Will Boone: The Highway Hex, published by Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, 2020.

Download as PDF

Will Boone: The Highway Hex is available

I. Exposition

“Texas is just so huge,” the digitized text in Yue Nakayama’s photograph declares. Referencing the second largest state in the United States, boasting a population of nearly thirty million, this statement seems absurdly obvious. Yet it addresses the dialectics of potential and exhaustion that such an immenseness elicits. The hugeness of the landscape, after all, reifies beyond simple statistics. Look to the ceaselessly unfolding topography and characteristically cinematic skies to feel the enormity of the region. The state’s sheer size coupled with an evolving self-awareness of its layered history propagated in equal parts through mandatory Texas history classes as through theme parks with weighted names like Six Flags Over Texas has produced robust traditions of storytelling. Innumerable attempts have been made to capture this complex, contradictory, and charged space. Attendant folklore and mythology abound in prose, song, and visual arts, as there is enough room for a multiplicity of story-crafting traditions to coexist.

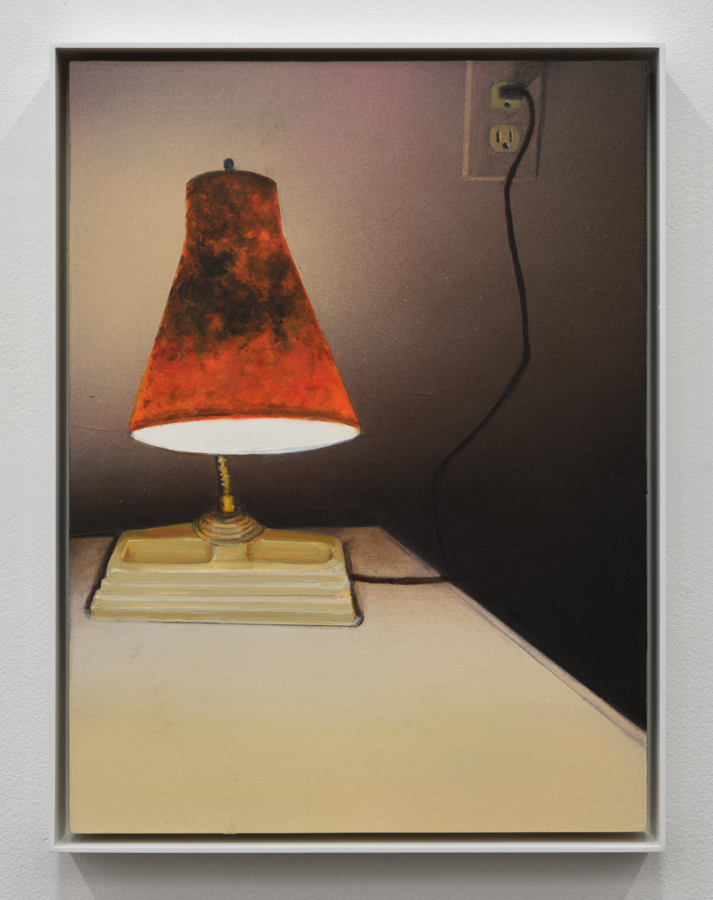

Will Boone, Eyes of Texas, 2018.

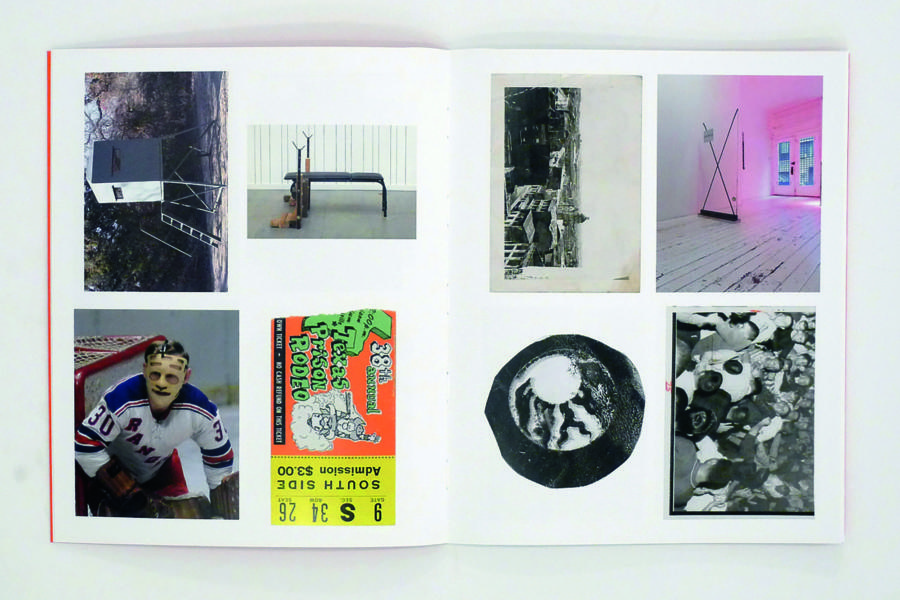

Will Boone’s narrative contribution enriches the lineage of Texan storytellers he finds compelling: Roky Erickson, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Richard Linklater, and Robert Rauschenberg. Boone also actively mines an array of lyrical, countercultural, and textual sources. It would be oversimplistic to say that he is indebted to any particular individuals or precedents his work slips from easy reference into a fertile domain. I initially encountered the artist’s assemblage approach through Prison Rodeo, his small, radiant-red publication. It offers an energizing array of related but unidentified vernacular images alongside reproductions of art installations, all treated with no visual hierarchy. I now know that many of these found images were drawn from the roster of pictures Boone collects and disseminates through such “readers with no words.” Prison Rodeo presents enigmas in place of context, and it precipitated my intrigue in Boone’s multivalent practice. Further investigation made apparent that his expanded art is built on a shared foundation of visual and conceptual concerns. His research-intensive and interdisciplinary method often manifests in dioramas, room-size installations, and playful yet purposeful sculptures that explore a distinctly American mythology. Boone’s signature direct presentation is identifiable despite his resistance to reduction in form or medium, moving fluidly and concurrently between painting, sculpture, installation, and artist’s book.

Will Boone, spread from Prison Rodeo, 2014.

Who has the agency to tell their story, much less to be heard? Who is permitted access to regional legacies? How do memory and trauma compound or conflate the telling of tales? I mourn oral narratives lost to history, alongside concealed stories never shared. My recognition of such loss was borne out of my inhabiting a city marked by persistent erasure both physical and symbolic. Increasingly, I see such sites of destruction as points for rewritings or new tellings, as opportunities to exert control over a narrative and in turn an environment. Boone harnesses and reactivates our region’s heavily mined yet still latent energy via unexpected escape routes and storytelling modes. He and I share an aim to reveal the textures that make our home state singular. Moving away enabled both of us to recognize how our origins defined us. I was raised by storytellers my mother, for one. I remain captivated by her tale of nearly making it big, at least for a girl from small-town North Texas:

In 1970, not many Hollywood movies were shot in Wichita Falls. And yet, the news was out. One of Larry McMurtry’s novels, The Last Picture Show, was being made into a film. Like the book, the setting was Wichita (local lingo for Wichita Falls) and its environs, with a focus on McMurtry’s hometown of Archer City. This news seemed like a miracle to a sixteen- year-old thespian. When my high school drama teacher invited me to audition, I was all in. There was talk in Wichita about Hollywood descending, and not everyone in town shared my enthusiasm. Although McMurtry was a local legend, he was viewed as an eccentric successful, but different from the rest of us. His vintage Mercedes with faux animal skin seat covers was one such manifestation of his nonconforming style. Many Wichitans didn’t think he portrayed our community in a positive light.

A few weeks later, I left my Saturday job at McClurkan’s department store early. My mother insisted that if I drove myself to the audition at the Trade Winds Motor Inn, I needed a chaperone my eleven-year-old sister, Toni. Once at the Trade Winds, I parked my ’Cuda outside, and we were greeted by the male casting director. He seated Toni in the suite’s living room and promptly escorted me to the adjoining bedroom. My antennae were raised immediately, but I tried to keep my cool. Once he closed the bedroom door, the casting director described the scene and asked me to read the part of Charlene. My first line was somewhat alarming: “Eeh! Your hands feel like ice”—Charlene’s reaction as Sonny touched her breasts. I was relieved that we were merely reading lines. The casting director then said that I was a better candidate for the minor role of Marlene, Charlene’s younger sister.

A week later, the director, Peter Bogdanovich, called. My mother was the only one home and wrote down the details concerning my next audition at the same motel. I was permitted to go alone. My reading with Bogdanovich went fairly well. However, I wasn’t convinced that The Last Picture Show was my ideal debut, so I decided to audition Bogdanovich to make sure we shared a similar vision. Bogdanovich explained that the film’s cinematography would be a key element, and that he was going to shoot the film in black and white since this was the best way to capture the mood of the area. He waived his hands at the landscape, which he described as bleak and desolate. He even mentioned our tumbleweeds. I was depressed by Bogdanovich’s description of our surroundings and the quiet angst he sought to convey.

Still from The Last Picture Show, 1971.

Although I didn’t embrace Bogdanovich’s vision, I was disappointed that Marlene’s character was cut. I passed on an offer to be an extra, since I would have to forfeit performing as head majorette for the Rider Raiders marching band. I was present on set several days in Archer City. The pace of filming was slower than I expected, which allowed more time to observe the real-life dramas that unfolded outside the scripted scenes. I was amused to see Bogdanovich and his wife in matching rust suede bell-bottoms.

The citizens of Wichita and the Hollywood crew coexisted harmoniously for a brief period of time. Initially, I saw and talked with cast members at social events in Wichita. I recall my conversations with Timothy Bottoms, his brother Sam (my favorite), and Jeff Bridges, who was unhappy that the only readily available pizza was from Pizza Hut. He said that it tasted like cardboard, but I didn’t know what he meant. The Hollywood outsiders were evicted from the Trade Winds reportedly for “wild” behavior, and according to some rumors, nude swimming parties and were forced to relocate to a remote motel near Sheppard Air Force Base.

It seemed like an eternity before the movie was released. In spite of my dire predictions, The Last Picture Show opened at one of our nicer downtown theaters. I couldn’t wait to see it. On the big screen, the film’s gray landscape enveloped me like a dust storm, and I could barely breathe. As I watched the tumbleweeds dance in the stark black and white, I flashed back to my audition with Bogdanovich and wept.

My family’s fated near misses with Larry McMurtry, one of Texas’s greatest storytellers, did not end with my mother. In 2004 I attended an unconventional youth writing program created and sponsored by McMurtry in Archer City, the same town where The Last Picture Show was filmed thirty-five years earlier. I never met the novelist, as that summer he was intertwined with Hollywood once again, this time filming Brokeback Mountain. Those sweltering summer weeks spent roaming the bust town, save for the McMurtry-owned bookstores dotting the square, informed my sensibilities. I experienced a new mode of Texanness measured, restrained, slow, and distinct from my upbringing in Houston. An unexpected literary capital of Texas held my imagination with all of the vast contradictions contained in one square civic block. Texas never affords an essentialized understanding of the state’s inhabitants, and its thwarting of containment provides endless fodder.

II. Serenade

In his first museum solo show, The Highway Hex, Will Boone has crafted his Texas Serenade a poetic and complex homage to his place of origin. The display of all new work at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH) responds inventively to both the physical site of the gallery and to the institution’s site in Houston, which are linked to Boone’s current home of Los Angeles, California, through 1,500 miles of mostly desolate interstate road. The exhibition features assemblage paintings, large-scale sculptures, a site-specific installation, and Boone’s first long-form video, Sweet Perfume. Together these pieces form their own Gesamtkunstwerk, which is delineated by the deconstructed exterior walls of the gallery space. Borrowing from the visual vocabulary of the stage set, the approach is reminiscent of encountering the exterior of Bruce Nauman’s Left or Standing, Standing or Left Standing (1971) and Kassel Corridor (1972).

Bruce Nauman, Kassel Corridor: Elliptical Space, 1972.

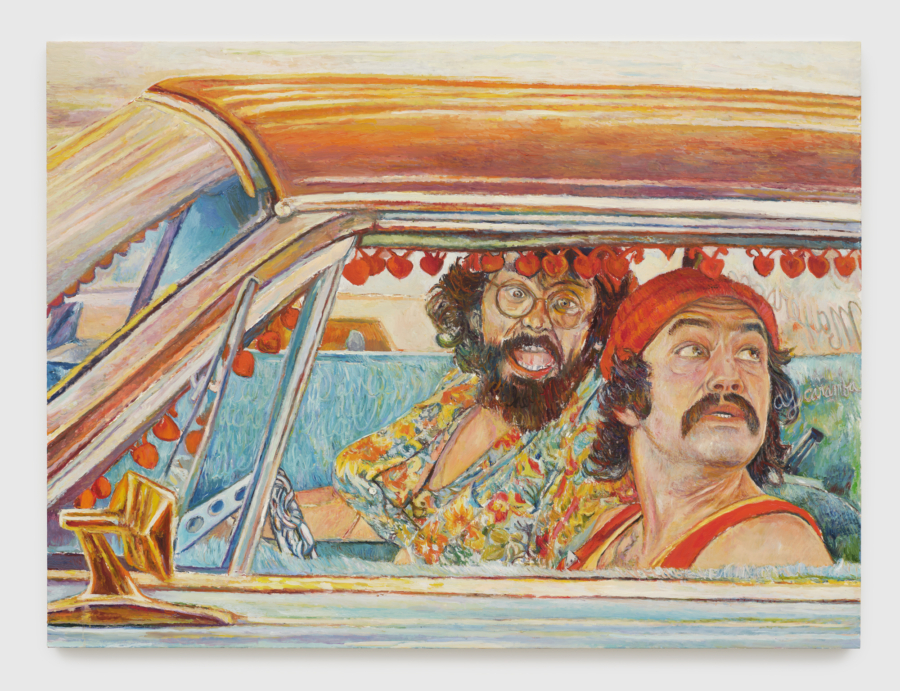

The loose narrative of Sweet Perfume is straightforward: the video orbits around Leatherface, a character lifted from the 1974 horror movie The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, directed by Tobe Hooper. “There’s this beautiful scene where . . . the sun is coming up, and Leatherface is left with nothing to do [after he has no one left to kill]. He begins to dance in the sunshine. I think that’s what he really wants to be doing,” Boone explained. Inspired by this glimpse of humanity and freedom, Boone’s video follows “Face” (as he is now called) outside of his home state of Texas to California, where he exists peacefully on the margins of society. Having left his dark past behind, Face returns to Texas for the first time since his migration west after he is given notice that his family home will be razed imminently. This call originates from a concerned neighbor, voiced by the Texas-born artist, musician, and storyteller Terry Allen, who had a solo exhibition at CAMH in 1975. Boone commented, “The film is about someone dealing with who they are the intersection of who they have been and who they want to be.” With the main character played by the artist’s wife, Stephanie Boone, Sweet Perfume offers humor, metaphysical confusion, and a potentially feminist extension of the cult film. The video’s original soundtrack which Boone wrote and recorded is mesmeric, carrying the film in equal measure as the restrained but witty dialogue.

Sweet Perfume echoes its progenitor. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is linked to the mythical folklore of punk production: the film was made with minimal time and money and features a functional chainsaw instead of a deweaponized prop. In many ways the movie reifies the self-produced appeal of Texas itself. Its attendant rawness and directness is, ultimately, what drew Boone to it. The movie has also attracted fanatics and a huge corpus of fan fiction; Boone enjoys engaging with cultural objects and phenomena that already have an encompassing energy he can harness and redirect.

Sweet Perfume is the center around which the accompanying artworks circulate, demonstrating how Boone’s work cross-pollinates and informs other aspects of his practice. For instance, Boone built numerous sets for Sweet Perfume in his studio, and two of them a pawnshop and a bar have been combined and reproduced in the gallery at CAMH as a single installation, The Melting Cowboy. “I see a direct relationship between the two environments you go to the pawnshop and then afterward, you go to the bar with the money that you get. In the spirit of Houston’s famous lack of zoning laws, . . . I wanted to make a pawnshop you can drink in.”

Fueled by his years based in Los Angeles, Boone considers how objects such as props are imbued with meaning beyond strict functionality. Instead of simply producing props and costumes for the video, the artist created paintings and sculptures that exceed their roles as props, as they now live in the gallery as autonomous works of art. A dialectic emerges between Sweet Perfume and the accompanying artwork, which finds value and identity in relationship to the video while also exerting its own agency. In this way, Boone has subverted traditional objecthood akin to the artist Tom Burr’s ethos on the performativity of seemingly functional objects. For example, the props and objects used in Sweet Perfume’s pawnshop take on the role of conventional character development; Boone utilizes them to define the owner of the shop. The putative distinctions between objects and subjects therefore become blurred, making evident the unceasing interaction between these poles. This mode of production creates a referential relationship between these objects as opposed to a one-to-one translation.

Relatedly, Boone positions Sweet Perfume as a sculptural component of the exhibition, filling the environment and experience of the show with its textured dynamism and vivid color. Relinquishing expectations of a visitor sitting through the fifty-four-minute video, Boone instead revels in the way Sweet Perfume throws color and sound throughout the space, like a glowing television screen visible through your window at night. The Melting Cowboy is similarly commanding and atmospheric. Boone has installed over a Mylar backdrop a combination of found objects and absurd, artist-made sculptures. Mylar similarly was employed as a dynamic and energetic support for lithographs by artists such as James Rosenquist and Rauschenberg, whose Sling Shot series features light-box assemblages with lithographs and screenprints on Mylar and sailcloth panels. Boone also poetically expands the considerations of The Melting Cowboy, likening the installation of its red strings of light to drawing in space.

Robert Rauschenberg, with Per Biorn,Toby Fitch, Harold Hodges, Billy Klüver, and Robert K. Moore, Oracle, 1962–65.

The paintings in the exhibition are a series of large-scale assemblages incorporating found objects and bar top resin. The legibility of these paintings at various distances is gripping, as upon inspection you seemingly witness the undoing, opening, or skinning of an object. Boone refers to these works as “Arterials” given the term’s dual reference to the highway and to the color of stage blood used in horror films: “I was thinking about how it often looks more like hot rod car paint than something that would come from a person. . . . Why would they choose to use that over something more realistic? It’s about the intensity of that color.” The artist has a longstanding investment in color messaging, particularly the story of this decadent and stylized red, which he has called “the color of driving at night.” Many artists have been struck by the same sinister red: Jack Goldstein believed that its vibrancy way a key contributor to the intensity of an experience in his video work and installations, and Rauschenberg embraced it in his Red Paintings (1953–54), following a challenge presented by Josef Albers, his teacher at Black Mountain College. Cadmium red was also employed to great extent by the sculptor Donald Judd, whose work is now synonymous with the sprawling West Texas desert of his adopted hometown of Marfa. Importantly for Boone, William Eggleston also favored extreme colors, notably the intensity of red. In response to his photograph Greenwood, Mississippi (1973), depicting the intersection of white cables on a red ceiling and printed with his famous dye-transfer process, Eggleston noted, “When you look at the dye, it is like red blood that’s wet on the wall.”

Boone’s skills as a colorist also extend to Sweet Perfume. The video oscillates between hyper-saturation and desaturation, feeling effortless despite a clear consideration of visual treatment. Like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Sweet Perfume presents a grainy, pseudodocumentary aesthetic. Used to propel an experience of dread in viewing The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, this approach enables a viewer of Sweet Perfume to feel tied to a specific time and place.

With these new works, Boone demonstrates that, like Texas, he is not afraid to evolve or produce a diversity of content, and his confidence is palpable in the project. However, this art resists consideration in isolation, as it builds off precedents of material and conceptual concerns demonstrated throughout his career. Here Boone returns to themes salient in his artist practice storytelling and unconventional portraiture now seen through shifted perspectives and expanded approaches in different mediums. A commitment to the exploration of what constitutes American visual culture continues to feed his work, as does his impulse to messy conventional distinctions between disciplines. With the exhibition’s treatment of video as sculptures, props as art objects, and abstracted paintings as “portraits of a place,” Boone productively complicates conventional hierarchies and relationships between subject matter, material, and form.

That said, a more conventional focus on narrative representation whether subtly through his assemblage paintings or more concretely in Sweet Perfume signifies a shift in Boone’s mode of production. The loose plot of Sweet Perfume calls to mind Larry McMurtry’s energetic novel All My Friends Are Going to Be Strangers, wherein the young writer Danny Deck also traverses the “mind-warping physical space” from his native Texas to California and back again in a car called “El Chevy.” Both Boone and McMurtry share the ability to recast the subtle textures of familiar landscapes and places, and their explorations of trauma are tempered by a quiet intellectualism and comic infusions. Sweet Perfume envelops humor in an unlikely but convincing manner. Look to the scene in which Boone portrays a televised preacher warning Face of forthcoming doom, and, to our amusement, the enormous cruciform made from two stacked Chevy logos in the background. The video also integrates moments marked by magical realism, such as a cord morphing into a snake, begging the question: is it merely a dream?

III. Myth

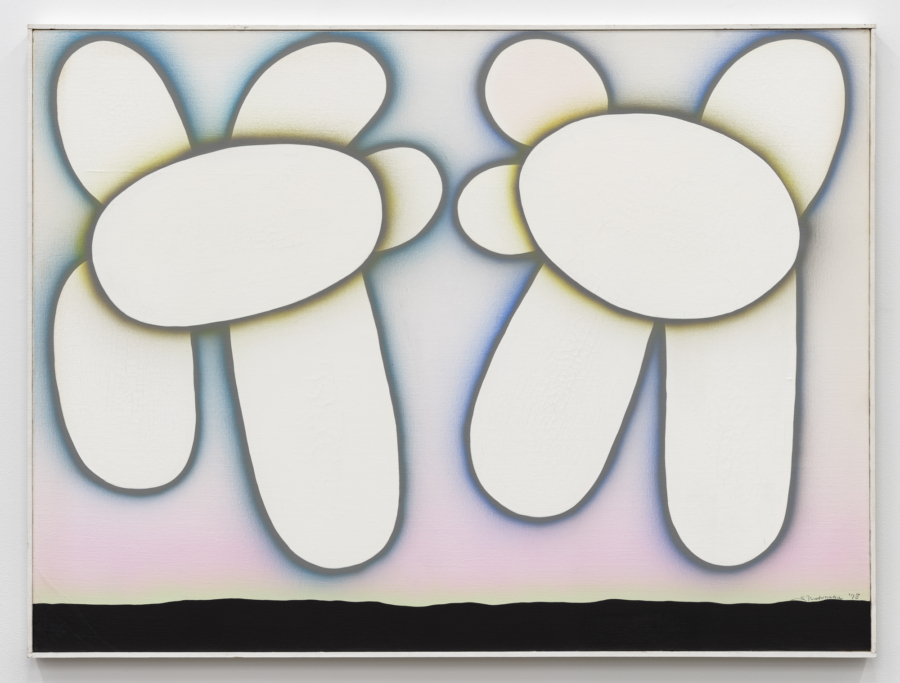

Boone’s work might be framed as centering a “boyish” sensibility, evocative of what Mike Kelley might have made if he had been born in 1982 and in Houston instead of Wayne, Michigan. A singularly reductive consideration of Boone’s work disavows the numerous access points and nuances encompassing it. I am compelled to create a widening in this interpretation. Boone exemplifies a direct yet delicate and restrained style, demonstrated by the intentionally modest number of works included in the exhibition. Furthermore, instead of forcing his preconceived expectations about his work to materialize, he allowed The Highway Hex to evolve organically, sometimes in sharp contrast to the output he had devised initially. “I like to remain open to unexpected possibilities,” he shared. The artist also found new materials to incorporate into The Melting Cowboy during his early days of installation at CAMH, including a toilet from the jail cell of Houston’s downtown courthouse. Boone’s consideration of and response to external parameters also led to the careful citing of the complete environment within the gallery. CAMH is housed within a 1971 Gunnar Birkerts–designed building containing no original right angles. Instead of reacting against CAMH’s idiosyncratic, postmodern exhibition space, Boone leaned in and allowed the gallery to contribute to the possibilities of the show, including the horizontal format of his paintings and the twenty-foot length of The River. He let his work flow with the space, his few but physically and energetically sizable works occupying their own realm with sufficient breathing room.

It is fitting that Boone finds his work in a subterranean zone, yet again. For his contribution to the inaugural Desert X biennial in Coachella Valley, California, in 2017, Boone created the installation Monument, an underground bunker protecting a sitting figure of President Kennedy. The project is part of Boone’s larger effort to wrestle with and expose the ideologies we drive underground. Such psychologically charged spaces mark his other artistic investigations: his 2018 exhibition at David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles, California entitled Garage demonstrates his fascination with those anxieties, activities, dreams, and fantasies we choose to relegate and conceal, here contained within a partially finished, makeshift garage installation situated in the gallery. Parallels with Cady Noland’s work are present. For her 1992 participation in Documenta IX in Kassel, Germany, Noland chose an underground garage to site a three-dimensional version of her lecture-turned-text Towards a Metalanguage of Evil. In his exhibition at CAMH, Boone alludes to isolated activities that typically transpire in a basement, such as model making with The River.

In addition to responding to the challenging specificities of the gallery’s architecture, Boone has produced an exhibition that is place specific, in keeping with the ethos of the arts writer and curator Lucy Lippard. After Lippard’s decentralizing move to New Mexico following decades spent working among New York’s avant-garde milieu, she considered more sincerely not only land art of the American West but also the region’s land use. Although thoughtfully cited in the landscape, how did these immensely scaled interventionist cuts speak to the astrological, human, and ecological histories of these places? “Place-specific art would be an art that reveals new depths of a place to engage the viewer or inhabitant, rather than abstracting that place into generalizations that apply just as well to any other place. . . . The goal of this kind of [place-centered] work would be to turn more people on to where they are, where they came from, where they’re going, to help people see their places with new eyes.”

Boone evinces a similar dialectic. His “multicentered” residences in central Texas and eastern Los Angeles, coupled with his deft treatment of the representation of these sites and a host of places in between, demonstrates what Lippard terms “a serial sensitivity to place.” As she articulated:

Space defines landscape, where space combined with memory defines place. . . . Artists can make the connections visible. They can guide us through sensuous kinesthetic responses to topography, lead us from archeology and land-based social history into alternative relationships to place. They can expose the social agendas that have formed the land, bring out multiple readings of places that mean different things to different people at different times rather than merely reflecting some of their beauty back into the marketplace or the living room.

Through his multifaceted narrative investigations in The Highway Hex, Boone suggests our section of the world is worthy of nuanced exploration. His place specificity continues with his material choices, such as his extensive use of Mylar, a material developed in 1964 by a scientist at NASA for the U.S. space program. Employed throughout the exhibition as a support for various works, the transparent medium both increases the dynamic interplay with light in the show and strengthens a material lineage to Houston.

We often take for granted that landscapes can be composed to create lies. Sweet Perfume effectively makes use of framing devices to expose its own artifice, identifying the image as constructed. In the same vein as the deconstructed exterior walls of The Highway Hex, the fabricated nature of the video and thereby the artifice of our viewing the work, and of viewing in totality is laid bare. We are not manipulated into thinking the video’s context is a priori. Instead, we watch as the camera, itself an intermediary device, sees through mediating structures as diverse but formally unified as chain-link fences, car door windows, and chicken wire.

Continuing a reading of Boone’s work away from the myth of the macho, the artist invites measured vulnerability. His decision to create more intimate and personal work, including his first foray into acting, is particularly revealing. Boone reminded me that the author Harry Crews implored writers to “try to get naked.” Boone’s stripped-down approach has fostered an exhibition that is at once a raw and authentic, yet constructed, manifestation of self.

Will Boone, Monument, 2017.

Boone’s consequential collaboration with his wife, Stephanie Boone, as Face in Sweet Perfume also activates new entry points. This unexpected gendered inversion enables a feminist reading of the video. After all, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is notorious for violently killing female characters with minimal agency. It is worth noting that such strictly misogynist readings of the film are countered in scholarly approaches such as those by Isabel Pinedo, who acknowledges the problematic gender dynamics in the movie while considering narrow interpretations dismissive of the inherent complexities and contradictions of the horror genre. Instead, Pinedo considers such representations of violence against women reflexive of the condition of postmodern society. Boone’s casting of Face to embody the reformed serial killer Leatherface presents a feminist reimagining and reframing of a film characterized by violence against women. Stephanie Boone’s restrained presence is captivating, her piercing blue eyes observing the world from within the confines of her dusty charmeuse mask, fashioned by Boone out of innocuous garden gloves in place of the human flesh of Leatherface’s mask. Face’s visible angst at the loss of a foot during a freak guitar pedal accident reveals just how far he has come from his chainsaw-hacking days, begging the question: why does the rehabilitated Face continue to wear a mask? You can take the monster out of its environment in Texas, but can the monstrousness ever leave the monster? Cady Noland tells us “the psychopath is always wearing a mask except when openly aggressing.”

Boone’s work is rife with representations of masks, from more ominous presentations in Jason Mask (glo) (2014) to softer personifications of seashells or playful homages to iconic Houston locales in Magic Island Head (2019). Masks are utilized to perform, destabilize, and subvert identity constructions. The curator Sarah Darro observed, “As one of the most transformative objects in material culture, a mask can protect, conceal, empower, and free its wearer. Masks are duplicitous they hide one face and reveal another, they horrify and beguile, they disrupt and reconstruct. They bring layered, hybrid figures to life.” Boone’s recurring focus on masking evokes considerations of storytelling, impenetrable presentations of self, and multiplicity of identity. He complicates the visual archetype of the horrific monster in the depiction of a reformed monster continuing to sport his mask itself a symbol of Face’s brutal past, a scarlet A. While Face undermines existing societal expectations in the donning of this seemingly unnecessary vestige, he simultaneously offers more nuanced possibilities to perceive, display, and maneuver complex identities.

IV. Violence

The violence of language consists in its effort to capture the ineffable and, hence, to destroy it, to seize hold of that which must remain elusive for language to operate as a living thing.

—Judith Butler

None of this is to say that Boone’s work is devoid of material or conceptual references to violence. Again akin to sculptures by Cady Noland, Boone’s art contains an implicit violence, presupposing de facto and symbolic violence as omnipresent in our contemporary times, particularly prominent in Texas. Boone’s sculptures interrogate cultural signifiers of Texas and American identity the prototypal bar jukebox, an advertising banner, the man-fortified natural river, livestock brands, and a state trooper uniform. As modern society has lionized violence, indulged in the public spectacle of cruelty, championed unbridled individualism, and fostered separatist ideology, the violence in Boone’s objects is palpable. However, the artist does not connote violence gratuitously; instead his sculptures command a form of brutality through their material frankness, testaments to their fortitude. The works’ confrontation emanates from their shorthand form and simplified material. This epistemological existence can feel threatening, as Boone’s work exerts a detachment in its autonomous presence. The artist reaches into our world, removes an object, and gives it new life. In the process, he respects the integrity of the object’s materiality jackets with zippers intact in Lazy X or old family photographs in Family Tree destabilizing alleged boundaries between visual art hierarchies. In contrast to Surrealist strategy of denaturing a material, Boone allows the materials simply to be. Boone directs and transforms these material concerns, the friction between minimally mediated material and concept energizing his work. In a dialectical opposition to material frankness, Boone’s sense of scale enables an embodied experience of viewing. With his Arterial paintings clocking in a little over six feet high human scale for some the viewing body is implied and recognized. We can envision being part of the installation or looking at the photos affixed to a bar top in the work Family Tree if the piece were reoriented.

Witnesses to violence extend beyond Boone’s material considerations into themes both overt and faint. In The Melting Cowboy, Boone addresses the general public’s association between Texas and violence with objects related to crime, such as laminate tiles from the home of Charles Whitman, who was responsible for the Texas Tower shooting of 1966, alongside a collection of prison shanks. Yet Boone provides nuance in his response to this coupling, speaking to the veneer of violence with his inclusion of numerous velvet paintings of pit bulls misunderstood animals whose behavior might say more about their owners than their intrinsic nature which he likens to Leatherface. Boone also counterbalances this association with the humor of his absurd objects evocative of Meret Oppenheim, such as a shovel with a rubber snake as its armature.

Consider the recurring references to car culture in Boone’s work, including the assisted readymade Resting Place (2019). “You can live in a car. A car is a room. It’s personal space, an amorous atmosphere, like a motel room with an hourly rate and satin sheets.” As in the work of John Chamberlain and Robert Rauschenberg, cars are vital to Boone’s visual vernacular. This is understandable, as the car is a central character in many Texas-related stories. There is Danny Deck’s El Chevy; the stolen cars used as physical and psychological escape vehicles in Randy Kennedy’s Presidio; my own mother’s purple 1970 ’Cuda; and the truck Face swipes to head back to Texas. The car can symbolize a force for freedom, a lifeline for independence, and is frankly the only way to move adroitly across the state’s vastness. The road can become a site of mobility, a place unto itself.

Even this quotidian method of transportation, however, can be considered a violent assertion of the self in a hyper-individualistic society. Lest we forget, the open road has long been hostile toward women as a site of insidious violence.

It should come as no surprise that Carl Andre “saw his work as a road.” The artist Shana Hoehn continues to amass an archive of women’s bodies and traumas across history; one focus is the sexualized and subjugated imagery of women as classic car hood ornaments. Drawing on fast cars coupling in the public imagination with an “all-American” masculinity, Hoehn tracks the history of these small-scale representations of the female form as gendered anxieties. Even the planning and construction of Interstate 10 was marked with violence as its expansion took place on “the fingers of imperialism,”18 including the road’s physical erasure of communities of color and its widespread support partly centered on its ability to evacuate cities under the threat of an atomic bomb.

V. Horizon

Boone’s conceptual and material investigation of transportation, flow, and transformation is palpable in The Highway Hex. In addition to more concrete representations of movement in Face’s journey east, there are quieter allusions, such as the title The Melting Cowboy or the inclusion of a moving blanket and state trooper jacket in The Traitor and Lazy X, respectively. Boone’s jukebox, A Picture of Me (Without You), is also given new life on casters with a cordless power supply owed to its lawnmower battery, thereby enabling it to move enigmatically according to the artist’s whim. Often flowing through a concrete channel reminiscent of the Houston bayou system, the Los Angeles River represented by The River questions how such massive public intervention unknowingly shapes our movements.

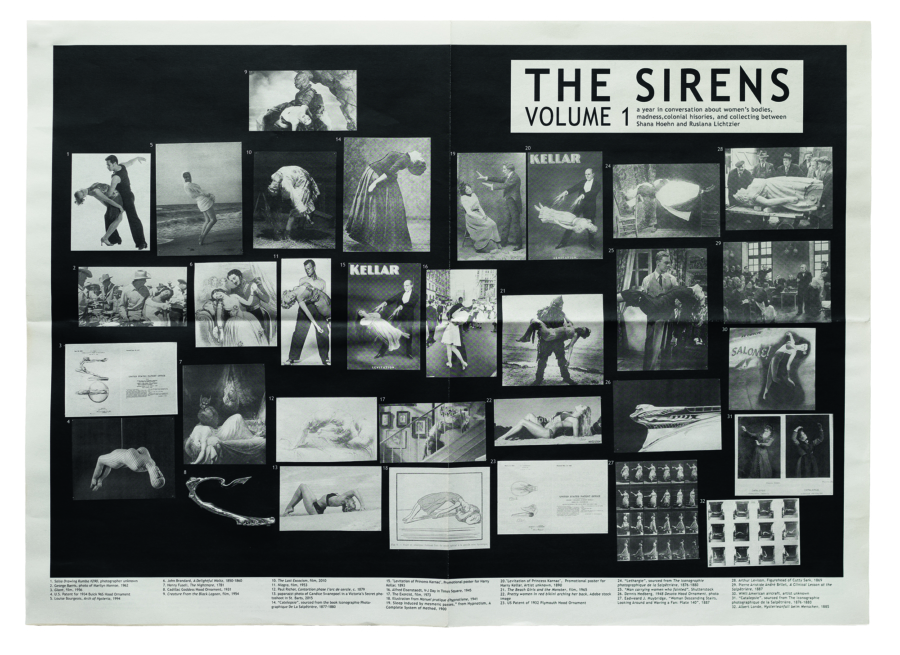

Shana Hoehn, The Sirens, Volume 1, ongoing.

Sweet Perfume illustrates Boone’s preternatural sense for creating visually gripping, idiosyncratic, and moving scenes. Calling to mind the romanticism linked to portraying a frontier space in Valeska Grisebach’s 2017 film Western with its dusty daytimes and vibrant sunsets albeit through a vastly different site and set of eyes Sweet Perfume presents a plot that is, in many ways, secondary to the representation of a huge wild country and residing interpersonal tensions. Time feels suspended and topographical shifts seem slowly to melt, fade, and dissipate under the uncensored sun. Boone focuses on the fragmentary experience, in direct contrast with a monumental narrative arc. We are not given the satisfaction of knowing whether Face’s infamous family house still stands. Ultimately, such revelations are beside the point, as the video provides dimensionality beyond the narrative. Sweet Perfume’s painterly representation of the landscape shown alongside Boone’s new paintings in CAMH’s cavernous exhibition space shows viewers both sides of the horizon, linking the open sky to the subterranean. The horizontal orientation of his elongated paintings allows them to unfold, and then unfold yet again.

At its core, the film honors the complex physical and psychological spaces found between California and Texas. Boone has captured a mode of Americanness that is familiar to many who have traversed this relentless and unyielding landscape. Boone has marked his experience crossing this Western expanse, calling to mind projects such as Joshua Edwards’s Photographs Taken at One-Hour Intervals During a Walk from Galveston Island to the West Texas Town of Marfa (2014) while not as imposing as Dennis Oppenheim’s Identity Stretch (1970–75). Boone’s interdisiplinary folklore envelops us in new sounds, velvety visuals, and an unequivocal place. The artist’s reimaging of extant narratives can be read simultaneously as a self-portrait, a portrait of a geographical region, and a portrait that redirects the possibilities of an infamous movie character. The Highway Hex is a love letter to a complex place meriting nuanced consideration. Surprise and wonder result from the artist’s close and direct observation. He is a facilitator of our viewing, creating the conditions that make it possible for us to encounter a new reading of a well-traversed space. Will Boone’s search for escape routes within previously constructed narratives and histories allows us to wander alongside him, getting lost in the folds and our deviations from expectations.