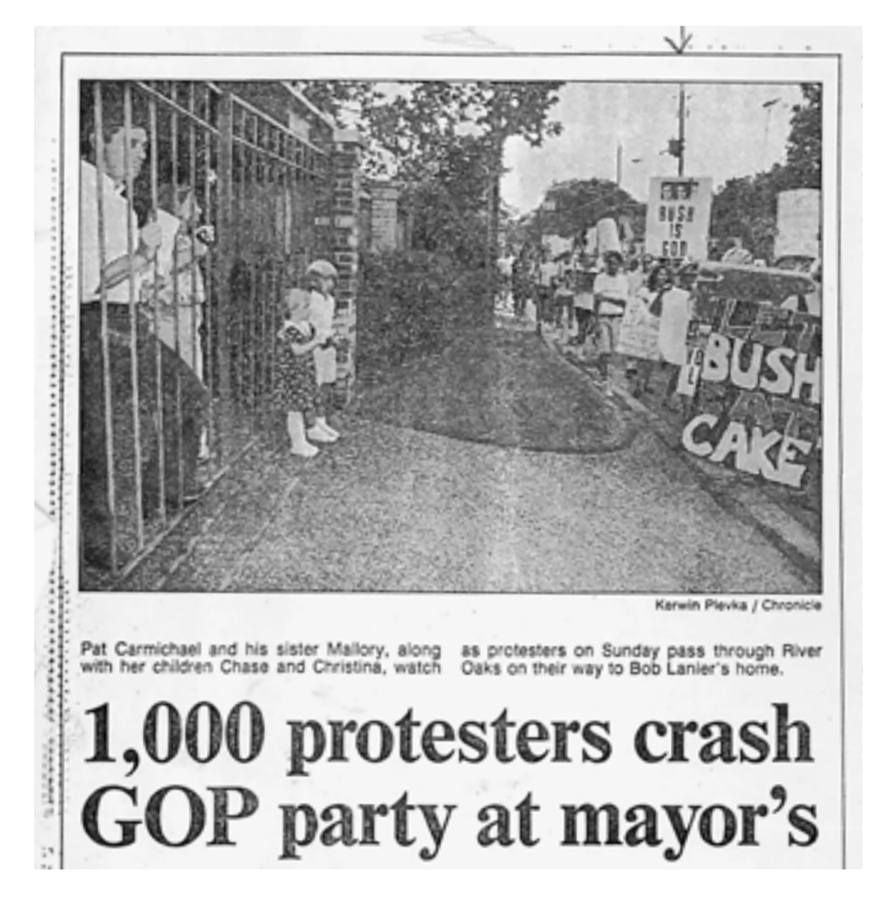

Around the country, there would be marches against the dangers that another term for Bush and the Republicans held, and in a heated-up Houston that summer of ’92 in particular. The artist and mocking punk rocker Mark Flood, who had once fronted the band Culturcide (the murder of culture? or by its own hand?), was tasked with making signs for these protests, and he readily, if unexpectedly, rose to the occasion. While it’s claimed he was “apolitical” (hah!), more resonant is the surprise that his signs, in contrast to the conventional condemnation and sloganeering we’re familiar with in activism, freely engaged with confusion, an intentional screwing with the issues of the day and, without any crystal ball, events to come. Of course George H.W. featured in many of them, but with a couple of odd partners in crime: tricky Dick Nixon, who resigned the presidency when he faced having to choke down a piece of impeachment pie, and Arnold Schwarzenegger, a good ten years ahead of the Terminator hero taking on a new part to play, as California’s Governator. Most of the signs incorporate text, all caps, always declarative, and a half dozen alternately taunt and advise: GET A JOB or BE A NARC. While Flood is the author (anonymous at the time), because Bush is the face of these statements, he’s the speaker. BE A NARC in ’92 was especially notable, given Bush’s “war on drugs” and his administration looking the other way where narcodictator and CIA asset Manuel Noriega was concerned. (Hey, you can’t have a war on drugs without the drugs! And contra to these efforts, any truth to the rumor that the CIA flew some of the coca into the States, rather than keeping it out? There’s a question for “hero” and former head of the NRA, Oliver North.) The sign in which Nixon is paired with Bush, as if they were running mates, cheers on: FOUR MORE YEARS. Schwarzenegger presides over the ridiculous solemn declaration: BUSH IS GOD. What on earth did marchers make of all this? And people along the parade routes? There’s a photo from one march where a cop seems barely to register a passing sign with a grainy silkscreened image of the LAPD’s beating of Rodney King, captioned: VOTE FOR LAW & ORDER.

These documentary photos place Flood’s signs in necessary context—with those made by others in attendance. A young man’s placard in one equates Bush with “RACISM CLASSISM HOMOPHOBIA.” Elsewhere, signs are carried by members of ACT UP (imploring Bush to “Stop the Nightmare” of AIDS) and the Gray Panthers (demanding “Health Care For All”). One sign declares: CENSORSHIP IS POLITICAL ABUSE. Flood’s signs are just as direct, if slippery. Surrounded by those others, what does it mean to carry a sign that says FREE THE RICH with a rippling American flag? Ever the provocateur, Flood must have caused some at these events, whether participants or bystanders, to wonder aloud: Whose side are you on? In a photo published in the Houston Chronicle, marchers only a few feet apart carry signs that proclaim BUSH IS GOD and jeer LET BUSH EAT CAKE, while two blond tykes stand in front of closed McMansion gates. The little girl seems hesitant, not knowing whether to clap or to cry. (And where are they now? Approximating their age from 1992, they would be in their mid-to-late 30s today. Did they vote for Beto or “lyin’ Ted Cruz”?) Back in ’92, would even the most die-hard Bush supporter carry a sign equating him with God? True to perverse punk roots, and in Texas they can be awfully twisted (Butthole Surfers, anyone?), Flood’s sheer delight in causing confusion amounts to a subtle surprise attack: an amBush in broad daylight. As for his signs seen amid the rest, ACT UP’s were surely created by graphic designers, while the Gray Panthers’ are straightforward, and the others, as at any protest march, were clearly homemade. Mark Flood’s have another presence entirely, not least for their larger size, but also because they are graphic without design, straight-shooting while also insincere, crude and composed at the same time. In other words: Art, or art. Flood’s work can be thought to drift intentionally from upper to lower case, sometimes within the very same frame. There is little doubt as to the sly knowingness of these maneuvers, evasive as they are.

What may have passed notice as these signs went by amid the clamor and visual noise of these events is the gritty artfulness of Flood’s signs, and our reading today of his decisions, since even if they were created quickly, considered choices were clearly made. One of the best FREE THE RICH signs features an image of Bush’s face that has stutteringly been slid downward so that there are multiple pairs of beady eyes above thin, pursed lips, the same which insisted: “No new taxes.” This is parenthetically subtitled Bush Monster. Another which horizontally repeats his stern face in overlay, with the proclamation BUSH IS GOD, adds dirty gold glitter around two fragments of his face. All that glitters isn’t God. The best Bush sign of all, needing no text whatsoever, which Flood titled Bush Skid with Stain, vertically repeats the face from top to bottom, and where the black ink veers erratically to the right (the political right) it’s as if tire marks from a car accident are visible at the scene of a crime, one that ended badly: at the top we see what appears to be a point of impact with reddish viscera spilled and dripping down. You have to wonder if Flood had Warhol’s Death and Disaster series in mind? Adding in a sprinkling of grimy glitter post–diamond dust Andy? (Later Warhol, with his bag of tricks.) The dark pop of the Electric Chairs and Race Riots eerily resounds with Flood’s use of the disturbing image of the Rodney King beating, as its degraded quality amplifies, as it did in Warhol’s off-register silkscreens of thirty years prior, the violence implicit in the abraded surface of the image itself. Flood keys up these images chromatically and optically, printing the Law and Order works orange on aqua, and orange on violet. Hazily citrus/blue, the scene could have been shot at night with an infrared camera. The sole Law and Order printed on raw cardboard with orange ink is particularly haunting, the seemingly lifeless body merged and submerged with the ground, an incident that might have been buried had it not been recorded, as if it had never happened. Among this group, one sign was printed a stark wire photo black and white, as it would appear on the front page of a newspaper. Another has been hit, possibly by chance (or more likely not), with a bloody red ink stain on King’s crumpled body. Even when realized in living—and expired?—color, these works exhibit a palpable rawness. Worth noting as well is Flood’s decision to place some of the flags on sickly yellow grounds, jaundiced, as if patriotism had been subject to disease, or wasn’t as heroic as claimed to be.

To see these signs today, framed and hung on a gallery wall, does not suddenly elevate them to the status of art. They always were. While in the here and now they occupy the space of painting, the fact that they occupied the public space of protest in 1992 only gives them greater resonance. They exist as both art and artifact. Even acknowledging a shift in use value across twenty-eight years’ time, and the brevity of their appearance in terms of what we may call street theater, we would have to set aside the only unassailable definition of art to consider these signs as ephemera. Because art is anything made by artists, which is entirely up to them and not us. A few that Flood gathered from the street after the marchers had dispersed are imprinted with the soles of sneakers and shoes. We identify significant works of art as markers in time. Flood’s Protest Signs</em may similarly be regarded as a form of history painting, as markers of where some stood, of what they stood against, of what they stood for. Flood’s Signs can be seen in clear relation to all of his text-based works, articulated in a way that is by turns acerbic, bemused, and irreverent, a voice that yet echoes from a year that was a year and a day. Look before you leap? Not when artists, as James Baldwin saw them, “are here to disturb the peace.”