Louise Fishman

Ballin’ the Jack

November 5–December 20, 2020

188 E 2nd St & 172 E 2nd St

New York, NY 10009

Louise Fishman

Ballin’ the Jack

November 5–December 20, 2020

188 E 2nd St & 172 E 2nd St

New York, NY 10009

Derived from an early-twentieth-century, vernacular expression, “ballin’ the jack” means going very fast or doing something very quickly. Such connotations are mirrored in the lateral, tilting swipes and diagonal bursts of black, grays, and greens that traverse the open expanse and anchor the energized field at its edges. “Ballin’ the jack,” though, can also be a gambling expression used to describe risking it all in one go. Going all-in. An apt description, too, of Fishman’s approach to painting.

—Debra Singer, “Going Rogue”

Karma is pleased to present Ballin’ the Jack, a solo exhibition by Louise Fishman. The exhibition consists of two new bodies of work: oil paintings created in her studio in New York City and watercolors made at her home upstate.

The exhibition celebrates the athletic fervor and genre-bending accomplishments of Fishman’s practice. Beginning her practice at the height of Abstract Expressionism, Fishman asserted herself as a queer feminist Jewish woman within the artistic milieu of the time. Her calligraphic mark-making, atmospheric spaces, and muscular articulations recount the urgency of her self-expression, and speak to the sentiment of “ballin’ the jack.” After relocating to upstate New York this spring, Fishman’s work drew influence from her new pastoral setting. Energized by the change, her small-scale watercolors celebrate the beauty of the countryside and display a refreshing poetic sensibility. Ballin’ the Jack charts a before and after: a material record of this shift in the artist’s vision.

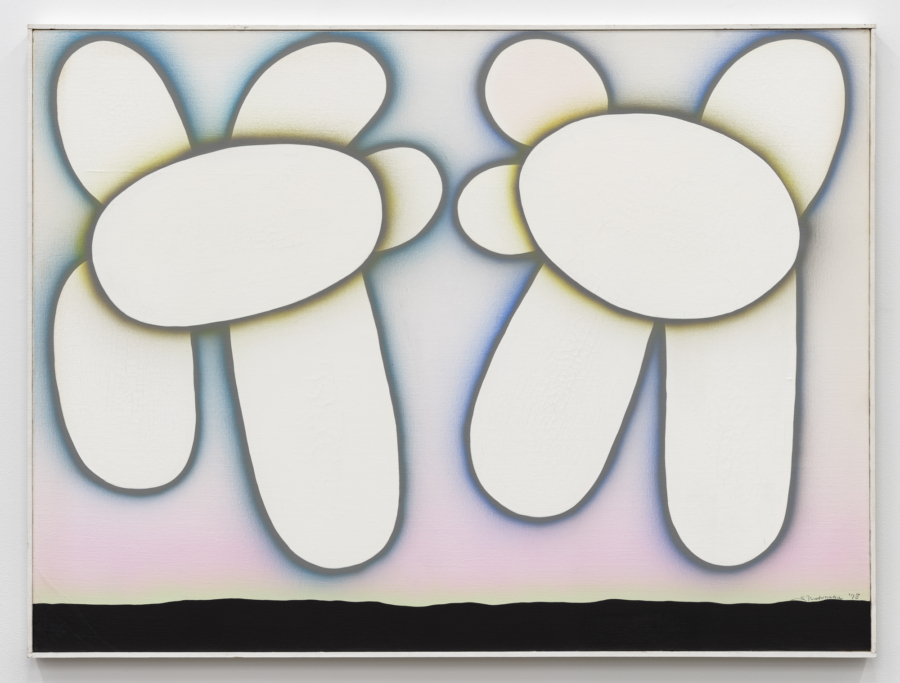

Fishman’s paintings fuse gestural abstraction with geometric minimalism, often featuring her hallmark grid motif. Unlike the grids of Mondrian and LeWitt, Fishman’s are sculptural, yet evanescent—at times overt and at others subtle. Rigid rectangles of paint give way to airy hash marks, which fade into the background as Fishman reworks the surface. Fishman has referred to her compositions as a “breathing system,” underscoring the influence of meditation on her practice.

While these abstractions do not chronicle Fishman’s life, their production is informed by her private, political, and cultural encounters. The works are infused with the literature, music, emotions, and philosophies that move her. Choral Fantasy is titled after the Beethoven composition playing while Fishman was working; Unbinding refers to the Vipassana Buddhist notion of “unbinding” the mind; A La Recherche was doubly inspired by her mother’s favorite writer and by a Proustian play she attended.

The artist utilizes the robust gestures of Abstract Expressionism not in spite of its masculine roots, but, in part, because of them. Through paintings such as Mondrian’s Grave, Fishman subverts what Helen Molesworth has called the “field of gendered language” that has often been used to historicize abstraction. Splatters, sfumato, impasto, and scratches—Fishman’s canvases are troweled, scraped, and peeled, exuding a forceful physicality. The visual language of Dugout testifies to the strenuous activity behind Fishman’s creations; heavy blends of oil paint, skims of color, and jagged textures are interwoven with raucous cacophony. Its layering of textures produces a recessive, spatial quality. The surface is broken into a multitude of planes: flat blocks of muted greens, browns, and reds are thickly laid down with the edge of a palette knife. Blurs and scratches record horizontal movement: the activity of a sweeping hand. As Suzan Frecon writes, “One can perhaps think of musical dimensions while trying to describe [Fishman’s works], from very loud, smashing crescendos, to the whisper finesse of a dribble or caress of paint, directly from her mind-passion-hand, applied with varied and unorthodox painting tools such as trowels, various painting knives, and many common implements found in hardware stores and on NYC’s old Canal Street.”

The sweeping views of Fishman’s upstate setting inspired a new, bucolic vernacular. Her lyrical small-scale watercolor paintings reflect this agrestic change of scenery. Earthen tones, fluid and stippled marks—all evoke the colors and surface characteristics of soil, rocks, trees, and flowers. Aerated, ethereal blue washes allude to country brooks and streams; flecks of red and green slashes echo floral imagery. Fishman’s atmospheric brushwork is effervescent and vivacious. Unrelentingly emotive, the collected paintings of Ballin’ the Jack evoke Fishman’s energetic, compassionate vision.

The exhibition is accompanied by a definitive, comprehensive monograph of around 500 works spanning from the 1950s to the present day. The publication archives the development of the artist’s visual vernacular, and includes narratives by Suzan Frecon, Bertha Harris, Aruna D’Souza, Andrew Suggs, John Yau, an essay published by the artist, and two newly commissioned texts from Debra Singer and Josephine Halvorson.