April 5, 2012

Mark Flood’s Hateful Years, published by Luxembourg & Dayan, New York, 2012.

In the king’s bed is always found, just before it becomes a museum piece, the droppings of the black sheep.

—Nathanael West

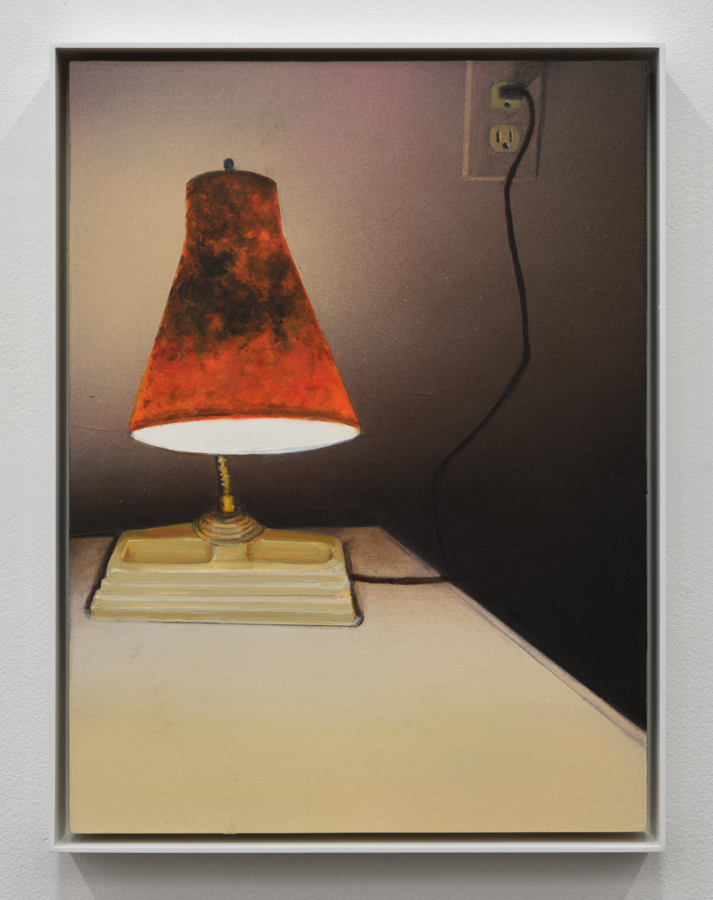

The Parents, 1986, acrylic on printed canvas, 24 × 18 inches; 61 × 45.7 cm

Idolatry, in its infinite forms, is the perpetual human epidemic. Deploying its most sinister two-pronged attack, idolatry both blurs and magnifies our collective vision. Mark Flood’s world and all its adept modes of creation counter-assault this phenomenon, suggesting we are a culture overwrought with a disease caused and spread by the obsessive attention we spew at our idols. For example, “Bieber-fever,” by Urban Dictionary’s online definition, is termed “a sickness that has recently become more common, where a girl, or boy, is extremely obsessed with Justin Bieber, and everything related to him. There is no cure found for this yet.” Indeed. In Ziggurat (1992), Flood outlines the progressive structure of this mass infection by assembling an ascending group of adjoining canvases. Upward from big panel to small, its pyramid reads: AUDIENCE, Fan, Really Big Fan, Obsessed Fan, Stalker—cascading levels of diagnoses. Flood’s research on idolatry and the proclivities that accompany it begin with the multifarious works that comprise the Hateful Years—the decades that are “pre-‘Lace’” for us Flood lovers—predominantly outlined in this book’s images and accompanying texts.

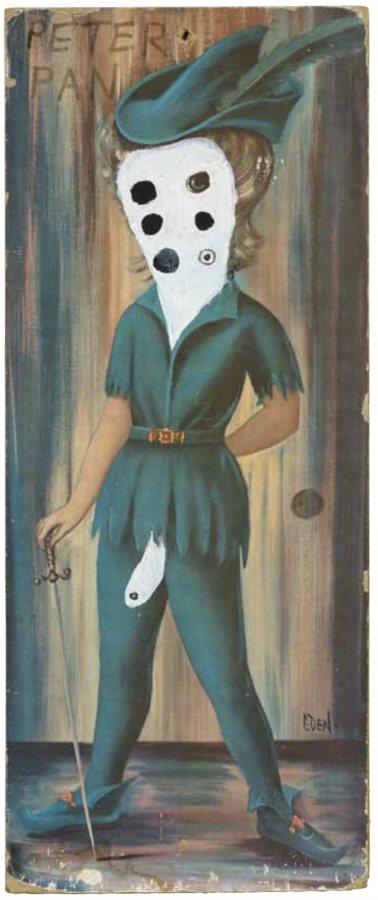

Peter Pan1987, Acrylic and marker on commercial print on cardboard, 24 × 12 inches; 61 × 30.5 cm

Sometime around 1980, Flood’s artistic production becomes sprinkled with “Idols” and “Monsters”—the Hateful Years’ foundation, their haunting guts—flea-market canvases and found modernist master lithographs overpainted typically with black acrylic. Their masked faces and mutated stick figures playfully stare at the viewer from each background’s conventional milieu. These works, with their anarchist tendencies and art-historical underpinnings, embody the notion of the anti-masterpiece. In The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, Julian Jaynes claimed that ancient humans considered their thoughts to come from gods and kings speaking to and through them. They obeyed the voices of their internal rulers for every need, as if they were physically present. Perhaps these disembodied “voices” we obey have not changed much in degree over time; we just imagine they belong to a different kind of “ruler.” Popular culture today presents these gods in one lump sum. Flood unveils this breed of psychology, reminding us of the cult of personality to which we’ve succumbed. In I Obey (1979), Flood’s tendentious message is the hypnotic shaman taking hold via the television set, the gods of CBS, NBC, ABC, and PBS.

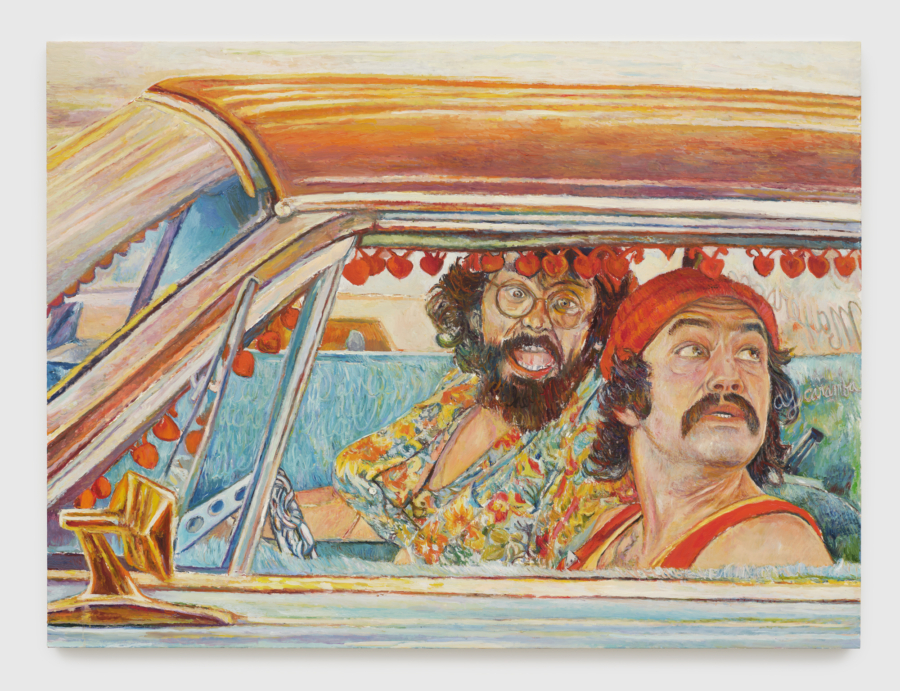

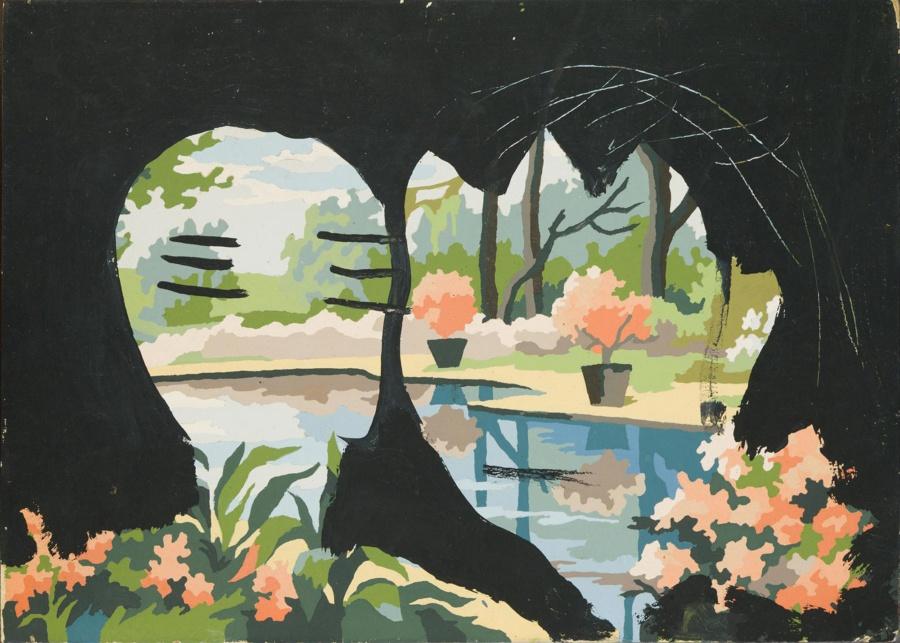

Floral Couple, 1989, acrylic on found painting on cardboard, 9 × 12 inches; 22.9 × 30.5 cm

But Flood’s idols and monsters trump and destruct the ones we find on our TVs and in our movies. Morphed, cut, and infected with disdain for uniculture, they offer insight into the way we as humans relate to one another. Moreover, these canvases are not just reconfigurations of our relationships, but by proxy, our power struggles, ultimately serving as grave markers of empty desires. They dethrone our kings and, frighteningly, empower the individual. Subverting the notion of idolatry in works like The Parents (1986), The Aristocrat (1986), and The Couple (ca. 1988), Flood’s subjects are defaced and erased, the mode of traditional portraiture subsequently vetoed, in flagrante delicto. Or take Peter Pan (1987) and all the abundant symbolism contained within J. M. Barrie’s cavorting tale. We all know Peter, born a contrarian rebel, cut off Captain Hook’s hand and fed it to a crocodile. Delve further into the flagitious history of this universal favorite, and the violent preface spirals into theories of Jungian archetypes, sexual sadism, black voodoo magic, and satanic fable. Hints of this are immanent in Flood’s picture, with Pan, sword in hand, fashioned with six eyes and spirited phallus. (Quite accurately, a Houston art legend reveals that when these Flood paintings were exhibited, they were seized as evidence in an alleged satanic cult investigation.)

Flood invites us to consider the refuse that follows this plague of ritualistic monotony. Recombinative appropriation thrives in the realm of the domestic, rife with material culture to expend, to sort, to reuse, to worship, to love, to discard. In the seminal texts of The Invisible Dragon, Dave Hickey writes that we gather around our fashion, sports, art, and entertainment icons as we would about a hearth, that we “organize ourselves in nonexclusive communities of desire.” Flood examines how our disease begins with these simple notions of pleasure—how an innocent teenybopper’s pinup-plastered wall begets an innocuous crowd of star-gawkers, but in Flood’s world at any moment the crowd could quickly morph into Nathanael West’s ominous angry mob, their disappointment over false idolatry unleashing a jihad that takes shape after humanity becomes nonsubjective globs. Idolatry is the scion of obsession, feeding our mass cultural infection.

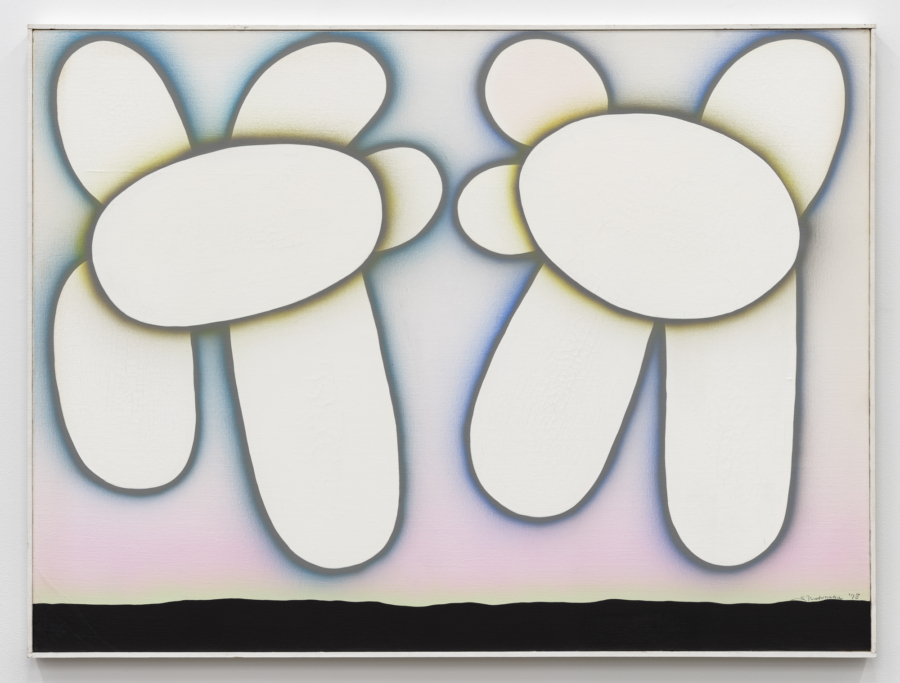

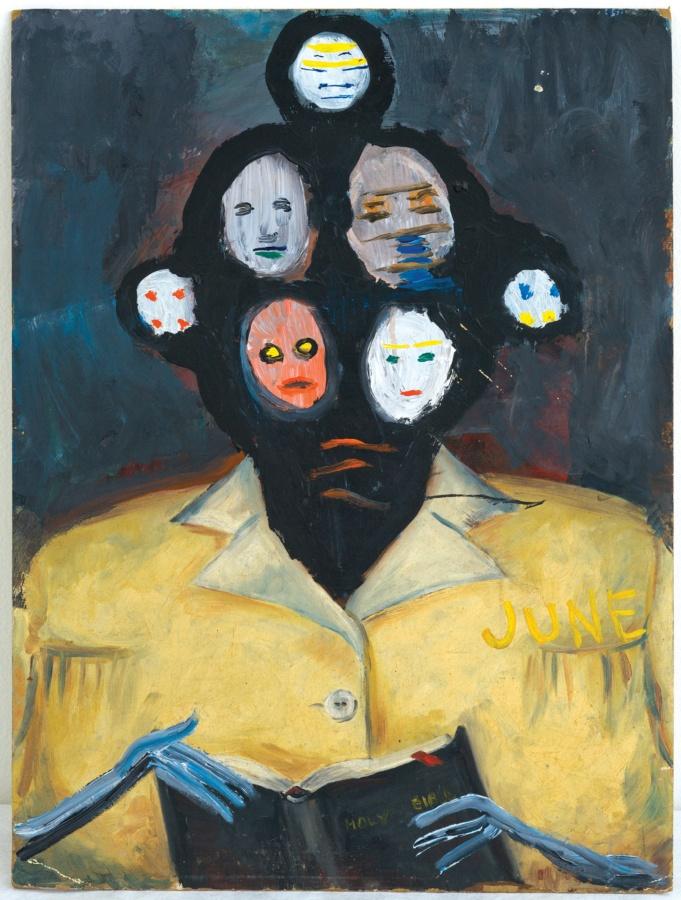

June, 1986, acrylic on found painting on cardboard, 24 × 18 inches; 61 × 45.7 cm

Flood’s idols and monsters serve as bellwethers for his later Hateful Years output, segueing into and around the celebrity canvases and collages. Similarly to the “Idols” and “Monsters,” the meaning of these crudely altered portraits is not determined by the subject’s identity, but instead by the very mutation of their flesh. Quasi-human figures dispense broken commands, their presence unearthing the totemic power found in even the most minor of celebrity. SEE THE NIGHTMARE. Flood’s is a world in which the flashes in the pan, the one-hit wonders reanimate zombified, and loiter—where the warped but still God-like voices of Justine Bateman or Tony Danza can command the viewer to perform the weightiest of tasks: BE GOOD, COMMIT SUICIDE, ENJOY LIFE, EAT HUMAN FLESH.

With all its unabashed contradictions, the common strain in Flood’s Hateful Years productivity is the deformity of this very notion of fame; and with each disfigurement there is a offered a correction, whereby Flood achieves the most honest answers about this cultural epidemic. It is as if Flood disrupts the gathering about the hearth, to say “See how monotonously sick we all are?” The tenacious human recycling impulse spews out a Corey Haim, a Don Johnson, a Hannah Montana, a Justin Bieber, like a vending machine. A season of American Idol, a Satanic ritual, what does it really matter? Inasmuch as Flood considers repulsion, he always offers a giant medicinal spoonful of seduction. And we remain about the ceremonial hearth, and we beg for more.