Before Midnight

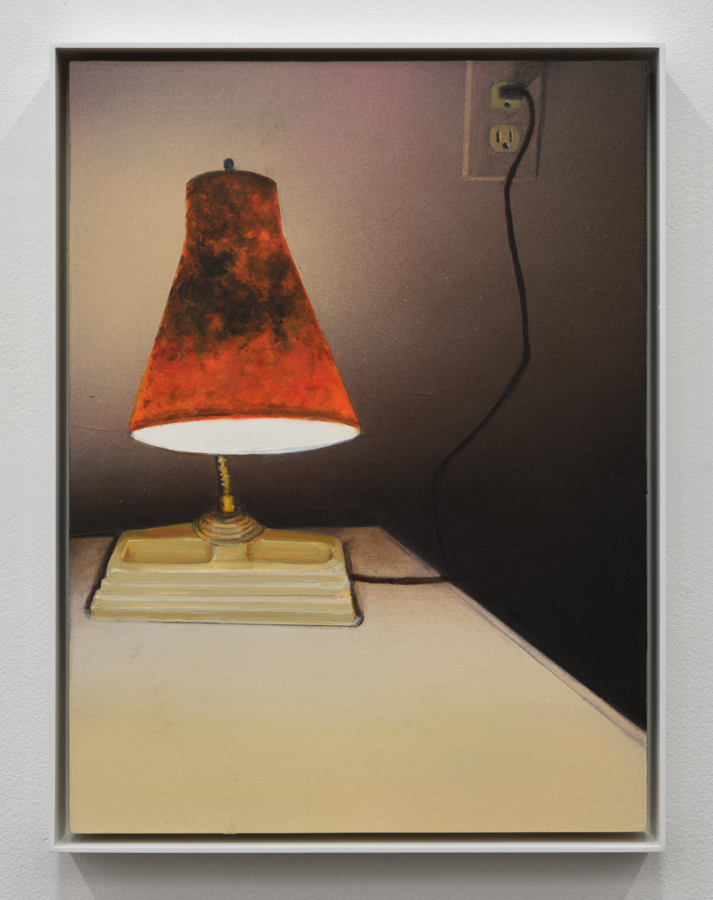

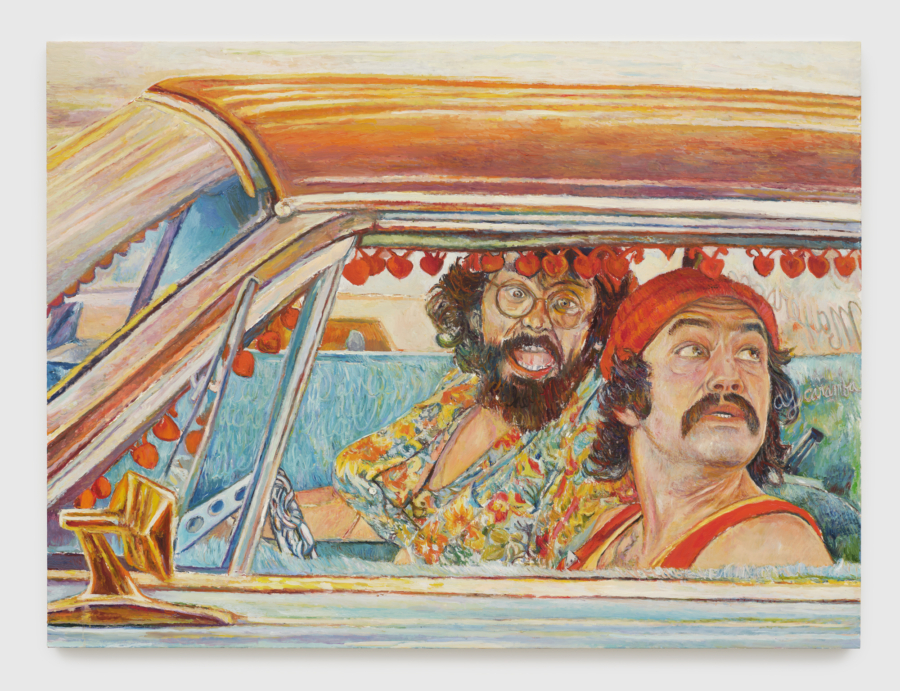

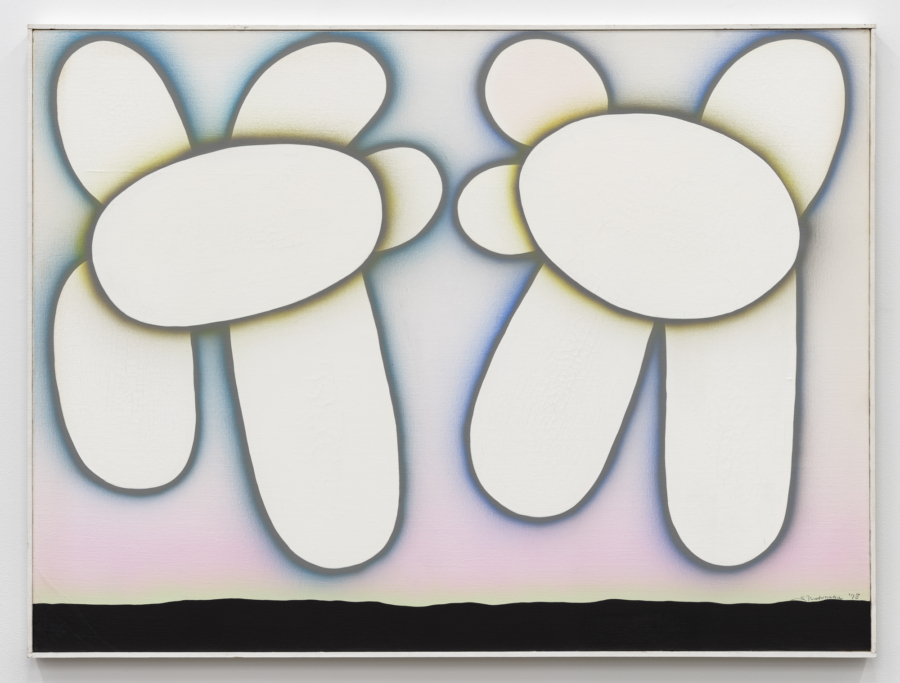

Milton Avery, Forrest Bess, Victor Brauner, Mathew Cerletty,

Ann Craven, Henri Rousseau, Rudolf Stingel

August 13–August 29, 2016

249 Main Street

Amagansett, NY 11937

Before Midnight

Milton Avery, Forrest Bess, Victor Brauner, Mathew Cerletty,

Ann Craven, Henri Rousseau, Rudolf Stingel

August 13–August 29, 2016

249 Main Street

Amagansett, NY 11937

Before Midnight

Milton Avery

Forrest Bess

Victor Brauner

Mathew Cerletty

Ann Craven

Henri Rousseau

Rudolf Stingel

August 13–August 29, 2016

Opening August 13, 6–8pm

In the Louvre there is a work by a primitive painter, known or unknown I cannot say, but whose name will never be representative of an important period in the history of art. This painter is Lucas van den Leyden and in my opinion he makes the four or five centuries of painting that come after him inane and useless. The canvas I speak of is entitled “The Daughters of Lot,” a biblical subject in the style of the period. Of course the Bible in the Middle Ages was not understood in the same way we understand it today, and this canvas is a curious example of the mystic deductions that can be derived from it. Its emotion, in any case, is visible even from a distance; it affects the mind with an almost thunderous visual harmony, intensely active throughout the painting, yet to be gathered from a single glance. Even before you can discern what is going on, you sense something tremendous happening in the painting, and the ear, one would say, is as moved by it as the eye. A drama of high intellectual importance seems massed there like a sudden gathering of clouds which the wind or some much more direct fatality has impelled together to measure their thunderbolts.

The sky of the picture, in fact, is black and swollen; but even before we can tell that the drama was born in the sky, was happening in the sky, the peculiar lighting of the canvas, the jumble of shapes, the impression the whole gives at a distance – everything betokens a kind of drama of nature for which I defy any painter of the Great Periods to give us an equivalent.

A tent is pitched at the sea’s edge, in front of which Lot is sitting, wearing full armor and a handsome red beard, watching his daughters parade up and down as if he were a guest at a prostitutes’ banquet.

And in fact they are strutting about, some as mothers of families, others as amazons, combing their hair and fencing, as if they had never had any other purpose than to charm their father, to be his plaything or his instrument. We are thus presented with the profoundly incestuous character of the old theme which the painter develops here in passionate images. Its profound sexuality is proof that the painter has understood his subject absolutely as a modern man, that is, as we ourselves would understand it: proof that its character of profound but poetic sexuality has escaped him no more than it has eluded us.

On the left of the picture, and a little to the rear, a black tower rises to prodigious heights, supported at its base by a whole system of rocks, plants, zigzagging roads marked with milestones and dotted here and there with houses. And by a happy effect of perspective, one of these roads at a certain point disengages itself from the maze through which it has been creeping, crosses a bridge, and at last receives a ray of that stormy light which brims over between the clouds and showers the region irregularly. The sea in the background of the canvas is extremely high, at the same time extremely calm considering the fiery skein that is boiling up in one corner of the sky.

It happens that when we are watching fireworks, the crackling nocturnal bombardment of shooting stars, sky rockets, and Roman candles may reveal to our eyes in its hallucinatory light certain details of landscape, wrought in relief against the night: trees, towers, mountains, houses, whose lighting and sudden apparition will always remain definitely linked in our minds with the idea of this noisy rending of the darkness. There is no better way of expressing this submission of the different elements of landscape to the fire revealed in the sky of this painting than by saying that even though they possess their own light, they remain in spite of everything related to this sudden fire as dim echoes, living points of reference born from it and placed where they are to permit it to exercise its full destructive force.

There is moreover something frighteningly energetic and troubling in the way the painter depicts this fire, like an element still active and in motion, yet with an immobilized expression. It matters little how this effect is obtained, it is real; it is enough to see the canvas to be convinced of it.

In any case, this fire, which no one will deny produces an impression of intelligence and malice, serves, by its very violence, as a counterbalance in the mind to the heavy material stability of the rest of the painting.

Between the sea and the sky, but towards the right, and on the same level in perspective as the Black Tower, projects a thin spit of land crowned by a monastery in ruins.

This spit of land, so close that it is visible from the shore where Lot’s tent stands, reveals behind it an immense gulf in which an unprecedented naval disaster seems to have occurred. Vessels cut in two and not yet sunk lean upon the sea as upon crutches, strewing everywhere their uprooted masts and spars.

It would be difficult to say why the impression of disaster, which is created by the sight of only one or two ships in pieces, is so complete.

It seems as if the painter possessed certain secrets of linear harmony, certain means of making that harmony affect the brain directly, like a physical agent. In any case this impression of intelligence prevailing in external nature and especially in the manner of its representation is apparent in several other details of the canvas, witness for example the bridge as high as an eight-story house standing out against the sea, across which people are filing, one after another, like Ideas in Plato’s cave.

It would be untrue to claim that the ideas which emerge from this picture are clear. They are however of a grandeur that painting which is merely painting, i.e., all painting for several centuries, has completely abandoned: we are not accustomed to it.

— excerpt from Antonin Artaud, “Metaphysics and the Mise en Scène” in The Theater and Its Double, 1938

The three exhibitions Before Sunrise, Before Sunset, and Before Midnight explore our continually transforming relationship to landscape. The works range from precisely-rendered picturesque scenes, to distorted surreal realms with far-out arrangements, to reductive abstract representations of nature.