Will Boone: The Highway Hex, published by Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, 2020.

Download as PDF

Will Boone: The Highway Hex is available here

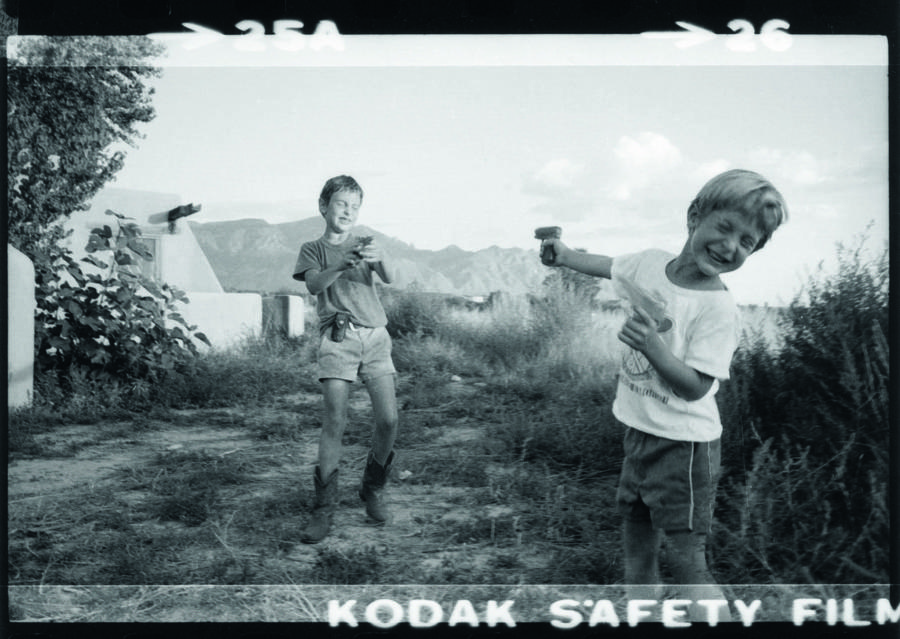

Danny Lyon, detail from The Great Water Gun Fight, 1984.

We were lying down inside a little fiberglass boat, a paltry thing. Even the word boat overstated the facts. This was barely a canoe, sun-frayed, brittle, with a ragged cutout where the outboard motor should have been.

We weren’t in West Texas anymore. We were in a place where you could smell all the plants and the trees and the soil. There was so much green it made me dizzy. Even the birds sounded different, as if they were speaking a foreign language. Why were we there? Where had Bill Ray gone this time? He had dropped us off down in Menard County, where the wet hilly country begins, ten miles from the site of an old fort that had once formed a link on a sturdy chain of forts running all the way from Jacksboro to Eagle Pass, cutting the state roughly in half. As a child I had a vivid picture in my head of white people on the east side of the line facing west, their noses and the barrels of their rifles poking through the last tendrils of a line of trees that ended as abruptly as a picket fence, peeping out across a flat, barren, endless, Comanche-filled prairie that they strangely coveted—upon which, watch as they might, they never saw a single Comanche until it was too late.

Harlan and I had been here for three weeks with a family named McAllister, to whom we were supposed to be related though we had never seen them or heard their names before. The McAllisters had agreed to take responsibility for us even though they had four children of their own, all younger than we were and as wild as feral pigs. Harlan and I kept to ourselves except at suppertime, the only time they asked to see us, presumably to confirm that we were alive and fed, after which we were allowed to go our way again.

In the evening we sat under a massive tree—an oak or maybe a pecan or a cypress, we couldn’t tell. We didn’t know anything about trees; we were flatlanders. We called it the Pussy Tree because it had a prominent oval knot that we thought resembled a woman’s part, though the shape was turned sideways so that it actually looked much more like an eye. On our way back along the river one night past a ruin of chicken pens, we came across the old canoe swallowed up by moonvine. We hacked it out and dragged it up and the next day we bondoed its holes as well as we could—we knew nothing about boats either; until that summer, we had never seen a real river or any body of water bigger than a playa bed after a hard rain.

The Spoon Draw of the San Saba ran five miles from the house. We paddled there one morning looking for nutria with one of Mr. McAllister’s guns, a forty-four he had shown us and had not noticed missing. The pistol was a Belgian copy of a Civil War Colt, but it looked authentically ancient to us. He powdered the paper cartridges for it himself. It was heavy and extremely difficult to load and we were terrified it would explode in our hands, which constituted the basis of its allure. We carried the cartridges and balls and percussion caps sealed in plastic bags because the canoe slowly took on water that we bailed in turns.

Nutria are supposed to be a type of rat, but if so they give the rat a bad name—they’re as big as badgers and they drag their fat hairy chests from the muck of the river like creatures barely evolved. They have long naked tails and foul blood-red incisors that might be intended to strike fear into predators but that also function effectively as target points against dun-colored fur that blends into the underbrush.

Over the course of the morning we brought slaughter to the river, scattering a dozen brindled corpses along the banks. At first I tried shooting from heroic standing positions but the revolver kicked so badly I had to crouch and brace myself; even so the boat listed like a pirate ship in a movie. Harlan steadied the butt flat against the fiberglass, which spalled with each shot.

While we scanned for movement, he sang half-remembered passages of old country songs:

Midway upon my journey

In a forest dark and drear

I lost my way a-walkin’

With my fair girl oh so dear . . .

By noon the wet air was heavy, crowding out breath. Under the full sun, the river shone as brown and opaque as mud and smelled just the lee side of dog shit. The branches of a giant black tree drooped so far over the bank that its branch tips dangled into the water, forming a dark-green shade bower where land and sky seemed to merge, and we let the boat wander in under it and ate damp deviled-ham sandwiches and decided to take turns sleeping, me first in exchange for allowing Harlan to reload the Colt.

But of course he conked out, too. And when he opened his eyes, in his haze, he mistook the shadows of the raveling tree branches at the bottom of the boat for water moccasins that had unwound themselves from up in the tree, as river moccasins are supposed to do, and dropped down into the canoe to kill us.

Danny Lyon, detail from The Great Water Gun Fight, 1984.

Without capsizing the boat Harlan somehow managed to jump to his feet and, fighting just to keep it in his grip, emptied the forty-four cleanly into the hull of the canoe. The six shots passed through the bottom as if through tissue paper, making wet depth-charge thumps under the echo of the report.

Before I knew what was happening—except that Harlan was standing over me, fire leaping from his hands, water gushing up—I sprang and dove clear of the boat. I didn’t feel the river, probably because it was exactly the same temperature as my own body, but everything turned green and then brown and then black and I realized that the bottom of the river was far deeper than I had ever imagined. The lone image in my mind as I made the surface and flailed to shore was a vision of a vast swarm of open-mouthed moccasins like ten thousand medusas wreathing my body just below the water.

Danny Lyon, detail from The Great Water Gun Fight, 1984.

I made the bank and looked back to see Harlan still in the boat, which had somehow managed to remain above the surface even though it was more than half full of water. He stood at one end with the pistol still gripped in both hands, his body veiled by a halo of smoke that drifted away and settled over the river.

“Snakes!” he yelled to me. “I was sure snakes had got in with us!”

Squinting down into the water around him, he let his arms down gently in front of him. He looked at the still-afloat boat and then back at me.

“Sandbar,” he said.

He stepped over the side and picked his way along the spine of the ridge all the way to shore, barely getting his feet wet. When he reached dry land, he lay the Colt on the ground next to me and sat down and with it between us we watched the river go past, thinking about what to do next.