December 12, 2020

Reggie Burrows Hodges published by Karma, New York, 2021

Download as PDF

Reggie Burrows Hodges is available here

The following conversation between Suzette McAvoy and Reggie Burrows Hodges took place on Wednesday, November 18, 2020, via Zoom.

SUZETTE McAVOY: Hi Reggie, since we’re both here in Maine, where there is a wealth of painters, I thought it would be interesting to talk about your work in this context. In particular, I’m thinking of that short video you recently made for the Portland Museum of Art, where you discuss the Winslow Homer painting Watching the Breakers, and begin by saying, “I may be known as a Maine painter, I’ve lived other places, but a history, a legacy, will now be attached to Maine.” Could you elaborate on what you meant by that?

REGGIE BURROWS HODGES: Yes. I was born in Compton, California, and I’ve also lived in New York. I now live in Lewiston, Maine. Through my time here, and various good fortunes in terms of my journey as an artist, I’m really proud to be known as a Maine painter, because significant relationships and development have happened here. There is such a rich tradition of painting in Maine and I’m proud to be a part of that.

SM: How did the video about Homer come about?

RBH: It was very exciting—the curatorial team at the PMA were seeking community voices for this project and were aware of my exploration of Homer’s work within my own. It started me thinking about my affinity and love for Homer as a painter. An interesting and unique story from my childhood was this significant piece of art above the mantel in my home in California. It was this sort of beach scene, a wave, but I didn’t know for the longest time who the artist was or where it came from. It was just a part of our home. It was very much something that you could have probably found at a flea market because my parents didn’t collect art, though we had prints and things that mostly served as decoration.

Advance thirtysomething years later at a museum and I see this painting. It was Weatherbeaten (fig. 4). I had no idea for all those years that I had been looking at this Homer painting. Now, it was no influence on me at the time other than, “Oh, what a coincidence.” Because although I was involved in artistic expression then, my main focus was music, not painting; but such an incredible association—it’s come full circle.

SM: That’s a wonderful story of a really rich visual memory to carry forward, and to think—you’re now living in the land of Homer, so to speak. One of the things that really struck me in the video was how you described Homer’s painting in such musical terms. You spoke of its “mood and emotional cadence,” “the tone,” and Homer’s “soft hand.” Which brings to mind your own background as a musician. Do you see a connection between the two?

RBH: Yes. As I continue on this journey of trying to express an internal feeling and present that onto a two-dimensional surface, one of the things I strive to be able to convey is that feeling of space that you have within music. I’m speaking from having played in a dub reggae band—dub being this form of basically distilling down a larger composition to create this over-enhancement of space.

Fig. 4 Winslow Homer, Weatherbeaten, 1894, oil on canvas, 28½ × 48⅜ inches; 72.4 × 122.9 cm

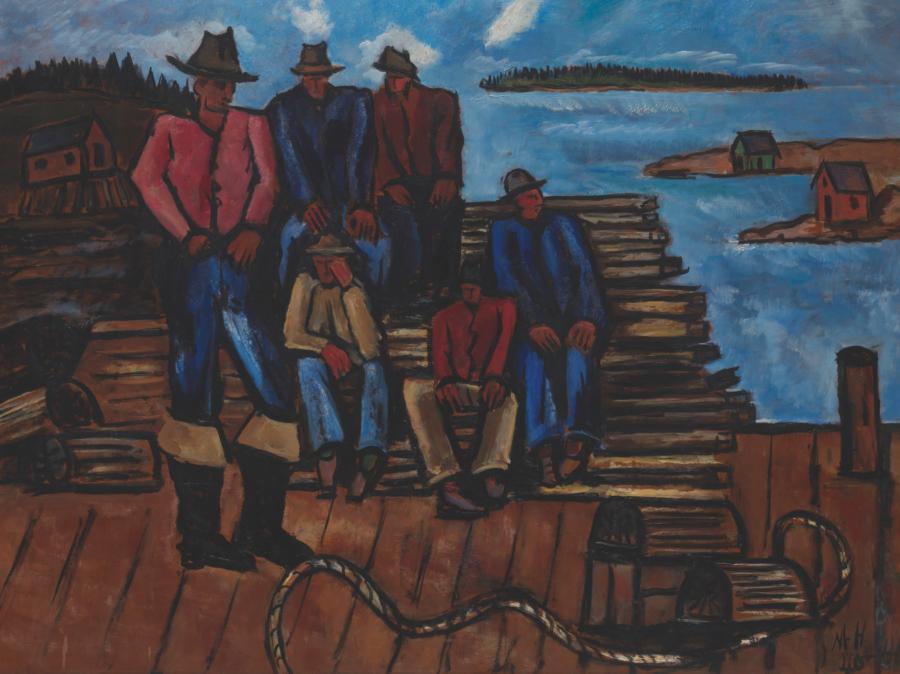

Fig. 5 Marsden Hartley, Lobster Fishermen, 1940–41, oil on masonite, 29¾ × 40⅞ inches; 75.6 × 103.8 cm

For me, personally, it’s this constant pursuit of how to capture space within the picture plane akin to how space feels within dub music. You feel like you’re moving through it. If you put on headphones, you’re transcended into this lush environment of sound, engulfed in this space. It’s something I’m always in pursuit of within my work.

SM: Well, certainly there’s an incredibly potent sense of space and presence in those late great seascapes of Homer’s, and that physicality carries through to so many artists that followed in his footsteps. For instance, you mention you’re currently living in Lewiston, the birthplace of Maine’s greatest native painter, Marsden Hartley. I’m thinking of his series of breaking wave paintings in which you see a through line from Homer in terms of the boldness of the composition, the physicality, and the sustained moment, if you will—which I see so clearly in some of your works as well, this sort of suspended action.

RBH: Marsden Hartley evokes such a confidence in his paintings, there’s a rawness— the weight behind his application of paint, his bold usage of black lines (fig. 5) that define the forms. There’s this definition, power, and freedom to it, as well as finesse. I’m influenced and fascinated by a painter’s ability to be uncalculated yet precise.

SM: Absolutely, there’s a powerful graphic sense to his compositions. A lot of what you just said I think also applies to an artist like Alex Katz. His work has a boldness that’s immediate and unmistakable in terms of the brushwork and the handling. It’s so quick. If you look at a Katz painting, like his Black Brook series, where you see this rushing water, really graphic, white against black, you see the influence of Homer and Hartley.

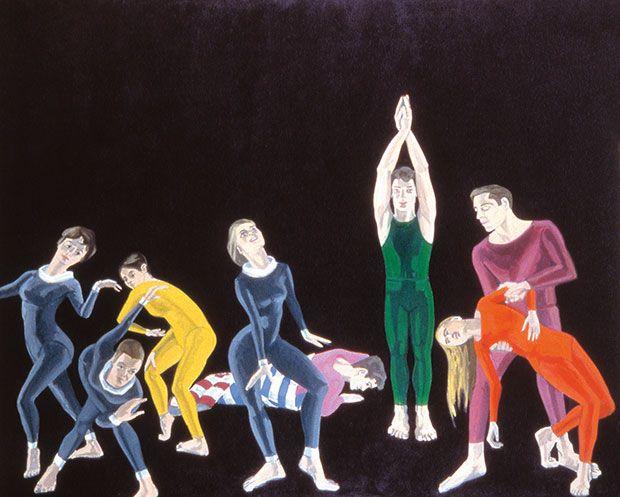

RBH: Yes. In describing his work, Katz often speaks about this sense of immediacy— this idea of the present moment and that the figures are often social but in the contemporary world. I find Katz’s work to be profound in its simplicity. In his piece Paul Taylor Dance Company (fig. 6), the light and color perform so brilliantly over the prominent black ground. I’m always drawn to artists that allow black to perform within their paintings and this is a force that draws me to Hartley and Katz.

My use of this concept is to enroll the Black figure as a stand-in for humanity— that specific way of describing it is part of a thought presented by the scholar Fred Moten, but I pull it from the incredibly poetic way that Arthur Jafa speaks about the idea of the Black figure standing in for humanity.

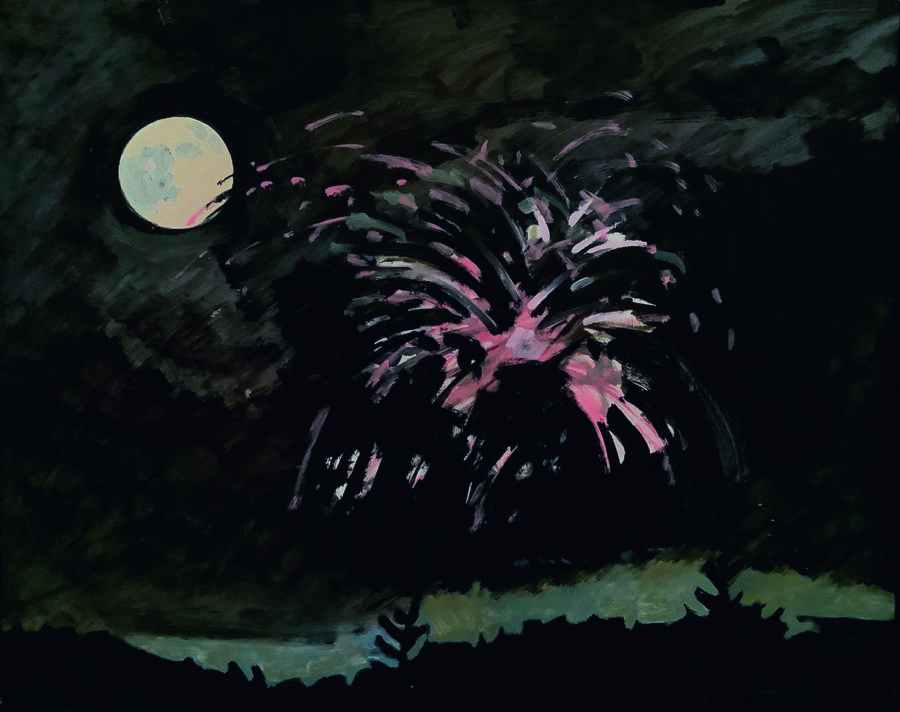

SM: That notion of working from the black ground, I also think of those fabulous night paintings of Lois Dodd. Her paintings of the moon (fig. 7) where there’s these velvety, rich black night skies, and then just pops of color that animate the scene, and uphold that idea of suspended time.

RBH: I love that description, suspended time. Lois’s paintings are amazing in their subtlety. You have this black ground, but then she creates a vibration within that ground by adding greens and purples to the black. She is able to articulate this soft hand and at the same time this dynamic suspension in the way that I perceive Homer expressing—there’s this incredibly free mark-making yet delicately rendered moon all within one breath.

The directness in Lois’s and Katz’s work is something that is very exciting to me, because ultimately I’m trying to get straight to the mark and express my ideas in an unencumbered way. I don’t know how you measure you’ve truly achieved that, but it’s something that I certainly strive for.

SM: Yes, that quality of unvarnished honesty and directness is something I really admire about Lois. I love that quote where she says, “Not everybody seems to see the world that they’re living in, and it’s such a kick, really, seeing things,” that just sums up Lois to me. You can see in her work that she really does get a kick out of observing the world.

RBH: Yes, what a gift. I was really taken by Lois’s paintings of the men’s clinic, which are from the perspective of her New York apartment window. I love how wonderfully abstractly she deals with the shadows of the buildings, and how that creates this three-dimensionality within the paintings. It’s very shape-based, similar to how she describes form in her early cow paintings. There’s a looseness and abstraction to both of them that I am drawn to. I felt really inspired after seeing this work, it was the spark for me to embark on a series from the perspective of the window to my surroundings.

SM: I can see the connection that you’re making with Lois. She often speaks about finding the underlying geometry of the world.

RBH: Yes. It’s an amazing way to look at things and to see—you know what I mean? To really see things first.

SM: Wow, lovely. Well, now I’d like to talk with you about being an artist of color in Maine. We’re not exactly known for our diversity here. I can name on one hand, artists of color who have had a lasting impact on painting in Maine, David Driskell certainly being at the top of that list.

RBH: Yes, it hasn’t been very long since we lost David. Some holes just can’t be filled. Sometimes when you’re talking about the absence of something, once you start really looking you recognize that thing in much more abundance. Now when I think of a community of Black and brown artists in Maine, I think of Indigo Arts Alliance, created by Marcia and Daniel Minter, where David Driskell served as an art advisor and mentor.

For me, it’s amazing to be connected to this community and be associated with such fine painters like David and Daniel. It’s a history and a root that you can’t overlook. David is entwined with these other painters that we’re talking about, which is also really special. Relationships with Lois and Katz, and being at Skowhegan—it’s fantastic because, at the end of the day, in life and art it’s about relationships and community.

Fig. 6 Alex Katz, Paul Taylor Dance Company, 1963–64, oil on canvas, 83⅞ × 96 inches; 213 × 244 cm

Fig. 7 Lois Dodd, Fireworks, 1962, oil on Masonite, 16 × 20 inches; 40.6 × 50.8 cm

Fig. 8 Daniel Minter, A Drift to Now, print, collage, and acrylic on panel, 16 × 24 inches; 40.6 × 61 cm

Fig. 9 Stephen Pace, Untitled, 1965, oil on canvas, 16¼ × 24 inches; 41.3 × 61 cm

SM: Certainly that sense of community is really strong here in Maine. What Daniel and Marcia are creating at Indigo Arts is just fantastic. And, as you say, Lois and Alex and David all met through Skowhegan, but then continued that relationship through so many decades of supporting the larger art community in the state. When you think of six degrees of separation, I always say, “Here in Maine, it never seems more than two.”

I’m thinking back to the first time I met you, which must have been late August 2019, while you were in residence at the Ellis-Beauregard Foundation in Rockland. I remember walking into your studio and thinking, This guy has really found his voice.

RBH: Yes, when I arrived at EBF, I knew that I wanted to break out of where I was as a painter and use this incubation time to land somewhere different, to be able to paint differently than when I came in. Through a lot of experimentation, I arrived at the language of the black ground, specifically in a painting called The Red Umbrella.

SM: Earlier that same summer, you were in residence at the Stephen Pace House in Stonington.

RBH: Yes, near the end of June.

SM: The thing that resonates with me about Stephen Pace and your work is that Pace is a figurative painter who often deals with memory, particularly family memories, and he has this very particular, very idiosyncratic way of rendering figures (fig. 9). I love those works on paper you did in residency there—I’m thinking of Playing Reggae Records at the Pace House. Can you speak to that experience?

RBH: That was an incredible experience. It was so overwhelming and powerful to walk into Stephen Pace’s house in Stonington, Maine. You’re confronted and surrounded by all of this artwork that he created over the years. It’s just breathtaking, walking up to his attic studio that is left as if he just finished painting. Besides the works on paper that I created while in residency there, I also made Swimming in Compton, which I think is a seminal painting. Swimming in Compton was made in that attic studio—it was just an incredibly influential time.

SM: That reminds me of a Katz quote: “Professional painting has to do with finding your insides, and addressing an audience.” You found your insides there.

RBH: Yes.

SM: Now you’re finding your audience.

RBH: Yes, that experience cultivated a visual language, an alphabet—a way of expressing myself that I hope to continue to carry and develop.

SM: You’ve mentioned that one of your favorite painters is Milton Avery, who was a mentor and lifelong friend to Stephen Pace, and I certainly see a relationship in both of your work to how Avery simplifies the figure and composes a scene.

RBH: I aspire to channel a little bit of Avery! I admire his ability to resolve formal concerns within his work. I consider him to be one of our greatest colorists. I also love grappling with these formal issues in addition to layering with narrative and storytelling.

SM: I see a particular connection in your work in your series of seated figures, of figures in repose.

RBH: For me, Avery connects back to Vuillard, Matisse—depicting figures in interiors dealing with everyday life. This idea of the seated figure, the seated listener, is really important to me. It’s one I’ve been wrestling with, in terms of how music has been a major driving force in my life and identity. It’s a medicine, a solution for acclimating myself and situating myself within a space.

SM: Is that seated listener you?

RBH: Maybe—not from a physical, visceral standpoint but from a spiritual presence. It’s the presence of a human being offering you its full attention.

SM: In that sense you’ve brought us back full circle to those silhouetted figures in Homer’s Watching the Breakers that you say you identify with as a way into the work. In a similar way the seated figure—these symbolic figures within your paintings—allow all of us to enter your world.

RBH: Yes, that’s it, that’s the hope, yes.