GOUACHES

DIKE BLAIR

GOUACHES

SIX NOTES ON COLOR

JIM LEWIS

SIX NOTES ON COLOR

Not long ago, I inadvertently but happily provoked a long discussion on social media by asking, because I had used the expression in a novel, whether there was such a thing as grey light. This, it turned out, is a more ambiguous question than it looks, but after numerous clarifications, it came down to something like: Is there a kind of bulb, or a gel that can be placed over a white bulb, which, when shined on a white sheet of paper, makes it look grey? Many people weighed in on this, philosophers, scientists, artists, and in time an answer emerged, which was that no one was quite sure. It seems, on the one hand, that what we would think of as grey light is merely a dimmer white light. But if I put blue bulbs in my fixtures at home, my white couch will take on a blue tone; if I turn down the regular white bulbs, it doesn’t look grey, it merely looks a bit darker. And yet the midtones of a black and white movie are clearly and irrefutable grey; and yet, again, that may be an illusion created by the neighboring whites and blacks. Suppose I were to partially expose a frame of black and white film, then, develop it normally, and project it. Will you say, “There it is: grey light”? Or will it just look like an especially weak white? No less a figure than Wittgenstein discusses this, in his “Remarks on Color” (Bemerkungen Über Die Farben), where he asks “Why is there no brown nor grey light? Is there no white light either? A luminous body can appear white but neither brown nor grey. Why can’t we imagine a grey hot?” — Well, can we? These kinds of questions are philosophical curiosities, and seem to belong to that real but seldom seen category of statement defined by Kant as the “synthetic a priori”, that is, things which are to be reckoned true or false, not through pure cognition (like mathematical truths), or by observing evidence (like, say, evolution), but somehow in between.

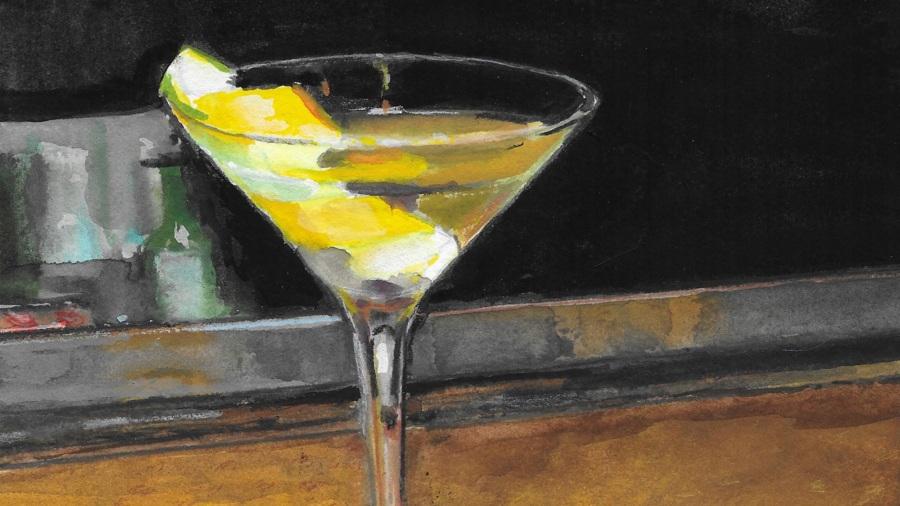

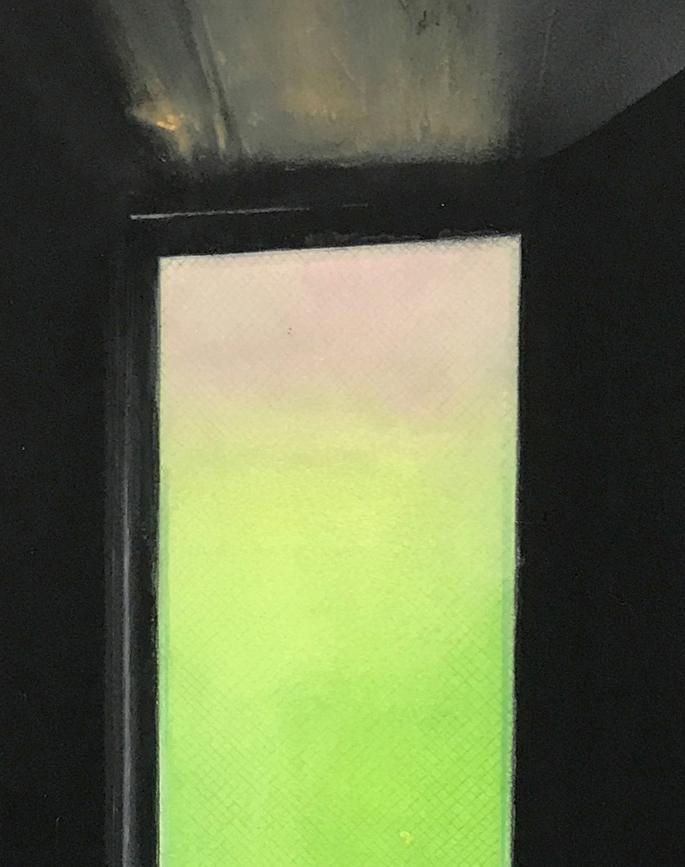

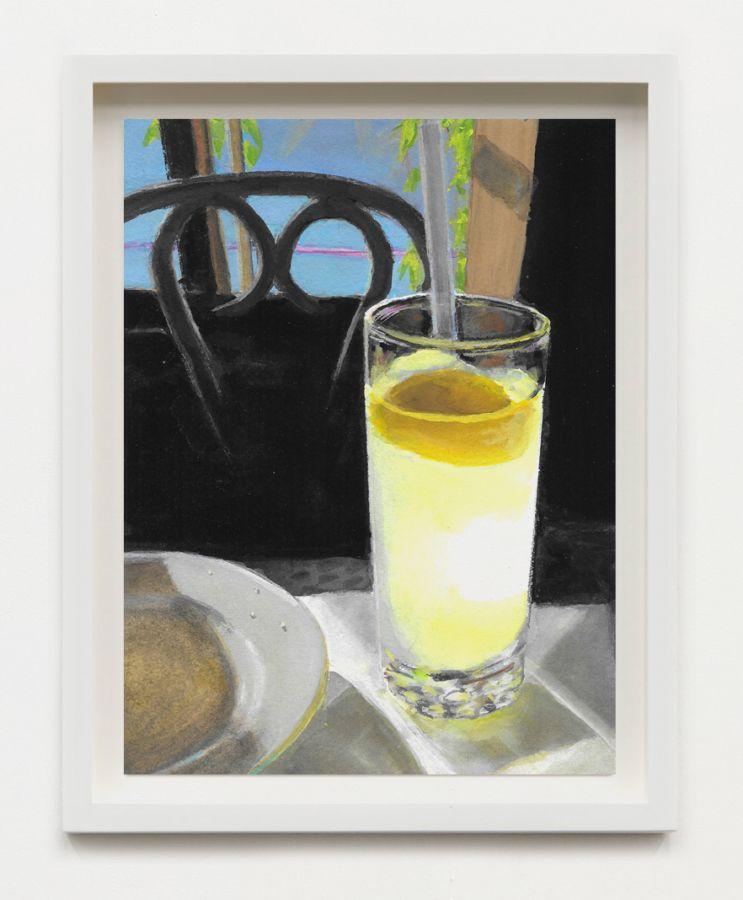

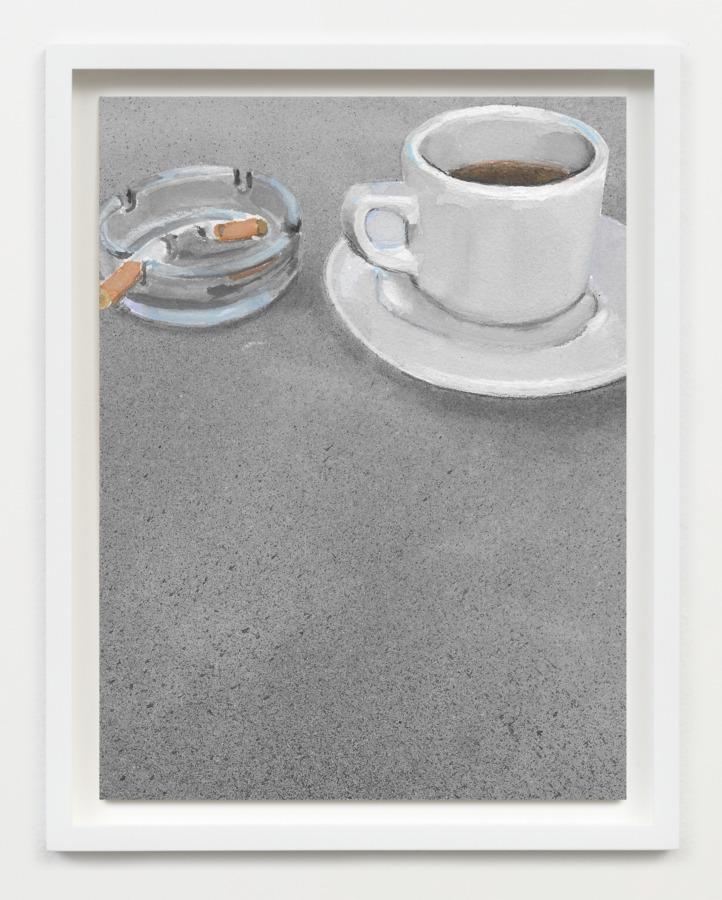

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

20 × 15 inches; 51 × 30 cm (unframed)

21 1⁄2 × 16 1⁄2 inches; 54.61 × 41.91 cm (framed)

DB-20-012

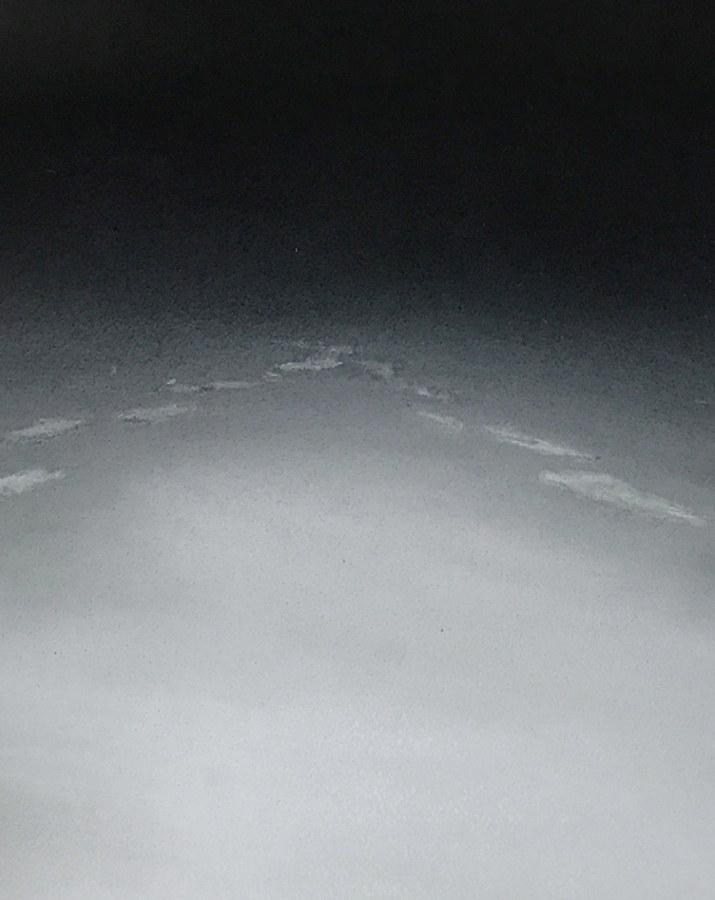

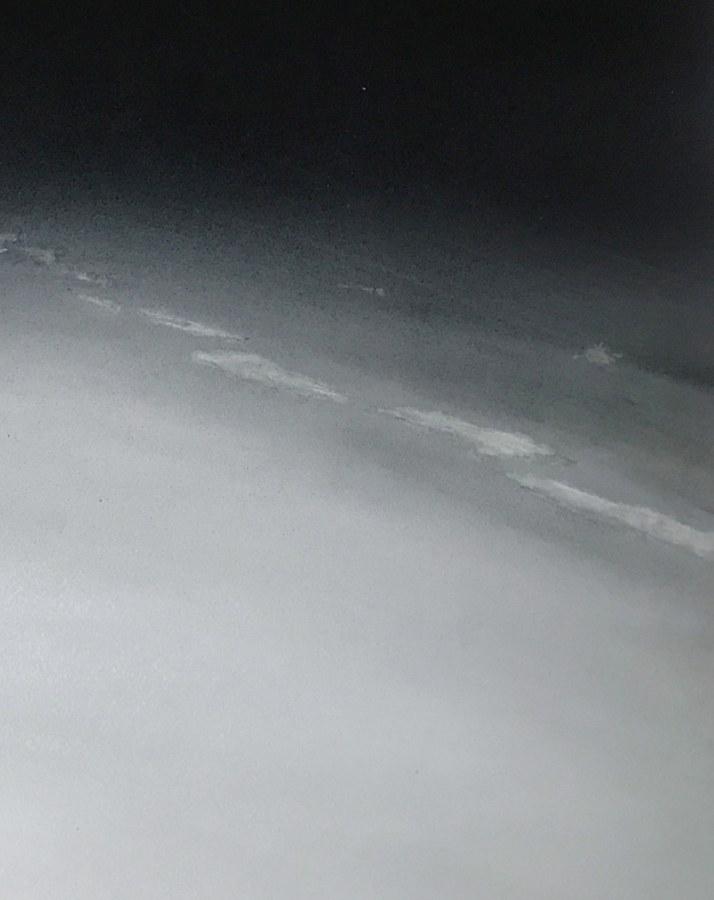

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

20 × 15 inches; 51 × 30 cm (unframed)

21 1⁄2 × 16 1⁄2 inches; 54.61 × 41.91 cm (framed)

DB-20-012

Another example of a potentially synthetic a priori statement: Can there be a reddish-green?

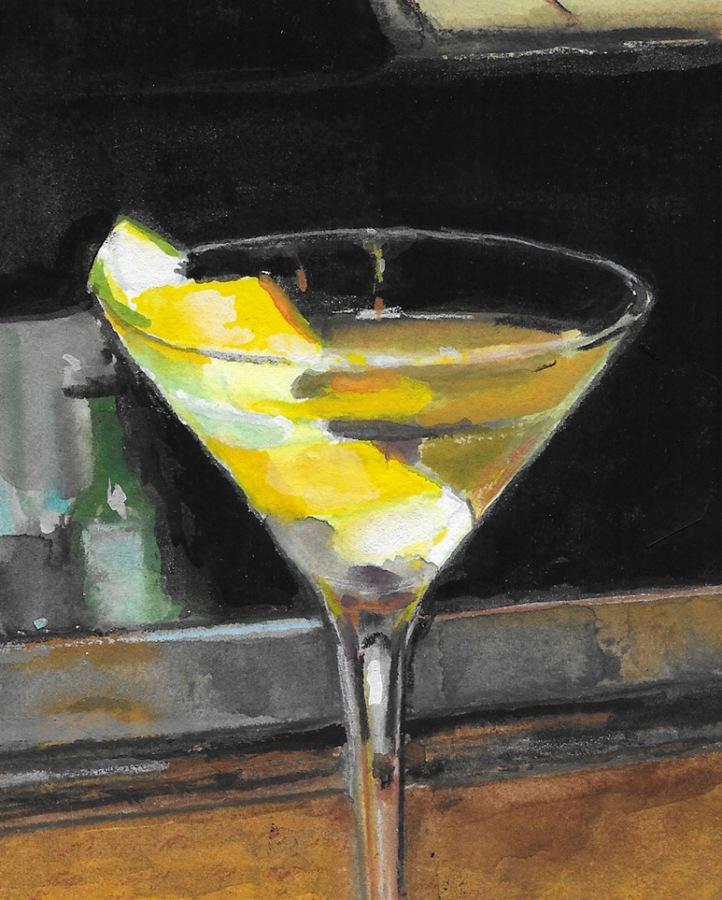

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

10 × 7 1⁄2 inches; 25.4 × 19.05 cm (unframed)

11 1⁄2 × 9 inches; 29.21 × 22.86 cm (framed)

DB-20-020

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

10 × 7 1⁄2 inches; 25.4 × 19.05 cm (unframed)

11 1⁄2 × 9 inches; 29.21 × 22.86 cm (framed)

DB-20-020

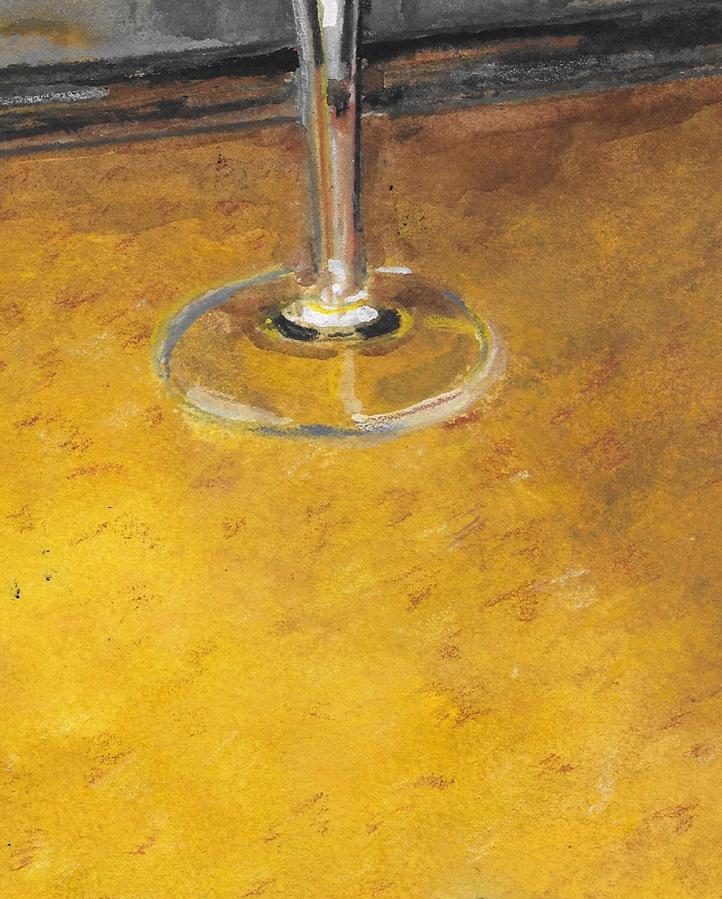

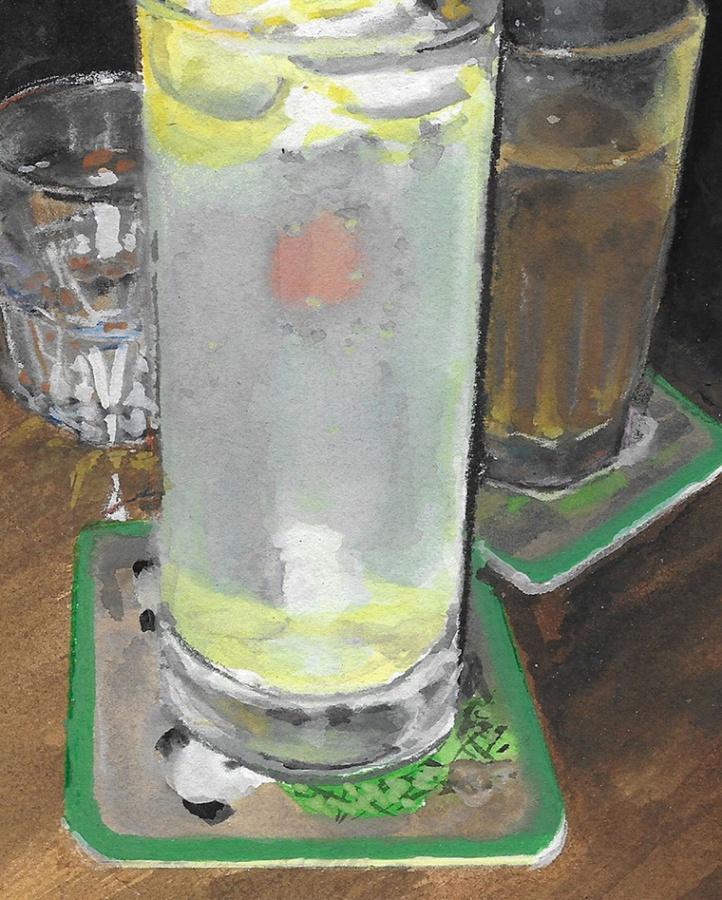

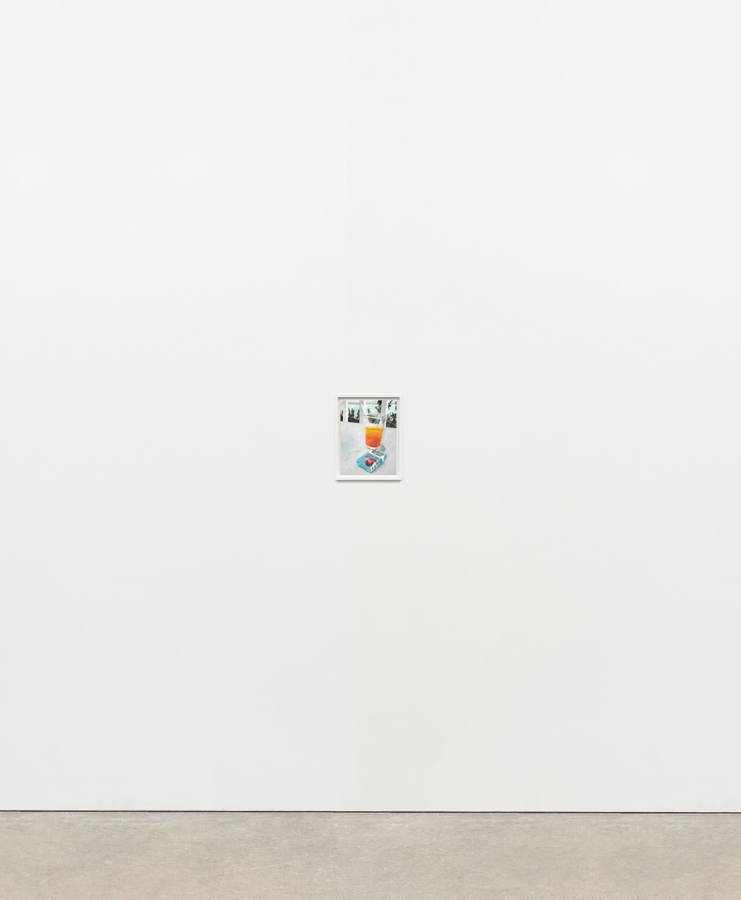

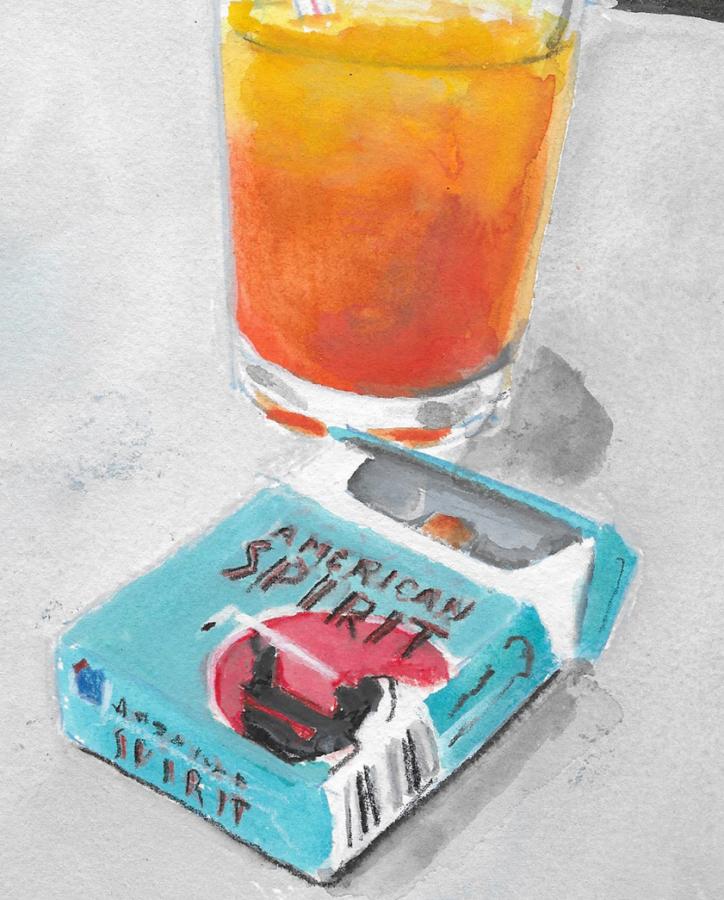

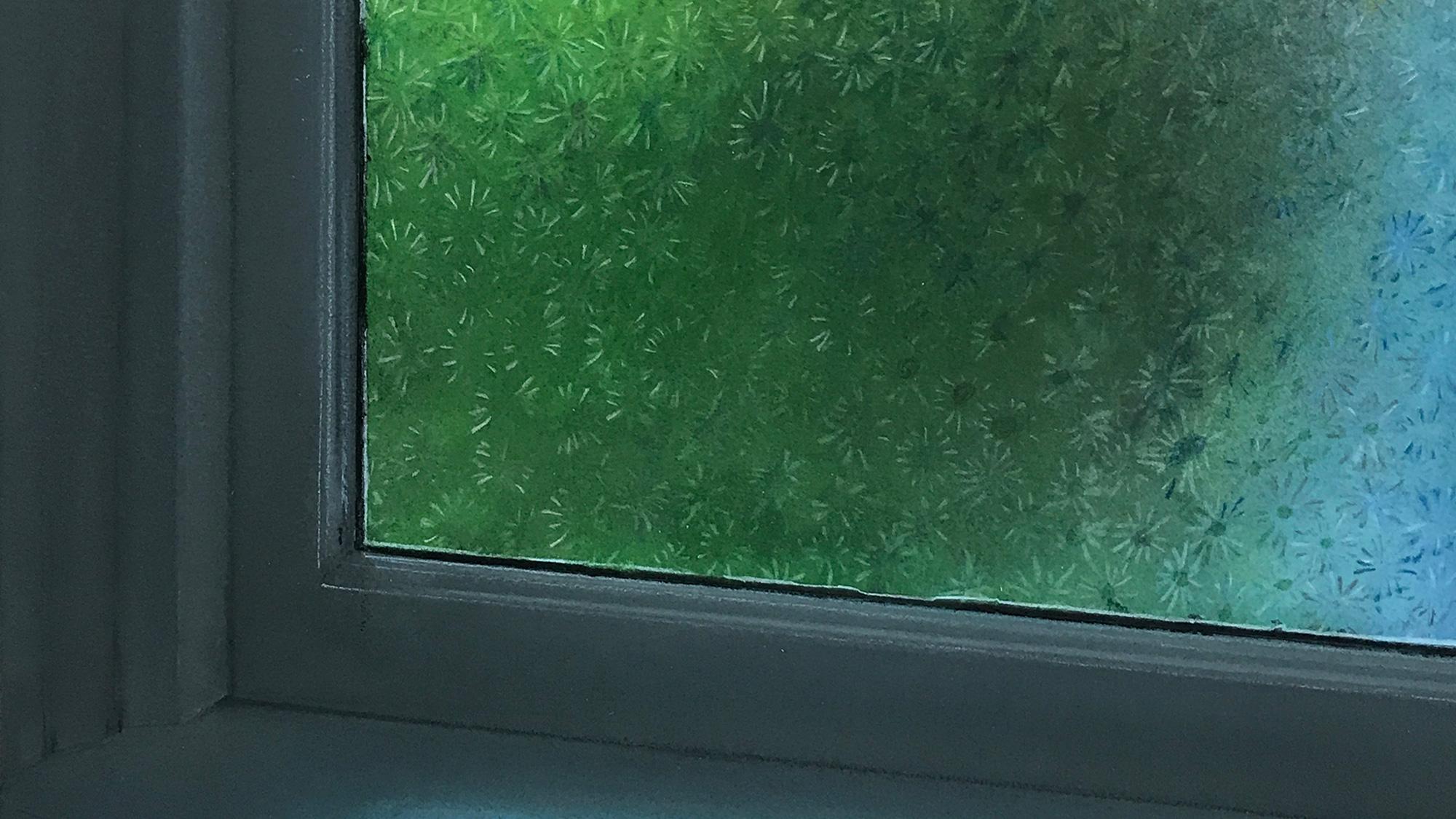

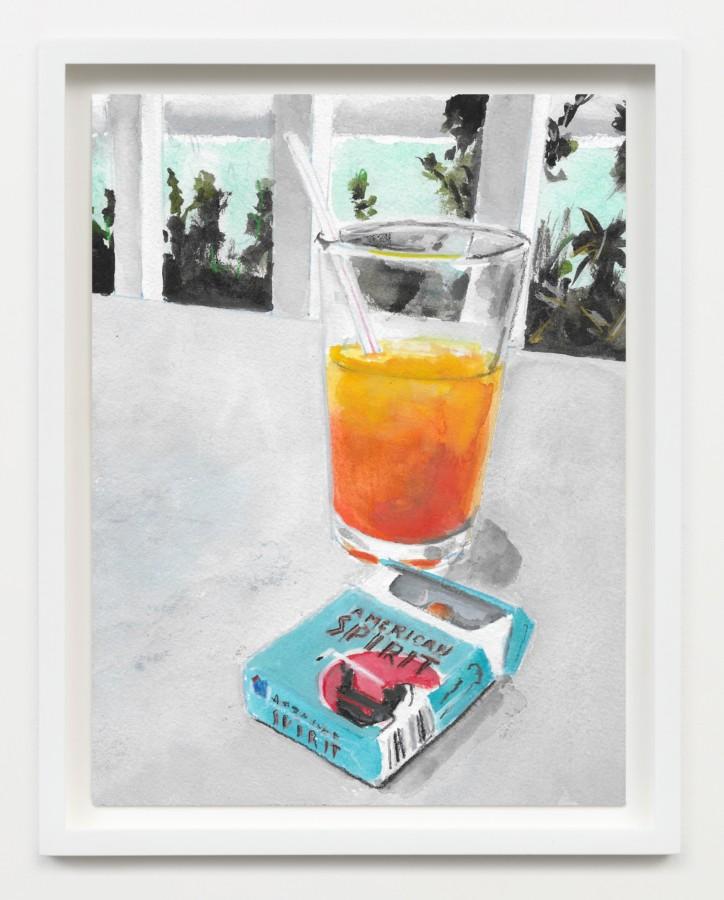

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

8 × 6 inches; 20.32 × 15.24 cm (unframed)

9 1⁄2 × 7 1⁄2 inches; 24.13 × 19.05 cm (framed)

DB-20-017

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

8 × 6 inches; 20.32 × 15.24 cm (unframed)

9 1⁄2 × 7 1⁄2 inches; 24.13 × 19.05 cm (framed)

DB-20-017

Consider a different question: Suppose everything you see as blue I see as yellow, everything you see as pink I see as a sort of teal, and so on. Is there any way that any conversation, no matter how lengthy or detailed, would reveal this fact? Would any brain scan, however exhaustive? You might say, “Well, yellow is hot, and red is angry, and green is soothing.” But I, having lived my life seeing the sun as blue, a man’s face turn green with rage, and my front lawn as bright red, would have no trouble agreeing with you. In the classic case, the same neurons would fire in my head when I looked at the sky as fired in yours: only the experience would be different. This is known as the “reverse spectrum problem”, and its consequences are profound, for if such a thing were possible then sensation would be irreducible to matter, which would leave us forced to endorse a form of dualism, the existence of a mind, even a soul, which exists independently of the brain. This is intolerable to many people; and yet, surely the existence of an undetectable reverse spectrum is possible, if not provable. It is not impossible, anyway, not on the face of it. The concept makes sense. It’s not incoherent. Is it?

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

10 × 7 1⁄2 inches; 25.4 × 19.05 cm (unframed)

11 1⁄2 × 9 inches; 29.21 × 22.86 cm (framed)

DB-20-013

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

10 × 7 1⁄2 inches; 25.4 × 19.05 cm (unframed)

11 1⁄2 × 9 inches; 29.21 × 22.86 cm (framed)

DB-20-013

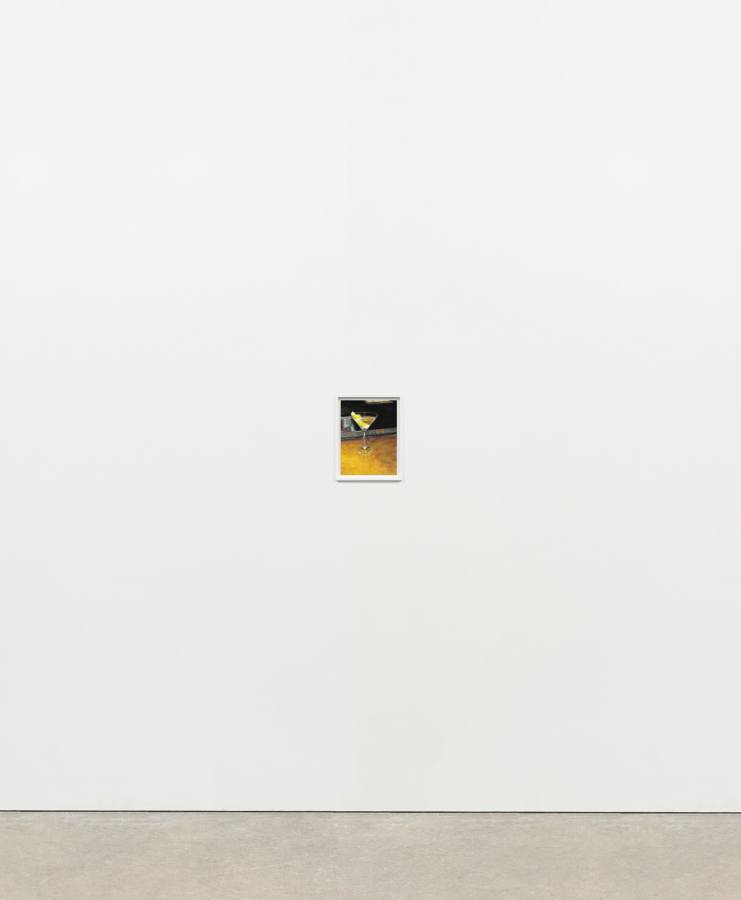

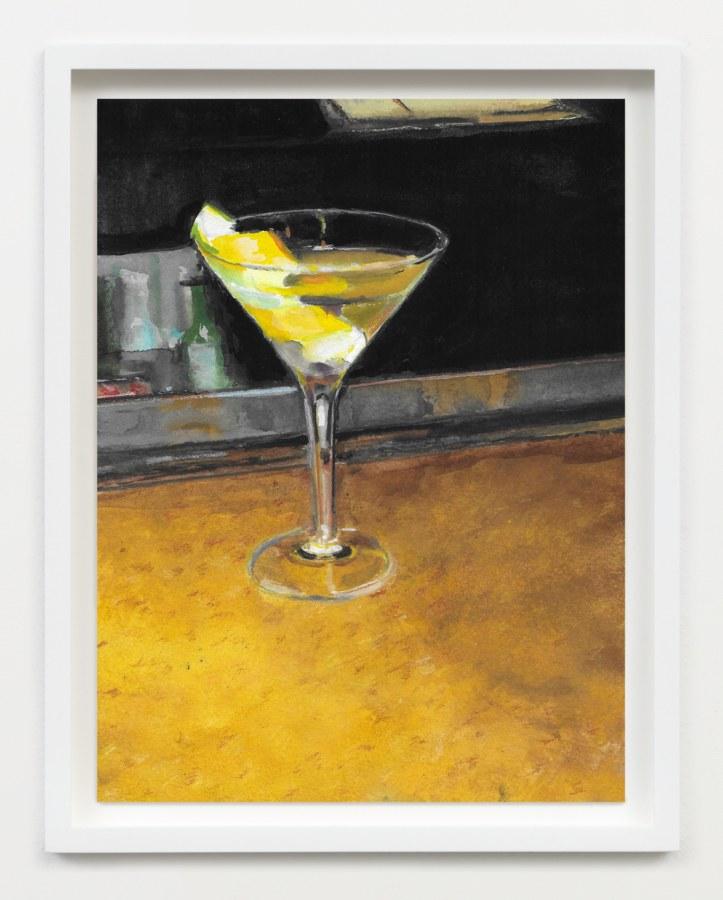

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

10 × 7 1⁄2 inches; 25.4 × 17.78 cm (unframed)

11 1⁄2 × 9 inches; 29.21 × 22.86 cm (framed)

DB-20-016

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

10 × 7 1⁄2 inches; 25.4 × 17.78 cm (unframed)

11 1⁄2 × 9 inches; 29.21 × 22.86 cm (framed)

DB-20-016

Synesthesia is a common enough phenomenon. In an interview, Nabokov says that individual letters provoke in him an irrepressible riot of colors. For example: “V is a kind of pale, transparent pink: I think it’s called, technically, quartz pink: this is one of the closest colors that I can connect with the V. And the N, on the other hand, is a greyish-yellowish oatmeal color.” (Note how he sneaked his initials in there, a very Nabokov thing to do.)

And there is Rimbaud’s immortal “Voyelles”, with its opening lines:

A noir, E blanc, I rouge, U vert, O bleu: voyelles,

Je dirai quelque jour vos naissances latentesA black, E white, I red, U green, O blue: vowels/I shall tell, one day, of your mysterious origins

Other people are known to experience strong associations between, say, musical instruments and smells, or textures and tastes. Human sensation is often just short of insanity.

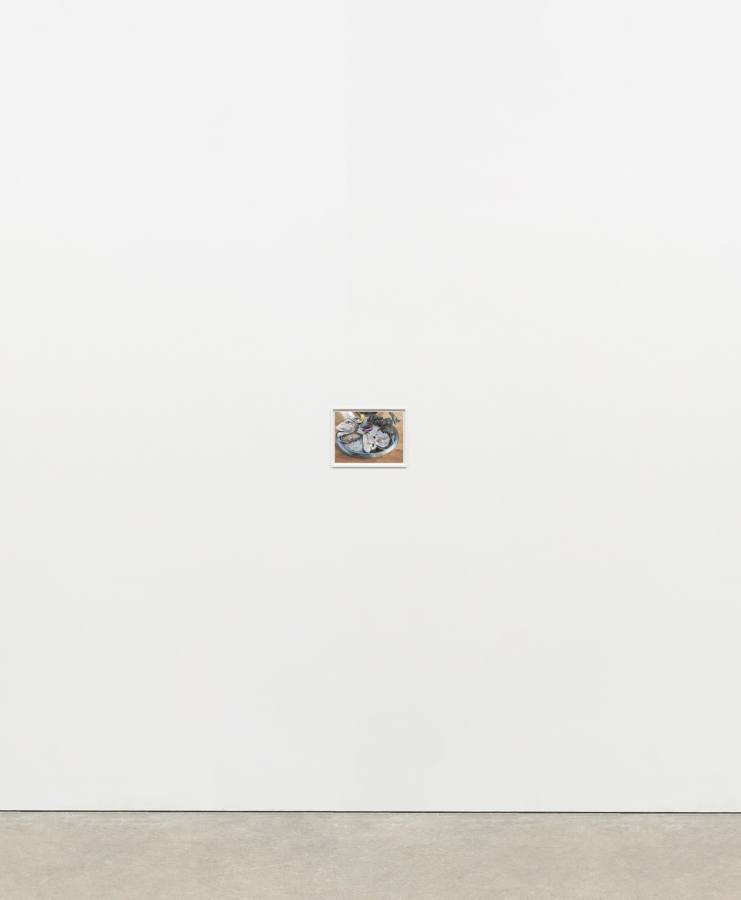

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

7 1⁄2 × 10 inches; 17.78 × 25.4 cm (unframed)

9 × 11 1⁄2 inches; 22.86 × 29.21 cm (framed)

DB-20-019

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

7 1⁄2 × 10 inches; 17.78 × 25.4 cm (unframed)

9 × 11 1⁄2 inches; 22.86 × 29.21 cm (framed)

DB-20-019

In their purest state, both nicotine and alcohol are colorless. Caffeine is white. And while white is not a color, it’s not colorless, either: that is, it’s not transparent. More questions: White can be beautiful, and often is; but can something perfectly transparent be beautiful? Air, for example: isn’t air beautiful – by which I mean, can’t it look beautiful? Can’t a painting of it be beautiful? And yet, how can that be so?

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

10 × 7 1⁄2 inches; 25.4 × 19.05 cm (unframed)

11 1⁄2 × 9 inches; 29.21 × 22.86 cm (framed)

DB-20-021

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

10 × 7 1⁄2 inches; 25.4 × 19.05 cm (unframed)

11 1⁄2 × 9 inches; 29.21 × 22.86 cm (framed)

DB-20-021

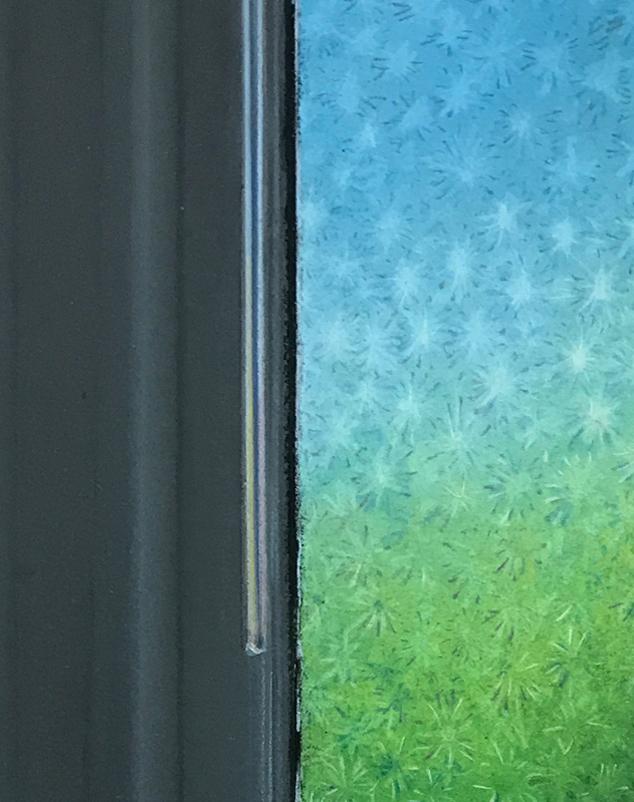

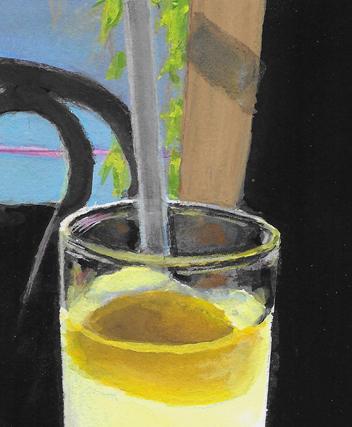

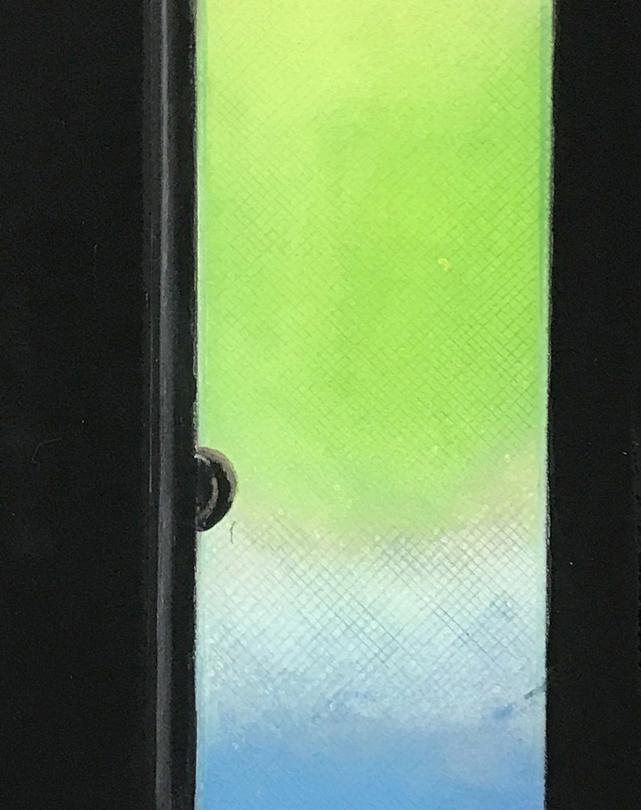

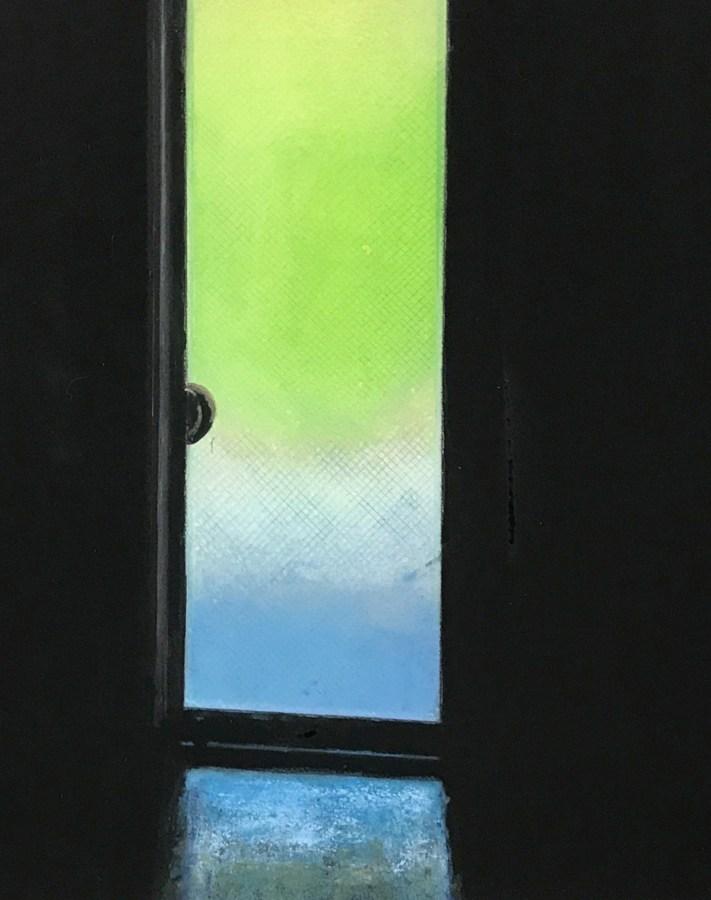

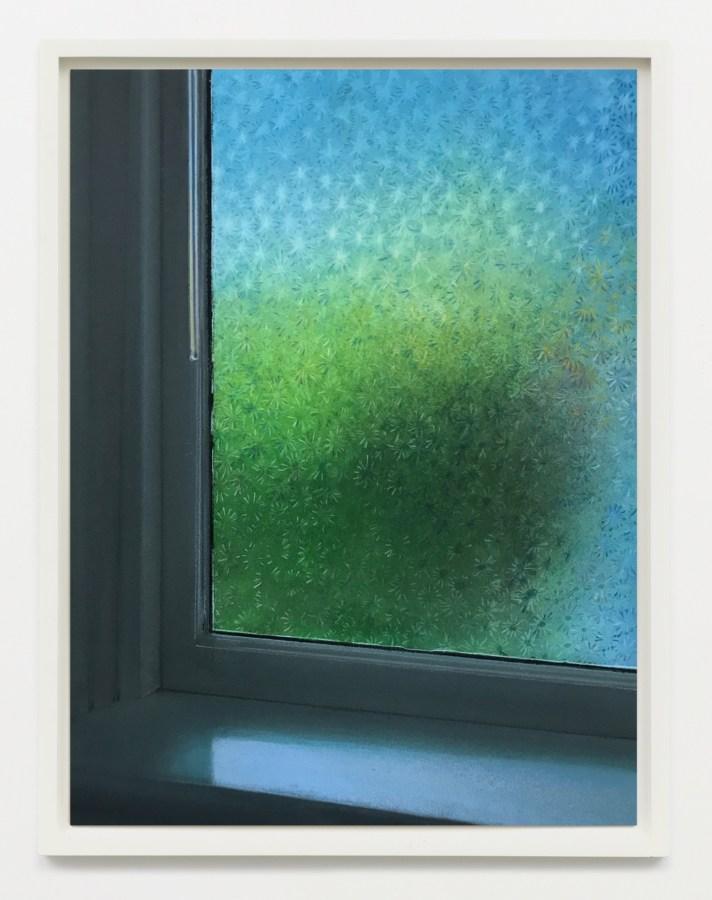

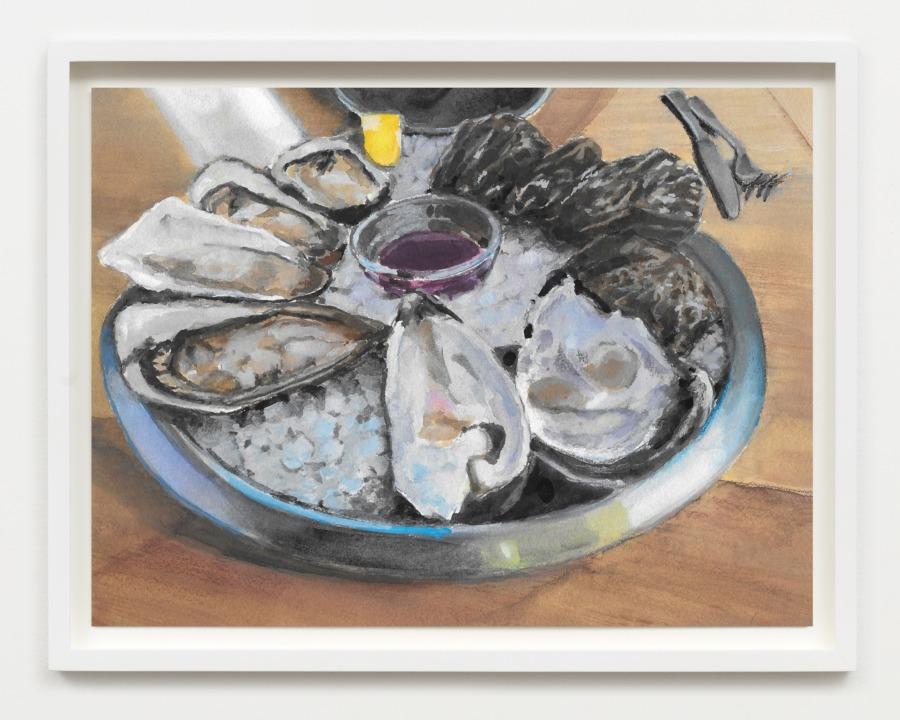

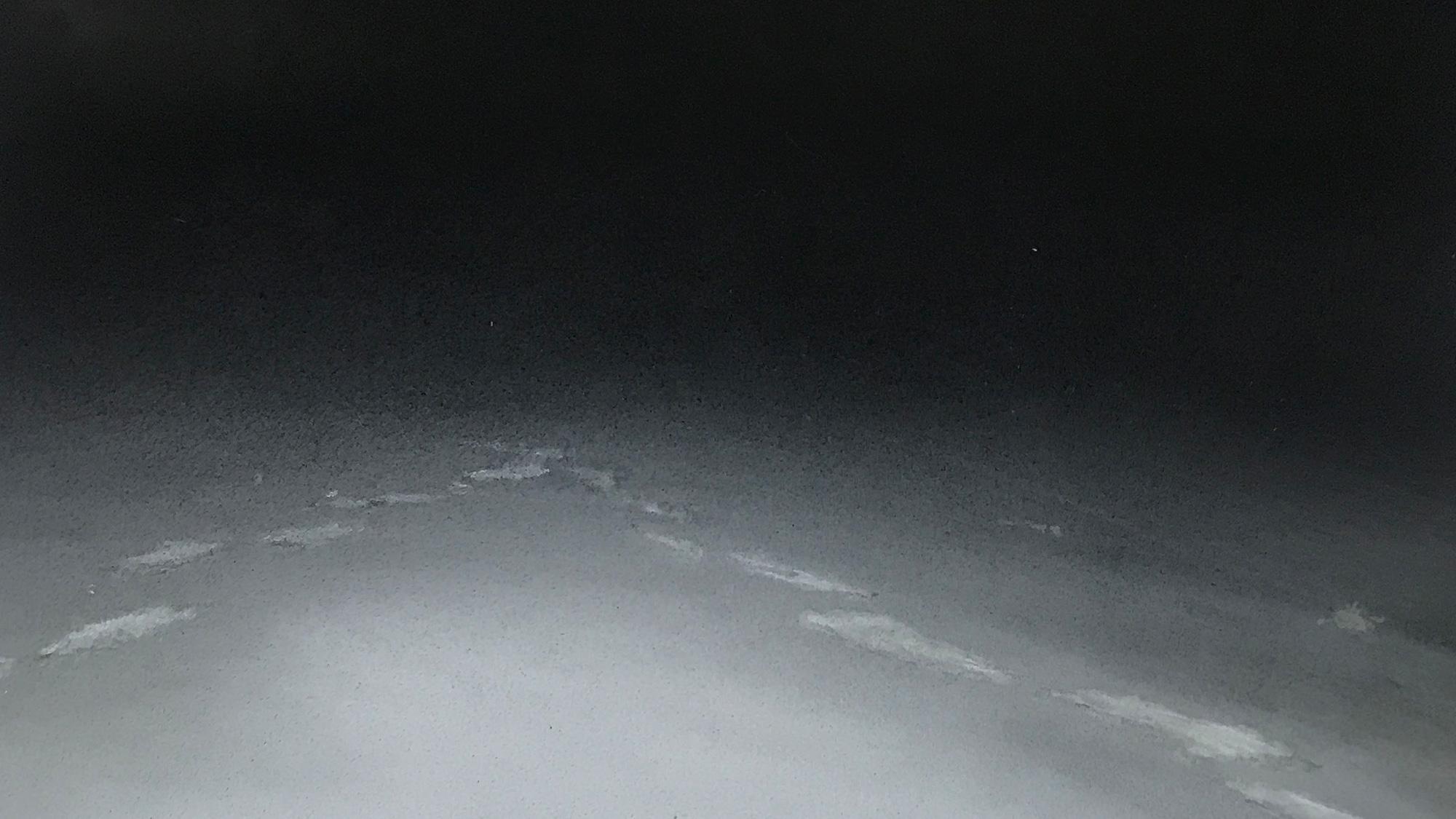

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

20 × 15 inches; 50.8 × 38.1 cm (framed)

21 1⁄2 × 16 1⁄2 inches; 54.61 × 41.91 cm (framed)

DB-20-014

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

20 × 15 inches; 50.8 × 38.1 cm (framed)

21 1⁄2 × 16 1⁄2 inches; 54.61 × 41.91 cm (framed)

DB-20-014

A last inquiry. Where were we when we first saw these things, these particular colors in these particular configurations? Who were we, and who, if anyone, were we with? Why did we want to look at them again? Why do we still want to? How can we convey all this to other people?

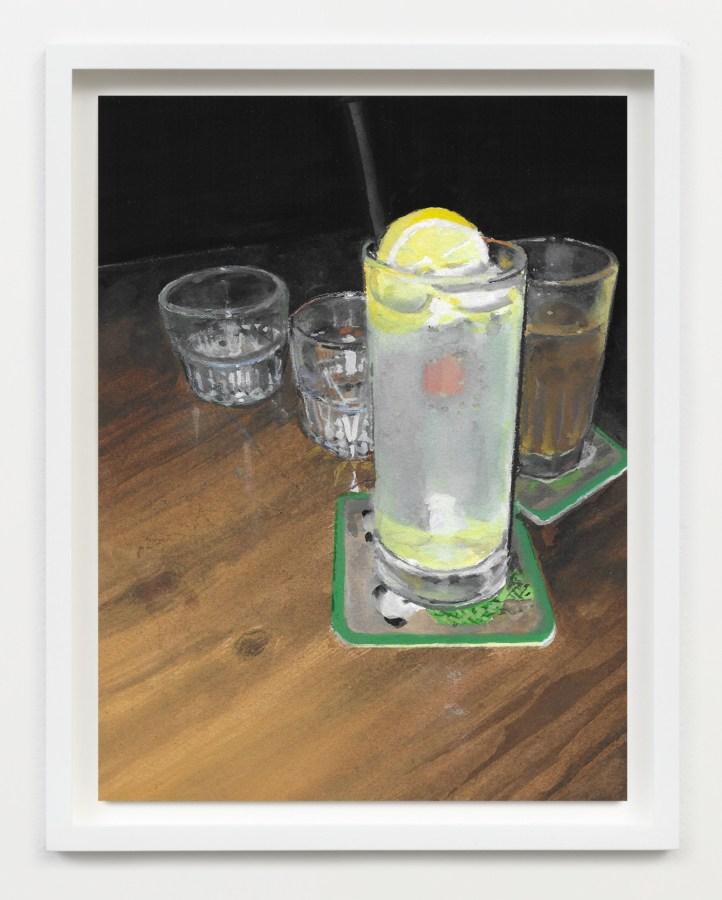

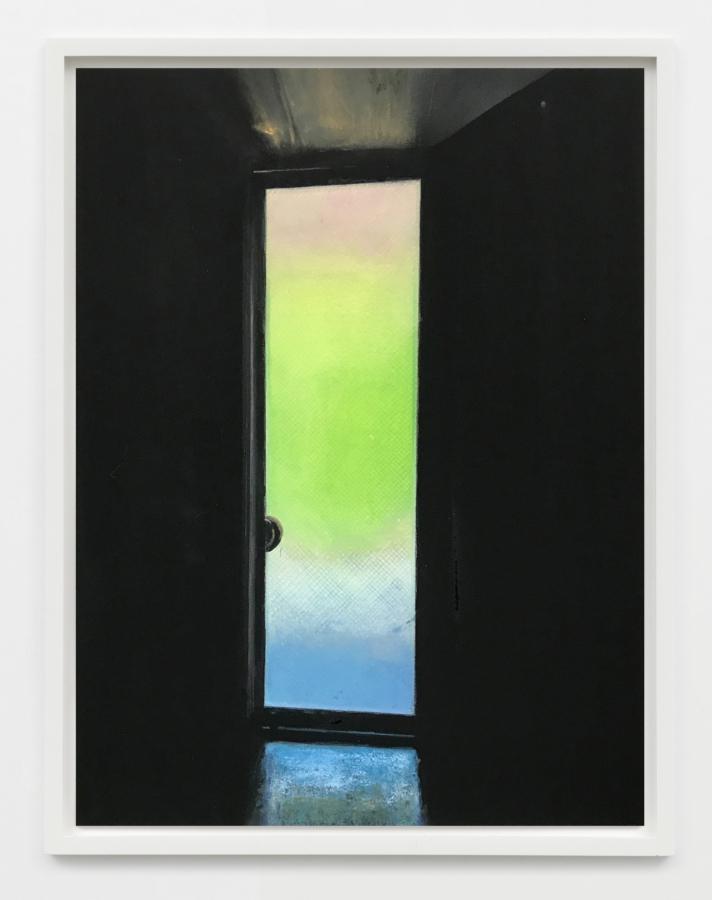

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

24 × 18 inches; 60.96 × 45.72 cm (unframed)

25 1⁄2 × 19 1⁄2 inches; 64.77 × 49.53 cm (framed)

DB-20-015

Dike Blair

Untitled, 2020

Gouache and pencil on paper

24 × 18 inches; 60.96 × 45.72 cm (unframed)

25 1⁄2 × 19 1⁄2 inches; 64.77 × 49.53 cm (framed)

DB-20-015