April 10, 2025

Well before artificial intelligence images flooded our lives, more straightforward photographs, film and videos amassed at their own fevered clip. Not long after the technical innovations that made them possible, there were so many images that we didn’t know what to do with them.

Artists and thinkers like Aby Warburg, Andre Malraux, Frank Mouris, Harun Farocki and Camille Henrot examined and cataloged images. Mungo Thomson has developed his own system, rephotographing images in vintage instructional manuals, nature guides and art history textbooks. These are presented in rapid-fire succession as stop-motion animation videos — essentially animating Eadweard Muybridge’s 19th-century still images of human and animal “locomotion” — and accompanied with mostly experimental soundtracks.

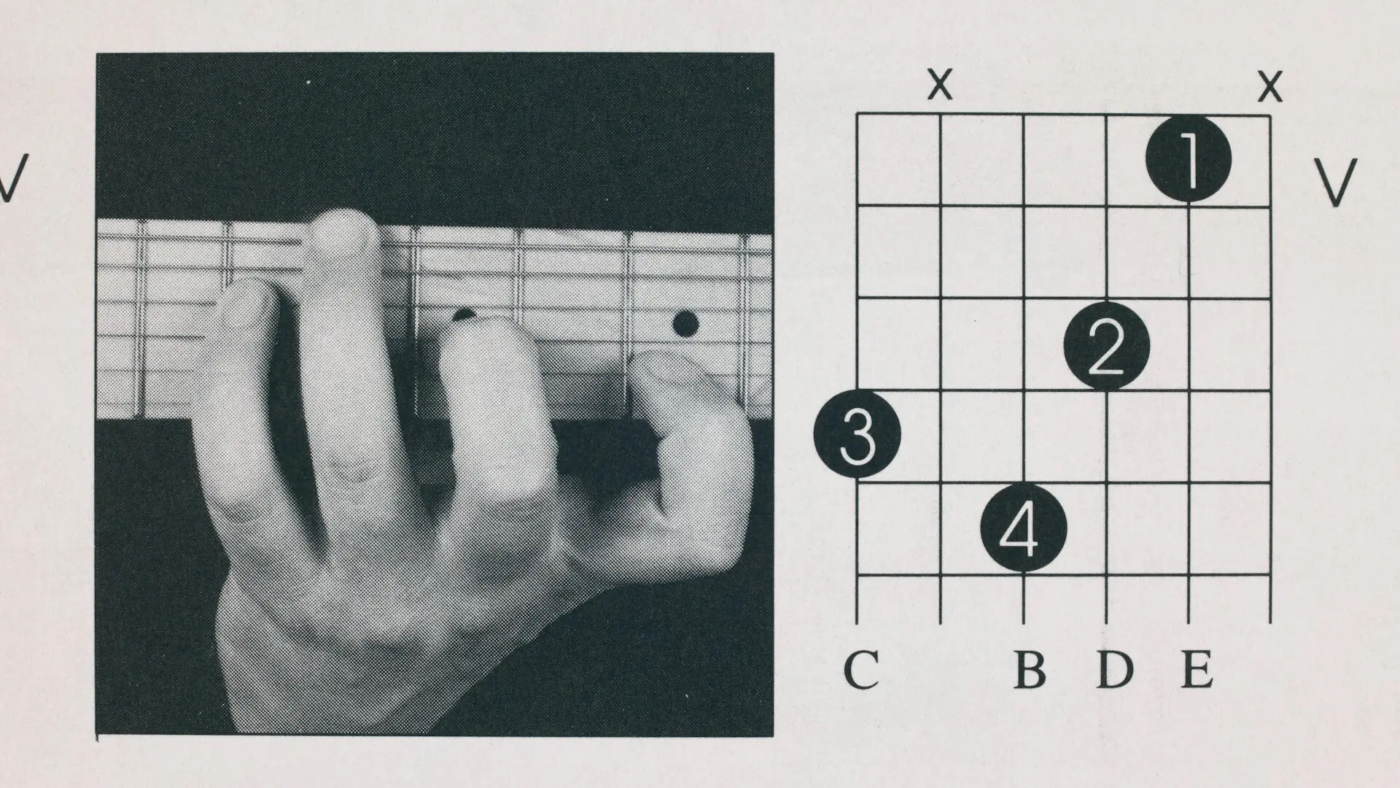

“A Universal Vision,” spread over two Karma locations, is a stellar collection of these videos. Here are images from guides to hummingbirds and seashells, instruction manuals for playing guitar and throwing pottery on the wheel, and art history books. Accompanying the images are sounds and scores by John McEntire, Eiko Ishibashi, Lee Ranaldo, Mark Fell and Will Guthrie, as well as György Ligeti’s 1962 “Poème Symphonique.” The flicker effect of the images and expertly synced sound is oddly relaxing — the opposite of doom-scrolling.

Down the street in another gallery, nearly blank covers of Time magazine, with their distinctive red border, are silk-screened onto a series of mirrors (Time being, of course, one of the biggest purveyors of photographs before the internet). Stand in the middle of the room, between the mirrors, and your image is reflected to infinity.

With this work, the show’s title becomes clear: “Universal vision” is a farce. Every single photo ever made is programmed by an apparatus and replete with ideology. Therefore, if billions of images are uploaded to social media (alone) every day, Thomson’s exercise in painstakingly recuperating, rephotographing and recirculating a few thousand images helps explain, in part, why the world feels so crazy these days. We’re drowning in images.