December 10, 2020

Reggie Burrows Hodges published by Karma, New York, 2021

Download as PDF

Reggie Burrows Hodges is available here

There have been many schools of art, but in the end, there’s only one school, and it houses the artist. For those of us who admire painting and know something about its development through the ages, art history is a useful tool to describe why Braque is over there with the Cubists, and why Man Ray makes mischief as a Surrealist, and why Picasso is everywhere. And while these various schools—points of reference, really—help to contextualize what we’re looking at and why, they can be thought of as signposts, too, marking significant moments in Western cultural history, ranging from Italian Renaissance painting to Romanticism, Abstract Expressionism, and Pop: shifts in thought and ways of looking that have changed the critical language around art, and thus our thinking about it.

It’s a long road, that history, sheltered on either side by tall leafy trees, otherwise known as consciousness. Artists have walked and staggered along that road, sometimes blindly and always intuitively, because it’s a path filled with surprise and wonder, the very stuff that inspires you to make art in the first place. But it’s not a road you can map. No one knows its exact length or location because it’s in the imagination, and the imagination doesn’t have a specific locale, just those trees, and that long worn path, where fixed interpretations—such as those offered by art historians, connoisseurs, and the like—are OK, but not really the whole story, not by a long shot. That’s because talent can’t be accounted for, ultimately, and it doesn’t belong to any school, certainly Reggie Burrows Hodges’s talent doesn’t. He draws on, but doesn’t fix on, a number of schools—Color Field painting, abstraction, Depression-era realism—the better to articulate who he is, and means to be.

Every artist tells a different story than every other artist. But what unites them all is their relationship to space, and knowing what to leave out. You don’t want the painting to look unnecessarily heavy with pigment or ideas about paint, even if it’s Guernica (1937) (fig. 1). Indeed, what artists—OK, the best ones—strive for is a naturalness of expression, and to describe the world of paint and space their imaginations inhabit so it can live freely in their mind, and in your mind, too. During this, your time, and the artist’s time.

Guernica grew out of its own time, of course. A time of war and destruction. Yet Picasso made room for us, the viewer, in his rendition of all that chaos. See for yourself. Look at the gray, “empty” patches in his crowded, electrifying work; that’s the space he left for the viewer to project himself or herself onto. He wanted the viewer to live inside this painting, and to feel their own death and beauty in all that death and beauty. Mixed in with that anguish, though, there is the act of creation: the making of the world in Guernica. It’s an action painting in the sense that it moves—or your eyes move across it—from left to right and then back again, like a Japanese handscroll, while it stirs us to a kind of emotional action, or response: those figures of distress being uprooted and extinguished could be us, especially now, as this world becomes something else, and then something else again in all our current fear, waiting, and silence.

Fig. 1 Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937, oil on canvas 137½ × 305¾ inches; 349.3 × 776.6 cm

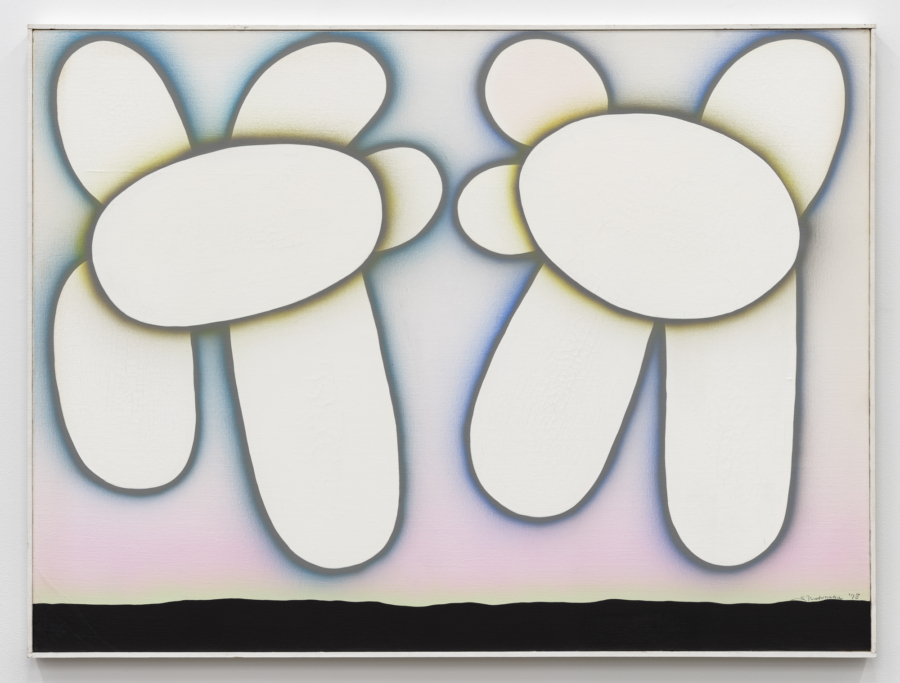

I’m going to put another image up now, right next to Guernica. It’s New York–born painter Helen Frankenthaler’s exceptional Nature Abhors a Vacuum (1973) (fig. 2). Let’s talk about why. To begin, each is about the transfixing power of energy, and how best to communicate that power in their work without losing a molecule of it.

While Picasso’s mid-career masterpiece is about death in the midst of life, or, more accurately, what life gives us—beauty—and what it takes away—beauty—Frankenthaler’s grand work is about the suspension of disbelief: death will not come as long as there is this earth, these mountains, that sun. Still, like the European master, Frankenthaler knew when to stop or to counterbalance all that delicious color and joy in the act of painting with the amazing nothingness of white space—those little rivulets that separate the drama of color and shape with a kind of visual pause where viewers can put up their feet, so to speak, and rest awhile.

What can it mean that I’ve begun this essay about Reggie Burrows Hodges’s first solo show in New York by talking about two contrasting works created decades apart and out of different circumstances by different artists? Your sense of art history might balk at the very notion of showing these slides side by side; it messes with your sense of order—of historical and emotional chronology. What in the world does Picasso’s canvas-based death have to do with Frankenthaler’s canvas-based life? Nothing at all, if you are thinking conventionally. But you can’t think conventionally when you look at Hodges’s rich, mysterious canvases. They scramble art history in your mind because they are about the love the artist feels, not only for what he’s doing, but what has come before: Picasso’s grays, the limitless sky stretching above all the trees on that long road of the imagination.

It takes a mature and confident artist to admit to influences, and Hodges is both those things. One could call him a postmodernist if that didn’t feel like another school he didn’t belong to, and, besides, postmodernism, so called, tends to leave love out. Hodges, down to his bones, is a romantic about painting. If stretched, one could call him a Romantic in the Age of Cholera. Whatever. Like Picasso and Frankenthaler, Hodges makes paintings about acceptance—about immortality, about being. And I don’t think I would have thought that way at all, had Hodges not expressed in his significant paintings an awareness of death framing life and a view of human connection as a series of illusory moments filled with so much. Nor would I have realized any of this if Hodges didn’t relay, in his intricately worked-out and free images, what a pleasure jumping into pleasure can be—sort of like a delicious giant pool filled with welcoming, temperate water. A giant pool shimmering under a phalanx of trees over that road where artists work out their ideas about death and life and color.

Frankenthaler took as the title of her painting a phrase of Aristophanes’s, or one that has been attributed to him: “horror vacui” can be found in any physics book, and I gather that what the philosopher meant by it is that nature contains no vacuums.

If you set a thing in motion, who’s to say that it stops anywhere? How marvelous. That means—or I take it to mean—that the eye doesn’t just stop when it looks at a painting. The image spins and spins in your mind, and then that image and your thoughts about it travel out into our world of particles, where your thoughts and that painting become something else, or something else again.

Could my eye and thinking spin with Reggie Burrows Hodges’s paintings? I wasn’t sure at first, meaning I couldn’t find my Guernica or Frankenthaler portal in his stories. I couldn’t rest awhile in his version of land and sky. At first the work felt “overall” to me, not in the Pollock sense of splattering and dripping cum on the window of the world, but overall in terms of the work’s emotional weight. At first, the paintings were all over me, meaning they prompted profound memories about sad Sunday afternoons sitting dully by myself, waiting for the game of life to begin, or to be cherished, or something. My memories were crowding his work out. Still, Hodges’s images were too vibrant and present not to drag me into the present. It took me a minute, but then I recognized what a big part memory played in Hodges’s work without me. Indeed, a lot of the larger canvases look like scenes in memory: delicate, amorphous, and too fine to take apart and categorize for art history’s sake.

Born in 1965, Hodges was raised partly in Los Angeles; as a teenager, moved to New York and Washington, DC, with his father, an entrepreneur. The politically minded Hodges spent a great deal of time trying to shield his son from the exigencies of racism without closing the world off to him. By 1986, Hodges was a student at the University of Kansas, where he played tennis on scholarship, majored in theater and film, and did coursework in African American studies. After graduating, he settled in New York, where he focused on music. From 1995 to 2010, he wrote songs for, and toured with, Trumystic, a dub rock group. In 2000, Hodges relocated to Vermont before settling in Maine in 2008, where he now lives.

Despite or because of his peripatetic lifestyle, art-making has always been a constant for Hodges. He recalled that, as a child, his father had a drafting table his son could share, but was warned to be careful with. So saying, Hodges’s father instilled in him a kind of reverence for workspaces and, by extension, the real stuff that goes into creation—such as discipline. These are extraordinarily disciplined paintings, and I’m trying to remember, just now, if that was one of the qualities that first struck me about them. After I got over my own memories, or felt free enough to share them with Hodges’s paintings, I could see, at last, the discernment and velocity framing his images. I think Hodges’s In the Service of Others: Consistency (2019) was the first of his larger paintings I ever saw. I’m sure that’s right. I remember feeling frightened in its presence; looking at the image was like standing on the brink of a mass I could not recognize. Were they mountains? Was it sea? Was it air? After a while I recognized the scene—a relatively “realistic” view of folks on a tennis court. One person is being handed a towel. But then the cinematic creepiness of the image—what was under that surface seen through the skein of darkness—compelled me to keep looking because I was afraid of it. How often can we say that about a work in our age of aesthetic transparency, in a world that rushes to categorize who we are and why, where everyone has taken some version of Google Art History?

Fig. 2 Helen Frankenthaler, Nature Abhors a Vacuum, 1973, acrylic on canvas, 103½ × 112½ inches; 262.9 × 285.8 cm

Fig. 3 Milton Avery, The Nursemaid, 1934, oil on canvas, 48 × 32 inches; 121.9 × 81.3 cm

For a time, I clung to Hodges’s details as a way of feeling I had control over the work, and not the other way around. For a time, I stood away from Hodges’s art so as not to be taken over by it. My eye and “I” could not find an area in the canvas where I could stand in collaboration with the artist. And yet, as much as In the Service of Others: Consistency frightened me, I could not look away. The artist was in control of my fears, as much as my pleasure. I could not look away because of the blackness. Blackness dominated the scene, and it was of a kind I had not seen before; it seemed to sink into the linen of the canvas, and then bleed out a little bit, and stain, but to be, at the same time, controlled by the artist’s hand with all its steady gestures.

Hodges begins by painting a raw canvas black. Then he paints his figures and their atmosphere on top of that. His hand is everywhere in his work, in control but not controlling. Shall we call Hodges’s work controlled bleeding? While painters such as Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, and the like managed their paint by splashing color here and there, their project was different from Hodges’s in a number of ways, including their use of color. While today we look on those distinguished paintings for the joy they express about physicality, the irrepressible eye, and a relative lack of fear when it comes to the decorative, there are, in these artists’ wonderfully gestural work, some shortcomings. Such as their use, or lack of use, of the color black, a hue that is of the utmost importance to Hodges, who has said: “I start with a black ground [as a way] of dealing with blackness’s totality. I’m painting an environment in which the figures emerge from negative space. … If you see my paintings in person, you’ll look at the depth.”

Black Ground: In Pursuit (2019) is emblematic of Hodges’s equating blackness not only with depth of field, but depth of person. What we see in this work: two partial figures, perhaps both male, standing or sitting under an umbrella. The smaller figure sports a yellow headband; the headband echoes the yellow in the smaller figure’s T-shirt straps. The taller figure sports a cap. Behind both figures there’s a hedge; the sun dapples the green leaves. Those are the general outlines of the painting. What we feel about it is also based on what we cannot see, which is to say Hodges’s subjects’ faces, and whether the older man is holding the umbrella over the younger person’s head—a potential gesture of such tenderness and concern that I had to look away from the image at first. Are they in shadow because of the umbrella, or because of the shadows that collect on our faces and bodies when we step outside of bright sunlight before our eyes adjust? Is that the moment Hodges is capturing here as well, the move from darkness to light? Hodges’s characters—all of whom I think of as characters in a giant narrative about American life as it’s played out in games and loneliness—often don’t have physiognomies with discernible features. Their faces are a black plane. Does this make them spooks? Ghosts? Are we ghosts now, as we wait for change in this ill world of the dying, framed by loneliness?

A fan of Milton Avery’s work, Hodges, like the legendary colorist, looks for, and renders, his figures’ essence as it lives and breathes in the political. In 1934, Avery painted The Nursemaid (fig. 3). Here a brown-skinned woman talks to another dark figure. The nursemaid, dressed all in white, holds the hand of a pink, or presumably white, child. As usual, Avery isn’t concentrating on the figures’ faces; he’s interested in their postures, and the strange echo of the nursemaid’s hands in those of her charge. It’s the hands, and the bodies as shapes made by paint, that are Avery’s focus, along with how the figures are alone together. To all of this, Hodges adds all that wonderful, unequivocal blackness.

In his lovely essay about the painter Beauford Delaney, the artist’s close friend James Baldwin describes how Delaney taught the writer to see the color black. Baldwin writes:

Though black had been described to me as the absence of light, it became very clear to me that if this were true, we would never have been able to see the colour; black: the light is trapped in it and struggles upward, rather like that grass pushing upward through the cement.1

What Hodges’s characters are pushing up past, and through: the idea that blackness is “heavy,” politically, artistically, and otherwise. When I look at the ambitious and devastating Intersection of Color: Garden (2019), I see the garden, a community space, but thankfully I don’t see sociology framing it—i.e., the garden as a “poor” space for the disenfranchised to gather and create a communal haven separate and away from whity. Rather, the painting is an exploration, first and foremost, of that most elemental of the artist’s endeavors: paint. What does this color look like next to that color? And if I build a world from the ground up, what does the ground look like in comparison to the sky? Black earth, black figures, a gray and white sky. What this teaches us about painting, and Hodges’s in particular, is that he does admit the viewer into his work, and wholeheartedly, once you get past your preconceptions about blackness, and what it’s supposed to mean, either as “pure” paint, or as a figure. While Kerry James Marshall might come to mind in works like Hurdling: Sky Blue (2020), the comparison is cosmetic: Kerry means for his superrealistic figures, faces, and situations to be seen for what they are; while Hodges is intent on starting another conversation altogether, one that begins and ends with the shapes he is making, and allowing you to make with him, if you let your eye roam while staying close to the canvas. Seeing as an event.

Sometimes, when I look at Hodges’s work, I think about black mirrors. Black infinity mirrors. I read once that artists ranging from Gauguin to Renoir had them and sometimes, at the end of a long spell of work, they would look into the mirror to refresh their eyes; it was a break from looking so intensely at color. Hodges’s black has a transfixing power as well, and I wonder if, when he paints a white canvas black as a way of beginning, if blackness has a similarly transfixing effect on him as well, and, if it does, does that lead to his paintings, which are dreams that are so awake with real life? Hodges’s paintings are not only recovered memories about growing up in Los Angeles, and then being an athlete, and then becoming a man and an artist, they are also memories of familial connection, or a way of thinking about connecting with family. In Big We’ll (2020) a little boy is taking off or trying to take off on his Big Wheel, while an adult man and woman stand nearby, protective and watching. The woman’s hand is resting on her hip: it’s a gesture that conveys so much about Black female being in a hostile world: My hand is resting on my hip for now, but it can be around your head in a minute if you mess with my child. The surrounding air is thick with possibility, warning, the remembered and felt concerns of Black parents, wonder. Perhaps the older man sees himself in that little boy, and in seeing that child take off into the world, there is so much he could say about its dangers—the older figure’s posture, like many of the men in Hodges’s stories, is a kind of shield and portal between that young person and the rest of the world—but now is the time for silence and watchfulness as the child, intent on discovering the universe for himself, takes off down a road to find his own wonder, and the school that will shelter him as he nourishes his own ideas about love, color, space, and the imagination.