March 28, 2012

Mark Flood’s Hateful Years, published by Luxembourg & Dayan, New York, 2012.

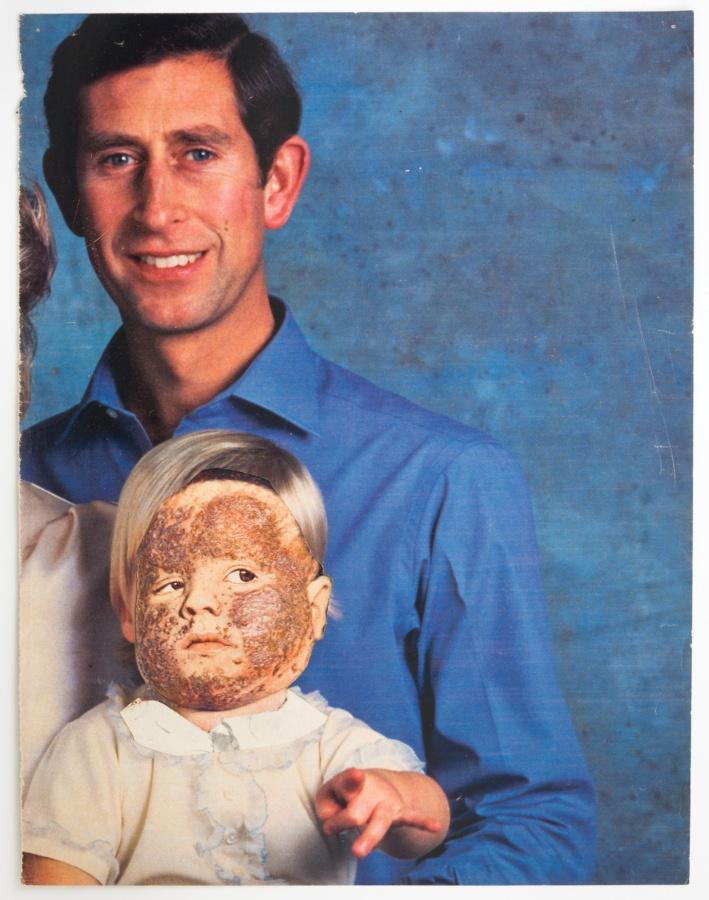

The Little Prince, 1984, collage, 13 × 10 in; 33 × 25.4 cm

One of the primary themes in Mark Flood’s work is America’s fetishization of newness and the attendant demand for a rapidly cycling supply of disposable cultural goods. Flood’s collages of celebrity faces propose that the ephemera littering our streets and fluttering in our recycle bins are, in fact, our most salient and inviolable historical artifacts. In a series that both debases and celebrates the plastic visages of outdated crooners and abandoned screen idols, Flood asks us to reconsider the jettisoned relics of our recent past. The uncanny familiarity of these works reminds us that our Rome is built on a foundation of Star and Tiger Beat magazines.

Because popular culture loops in a constant state of self-perpetuated obsolescence and reinvention, Flood’s celebrities typically come to us in incarnations that are slightly outdated, aesthetically stale, and vaguely embarrassing. Though an unaltered version of Flood’s Don Johnson poster remains trapped in a constant Miami Vice rerun without the possibility of reprieve, the artist’s cut-and-paste intervention has refashioned the actor’s face into a post-surgical nightmare laden with the promises of unexplored theatrical terrain. Though his hair, sunglasses, and holster remain intact, our interest is reinvigorated courtesy of a freshly applied graft that stretches waxy scar tissue from the actor’s forehead to the distant curve of an exaggerated lantern jaw. In a gesture that apes the heterosexual conventions that determined the tenor of the original image, this mottled expanse of face ignores all laws of physiognomic contour, save for a central column of ropey phallic veins that concludes with a cigarette dangling from a puckered flesh hole. “Do you love me again?” this version of Don asks us. “I did this for you!”

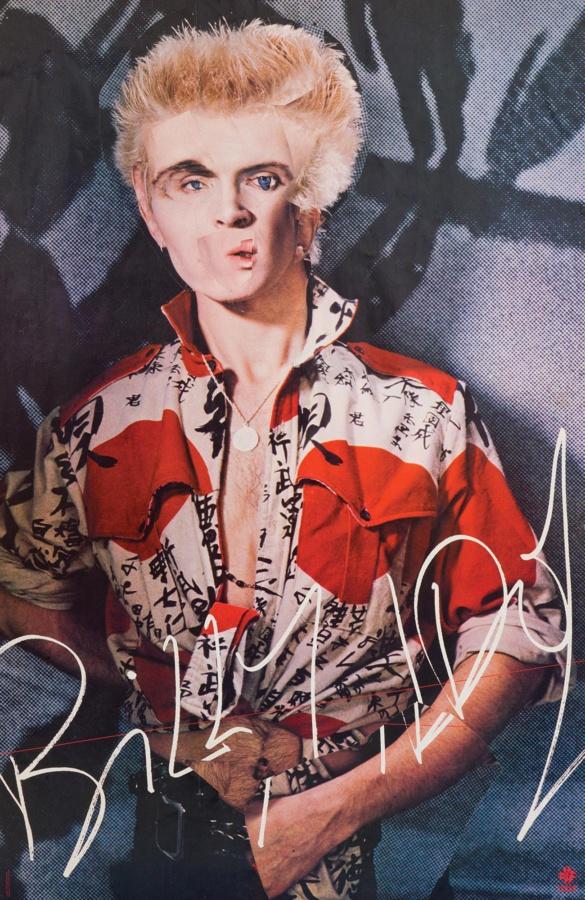

Billy, 1983, collage, 34 × 22 in; 86.4 × 55.9 cm

Executed before the Internet granted unfettered access to images and the technology to reproduce them ad infinitum, Flood’s celebrity collages required several duplicate posters as their source material, a critical detail in our understanding of their conceptual function. Unlike Warhol’s prismatic duplications of Elvis Presley or the visual echolalia evident in his twenty-five identical Jackies, Flood’s collages enlist compression and composite; they overpack, stuff, bloat, and cram; they fill themselves to the point of overflowing excess. In a gesture of Frankensteinian self-cannibalization, Flood’s celebrities alternately erase and consume themselves, their monstrosity the result not of accident or age, but rather an attempt at a reconstitution of the diffused self.

Central to these collages is the popular belief that the vessel of celebrity is too porous to hold meaning. Flood’s retrofitted faces aim to caulk the cracks, close the dams, contain the leaks; they seek to re-assimilate recently forgotten faces via a series of surface massacres that somehow both amplify and silence identity. In a collage of Adam Ant, Flood has allowed the singer to retain his signature hairstyle, but his customary horizontal slash of white makeup bisects a face devoid of features, a face that simply is not there. This conspicuous absence not only offers the illusion of a blank canvas and the false promise of an empty projection screen, but also isolates and exploits the absolute horror of the blown-out signifier. The message is one that calls into question our notions of interchangeability, disposability, and the corrosive qualities of indifference.

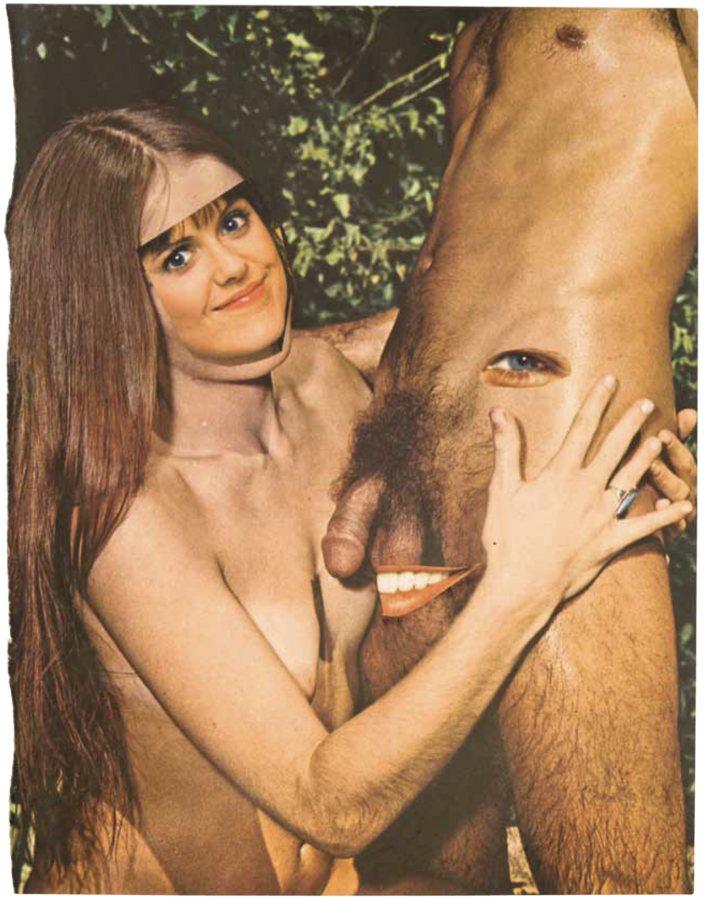

Untitled (smiling groin-face with celebrity-face girl),1986, Collage, 11 × 8 ¼ in. (27.9 × 21 cm.)

The rapidity with which we first inaugurate and later impeach celebrities and our insatiable appetite for unattenuated newness has created a system in which idols are constructed, in part, for the pleasure we find in their demolition and subsequent replacement. The celebrity collages examine how consumer culture attempts to erase itself, how the glossy paper trails that first buttress and subsequently sink our idols are eventually transferred into the invisible archives of the wasteland. Flood reminds us that our discomfort in encountering aged symbols of Hollywood glamour is little more than an anxiety connected to our own unstoppable hurtle toward death, that fame is simply a wheeling and wandering placeholder, and that any denial of these facts is little more than an exercise in plastic surgery.