Pearl Lines, published by Kölnischer Kunstverein, Cologne, 2019.

“I like to play with color and think about the horizon line. I spent a long time trying to get away from the horizon, but now I embrace it. Horizon lines, standing on the boat, peering out, a storm far out there, rough sea, calm sea, and bringing with it a sense of quiet.”

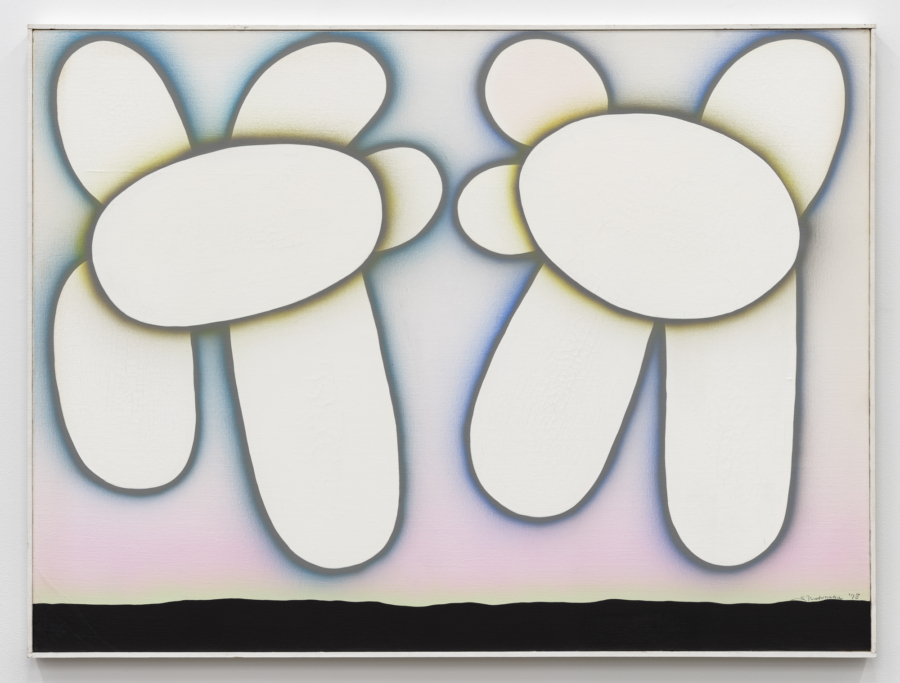

A smudge of blue pigment, operating like the horizon line, separates the white outlines of two heads, which parallel each other, at the center of Walter Price’s Felt soot 12 from 2017. Price spent years on a naval ship where he was not allowed any paint, so he sketched ferociously and often. He remembers the reassurance of the horizon, which we find repeated—perhaps inadvertently so—throughout his most recent paintings. In Felt soot 12, the two heads float near each other with one outlined, level with the viewer, and the other suspended upside down. The Janus-faced entity occupies most of the board, with the flipped head glimpsed as if reflected in water. Half of the painting reads as a reflective surface, an effect that intensifies when one notices two yellow globules of paint—one overtakes the white outline near the top head; its scorching twin is beneath the other. Both read as suns, and yet aside from the double vision of blue lines, yellow orbs, and inverted heads, the worlds above and beneath are different. Price calls the series to which Felt soot 12 belongs the “Brown paintings.” All are done on brown board. Price allows that substrate to function equally with the other colors in the complex framework of the composition. He likes to work in series with two constants: either using the same size support or mining his past work for recognizable imagery. In the top right of Felt soot 12, there is a brick wall, as there often is in Price’s art, rendered in black paint. In Felt soot 12 it is miniaturized, but it is the putative object at the center of the board in Felt soot 7, 2017. The artist uses scraffiti to create the wall. The brick wall is a persistent trope in Price’s work, seen as a pedestal in his recent Trophy series of paintings, 2017–18. Price’s attraction to seriality hails from his training as a printmaker and draftsman.

Aptly oceanic imagery returns in a whirl of biomorphic lines in Felt soot 2, 2017. The artist has purposely left the brush dry in order to capture the membranous skin of water. Five brown posts stand in masses of lines. Similarly, Felt soot 4, 2017, features a blue splotch on the canvas complicated by a not-too-subtly added ultramarine swipe. On the left hovers another yellow-outlined orb speckled with burnt sienna smudges that appear to fall out of its mass. These paintings, with their diminutive size and strong solar focus, would at first glance appear to have some relationship to early American abstraction, to Arthur Dove, for instance, and his many sun paintings, such as Sunrise III, 1936–37; Price, however, sees a closer relationship to Palmer Hayden, the self-trained African American artist. Hayden’s Untitled (Dreamer), 1930, with its floating instruments in a blue swirling sky, as well as the way in which the sleeping body is outlined in white, certainly has a kinship with the way objects and bodies appear to glide across Price’s compositions.

Where Price departs from Dove and Hayden is in his use of words, such as DONTFALLFORIT, all in capitals, partially legible but almost obscured by a long horizontal of blue tape across the bottom, in Felt soot 4. Similarly, returning to Felt Soot 2, one begins to notice words atop the crescendo of wave-like strokes in the painting. These are not fully readable. For Price, the legibility of the text need not matter. The words are culled from sayings that he hears on the way to the studio, words that he saves, things he thinks of while he works. They are, for him, as much formal elements in the paintings as the lines and colors themselves. Yet it’s hard to ignore the feeling that the words are imperatives. DONTFALLFORIT is a brash declaration in Felt soot 4. Price says that he is not addressing an audience, and yet we are forced to contend with his warning in bold capitalized letters.

A part of that declaration is an indication of how much Price is plumbing black culture. DONTFALLFORIT relates to Price’s critique of society in general. He calls these paintings his “Brown paintings” because, yes, they are done on brown paper. Many, like Felt soot 3, 2017, feature brown paint, but the brownness of these works is also related to Price’s insertion of black and brown bodies into abstract painting. Take his titles, for instance: all works in the series are titled Felt soot. The words activate a titular recall of the velvety dark-ness of soot combined with the soft color absorption of felt. We become privy to a cindery duskiness in Felt soot 15, 2017. It is mainly a whirl of washes of black on brown board and horizontal blue lines, the repetition of which is emulative of water. The head, sporting a box haircut, sits on the water, turned away from us. The head is mainly made up of overlapping black circular stickers. Remarkable in their shiny luster, the stickers emphasize how the artist has managed to mimic the tilt of the head out of such imprecise material. Price is attracted to these aberrant materials, for these are his tools for creating content: “I ask myself this, ‘How to take the line, shape, color, tape, sticker, and make something that suggests content?’ Even with metallic paint, painters don’t seem to like it [excluding Sam Gilliam]. I don’t know if a strong painting is a good painting. I want to combine what is obviously strong with what is obviously wrong, to achieve what Hans Hofmann called push-and-pull. I want to make people forget what is wrong with the painting.”

The stickers are Price’s gesture toward wrongness. And so are the words scribbled at the top of Felt soot 15: “Uncle Sammy don’t call me Lucifer.” If the horizon lines, gingerly painted in parallels, are what Price calls his big fundamentals—and here he is referring to Tim Duncan, the basketball player known for delivering the basics—then the stickers, the scrawled sayings, the tape, are all departures from medium specificity, and which clue the viewer in to his interest in wrongness. Wrongness is what allows Price to embrace daring steps in his installations. Take the deep blue color of the walls that he painted for his solo show at the Modern Institute, Glasgow, or the two pieces he has painted in situ at Kölnischer Kunstverein, both featuring Price’s reworking of the paradigmatic heads we find littered throughout his work. In Art alone makes life possible, 2018, the male head is in profile, painted directly on the wall in gold. The title is scribbled and smudged in German, and the head is ringed with a dotted line. There is something belated about the heads, almost like a memory of a past event. The male figure’s flat-top hairdo is no longer in style and is evidence of years past. Hair has a long history in the African American community and Price’s figures, silhouetted or outlined, are identified as black bodies in this way. Even though we are often not privy to their faces, their blackness comes across in subtle gestures. The backs of heads or profiles glance out to the landscape. Price’s work is reminiscent of Eliza Potter’s musing in A Hairdresser’s Experience in High Life. Before setting out in the world on a steamer, she looks at the water: “I was alone in the world—self-exiled from home and friends to be sure—but it was not until we were out some distance upon the rolling waters of the lake, that I realized my isolated condition.”

The dotted outline of a black woman radiates isolation and graces Price’s large mural-sized painting, Perfume. Her hair is partitioned in what are called china bumps or bantu knots, a traditional African American hairstyle. She surveys a blue and brown landscape. The woman’s head is in a one-to-one relationship with the palm tree, which dominates the skyline. According to the artist, his landscapes picture the palm tree as a locus generis of the Caribbean. Although Price grew up in Georgia, where there are no palm trees, he started a series of paintings where he returns to this trope. Indicative of warm weather, of the black diaspora, the palm stands on its own island while on the other landmass sits a blue sofa. Between the palm and the couch, we see double recurring motifs in Price’s oeuvre, which set up a contiguous geography between physically disparate places and cultures.

In the studio, Price speaks about Hofmann, Hayden, Gilliam, Jacob Lawrence, and Norman Lewis. He talks about numerous artists featured in the scattered books on the floor; they confirm his roaming curiosity and investment in the long history of painting. He even makes his own books, bringing the characters in his painting through from page to page, as well as introducing new protagonists. Price spent years on a naval ship, dreaming of doing all of this, but the most fluid words he has found to describe painting come out of basketball. For Price, the goal is always, “Makin’ it funky, keepin’ it fresh.” The paintings are infused with centuries of black visual culture, the history of art, the political conditions that influence all we do; but, more so, Price is grappling with canonical issues of taste. As he unfurls a glittery canvas, he seems excited about what else he will include: sayings, metallics, stickers, and tape. Among the unconventional materials, the convention of the horizon remains, a counter-weight to the “wrongness” that casts the equilibrium of materials asunder. The horizon is a through-line anchoring much of his praxis.

Pearl Lines is available here.

Published on the occasion of

Walter Price

Pearl Lines

Kölnischer Kunstverein

Hahnenstraße 6

50667 Köln

Germany

April 20-June 17, 2018

Edited by Moritz Wesseler

Edition of 1,000