Online Viewing Room

Gertrude Abercrombie

October 28–October 31, 2020

Art Basel

Online Viewing Room

Gertrude Abercrombie

October 28–October 31, 2020

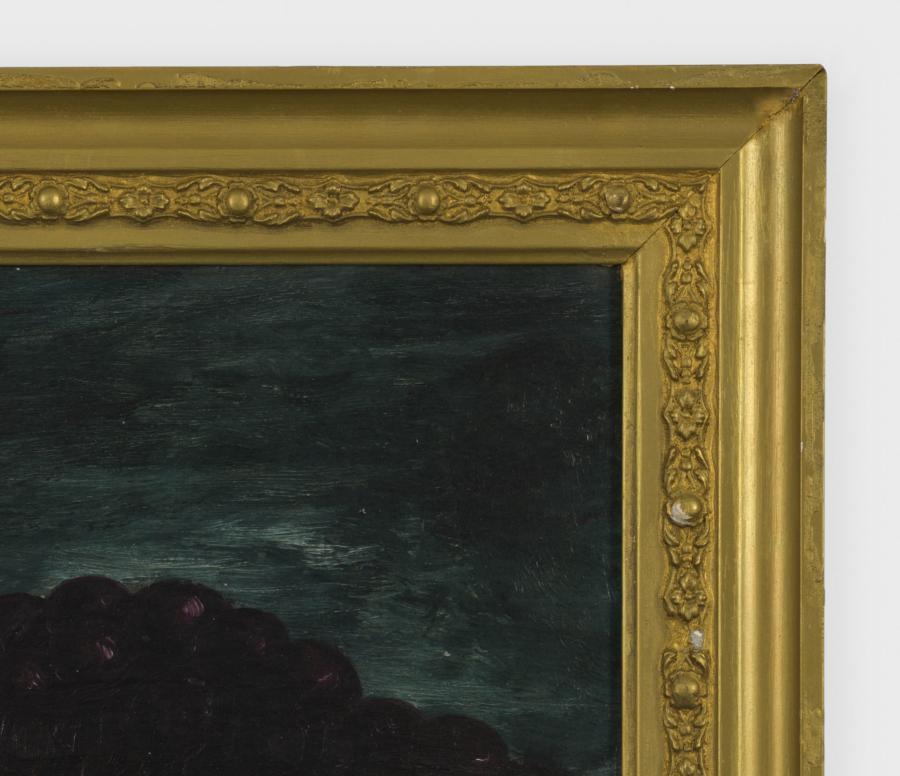

Countess Nerona #3, 1951 (detail)

Fruit Compote, 1938 (detail)

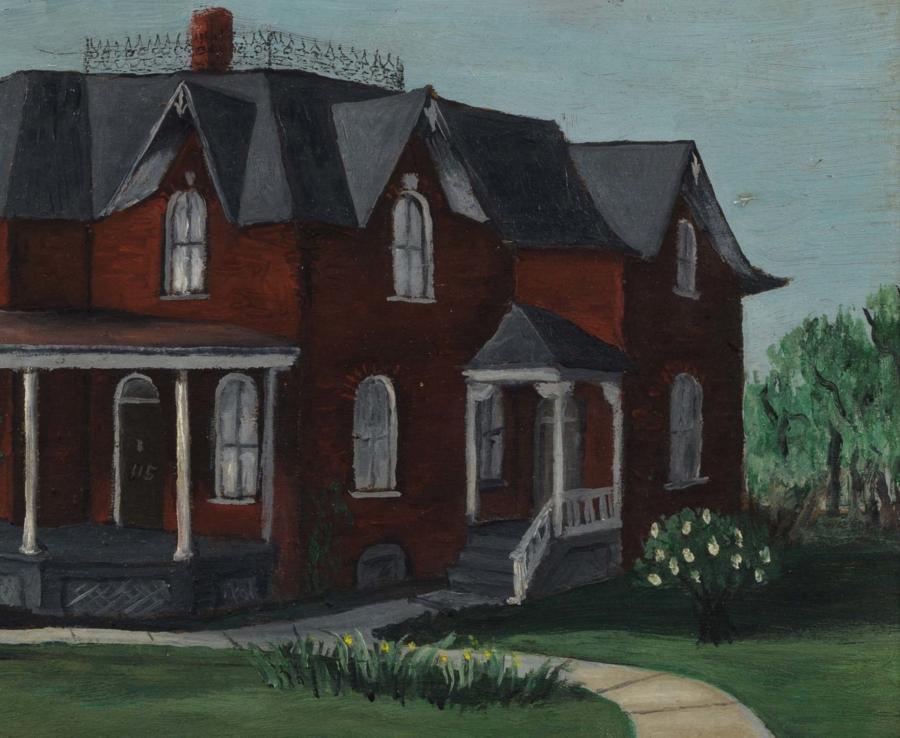

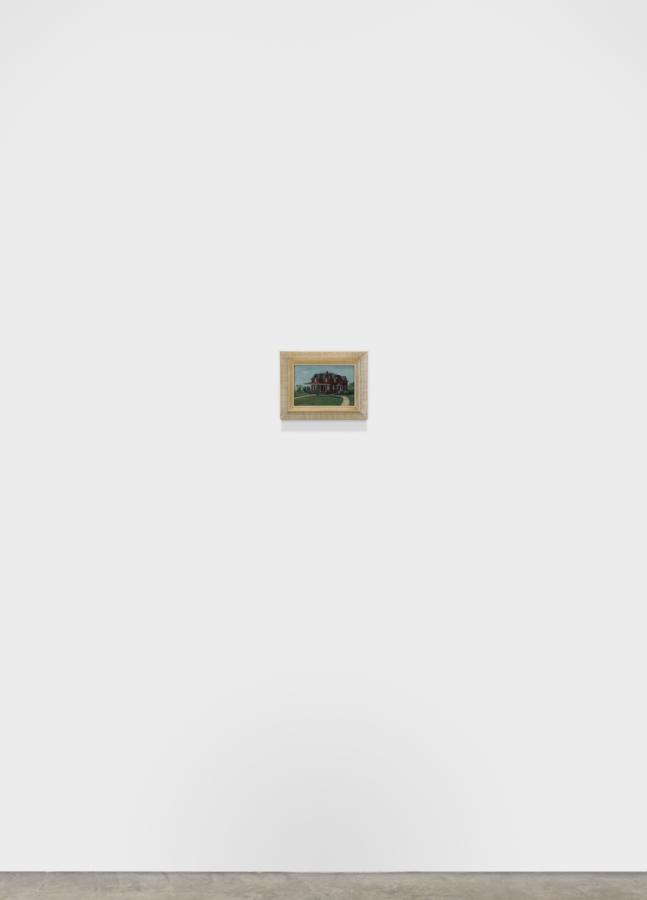

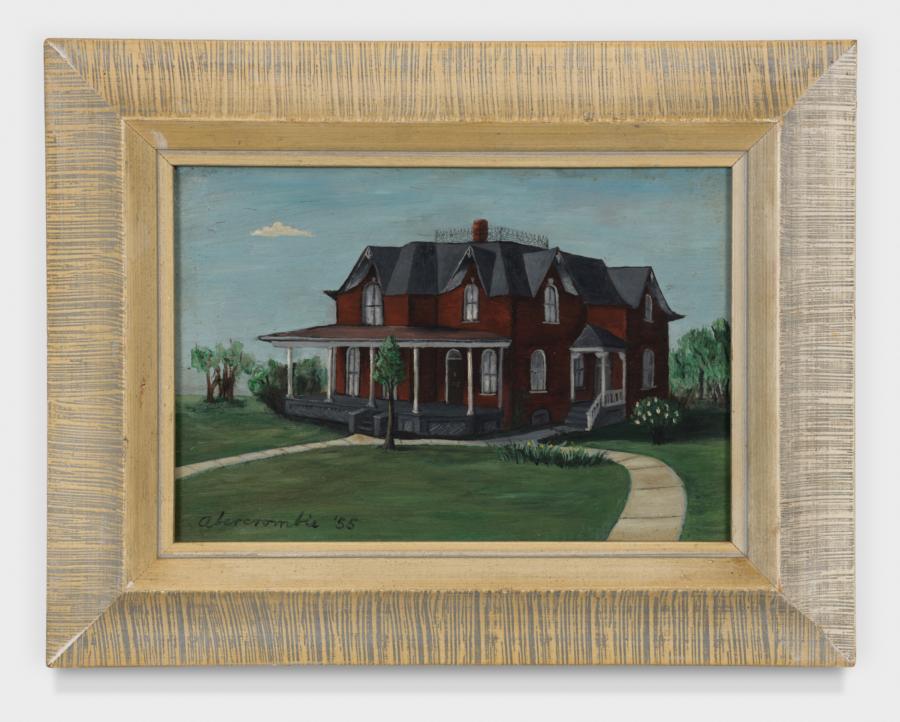

Small Aledo House, 1955 (detail)

White Cat and Red Carnations, 1941 (detail)

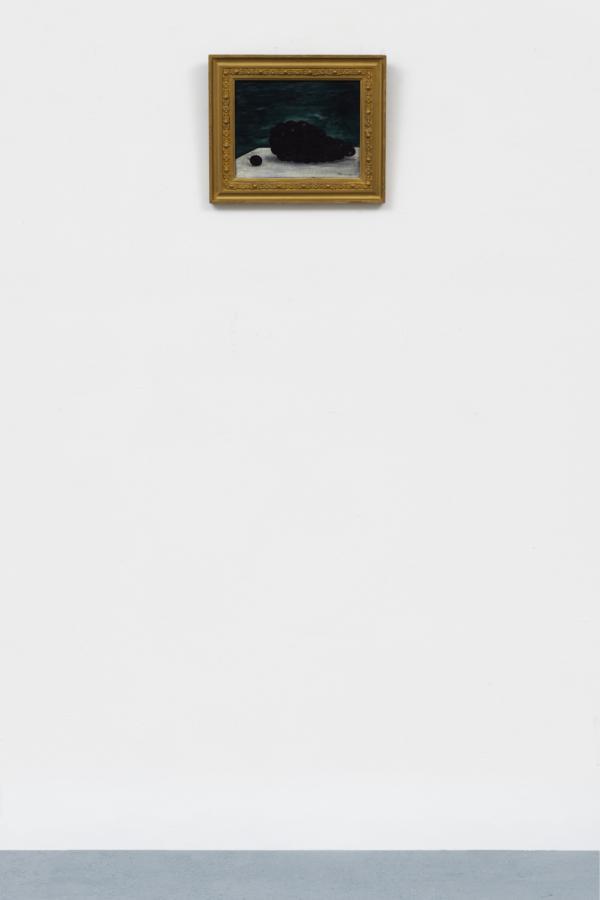

Untitled, 1959 (detail)

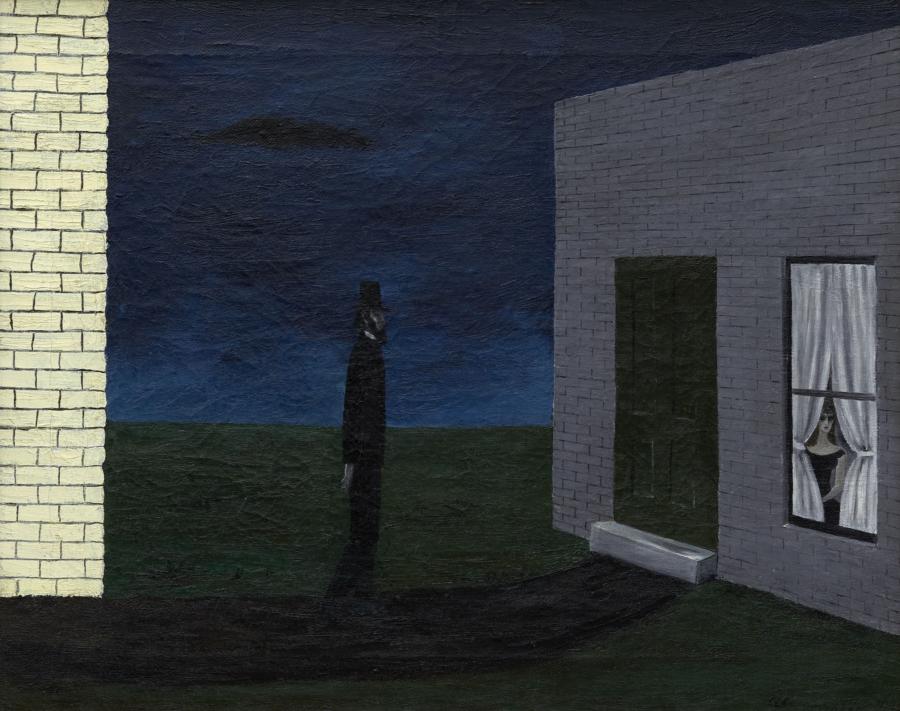

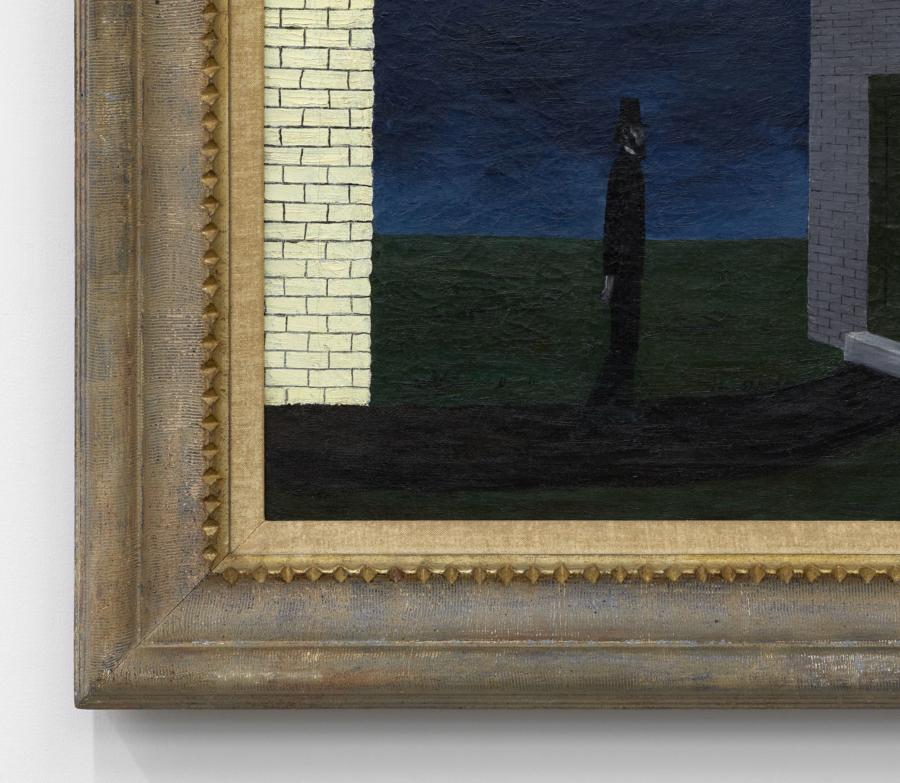

The Visit, 1944 (detail)

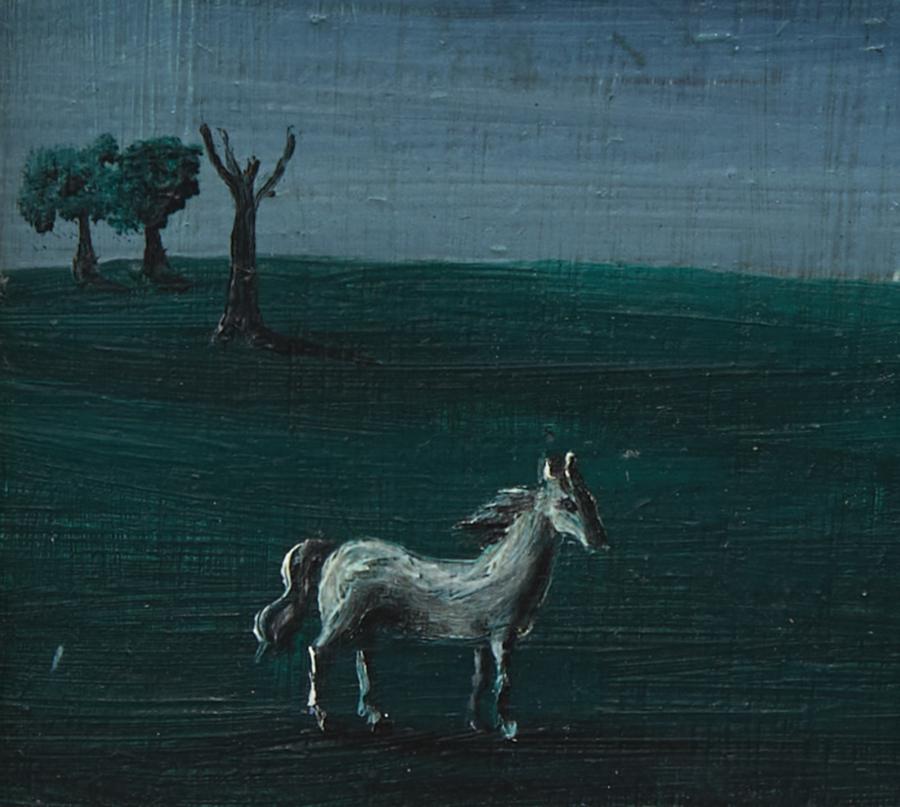

White Horse, 1939 (detail)

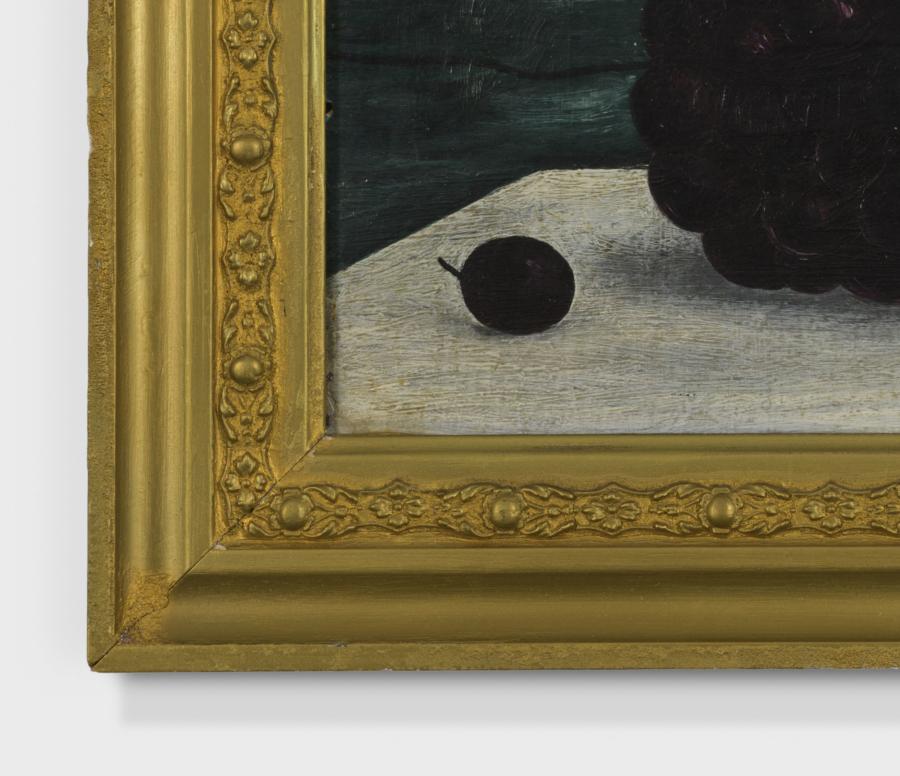

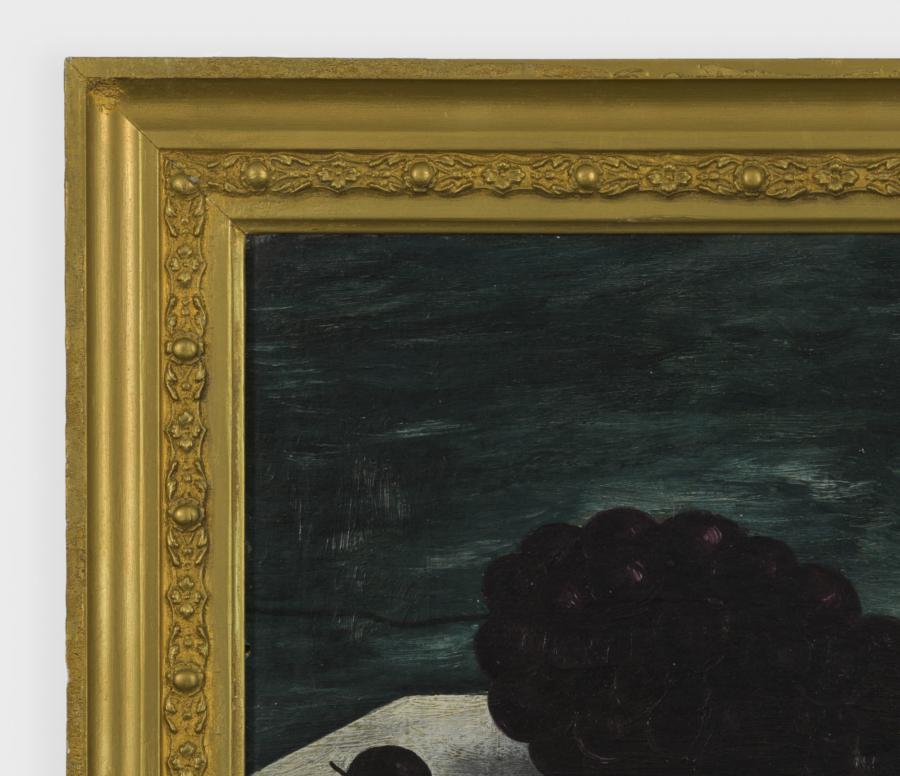

Grapes, 1940 (detail)

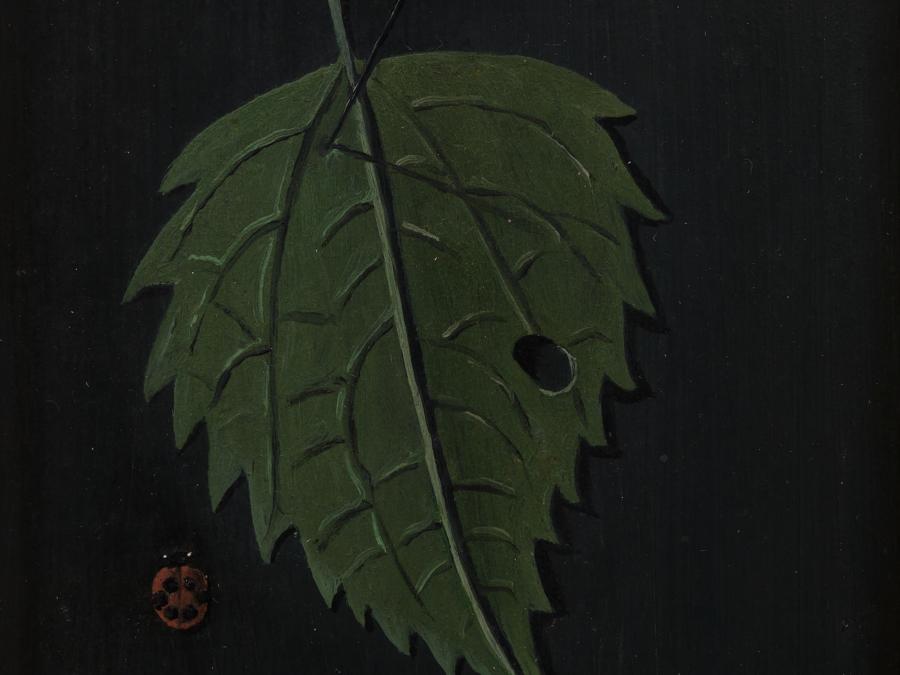

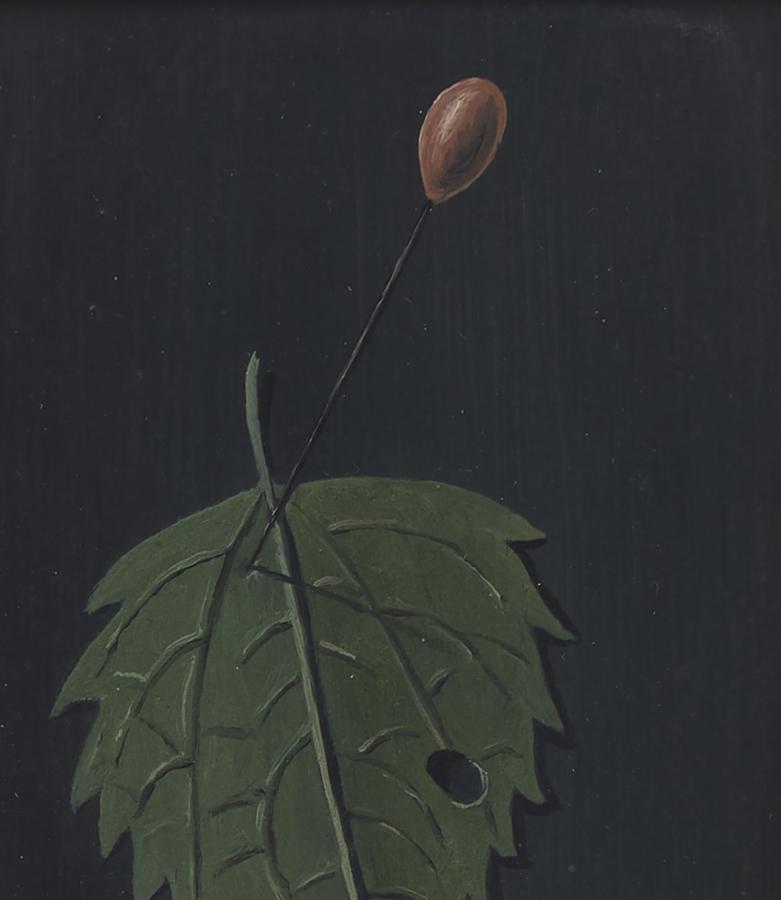

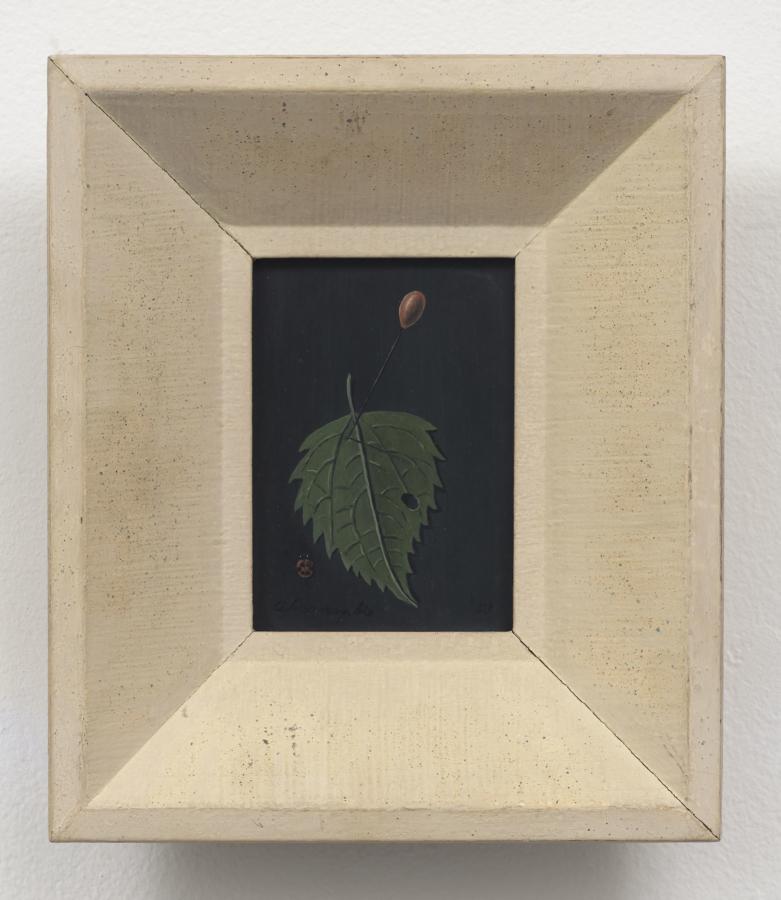

Leaf with Pin and Ladybug, 1953 (detail)

by Susan WeiningerGERTRUDE ABERCROMBIE

by Susan Weininger

Gertrude Abercrombie, who lived and worked in Chicago all of her life, transformed her inner, often unconscious, life into works of great mystery, resonance and power. Working in Chicago beginning in the 1930s, outside the major art centers of the world, gave her the freedom to create without having to adhere to the pressure of art world norms. As a woman and a Midwesterner during the interwar period, she was doubly marginalized. She was able to turn this into an advantage.

She memorably said “It is always myself that I paint, but not actually, because I don’t look that good or cute.” And although none of the paintings in this exhibit are explicitly self-portraits, each of them embodies her in various ways.

Her earliest work consisted of portraits, both self-portraits and those of friends and family members; still life paintings; and landscapes based on the environment in the far western Illinois town of Aledo where she spent many happy summers with her extended family. As an only child, visits to Aledo represented happiness, providing her with community and freedom. White Horse (1939), a small image of verdant rolling hills with a horse in the foreground is one of those. Yet even in this tiny landscape we see some of the things that become part of her repertoire of objects—the barren rocks and leafless trees—that give the landscape a feeling of solitude and austerity that are so common to her work. This is in contrast to the often glorified images of heartland landscapes so common during the Depression, adhering to the mandate to paint the “American Scene,” an explicit expectation of the government supported arts programs of the Depression, in which Abercrombie participated from 1934 on. She was just beginning her career at the time and the regular salary provided by the Illinois Art Project validated her as an artist and enabled her to move from her parents’ home into her own apartment in a building occupied by many artists and writers who became her new community. The 1955 Small Aledo House, a depiction of her grandparents’ home in Aledo, is an image she returned to a number of times in her career, again bringing to mind the positive feelings

associated with her extended family.

In the two still life paintings from her early period, we see a bunch of grapes, something that Abercrombie repeatedly painted, both in paintings like these (Grapes, 1940; Fruit Compote, 1938) and as decoration on a hat she depicts in other still life images or wears herself in self- portraits. The pedestal server on which the fruit is arranged, an object she herself owned, appears in other paintings. In White Cat and Red Carnations (1941), depicting a cat and an ironstone pitcher holding carnations, often repeated in her work, are personally meaningful to the artist in even more important ways. Cats were very important in Abercrombie’s life, and her household always had a number of them, the pitcher was her own, and the carnation was “the national flower of Gertrude’s creation,” according to her friend, writer Wendell Wilcox. These objects are personal emblems that stand in for herself, so even when she is not visible, she is present in her work.

In The Visit (1944), a rare image including a male figure (Abraham Lincoln, who appears in a number of her paintings) who approaches a simple brick block house with Abercrombie peeking out the window. As a proud midwestern Illinois resident, Abraham Lincoln had great symbolic value and with the exception of a few images which include her husbands, he is the only man to make an appearance in her work. Again, the mystery is enhanced by the presence of this 19 th century icon in her work.

Many austere rooms, modeled after Abercrombie’s first apartment, appear in Abercrombie’s work; these deceptively simple rooms are painted with infinite variety and different arrangements of the personal emblems seen in her other work. The austere rooms clearly reflect Abercrombie’s internal feelings of emptiness, countered by her powerful personae of witch or queen (in life and art). In Countess Nerona #3 (1955), it is a character from a Wilkie Collins novel that Abercrombie loved, who is represented. A stand in for the artist herself, she is reclining on a chaise modeled on one owned by Abercrombie, accompanied by a large white cat in a pristine interior. The picture on the wall (the picture in a picture was frequently used by Abercrombie) is a landscape similar to the one in White Horse, with a leafless tree, black bottomed cloud and sliver of moon, all elements personal to the artist. The picture extends the meaning of the primary scene, complicating this seemingly simple image.

In the early 1950s, Abercrombie focused on creating images with great technical fluency and detail, such as Leaf with Pin and Ladybug (1953), although she found it difficult to sustain the commitment to attentiveness on this level. The elements in this jewel-like composition begin to appear in her work more frequently at this time.

The work in this small exhibit contains examples of a number of Abercrombie’s major themes, and is a nice introduction to the engaging, witty, deceptively simple work of an artist who translated her internal conflicts into works that speak powerfully.

Countess Nerona #3, 1951 (detail)

Countess Nerona #3, 1951 (detail)

Countess Nerona #3, 1951 (detail)

Countess Nerona #3, 1951 (detail)

Countess Nerona #3, 1951

Oil on masonite

4½ × 7 inches; 11.4 × 17.8 cm

9 × 11½ inches; 22.9 × 29.2 cm (framed)

GA-51-003

Countess Nerona #3, 1951

Oil on masonite

4½ × 7 inches; 11.4 × 17.8 cm

9 × 11½ inches; 22.9 × 29.2 cm (framed)

GA-51-003

The Visit, 1944 (detail)

The Visit, 1944 (detail)

The Visit, 1944 (detail)

The Visit, 1944 (detail)

The Visit, 1944

Oil on canvas

15 × 20 inches; 38.1 × 50.8 cm

23 × 27 1⁄2 inches; 58.4 × 69.9 cm (framed)

GA-44-002

The Visit, 1944

Oil on canvas

15 × 20 inches; 38.1 × 50.8 cm

23 × 27 1⁄2 inches; 58.4 × 69.9 cm (framed)

GA-44-002

Untitled, 1959 (detail)

Untitled, 1959 (detail)

Untitled, 1959 (detail)

Untitled, 1959 (detail)

Untitled, 1959

Oil on unstretched canvas mounted on paperboard

9 × 12 3⁄4 inches; 22.86 × 32.38 cm

11 1⁄2 × 15 1⁄4 inches; 29.21 × 38.73 cm (framed)

GA-59-002

Untitled, 1959

Oil on unstretched canvas mounted on paperboard

9 × 12 3⁄4 inches; 22.86 × 32.38 cm

11 1⁄2 × 15 1⁄4 inches; 29.21 × 38.73 cm (framed)

GA-59-002

White Cat and Red Carnations, 1941 (detail)

White Cat and Red Carnations, 1941 (detail)

White Cat and Red Carnations, 1941 (detail)

White Cat and Red Carnations, 1941 (detail)

White Cat and Red Carnations, 1941

Oil on canvas

16 × 20 inches; 40.6 × 50.8 cm

24 1⁄4 × 28 1⁄4 inches; 61.6 × 71.75 cm (framed)

GA-41-003

White Cat and Red Carnations, 1941

Oil on canvas

16 × 20 inches; 40.6 × 50.8 cm

24 1⁄4 × 28 1⁄4 inches; 61.6 × 71.75 cm (framed)

GA-41-003

White Horse, 1939 (detail)

White Horse, 1939 (detail)

White Horse, 1939 (detail)

White Horse, 1939 (detail)

White Horse, 1939

Oil on masonite

2 1⁄2 × 3 3⁄8 inches; 20 × 22 cm

8 × 8 5⁄8 inches; 20.32 × 21.91 cm (framed)

GA-39-005

White Horse, 1939

Oil on masonite

2 1⁄2 × 3 3⁄8 inches; 20 × 22 cm

8 × 8 5⁄8 inches; 20.32 × 21.91 cm (framed)

GA-39-005

Leaf with Pin and Ladybug, 1953 (detail)

Leaf with Pin and Ladybug, 1953 (detail)

Leaf with Pin and Ladybug, 1953 (detail)

Leaf with Pin and Ladybug, 1953 (detail)

Leaf with Pin and Ladybug, 1953 (detail)

Leaf with Pin and Ladybug, 1953

Oil on masonite

4 1⁄4 × 3 1⁄8 inches ; 10.8 × 8 cm

8 1⁄2 × 7 inches; 21.59 × 17.78 cm (framed)

GA-53-002

Leaf with Pin and Ladybug, 1953

Oil on masonite

4 1⁄4 × 3 1⁄8 inches ; 10.8 × 8 cm

8 1⁄2 × 7 inches; 21.59 × 17.78 cm (framed)

GA-53-002

Fruit Compote, 1938 (detail)

Fruit Compote, 1938 (detail)

Fruit Compote, 1938 (detail)

Fruit Compote, 1938 (detail)

Fruit Compote, 1938 (detail)

Fruit Compote, 1938

Oil on board

12 × 10 inches; 30.5 × 25.4 cm

13 1⁄4 × 11 1⁄2 inches; 33.66 × 29.2 cm (framed)

GA-38-002

Fruit Compote, 1938

Oil on board

12 × 10 inches; 30.5 × 25.4 cm

13 1⁄4 × 11 1⁄2 inches; 33.66 × 29.2 cm (framed)

GA-38-002

Small Aledo House, 1955 (detail)

Small Aledo House, 1955 (detail)

Small Aledo House, 1955 (detail)

Small Aledo House, 1955 (detail)

Small Aledo House, 1955

Oil on board

5 × 7 inches; 12.7 × 17.8 cm

8 × 10 inches; 20.3 × 25.4 cm (framed)

GA-55-005

Small Aledo House, 1955

Oil on board

5 × 7 inches; 12.7 × 17.8 cm

8 × 10 inches; 20.3 × 25.4 cm (framed)

GA-55-005

Grapes, 1940 (detail)

Grapes, 1940 (detail)

Grapes, 1940 (detail)

Grapes, 1940 (detail)

Grapes, 1940 (detail)

Grapes, 1940

Oil on panel

8 1⁄4 × 10 inches; 21 × 25.4 cm

11 1⁄2 × 13 1⁄2 inches; 29.2 × 34.3 cm (framed)

GA-40-007

Grapes, 1940

Oil on panel

8 1⁄4 × 10 inches; 21 × 25.4 cm

11 1⁄2 × 13 1⁄2 inches; 29.2 × 34.3 cm (framed)

GA-40-007